To me, Devi is a puzzling and (in a technical sense) mysterious film. I find at its core a paradox that flips back and forth like an optical illusion, an ambiguity like what Freud called “the navel of the dream,” a strangeness like the religiosity that bedevils India. Perhaps the best way to begin to unfold that ambiguity is to recall the film simply at its story level.

In Bengal of 1860, a husband, Uma (played by Soumitra Chatterjee), leaves his girl-wife Doya (the legendary Sharmila Tagore) and his rich, high-caste Brahmin home to study English at the university in Calcutta. He speaks in favor of the Brahmo Samaj, a movement founded by Romo Han Roy in 1828. It held that one should learn the English language and ways, give up Indian cult religions for Christianity, replace traditional medicine with modern medicine, and support the younger generation against the total power traditionally accorded the Hindu father.

While Uma is gone, life goes on in the village in its sleepy way. Doya plays with her little nephew, Khoka (son of Uma’s elder brother). She strokes the family parrot. She provides food and water offerings for the shrine of Kali, whom Uma’s father, Kalinkar (Chhabi Biswas) obsessively worships.

Kali, often represented as the consort of Shiva, is a darker side of Devi. Devi, which means goddess, is a female aspect of the over-arching agent of creation and change, Shakti. Kali is a mother-goddess, addressed as “Ma,” but she, like Persephone, represents the cycle of seasons, hence time, hence change, and thus, ultimately, death, but she is both creator and destroyer. When she is the destroyer, she is associated with death, disease, and drought, her image is black, she wears a necklace of skulls and snakes, and she tramples on the head of her husband Siva. Thus she shows her power, that she is as strong as Siva, but she does not crush his head, proving that she is not stronger than he. When she is the dispeller of disease, her image is white and she wears garlands of flowers.

Durga is another mother goddess, but a more benevolent aspect of Shakti than Kali. She is particularly popular in Ray’s Bengal. As the film opens, Uma, Doya and Khoka watch the villagers celebrating the Durga Puja, a ceremony in which life-sized images of Durga are put in the local river. This exuberant worship of benevolent Durga contrasts with what is to follow, involving the more deadly Kali-aspect of the female. But apparently Kali is included in the festival, for the villagers chant, "Durga Kali, Durga Kali."

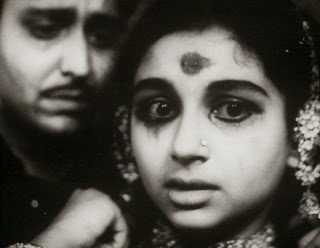

Uma’s father Kalinkar adores Doya but worships Kali. The old man has a dream in which he identifies the bindi of Kali with Doya’s bindi. On waking, he bows down before her as the incarnate goddess, and the elder brother and the holy men of the village follow suit. A beggar brings his dying child to her, and the child recovers. This “miracle” convinces the rest of the community and, when her distressed husband returns and tries to get her to run away with him, she demurs, wondering if she really is the goddess. Long lines of worshippers now seek the favors of the “living goddess.” When her nephew Khoka falls ill, however, and the family put aside medical care for “the power of the goddess,” she fails to cure him. He dies, and when Uma returns he finds father, elder brother, and sister-in-law all grief-stricken and resentful. His wife has gone mad. She runs out into the radiant fields, and her image dissolves into the smiling stone face of an ancient goddess.

The film begins, however, decisively enough with an almost trite contrast between traditional Indian and modern English ways. The opening shot cuts dramatically from the animal sacrifice (of a castrated goat) at a festival for Durga-Kali to fireworks with a brass band playing “Col. Bogey’s March” in the background. The “older generation” (father, elder brother) worship Kali. The “younger generation,” Doya, Uma, and Khoka, enjoy the fireworks.

We see more of this contrast later, in Calcutta. There the young men who follow Roy’s example wear socks and garters and English shoes. They ride carriages and smoke cigarettes (instead of hookahs). They lapse occasionally into English. They watch a play about laughing at your ancestors (it could even be a Bengali version of Aristophanes’ The Clouds—after all, the issue is the same). One young man talks about marrying a widow against custom and his father’s wishes. Uma asks advice, not of a holy man, but a professor (who has a picture of Shakespeare on the wall, instead of some guru—or is Shakespeare a guru?).

The cultural contrast, however, reflects others, between the generations and the sexes. All the men in the film are trying to possess a mother-figure. Khoka wants Doya as a mother (and links her to a story about a witch who eats the bones of little children). His grandfather uses Doya as a “little mother.” Uma’s elder brother comes to worship her as a goddess. Her husband, of course, wants her as a wife, the submissive, child-like traditional Indian bride. Uma’s friend wants to marry a widow. The beggar loses the goddess, then gets her. The old holy men worship her.

But Doya-Kali is a triple goddess. She has three relations to the male. She plays with the child Khoka, she lies with her husband, and she tends her husband’s old father, sensuously washing his feet. He treats her as a mother much as Khoka does. Conversely, the males show the three essential roles of man to woman (as spelled out in Freud’s “Theme of the Three Caskets” or many writings of Robert Graves). To woman, man can be child, lover, or dotard (about to be scooped up by the earth—or death-goddess). Indeed, the father, when he talks about walking with a cane, could be making an explicit reference to Oedipus’ riddle. Anyway, we do see the three ages of man as in the riddle of the sphinx: Khoka, just past the four-legged stage; Uma, two-legged; and the father, the three-legged old man with a stick.

The men are rivals for Doya, as wife, mother or goddess. Moreover, the struggle takes place across generational lines in the classical manner of the Oedipus complex. Uma is the husband in the middle. His father orders her about as his body servant. The child Khoka charms the wife away as a child captures a mother. Uma loses all around.

Further, the cultural struggle mirrors the generations. The father and older brother (who also carries a cane and who does whatever his father tells him) represent the old culture. Uma, his friend, his professor, and the Calcutta scene represent the new generation. The relation between man and woman gets caught up in the generational conflict, as Doya mothers both the little boy and the old man—and stops being a wife to her age-mate.

There is a specifically Indian theme about the sexes here, too: Shiva and Shakti. Divine mates, they are respectively the male and female gods of creation and destruction. The worship of Shiva addresses what the father in this film recites from the sacred texts: “the male spirit, vast, all-powerful, unchanging.” In worshipping Shakti, the female principle, however, the worshipper is to become like a child, abject, helpless, dependent, and that is what those who worship Kali become in this film: the beggar, the father, the brother (drunk on holy wine). The beggar’s two songs to the goddess, the first petulant, the second adoring, are like a child’s moods with its mother.

Doya, the goddess, “devi,” is both the astonishing image that opens the film, the appalling religious power, and the familiar, everyday nurturing Indian mother, the “Ma” repeated throughout the film. Thus, the relation between the sexes—is Doya Uma’s wife or a living goddess?—becomes tangled up in the relation between the divine and the mundane. Ray develops this double level of the film through a variety of incidental images.

Repeatedly, birds fly in and out of the shrine, between heaven and earth. They are sacred to Kali (as to Persephone), because they fly between heaven and earth. In the house, however, there is a pet parrot, always speaking to humans—and adored by Doya in her secular aspect. This bird is earthbound, limited to a human, not a heavenly dimension.

Developing the same theme, Ray repeatedly shows us feet. Doya washes her father-in-law’s feet. When he decides she is divine, he bows down to her feet. She, however, curls them back, embarrassedly resisting the role he is forcing on her. When Uma returns and stares at his wife being worshipped, feet appear in the upper right of the frame. Perhaps Ray wanted to show feet because Kali steps on the heads of her foes and her husband, perhaps as another reference to the Oedipus riddle. Perhaps he referred to feet simply because feet are the way we rest on the firm ground of earthly reality.

I see as related Ray’s many shots of people walking along the road home or in the house toward the mother-Doya. The film seems to me to ask: Who can walk how? With a cane? Down the hall to the goddess? Down the hall to the father? Along the dusty road? All ways of reaching out toward—something.

Water. Kali protects against drought—that is why images of her Durga-aspect were thrown in the water after the opening shots of the festival. Doya gives water and candy to Khoka, places fruit and water in the household shrine, administers medicine and water to the father. The beggar’s sick child has not swallowed water in eight days. He is cured by having the milk (of Kali) poured between his lips. The husband wants to escape over the water, but Doya pulls back at the water’s edge: she has seen the fragments of an image of Durga or Kali. It is at this point that she asks, “What if I am the goddess?”

In the end, of course, she is. She is both the dispeller of disease and the destroyer who has caused the death of her beloved Khoka. Sanskrit devi means divine (cp. Lat. deus, Gr. Zeus, etc.) It also means “to shine,” and Doya dissolves into the light at the end. They are all gone into the fields of light.

Ray cuts from her disappearance to a stone image at the end that could be archaic Greek, southeast Asian, even Central American: the mother goddess is universal, and Doya in her madness has disappeared into that plane. Earlier, the grateful beggar had said, “Your face is not stone.” Now her face is stone. On the wedding night, her husband said, “You are a china doll. You have the face of a goddess.” Now she is and does in a different dimension.

The old man who believed her into being a goddess now asks, “How have I sinned?” A recurring question by all believers who don’t get what they pray for—or do. Rather than believe she isn’t a goddess, the man of faith would rather say he himself sinned. His sin justifies the goddess’ failure. And he did sin. He did not go on the begging pilgrimage ordained for all pious Brahmins (as, for example, the beggar does). “I couldn’t walk without a stick.” Having failed his obligations, having chosen instead to live in great comfort (Ray details the luxury of his life in the first third of the film), he is now terribly punished. The old man’s delusion that Doya is Kali comes from his failure to observe the right pieties and leads to the crazy belief in Doya-Kali that destroys his beloved grandchild. That would be a religious reading. Whom the gods would destroy, they first make mad.

Ray cuts dramatically across the conflicts he has set up: from one sex to the other, one generation to another, one culture to another. But then he lingers in long close-ups on the individual face. I feel I am watching the character’s mental processes, the little boy savoring his candy, for example. But, of course, the camera can only photograph surfaces. It can never really show me a mental process. Thus, Ray’s camera work builds on what seems to me the central ambiguity of the film.

The film exquisitely entwines the psychological with the supernatural. It leaves me no way to split off some religious being-beyond from our everyday being-in-the-world. The boy asks Doya for a story about a witch—prosaic enough, as a story—but then Doya becomes that witch.

The film gives a perfectly rational, natural psychological explanation for a half-supernatural punishment. Ray’s and cinematographer Subrata Mitra’s camera work intensify the psychological with sounds of the household and small camera movements and shots of the household surroundings. The folkish music, a sarod played by Ali Akbar Khan, adds to the earthy realism. The old man believes too much that Doya is Kali—perhaps because he is a little in lust with his charming daughter-in-law. He disguises his sinful feelings for her by believing she is the goddess. The beggar’s child gets well. Then others believe Doya is the goddess. Instead of getting science-based medicine for Khoka, the old man and the brother insist on relying on a faith cure from Kali. And they lose the child. Yet at the end she has become the goddess. She is the creator and destroyer. Faith creates the object that creates faith (as in Shaw’s definition of a miracle: “an event which creates faith.”)

This is for me a film about faith and the way faith itself is a creator and destroyer like Kali, because faith creates one reality and destroys another. We can no more live without faiths than we could survive without a mother—even if she be destroyer as well as creator. Our every act, our every perception, builds on hypotheses about the world, a basic trust in its constancy, in its materiality, in our ability to know it, in short, faiths. We could not see this film or any other without some such system of faiths about the world, although our belief in even so fine a film as this one is a belief in an illusion. Only by believing, though, can we find the truth—which turns out to rest once more on belief. This is, then, a film about faith, the terrifying duality of faith. No wonder she goes mad at the end. No wonder India or the U.S.—both lands dense with religion—lurch between a pious search for peace and maddened genocide. Satyajit Ray dramatizes in Devi a psychological truth we all must suffer.