Apur Sansar brings the Apu trilogy to its glowing end. I think it the most human, the most moving, the “best” of the three. I say and everybody who writes about the Apu trilogy says the three films are about progress and motion. When you move forward, you gain something new, but you lose something old. I would say that Satyajit Ray moved forward with this film. He gained great polish in his filmmaking which reaches a peak, I think, in Apur Sansar. But that skill makes his post-Apu films slicker, less deeply moving, at least for me, than this one, which I think is magnificent.

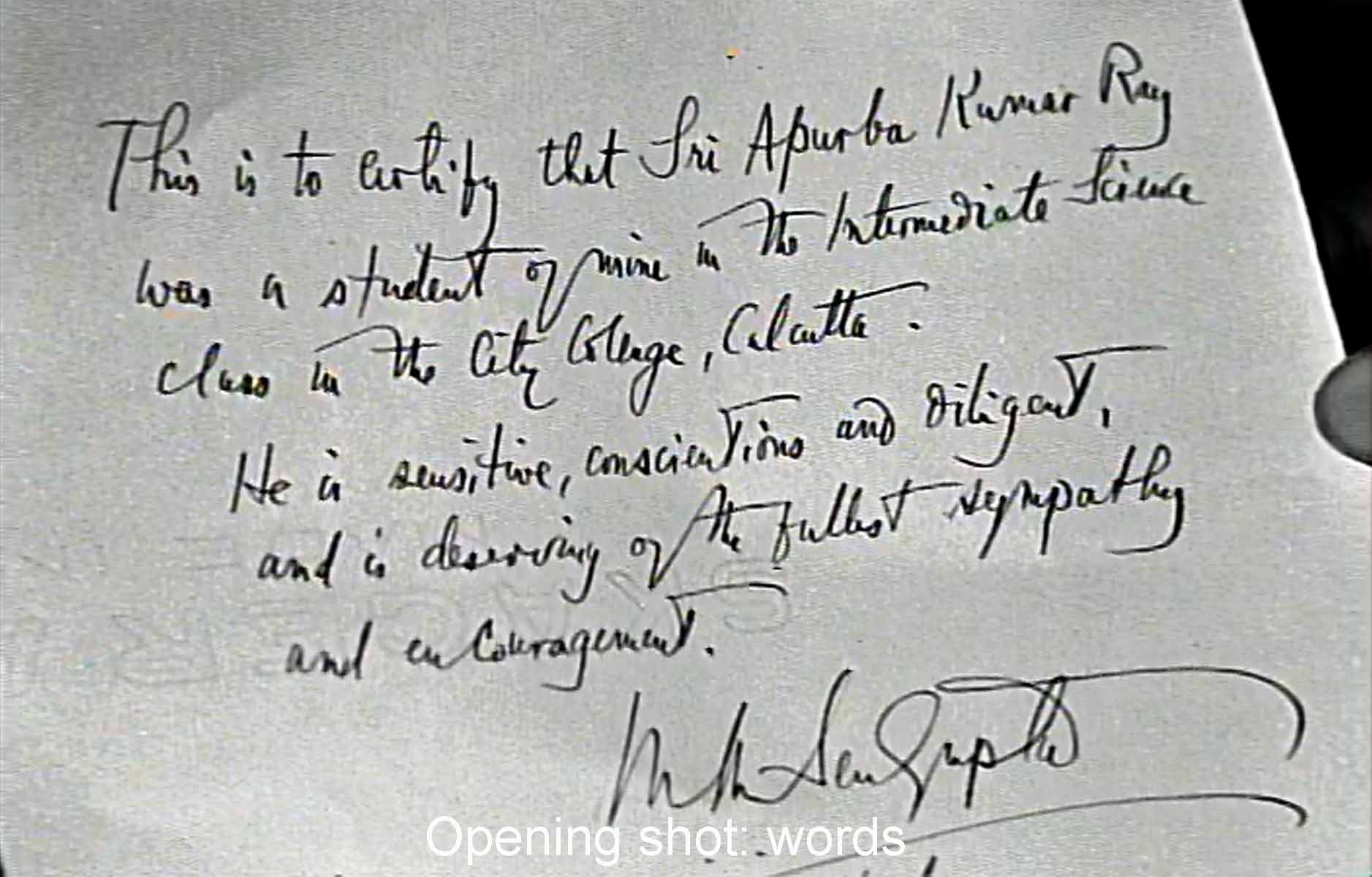

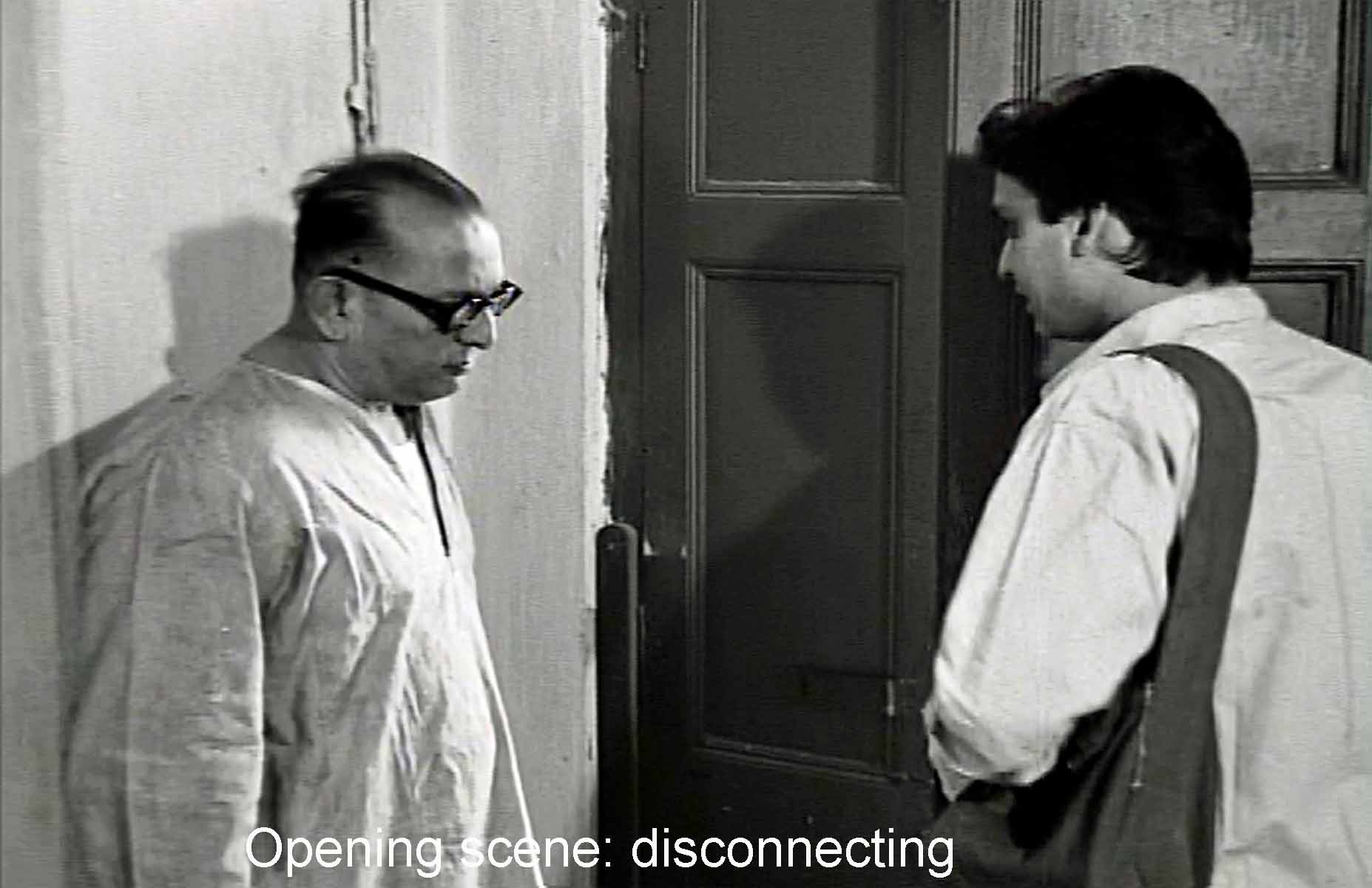

Apur Sansar has five sections. The first occurs even before the credits. The first shot is of words, suggesting the importance of Apu's writing. Then he breaks his connection with the university because he has run out of money. As he lingers in the doorway, we hear a student demonstration outside—a group he is no longer connected to. Words, this short scene, I think, suggests are his substitute for connection.

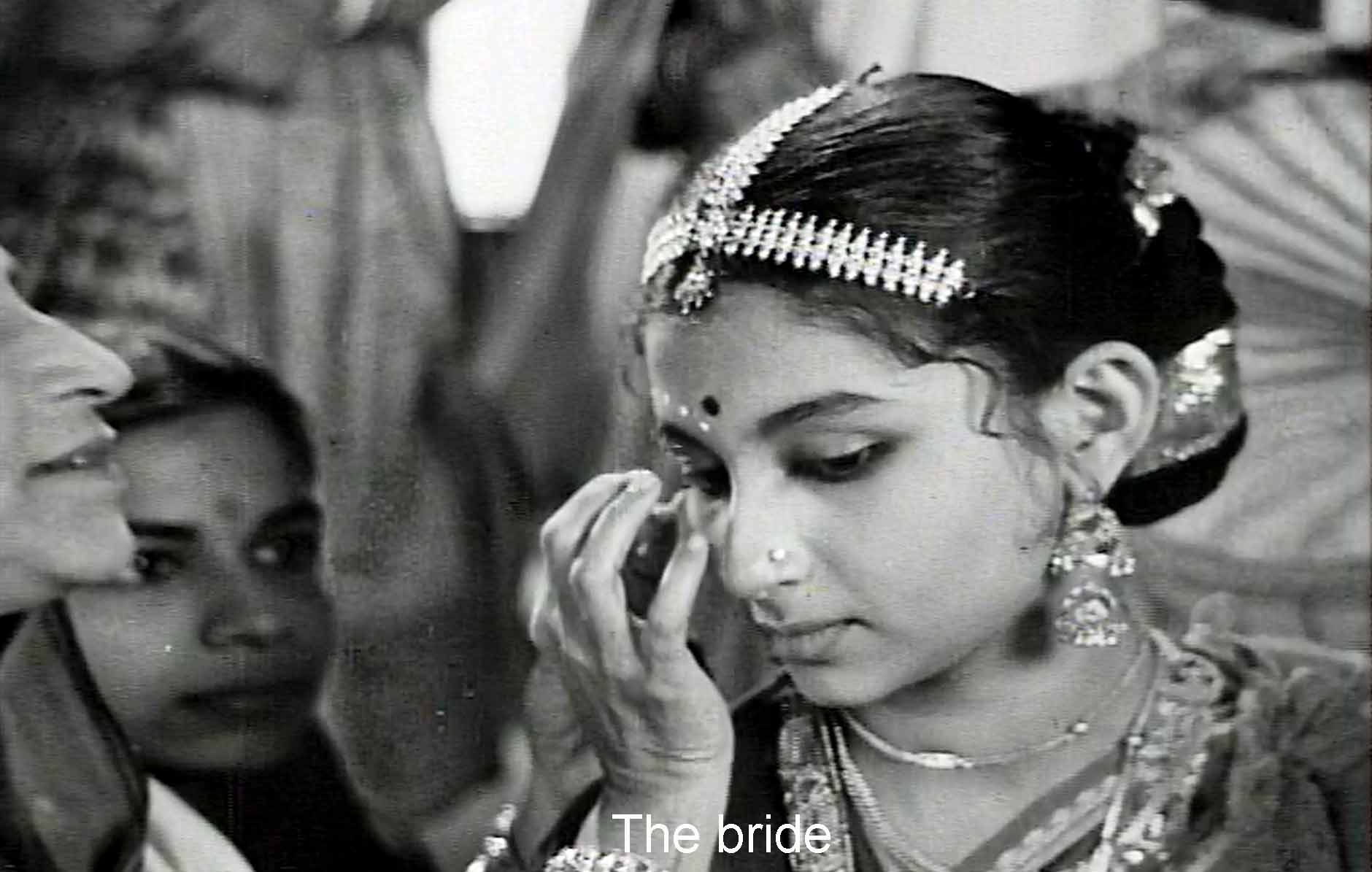

Then come the credits. The actors in this film are special. The subtly expressive Soumitra Chatterjee plays Apu, and he went on to make fourteen more films with Ray. Pulu is Swapan Mukherjee, a capable actor who radiates solidity and reassurance in this film. But the star for me is Sharmila Tagore (of that extraordinary family). She was a schoolgirl, only thirteen!, when Ray cast her as the bride Aparna in this film. She made just one more film with Ray, Devi (1960). (My essay is at: http://www.asharperfocus.com/Devi1.html.) It shows a young bride destroyed because the superstitious people around her think she is a goddess. Sharmila Tagore went on to a long and distinguished career in Indian cinema.

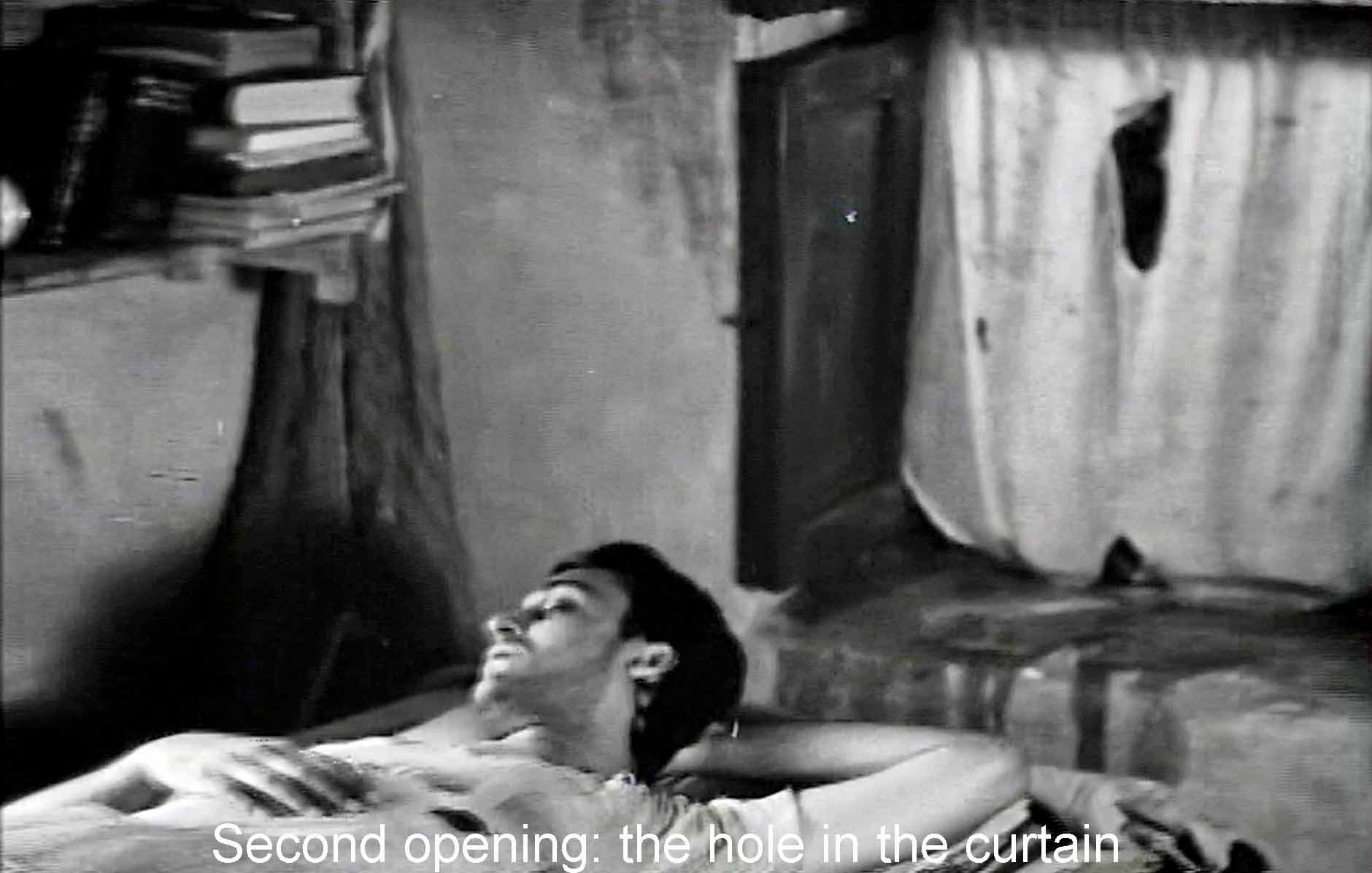

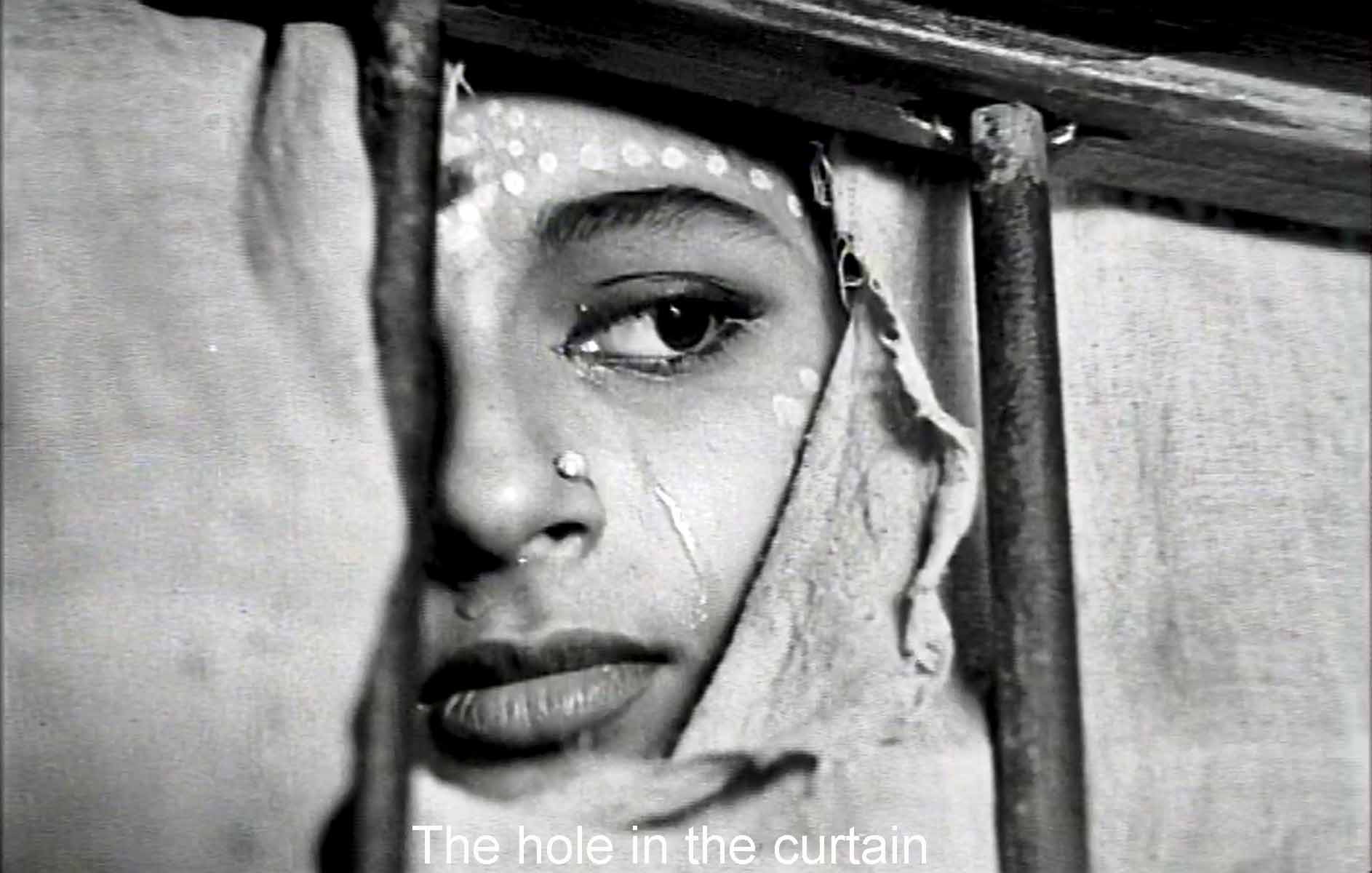

The second section begins: We see Apu asleep in his wretched room at the top of a building next to the railroad. A hole in a curtain suggests his limited connection with the world outside. A train whistle wakes him up. At this time, he is writing his novel, spilling ink on his bed (as he did in Aparajito), playing his flute, and hiding from a possibly attractive woman next door. The landlord demands his rent, good-naturedly, as befits dealing with an educated man. Apu goes out to pawn some of his books and try for various jobs. (He is over-qualified, but perhaps that is fortunate given the jobs.) Poverty and the need to have a job form major motivators in all three Apu films.

The third section begins when his friend Pulu, an engineering student, turns up, feeds him a decent meal, encourages his writing, and invites him to attend his rich cousin’s wedding in the country. This is a traditional Indian wedding, an arranged marriage. The bride and groom have never met. In this third section a very strange outer force takes over. The groom arrives in a palanquin accompanied by a band playing “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” (Remember Apu watching the band in the first film? This time he sleeps.). The groom, far from being a jolly good fellow, is insane.

What to do? As in Aparajito, traditional ways conflict with modernity and common sense. Astrology dictates the time of the wedding. If the bride does not marry by the astrologically auspicious hour, she can never ever marry. A tragedy! A tough old grandfather wants the wedding to take place anyway, but Pulu begs his friend Apu to take the groom’s place. Apu, ever compassionate, does.

Now begins the truly idyllic fourth section with some of the most subtle and charming images of love beginning and ripening between Apu and Aparna that have ever graced a film. But, of course, in a film about progress and loss and connection-disconnection, this lyrical love has to come to an end. I do not believe in spoilers. Even if you know what’s coming next, for a knowing viewer the beauty of the film remains. But most people do believe in spoilers so I won’t, for the time being, tell you how or why this section ends, but it does.

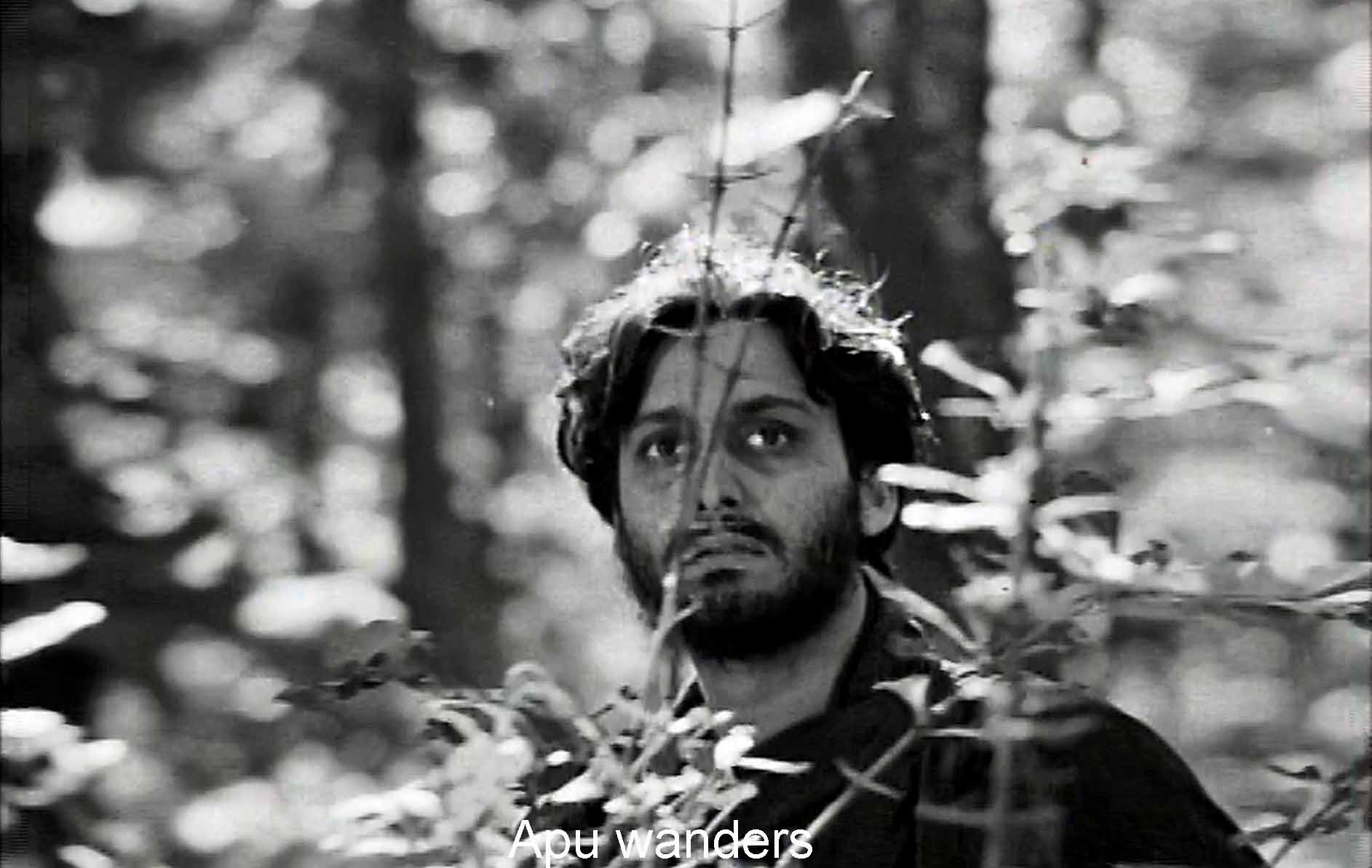

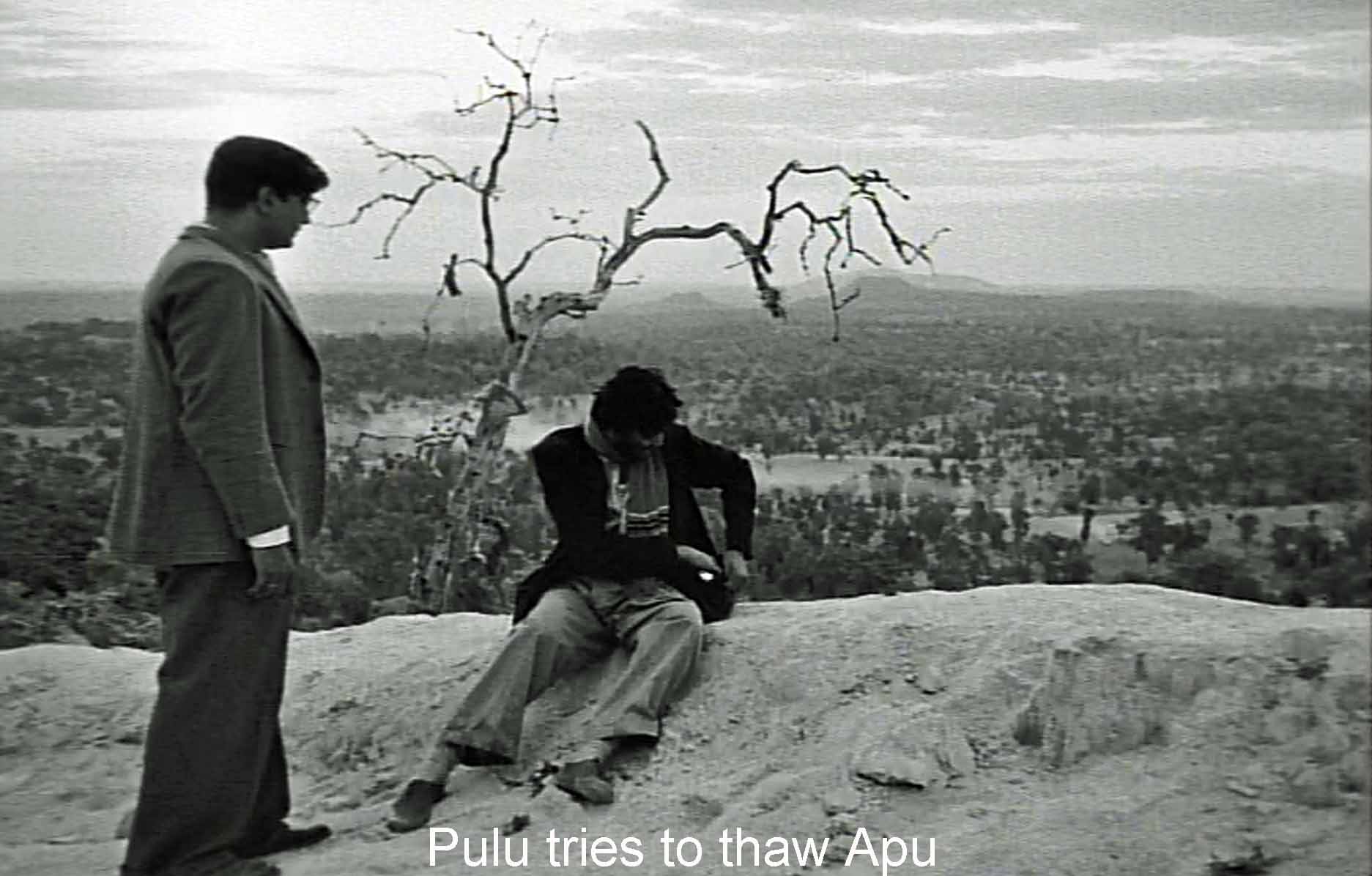

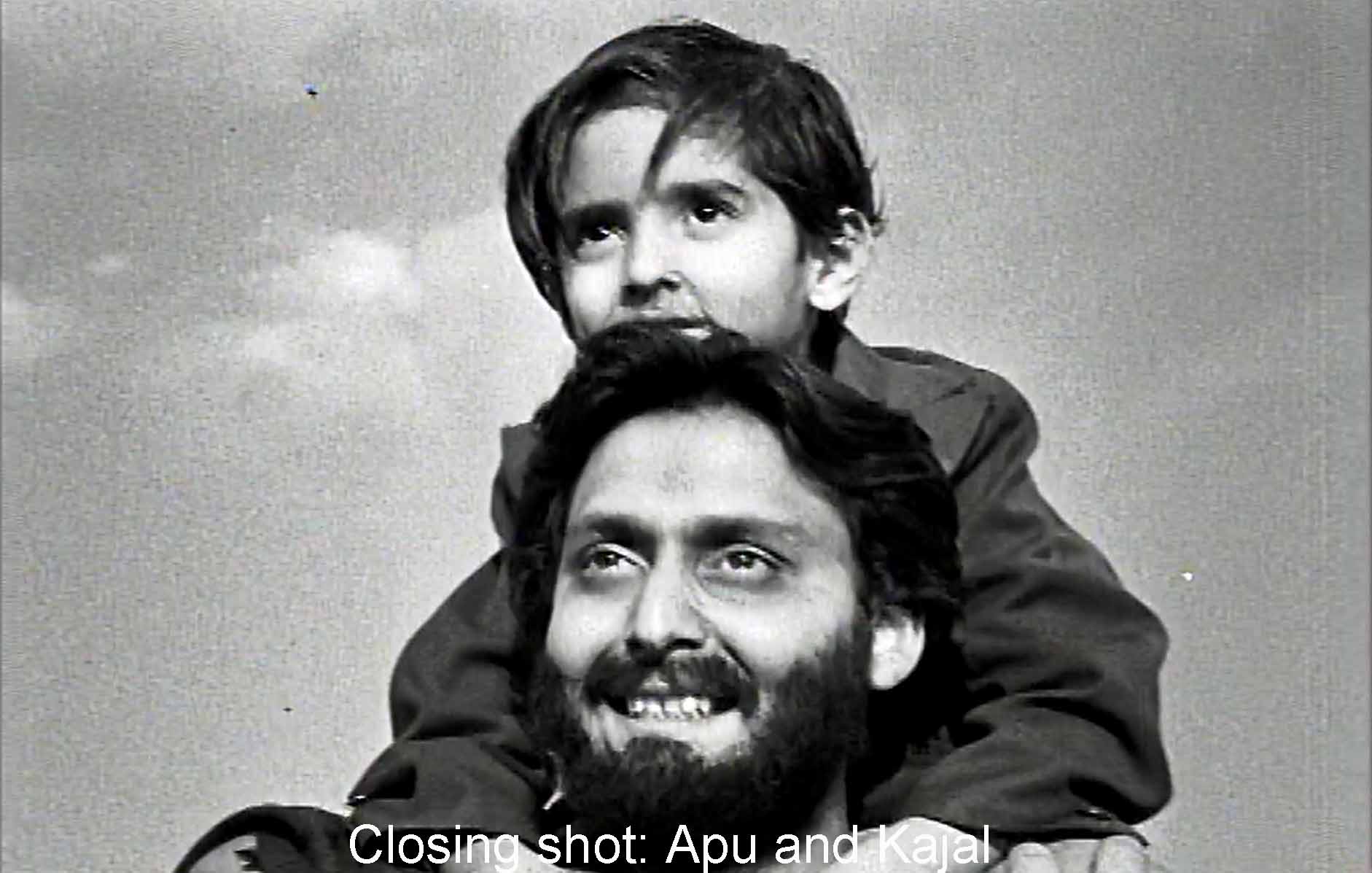

The fifth section: Apu now has an infant son, Kajal, but for five years he wanders all over India through a variety of landscapes: ocean, forest, mountains, ignoring and avoiding that son. Finally he ends up working at a coal mine (the depths?) where Pulu catches up with him. With difficulty Pulu persuades Apu to go and see his son Kajal (compassion again). The boy (Alok Chakravarti) seems about the same age as Apu when we first met him in Pather Panchali. He has been growing up wild, disobedient, destructive, cruel, violent, but the boy’s first appearance in a fierce mask suggests that this is not his true nature. At first he rejects his father, but compassionate Apu saves him from a nasty beating at the hands of his grandfather (tradition again). The boy then finally accepts Apu as a “friend.”

The ending rounds out the trilogy. I found it interesting that in one moment of the final section Apu proposed putting the boy back in his own original village. That would make the trilogy go nowhere. Instead, Apu has progressed from a child this boy’s age to an adolescent student, then a man, husband, and father. Contrast the boy Apu aimlessly running around a forest in Pather Panchali with this boy smilingly looking into a future.

I think Apur Sansar is about progress, yes, but even more, connectedness (and indeed you could read the first two films that way). In this film Apu is a man who does not like to be connected. He prefers imagination: writing his novel; reciting poetry; playing his flute; imagining love—things that go from inside him outward. If you are connected to someone, that movement is reversed. Outside forces control you: economic need, astrology, tradition, religion, family, love. Here, Apu gets connected with a woman in the most intimate way possible. That connection ends, and he is disconnected again. Finally he connects with his abandoned son, who reminds me very much of Apu when we first met him in Pather Panchali.

I’m disappointed when critics settle for telling me about Ray’s humanity, his humility, his vision, his imagination, or how his films are like a great river. He deserves better. In Apur Sansar he returns fully and triumphantly to the unique style of Pather Panchali. He picks up details here and there, everyday details that are part of ordinary life or that grow naturally out of the plot. But a strong critical reading sees them commenting on and enlarging the action. I feel them taking me deeper into the film.

Some of these details come from the novel: Pulu is an engineer, and he engineers various changes in Apu’s life. The characters travel by train, because that’s how you traveled in India in the 1910s and ’20s. Trains are one motif in the trilogy; poverty is another. Throughout, poverty rules the character’s lives, and the need to find work governs their moves. This is simply the original novel’s portrayal of life in India in the 1910s and ’20s, but Ray uses it to image forces acting on the characters from outside in. But other meaningful details come from Ray’s mise en scène, what he puts on the screen before us.

Water: When we see Apu waking up in this film, it is raining, and he goes out into the rain and delights in it as Durga had delighted in the monsoon in the first film. Throughout, water becomes a sign of change, flow, if you will, as in the wedding that takes place beside water. Conversely waters are frozen when Pulu tries at first unsuccessfully to persuade his friend to accept his son. And finally there is water alongside father’s and son’s act of mutual acceptance.

A minor detail: The curtain covering the window in Apu’s wretched room has a hole in it. When he brings his bride there we see her single eye peering through the hole as we saw the boy Apu’s eye when we first met him in Pather Panchali. Like him, she is a perceiver of the details of Apu’s situation. This is one of many details in the last film of the trilogy that hark back to details in the earlier films. Watching the first two films after seeing the third made me appreciate them all the more.

That curtain (which she quickly replaces) represents one more in the many doorways and gateways and windows that occur all through the three films, associated with moments of change. Significantly, Apu closes the shutters on the window that might expose him to the woman next door. Pulu shows up, at first invisible, in Apu’s doorway. Doorways mark the stages in the marriage. But Apu’s final growth comes in the open. He leaves doorways behind.

Another minor detail: There is a film-within-the-film in Apur Sansar, a thoroughly unreal mythological Krishna story. (Krishna plays the flute as Apu does.) After Apu and Aparna see the film Ray cuts to a moment of very human intimacy between them. Apu asks Aparna what she has on her eyes. “Kohl,” she replies in the subtitles, but the Bengali word (Andrew Robinson explains) is “Kajal”—the name of their son-to-be. Detail after detail like this winds through the three films.

The trilogy is about progress and, I think, connection. The train and the train’s motion stand for both, and trains play more and more of a role as we advance through the three films. In Pather Panchali, the train stands for progress, far off and out of reach of these poor villagers. In Aparajito, it takes the family from their wretched life in the village to a somewhat better life in Benares, but then it enables Apu’s move to Calcutta and his college education. The train takes him forward, but it also separates him from his dying mother. Finally, in Apur Sansar, a disconnected Apu finds connection again. He progresses from a stunted bachelor existence to being a husband and a father, but with a terrible loss along the way marked by a train. You gain some, but you lose some.

Inevitably, it is a train that brings Apu’s bride Aparna to his apartment and the noise and mess of the nearby trains. It is a train that takes her back to her family—that’s how you travel. But also, trains both separate as well as unite people. As Mamoun Hassan says (in his fine commentary on the Criterion DVD), the trains we see are big and black and ominous. They presage each of the deaths that occur in each of the three films: Durga and Auntie in the first, the father and mother in the second. Trains signify progress, yes, but also loss.

I like to end these essays with a laudatory sign-off. With the magnificent Apu trilogy, there is no need. Apur Sansar says it all.

I’ve drawn on: Andrew Robinson. Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye. 2d ed. London: I. B. Tauris, 2004.