This movie begins with an eye and ends with an eye. It's all about what you see and what the characters see. At first, we see things “objectively” and then, especially in her long, painful descent into madness, we see through the heroine's eye.

That eye is Carol Ledoux's (or Catherine Deneuve's). Her name means “sweet” (the first of many food metaphors in this film), and “doux” is just the word for Carol at the beginning. Deneuve's special kind of bland, seemingly colorless acting embodies that sweetness. Deneuve has kept this style to this day, even in her current grandmotherly roles. She is perfectly suited to enacting a woman in the world of this film, a world dominated by men.

Not just Carol, but the film as a whole makes a feminist outcry. The two Belgian women in Repulsion are trapped in a London dominated by sexually-driven men, men seeking penetration. Carol's sister Helene (Yvonne Furneaux) is used by her perhaps-married lover Michael (Ian Hendry). Colin (John Fraser) has fallen for Carol, and he seems decent enough, but Colin's friends, the white-collar louts in the bar, think of women as simply orifices to be used. And the whole beauty salon is devoted to making women palatable to men. Carol is both victim and victimizer with the landlord (Patrick Wymark) and with Colin. Yes, Carol murders two men. But she is a victim as well as a victimizer. They both may be innocent when they enter, but one violently forces his way into her apartment, and the other tries to rape her. Carol is both victimizer and victim (as, Ewa Mazierska point out, Polanski is himself).

This film is about sex—now, there's an extraordinary critical insight! Carol is grotesquely repressed sexually, or, more exactly, she has deeply ambivalent feelings about sex. She feels a mixture of desire and disgust at what she desires. She pushes Colin away, savagely wiping her mouth clean after he kisses her. Although she is disgusted by her sister's lovemaking and the lover's presence in the apartment, when Michael leaves an undershirt behind, she longingly smells it and lovingly irons it. As she becomes more and more insane, she has nighttime fantasies of being raped by Michael. Then in the finale—and this is Polanski's seeing and ours, not Carol's, who is out of it at this point—Michael stares lovingly at her as he carries her, confirming my suspicions that he's been lusting after her all along. But now, and only now, in her catatonia or death, she is at last held in the arms of the man she desires.

Most writers on this movie say she has this mad mixture of desire and disgust because she was molested by her father, and they give as evidence the final photograph. I'm not convinced. Carol fails to feel normal disgust at the rotting rabbit and potatoes or at Colin's body in the bathtub. She uses (improbably) a book to wipe Colin's blood off the door as if to say that words no longer mean anythng to her. In the childhood photograph, she looks schizoid or schizophrenic, and she is certainly schizoid in the first part of the movie. Her indifference to food also suggests schizophrenia. Carol seems to me your basic schizophrenic, possibly innately so or because of childhood abuse (suggested by the photo). Her adult sexual repression or fear of men, androphobia, might suggest sexual molestation in childhood, but only might. Not all molested children become schizophrenic (in fact, very few, I suspect). And not all schizophrenics have been molested.

Polanski lards his film (pun intended) with food images throughout: Helene's cooking, her dining with Michael, Colin's taking Carol from one restaurant to another for lunch, Carol nibbling sugar cubes, or the wine bottles Michael brings back from his trip with Helene. Then, of course, there is the famous rabbit. Is it a predecessor to the notorious boil-a-bunny scene in Fatal Attraction? Who knows? At the very least, it suggests a foetus, particularly when Bridget glimpses its head in Carol's purse. And it may remind us of the “rabbit test” for pregnancy. A psychoanalytic critic would point to oral themes: food, disgust, confusion of boundaries. And these are consistent with schizophrenia.

Another pervasive image Polanski provides is space. Gilbert Taylor's brilliant, expressionistic camera work and, in particular, the sound track play extensively with space. Often the film defines space exterior to the apartment by sounds: the bells of the nunnery, the spoons played by the buskers, distant sounds of the elevator in the apartment building or a piano or a telephone ringing, voices, footsteps, and so on. The sounds of Michael and Helene making love in the next room turn into Carol's nighttime fantasies of being raped by Michael. As the film goes on, Taylor uses special lighting to create deep shadows and wide-angle lenses to expand the space of the apartment in grotesque ways. It collapses down to a normal view when Helene, Michael, and the neighbors enter the apartment. They see things normally and, at that point, we do.

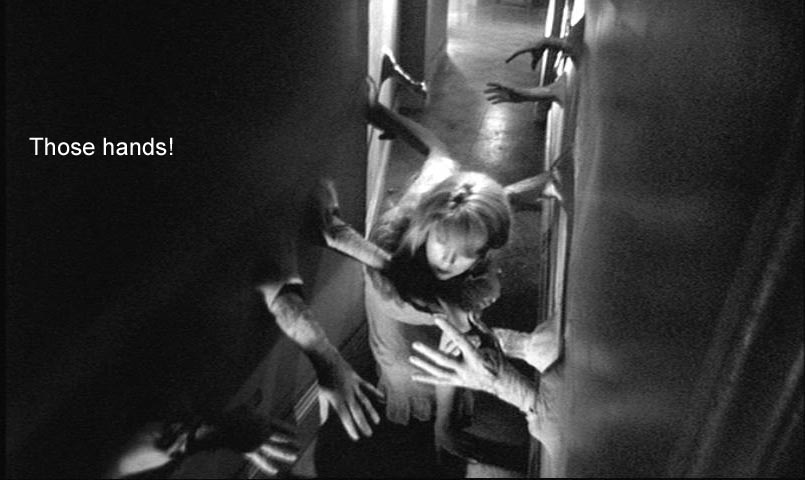

Space in this film exists to be broken into and through. The first words of the film set the pattern: “Have you fallen asleep?” intrudes the exterior reality of the salon into the interior of Carol's dreamy mind. Later, Carol stabs her client in the beauty salon, breaking the barrier of skin as she does with the landlord. She breaks into Colin's skull. The sounds from outside penetrate the apartment. Carol is fascinated by the crack in the sidewalk, and later, the walls of the aparment spontaneously crack open. Hands reach through the walls caressing Carol's breasts. Food fits this context; it goes from outside to inside.

Now, perhaps we are in a position to understand the presence of three quite odd bits, which are not part of Carol's madness. They are “objectively there.” In one, Bridget (Carol's buddy at the beauty salon [played by Helen Fraser]) recalls the eating scene from Chaplin's The Gold Rush in which Charlie turns into a chicken in the eyes of his starving companion, and Carol laughs for the first and only time in this picture. This bit of business is the easiest to understand. It introduces yet another eating metaphor. That scene from The Gold Rush, like Repulsion, projects the characters' interior thoughts into visible objects on screen. To me, this bit embodies the central theme of this film, projecting, but more than projecting, converting the world into one's interior thoughts.

The other two “objective” oddments are the buskers playing the spoons and the nuns playing in their yard. They define the apartment, the buskers on the street side, the nuns on the courtyard side. Both seem somehow archaic and ancient, as opposite to the ‘sixties world of Helen and Carol. They are opposites, one male, one female (emblems of the sexual opposition of this film). Both are sexless (unlike Carol's sexually turbid world in which every object is sexually charged). And both are playing, something Carol cannot do. What she sees, she sees as deadly serious and threatening.

Play implies boundaries and limits: you have to say that you will go no farther than this in attacking your opponent. Carol's world has no such limits. Her inner world bursts out from her, penetrating and changing the outer world. As one of the film's marketing slogans crudely puts it: The nightmare world of a virgin's dreams becomes the screen's shocking reality!

Could we say then, that the central idea that shaped this film, is penetration, violent penetration? That it acts out Polanski's peculiar mixture of feminist values and fantasies of sex as rape? The outer, material world breaking into the inner world of thoughts and fantasies? And that inner world changing what we perceive as the outer world? Cracking the boundaries between inner and outer reality? I'd settle for that.