In 1960, Orson Welles had high praise for Shoeshine. Usually, critics quote it this way: “The camera disappeared, the screen disappeared, it was just life.” That hardly says much for De Sica's artistry, does it? Quoted fully, what Welles said was, “In handling a camera I feel that I have no peer. But what De Sica can do, I can't do. I ran his Shoeshine recently and the camera disappeared, the screen disappeared; it was just life . . .” For all the talk about the film's realism, justifiable talk surely, Shoeshine is still a deliberately shaped work of art, in which De Sica does thoughtful things with his camera, building on the scriptwriting of the immensely talented Cesare Zavattini.

In focusing on “just life,” the critics are stressing Shoeshine's place in film history as one of the cornerstones of Italian neo-realismo. The neo-realist movement stressed filming on location, the use of non-professional actors, and a focus on the miseries of the poorest citizens of Italy during the U.S. occupation. The Italian title Sciuscià is what the boys would call out to the G.I.s: Sciuscià, Gio?, Shoeshine, Joe?

It is sometimes said that Italian directors had to turn to neo-realism because they had no money, but that is not true. Other Italian directors, besides the neo-realismo directors like De Sica, were making expensive-looking films during this period. Neo-realism was an artistic choice, influenced by American film noir and by the “poetic realism” of French directors like Jean Renoir. It represented a decisive turning away from the luxurious “white telephone” style favored by Mussolini toward Marxist themes and an emphasis on the poverty and desperation the lower classes were experiencing under American occupation.

The film focuses on two boys to represent those suffering classes, Pasquale Maggi (Franco Interlenghi) and Giuseppe Filippilucci (Rinaldo Smordoni). Both were non-professional actors, recruited to enact the true story of two other, less attractive shoeshine boys.. So far from this film's being simply a portrait of life, though, De Sica would go through as many as thirty-nine takes before getting what he wanted from his non-professionals.

This movie goes from friendship to murder. It begins with the bright, joyous sequence of the opening horse race to the darkly poetic, and operatically tragic, final scene when one friend is guilty of the murder of the other. In between, they are pulled further and further apart by their separation in prison, by the guards, by Giuseppe's family pitting them one against the other, by the deceptions of the police and the jailers, by their fellow-prisoners, and by Giuseppe's lawyer's trying to make Pasquale guilty to set his client free.

Men. How intensely male the dominant forces in the movie are: the G.I.s, the criminals, the cops, the jailers, the judges. And the subjugated are male as well: the boys earning money by shining the shoes of the G.I.s, one response to an invading army of men.

By contrast, the few women in the film are victims of this brutal, deceptive male regime. They are few in this all-male atmosphere: the fortune-teller who is robbed; the go-between who helps inform Giuseppe's family of his arrest; the prostitutes at Panza's table whom he orders around; loving, compassionate little Nannarella, Giuseppe's friend; even the deceptive statue of Justice at the courthouse (which may be the Queen). But above all, the very emblem of woman is Giuseppe's mother grieving as both her sons are arrested and sent to prison. All the women are victims in this dog-eat-dog environment.

One woman, the fortune-teller, apparently tries to unify. (The commissioner and his wife, perhaps, and she tells the boys' fortunes together.) But she also relies on the scheming deceptions needed to manipulate others in this impoverished society.

The men constantly use deception to control the boys and to survive. The criminals' robbery depends on pretense. The guards get the truth out of Pasquale by pretending that they are beating his friend. The lawyer fakes Giuseppe's defense. The guards at the prison lie and steal. All these pretenses and deceptions form an ironic contrast to the total realism of the film's style. It is honest in its picture of dishonesty.

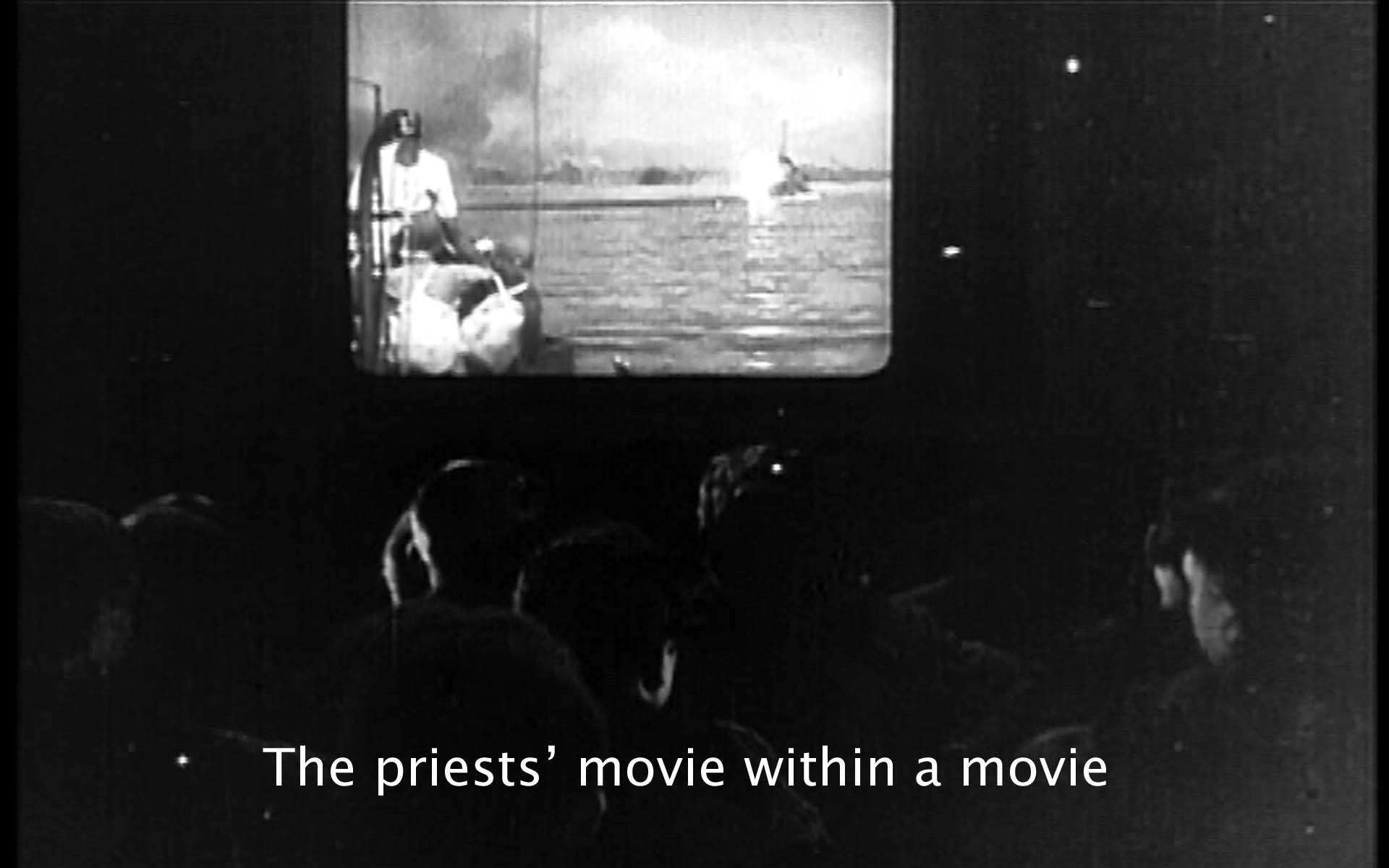

This film has a film-within-the-film, the newsreel of the War in the Pacific. The surrounding story is fictional, but this is real. Although sponsored by priests (male, of course) it represents the very opposite of the bonding that is, in this film, virtue. The newsreel shows battles, invasions, explosions, killing, battles, the extreme but totally real form of this male world. One shot of the sea punctuates the explosions, the one thing in all this enmity admired by the dying boy Raffaele (Annielo Mele) who came from a family of fishermen. But then the film itself goes up in flames, and the boys trample Raffaele to death.

During the commotion we get another alternative to bonding, the escape organized by the bully Arcangeli (Bruno Ortenzi). The escape splits the cohesive group in the prison. It leads Pasquale to betray his friend's plan for flight, namely, the horse that plays so prominent a role in this movie.

Why a horse? It is featured in both the opening and closing sequences. Its name is Bersagliere, a soldier in an elite Italian regiment, something these Italian boys can be proud of. At one point, Pasquale and Giuseppe ride their horse proudly through the streets of Rome, looking down at the admiring shoeshine boys.

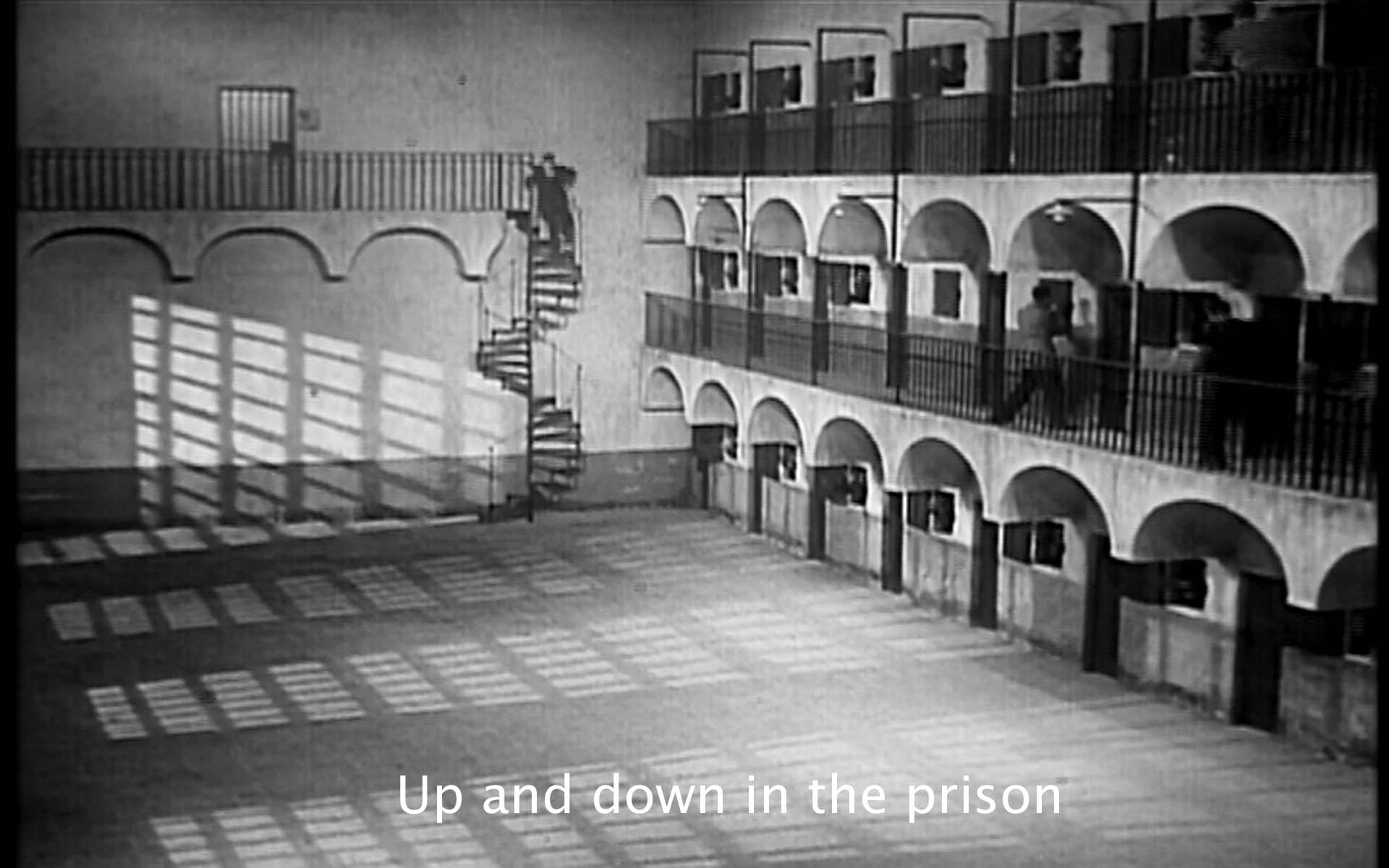

The dominant image in this movie is also the easiest to miss, up and down. The shoeshine boys kneel at the feet of the occupying soldiers, emblem of the national defeat and shame. By contrast, Pasquale and Giuseppe are up, in every sense of the word, in the opening horse race and when they ride their horse past the other shoeshine boys looking up at them. In the final, mystical death scene, Giuseppe is tragically down at the water's edge. Earlier, the low land at the river shore had been the scene of the fence Panza's crooked operations, the beginning of the boys' separation and defeat. The boys climb up to the fortune-teller's apartment, another step into their being drawn into the adult world of deception and disunion. Most symbolic of these up-and-down images is the casually cruel separation of the boys in prison into one up on the second floor and one down on the ground floor.

Up-and-down becomes so important in this film because that is the source of adult power. Simply, adults are taller and bigger than children. In scene after scene, Pasquale and Giuseppe are surrounded by men taller than they are. The men casually use that bigness to knock the boys around. The bully Arcangeli is taller than the other juvenile prisoners. The director of the prison (note his Fascist salute) towers over and bullies the kindly prison guard who cannot stand the cruelty of the prison. In short, the film becomes a study in power. Bigger wins. Might makes right (for example, in the newsreel of the war).

Shoeshine becomes, then, much more than a realistic picture of the harshness of life in Italy after World War II. It is that, surely, but it is much, much more. It is a bitter study of growing up (pun intended). It shows the way we humans can and do grow the easy friendship of children into the deadly enmity of adults.