I see lots of why’s in Blue Velvet and, indeed, in all of David Lynch’s films. It’s his style. Maybe I shouldn’t expect answers, but it’s my nature: I expect the different elements of a film to fit together in some coherent way. For example . . .

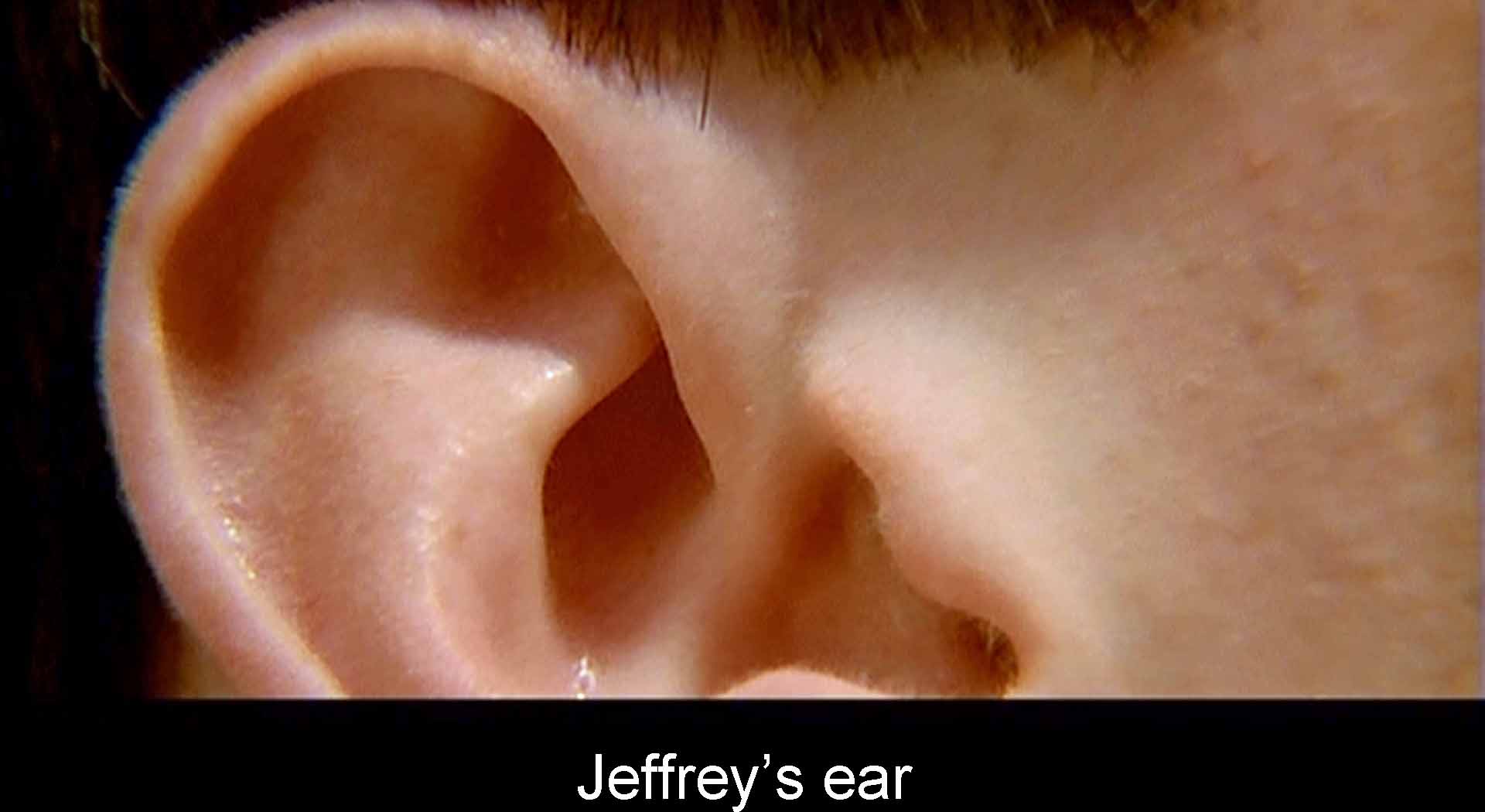

Why an ear? Sound matters all through this movie, for example, Dorothy Vallens’s singing (or Ben’s lip-syncing), Sandy’s four honks of the car horn, or the business with the police radios in the final shoot-out. Lynch worked intensely with Angelo Badalamenti on the music in this and his other films. The rotting ear, a sign of Evil, is matched by Jeffrey’s ear in the finale, a sign of Good that returns us to the Norman Rockwell world.

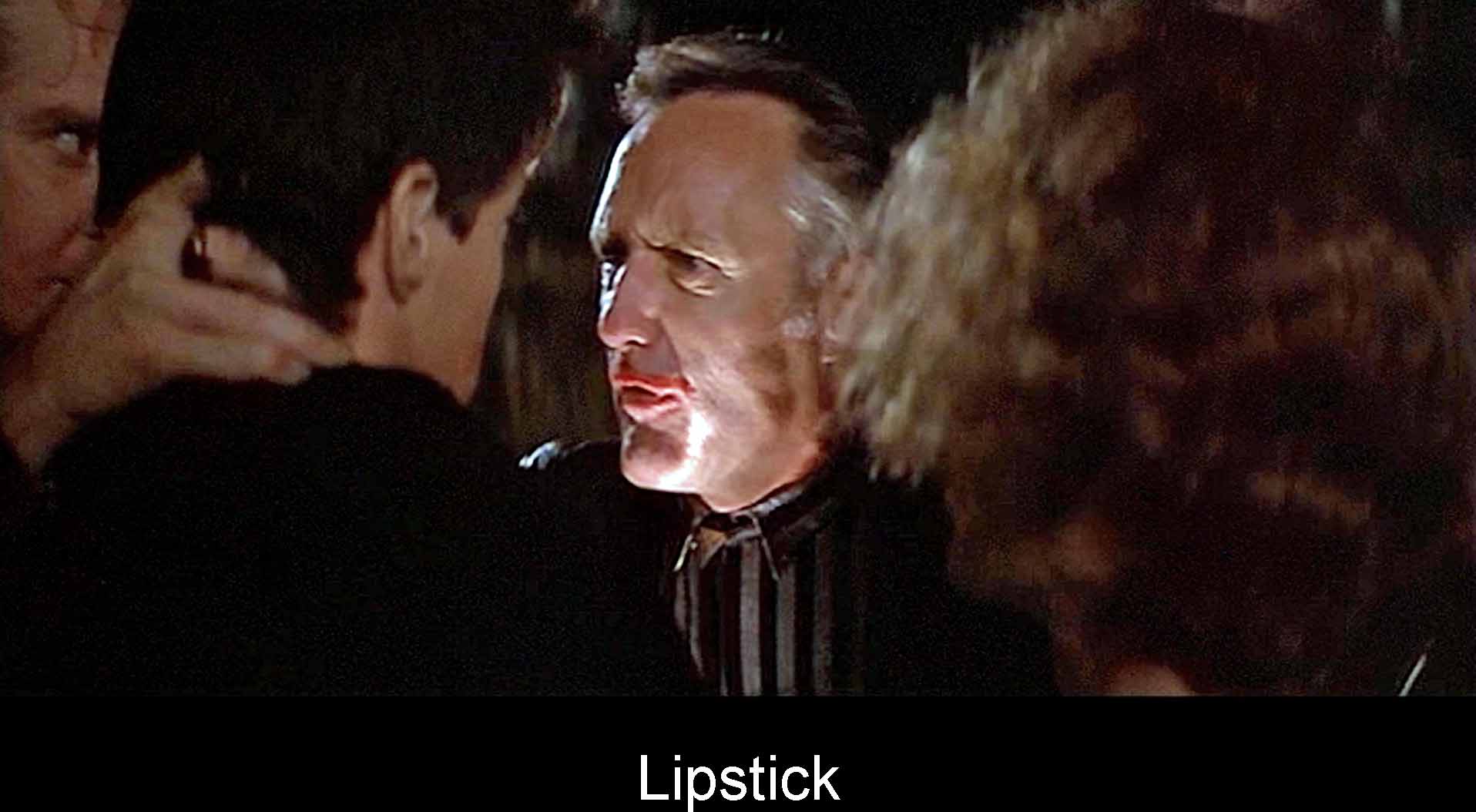

Why the many reds? The roses in the opening shot, the fire truck, police and ambulance lights—they all suggest safety. Red turns sinister with the decor in Dorothy’s apartment, especially the red drapery sinisterly blowing, Dorothy’s extreme lipstick, or the lipstick smearing in the beating of Jeffrey (that echoes the candy-colored clown of Ben’s song). Red’s are part of the double-valuing in the film.

And what about yellow? The yellow jacket of the so-called Yellow Man echoes the brilliant yellow of the tulips in the opening. They are innocent, he not so. More double-valuing (just as he is double: a cop and a crook).

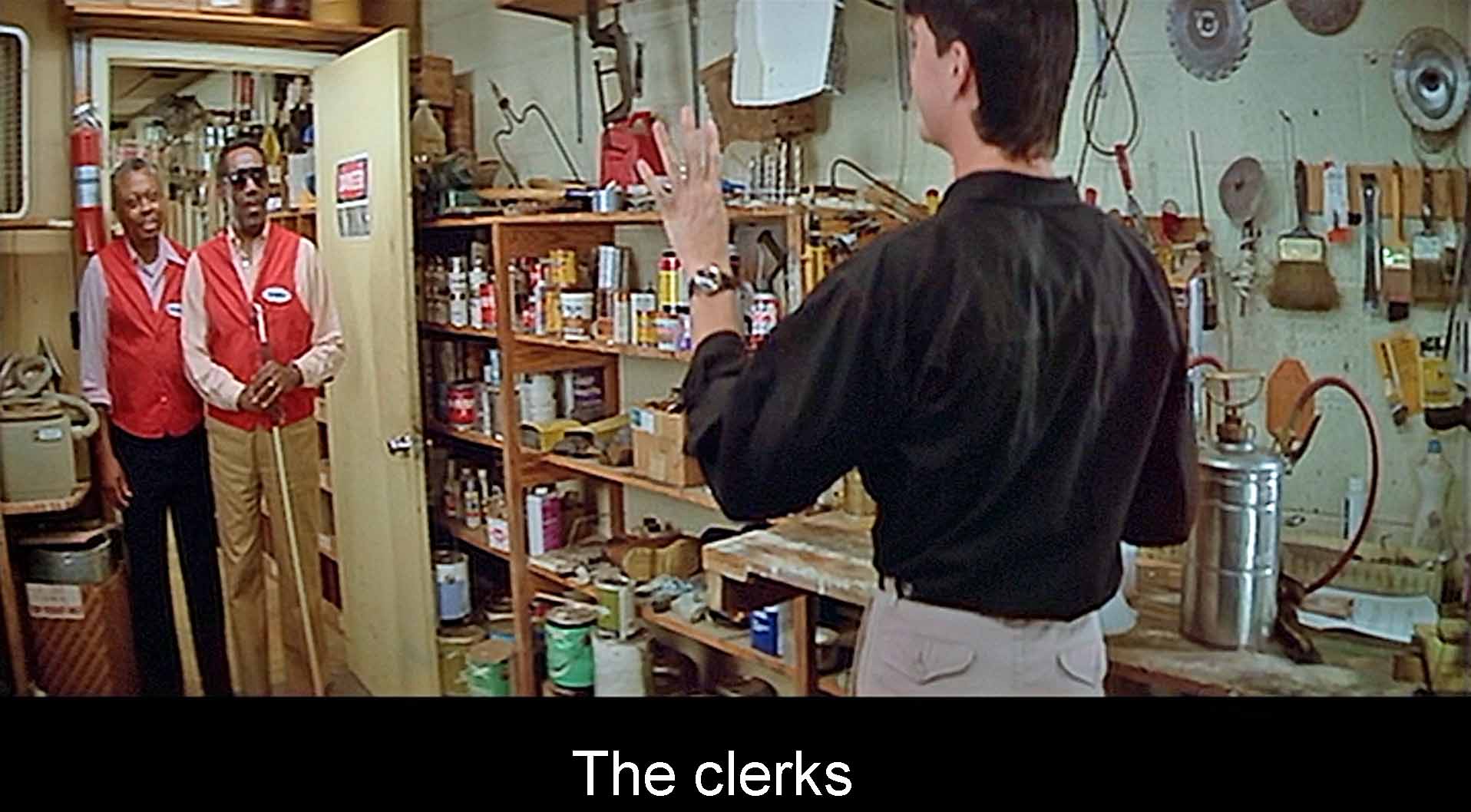

Why the business with the two black clerks in the Beaumonts’ hardware store? Jeffrey describes them as a mystery he can’t solve—like the Dorothy Vallens mystery. Blacks are for show in Lumberton. Touch, the trick by which the sighted clerk helps the blind clerk “see,” corresponds to the way Dorothy’s touch lets Jeffrey see the truth.

Why a shot of the street sign for Lincoln St.? Dorothy has been enslaved, and Jeffrey wants to free her. A less obvious form of slavery is the confining life in idyllic Lumberton.

Why “Deep River” apartments? “Deep River Blues,” a famous blues, continues the blue of Dorothy’s song and housecoat.

Why lumber and lumber trucks? Destructive industry. So too the industrial wastelands we see at Frank’s hideout, and when Jeff wakes up after his beating. Cutting down trees is what keeps dear little Lumberton going. And the timber industry recalls Lynch’s childhood in lumbering country. (Lots of postmodern art asks its viewers to know the artist’s biography.)

Why the flame at the end of “evil” sequences? It’s the opposite of, destruction of, that lumber or wood, the essence of nice “Lumberton.” Contrast the fire truck in the opening, suggesting protection and security.

Why Jeffrey’s “chicken walk”? The youth and naivete of Jeffrey. He is “chicken” compared to Frank.

Why does Jeffrey disguise himself as “the bug man”? He’s the one who could destroy the horrible ants that populate the underside of Lumberton lawns.

What’s Jeffrey’s father’s ailment? It’s described in the screenplay as a stroke, but suggests the danger and hurt lurking within our every day lives. “In the midst of life we are in death.” Or, Sir Thomas Browne’s famous, “This world is not an inn but an hospital.”

Why the wig that Dorothy wears, even when she’s making love? Everything is something else. As Frank turns out to be “the well-dressed man” when he wears a wig.

Why Frank’s obsessively repeating “fuck”? (The only character who does. ) Because much of the “evil” in Blue Velvet has to do with perversions of love and procreation, “fucking.”

Why the “candy-coated clown” in Ben’s song, repeated on the radio when Frank is beating Jeffrey? He smears lipstick on Jeff’s face before beating him up. “You’re like me.” Homosexual and sadistic elements in Frank, more perversion, but a hint that somewhere in Jeffrey, too, can be Evil (as when he hits Dorothy when they’re having sex).

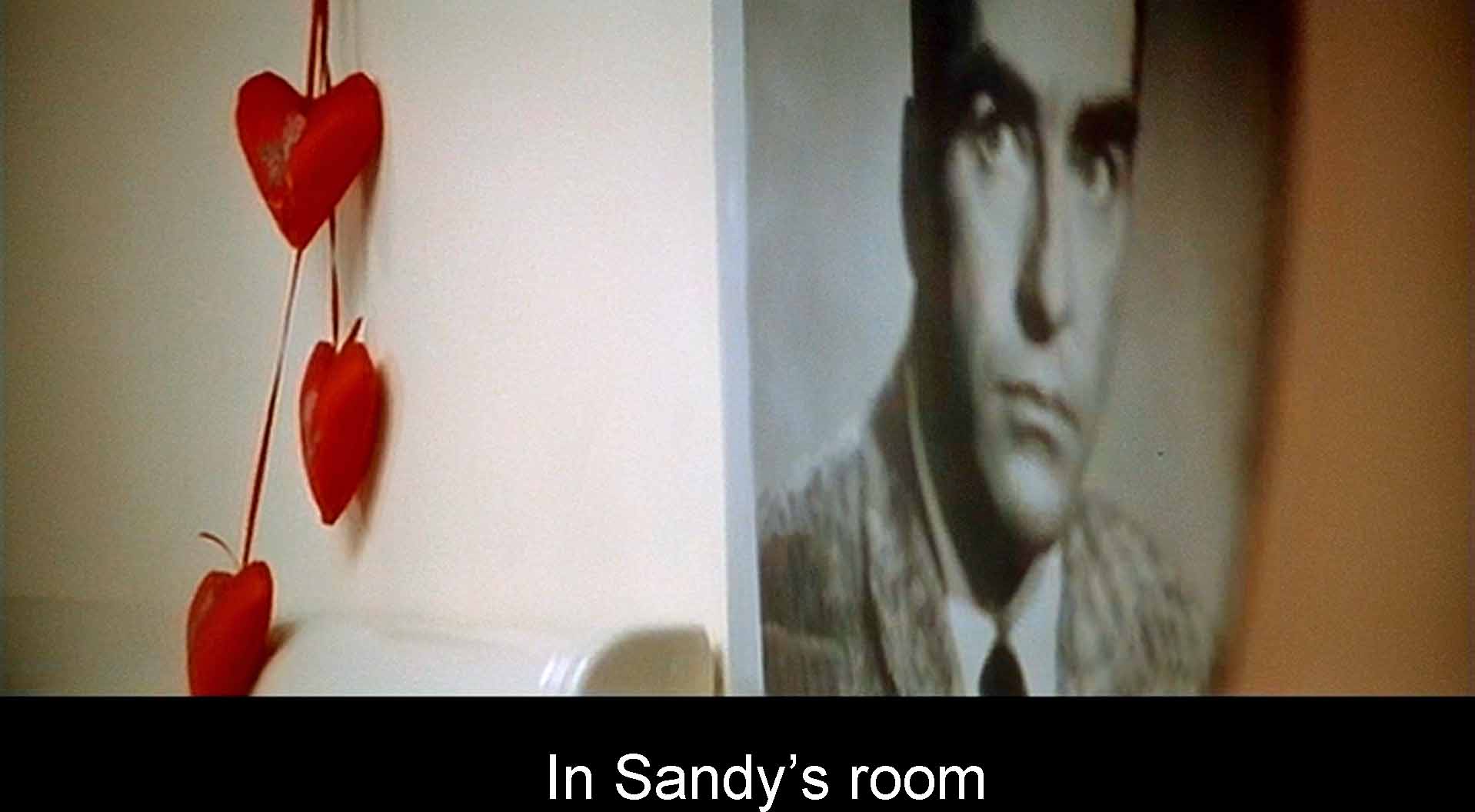

Why a big blow-up of Montgomery Clift in Sandy’s bedroom? I think it’s an echo of Ben (note the jacket). Clift was famous for bisexuality and drugs.