Blue Velvet is an astonishing movie, certainly for its amazing characters and images, its striking color palette, and its action that goes totally over the top. But Blue Velvet is also amazing because it succeeds in being both traditional and postmodern at the same time.

Traditionally, American films have been concerned with good and evil far more than the movies of Europeans or other nationalities. Think of the distinctly American genres like the western, the gangster film, or film noir. Think of the time-honored, treacly favorites like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Miracle on 34th Street, the Andy Hardy movies, Hallmark cards, Norman Rockwell, and on and on. Think of the adventure films like the Indiana Jones, Terminator, or Batman franchises. Let’s face it. We Americans approach things moralistically.

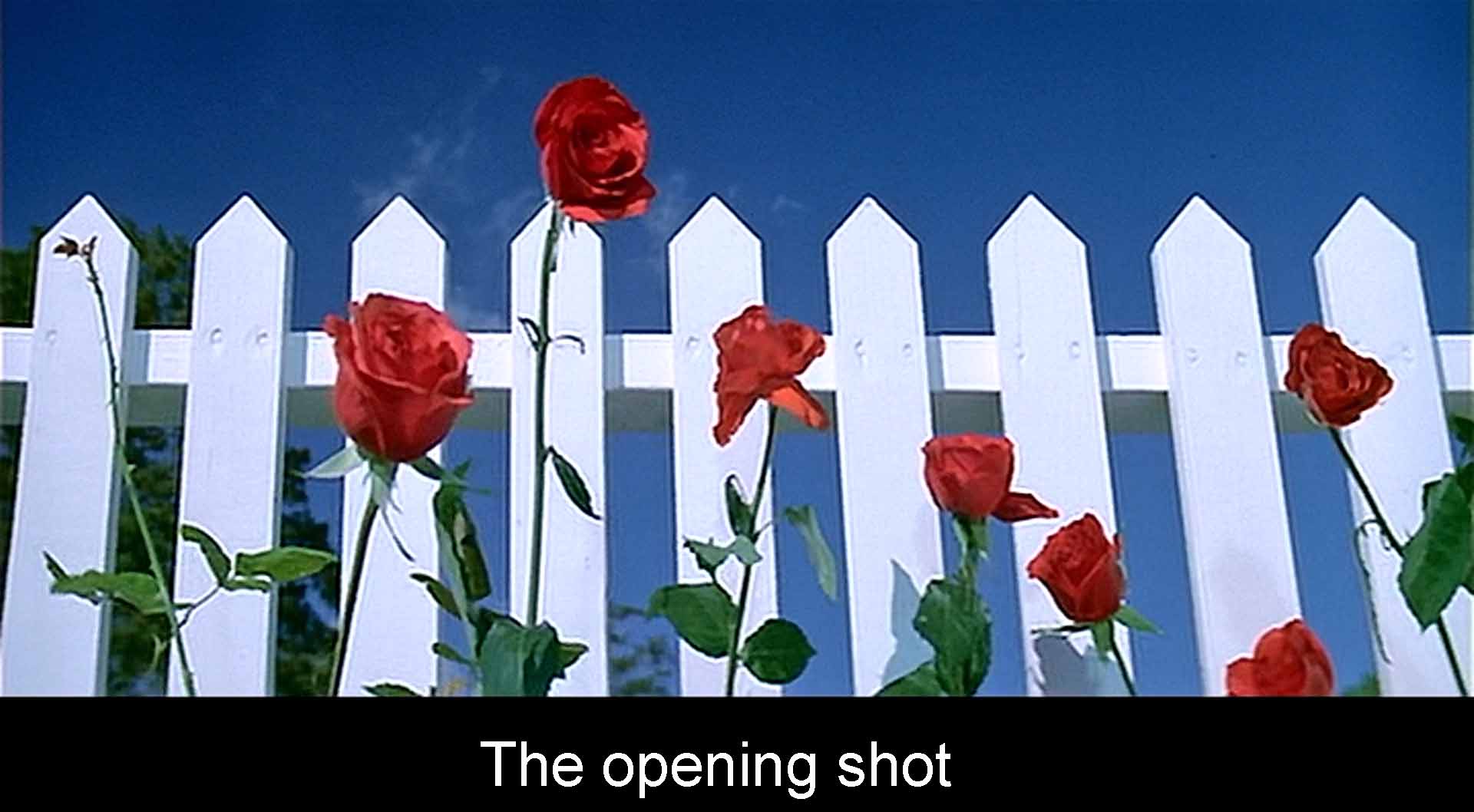

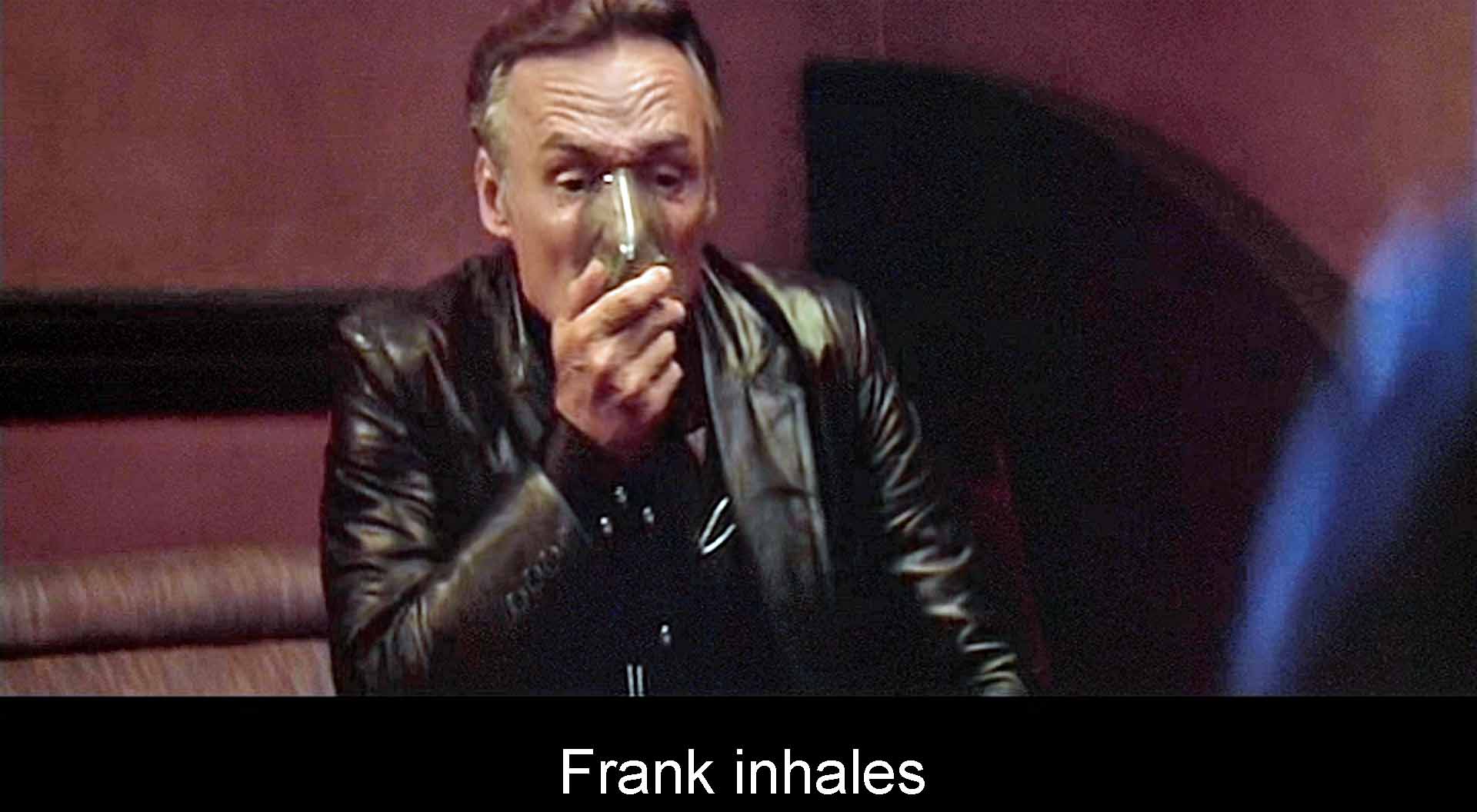

The film opens with sentimental pictures of Lumberton, an Eisenhoverian all-American Small Town. Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle Maclachlan) is home from college to tend his hospitalized father. Then he finds an ear. He takes it to police Lt. Williams, a neighbor (George Dickerson), who tells him to keep out of it. But Jeffrey gets the lieutenant’s daughter Sandy (Laura Dern) to help him investigate on his own. Jeffrey learns that Dorothy, sexy singer of “Blue Velvet” (Isabella Rossellini) is involved somehow. He hides in Dorothy’s apt, where he sees her having some weird sexual game with brutal, drug-sniffing, blue-velvet-fixated weirdo, Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper). Jeffrey learns that Frank has kidnapped Dorothy’s husband and child and so forces her to be his sex slave. Frank captures Jeffrey, shows him off to his “suave” drug dealer Ben (Dean Stockwell), torments Dorothy and Jeffrey, and finally beats Jeffrey brutally. Eventually the police raid Frank’s hideout, and Jeffrey kills Frank in a shoot-out. We settle into a Hallmark-cards happy ending that recapitulates the sentimental shots of the opening. Notice that, in keeping with the shmaltzy opening, Blue Velvet builds on a Hardy Boys or Nancy Drew plot: a good teenager risks himself to solve a crime, expose evil, and bring the nasties to justice.

Blue Velvet begins with the lily-white small town of America’s collective fantasies and shows us its dark underside: drugs, violence, sex, and particularly sexual perversion. Our hero, Jeffrey, hiding in the dark, peers through the slats of Dorothy Vallens’ closet at Dorothy getting undressed and Frank’s strange sadomasochistic sex with her. Jeffrey stands for all of us American filmgoers peering (voyeuristically!) at Evil in traditional American films. Lynch clues us as to how we should read his film when he shows us a cluster of ants under the Beaumonts’ pretty lawn. This is Tennyson’s nature red in tooth and claw—the underside of cutesy Lumberton with its free enterprise propensity for cutting down trees.

In Jeffrey, Frank, Ben, and Dorothy, Lynch has created a weirdly oedipal version of a family—so suggests Thomas Caldwell. That is, Frank is the brutal and dangerous father to Jeffrey and a sexually abusing husband to Dorothy. Ben is like a sibling preferred to Jeffrey. Lynch has replaced Dorothy’s real family, her husband Don and son, with what Laura Mulvey calls a “netherworld.”

Lynch has said that he gets his ideas after working up a caffeine and sugar high in a local hamburger joint. He makes movies erratically, even randomly with the result that there are a lot of odds and ends in them. I’m the kind of critic who wonders, what are they doing there? How do they fit together to make a consistent work of art? Many critics today would say that’s not a question to ask. That’s imposing your ideas of art on the artist. I could reply that I’m trying to give the artist as much expression as I can.

So I still ask, why are these things there? I call these oddments my why’s. Why an ear, anyway? Why the blind and sighted black clerks in the Beaumont hardware store? Why the red drapery ominously but improbably bulging in Dorothy’s apartment? Why Dorothy’s implausible lipstick and wig? If you want to read my efforts at integrating these why’s click here.

These days few other critics ask about the why’s. Most have read Blue Velvet moralistically, in the American tradition. Picket-fenced, red-rosed, squeaky-clean Lumberton is Good with a capital G. And of course the teen detectives Jeffrey and Sandy are Good. Frank and his gang and his chum Ben are Evil with a capital E. Evil is the underside of Good. It’s a simple reading, not to say simplistic.

Blue Velvet is traditional and very “American,” but David Lynch is also a practicing postmodernist. I should explain what I mean by that trickily overused term. In my thinking, modernism creates works of art that depart from traditional links to reality and convention. Modernist works stood on their own: cubist Picasso paintings, abstract Calder sculptures, atonal music, novels like Ulysses or The Sound and the Fury, or such film genres as the western, the gangster film, the remarriage comedies, Hitchcock. These films purported to render reality—that’s what cameras do, after all—but in fact presented highly stylized worlds, worlds as stylized as cubism.

Along came postmodernism, after and beyond modernism. Instead of creating a free-standing work of art, the artist works with your and my reactions to what has been created. The most obvious example is conceptual art where a work of sculpture consists of the directions for making the sculpture instead of the sculpture itself. But think, too, of John Cage’s 4’33”, Andy Warhol’s prints, Roy Lichtenstein’s comic-book pop art, or the monotonies of Philip Glass’ or Steve Reich’s music. In film we have—David Lynch.

All draw on what you bring to the work of art and how you react. That’s why postmodernists thrive on “appropriating” earlier works or conventions and parodying or “interrogating” them, particularly for issues of political and cultural power. In film this translates to working with your semi-conscious knowledge of earlier film genres and conventions that convince us of conservative values, here, the highly conventional presentation of pretty little Eisenhoverian Lumberton. Lynch plays with your expectations built on the Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, Hallmark cards, Andy Hardy, film noir, and Norman Rockwell, all of which express a lily-white, middle-class dominance along with sexual inhibition. And as a postmodernist he will turn your expectations upside down and inside out. He will violate your sensibilities. Hence the over-the-top sex, violence, and profanity of Blue Velvet.

Suppose I said, “This is certainly a movie you want to take the children to” You’d understand that I mean exactly the opposite, that this is very much not a movie you’d take the children to. That’s irony, and it’s a cardinal tactic postmodern artists use all the time. Irony’s a way to create art based on your negative response.

In Blue Velvet, it’s pretty clear that we are to view the opening images of Lumberton ironically. Those roses and tulips are hard to believe, and why are the firemen on the firetruck (complete with Dalmatian!) waving? Then there are the ants in the grass beside collapsed Mr. Beaumont—the underworld beneath the pretty lawns. There is the radio announcer cheerily urging his audience to go out and chop down more trees. There are the nicey-nice teenagers, Jeffrey and Sandy. Lynch has made all of them deliberately unbelievable.

By the same token, though, I believe we are to understand the images in Frank Booth’s world ironically. This evil is as exaggerated as the picket fence and roses with which the picture opens. (And here I’m following a fine article by Paul Coughlin.)

When you exaggerate, the effect is parody or satire, and they are what Lynch does. What was evil in most films of the '50s and '60s? Corrupt politicians, greedy capitalists, criminal bosses, or your basic thugs and murderers. Nothing like Frank Booth, dragging on amyl nitrite, indulging in weird sex, weeping at pop tunes, stuffing pieces of blue velvet in his mouth. Frank is unbelievable (except maybe in Carl Hiaasen’s South Florida). “Frank,” writes Coughlin, “is Lynch’s most potent weapon in his battle against frameworks which work to limit exposure to the unknowable. These are the frameworks that implicitly declare that perversity, absurdity, and irrational excess do not even exist.”

The Evil penetrates the Good. Jeffrey becomes complicit in Frank’s evil, first by his unseemly curiosity, then as a voyeur peeping at nude Dorothy, then Frank and Dorothy’s sexual games, and finally when he is himself seduced by Dorothy. He even joins in her sadomasochism, “Hit me!” And he enjoys it. In the finale, this all gets cleaned up. We have Frank’s clean ear instead of the rotting ear in the vacant lot. The robin from Sandy’s idealistic dream of universal love—a hope of Lynch’s, by the way—kills the ants. Sure, but it’s an artificial robin, a Disney animatronic. Fake. Not to be believed, any more than this ending is to be believed or Frank Booth or Dorothy or Ben or Jeffrey and Sandy.

Viewers will disbelieve, maybe laugh at the excess. David Lynch’s cinema is a cinema of exaggeration. When you see Blue Velvet, then, be alert to moments of exaggeration not just in the pretty daylit world of Lumberton, but in dark nighttime Lumberton as well.

In sum, Blue Velvet isn’t just about good and evil. It’s a radical critique of traditional, particularly conservative, notions of good and evil and, beyond even that, the idea that you and I can know good and evil. The point of Blue Velvet is that you don’t know and maybe you can’t know what real good and real evil are. Our traditional films and media don’t give us a visual vocabulary for knowing—except, of course, for the vocabulary of Blue Velvet. The last word belongs to David Lynch: “[O]nce you’ve discovered there are heroin addicts in the world and they’re murdering people to get money, can you be happy? It’s a tricky question. Real ignorance is bliss. That’s what Blue Velvet is about.”

Items I’ve relied on:

Caldwell, Thomas. “David Lynch.” Senses of Cinema: Best Directors. http://sensesofcinema.com/2002/great-directors/lynch/. Accessed Aug. 12, 2012.

Coughlin, Paul. “Blue Velvet: Postmodern Parody and the Subversion of Conservative Frameworks.” Literature/Film Quarterly, 31. 4 (2003): 304-311.

Mulvey, Laura (1996). “Netherworlds and the Unconscious: Oedipus and Blue Velvet”, Fetishism and Curiosity. London: British Film Institute. 137-154.