There is a curious symbol in this film—at least I think it is a symbol. The fishnet: a mesh net attached to a loop of wire at the end of a long pole. One would use it to capture something in the water. M. Hulot (Jacques Tati) has one sticking out of the trunk of his car and conspicuously carries it into the lobby of the Hotel de la Plage. The children all carry them. A variety of adults do. There are some stacked in the hotel lobby. We see fishnets again and again in such a variety of settings that I think it is more than just a recurring image. It's a symbol. But of what?

I find it hard to read a farce like Les Vacances de M. Hulot. Feature films mostly have plots in which there is a logic to events. A leads to B which causes C, and so on. But farce is different. Farces like this film just string along a series of gags. One could change the order or one could add or subtract gags from the series without really changing anything. Nevertheless even in so formless a film as this, one can find a texture of jokes, a pattern.

As always, I suggest looking at the opening and closing shots. The opening shows an old boat at the water's edge. Probably, it is not even seaworthy. It is followed by the first gag, clumps of passengers running from platform to platform while the loudspeaker in the train station squawks meaninglessly. Then we see M. Hulot's ancient car (an Amilcar from the '20s) sputtering along, being passed by swift modern vehicles. A great many of the gags in this film have to do with transportation: the train station; the bus to the resort (Saint-Marc-sur-mer in Brittany); cyclists turning to look at Martine (Nathalie Pescaud); the boat that slides into the water; the kayak that enfolds M. Hulot like a sea monster; the disastrous horseback ride (or non-ride); the man trapped in the rumble seat; or the cavalcade for the picnic.

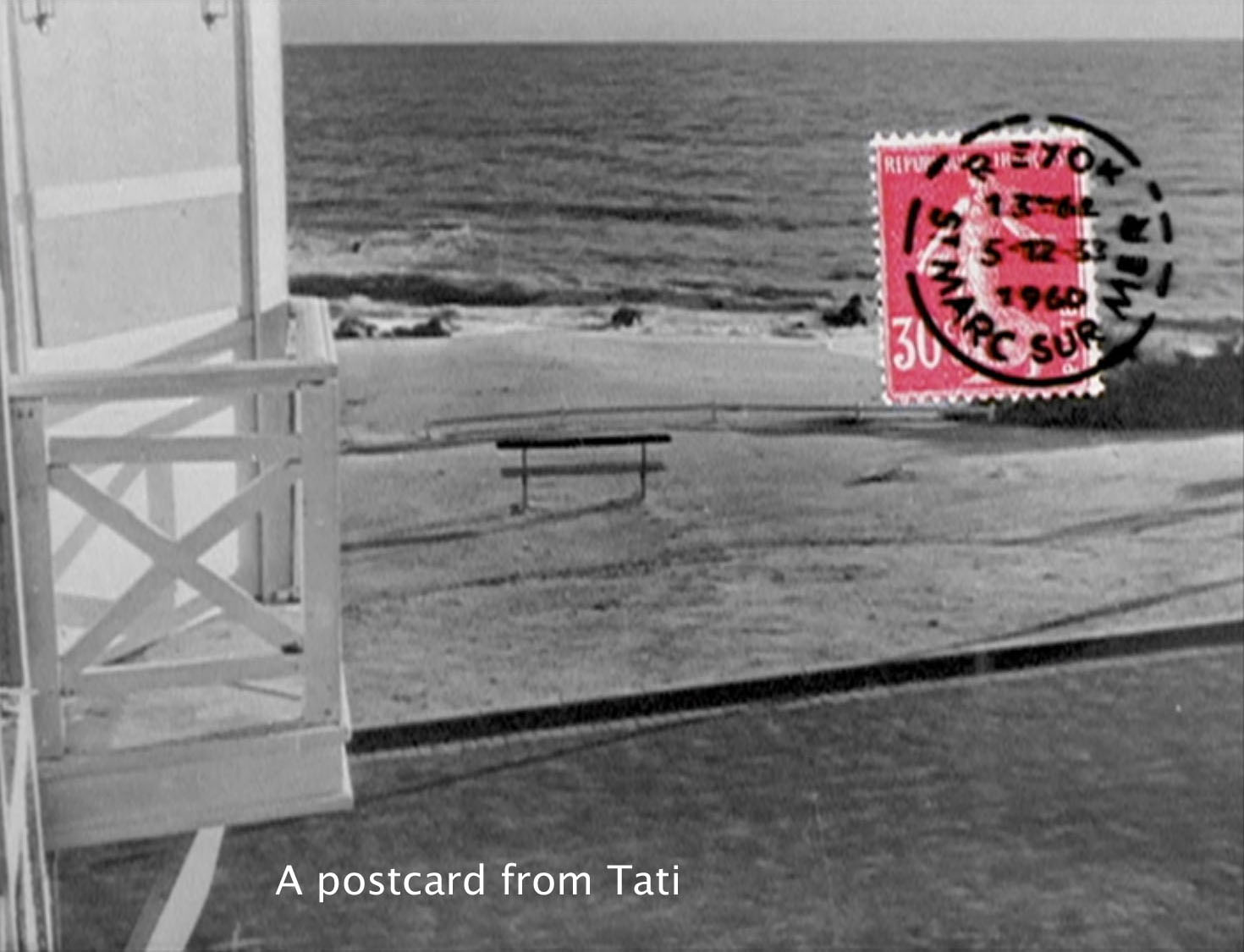

The final shot also has to do with transportation. Tati cuts from Martine's balcony overlooking the beach to M. Hulot's car, which putt-putts out of the frame. Then flashes on the screen a red postage stamp postmarked for Saint-Marc-sur-mer. No doubt, Tati is referring to his first feature with its postman hero, but he is also mailing his film to us, as if he were sending a postcard from a beach resort (as he is) in the film's final act of transport.

In the train sequence, the hotel's clients frantically rush to get there, but, once there, they sit in the lobby and do the same things they would do at home. Hulot arrives on a beautiful summer day. But the Commandant (André Dubois) is yammering in the lobby about his war. The card players are playing cards. The radical young man is reading his radical newspapers. Mr. Schmutz (Mr. Mudd?) carries on his business deals. One elderly couple endlessly (Marguerite Gérard, René Lacourt), pointlessly strolls.

Basically, the film builds around three groups of people, three types, each contributing in its own way to the merriment. There are the workers: the waiter (Raymond Carl), the hotel owner (Lucien Frégis), and the ice cream man. They plod on with their daily routines, vaguely hostile to the interruptions and confusions caused by the guests, especially Hulot.

Then there are the stodgy people in the hotel who seem to be living their ordinary city lives instead of enjoying the beach. As opposed to them, there are the people who are there determined to have fun and who do have fun. The children, obviously (and throughout the film we hear children's joyful voices on the sound track). Hulot, obviously—he tries everything and is unfailingly courteous and helpful to one and all, trying to create a happy time for everyone, although, of course, everything he does turns into chaos. There is the British games lady (Valentine Camax) who supervises the tennis and enjoys everything. At the end of the film, we learn that the poor, dominated man of the strolling couple also had fun watching Hulot.

And then there is Martine, who smiles benignly on everything, especially Hulot. He amuses her without arousing any amatory interest. She has a special status. She is the object of men's desire. We are made aware of her flesh, in her bathing suit, in the short shorts she wears for the horseback riding, and especially in one intimate moment at the masked ball. When they dance, Hulot shies away from touching her naked back and coyly rests his fingers on her neckband. While the other characters are caricatures, she is real. She plays a record, and it becomes the theme music, as if she were in charge of the film. I think she stands for us. She is bemused by the goings-on, as we are. She models our response for us.

The other guests, however, resent Hulot for introducing novelty into their routines, and they make their annoyance very clear in the finale when they snub him. Like the workers, instead of enjoying the beach they stick to their routines.

For the vacationers on the beach, simple sea and sand are not enough. They tangle with boats, trains, kites, cameras, telephones, cabanas, and especially automobiles.

Highly conventional people, the guests at the hotel end their vacation by insincerely taking addresses, making plans to meet, and so on. By contrast, Tati's final shot shows us the eternal things, wind, waves, sand, sea. In a touching moment leading into the finale, a mother has to drag her little boy away from the sea to go back to the city. He had fun, even if she didn't. The vacationers clung to their usual objects and concerns, especially all the things we use to move ourselves from place to place: trains, buses, cars, boats, or horses. They fail, especially in Hulot's hands, causing trouble. Think of the final, over-the-top chaos he causes with the fireworks. The sea and the sand stay put. They are calm. They endure.

On one side, we have the transience and brevity of this beach holiday. We see its beginning and its end. But on the other, we have the first and last shots. We see the sand and the waves—they last. In between we see these groups of people responding in their various ways to the circumscribed French August "vacances." The basic contrast in the film is between the sea that ceaselessly, rhythmically flows and our human tendency to cling to habits and devices, especially the habit of rushing here and there.

In a sense, the fishnets symbolize this, which I see as the ultimate tension in the film. The essence of the device is that it does not hold on to the water. That flows through, and we never see anything captured in the fishnets. Experience, the time of a vacation, escapes us. It is as elusive as this string of les gags so wonderfully assembled around the figure of Hulot. It is ironic that, as a tribute to this film about the passing of all things, the town of Saint-Marc-sur-mer should have put up an ever-so-permanent statue of Mr. Hulot overlooking the beach he made forever famous.

Enjoying: Many critics have pointed out that Jacques Tati's genius lies in making carefully planned deliberate, calculated "gags" seem artless. I have a lot of fun playing with the DVD of this film, going through one or another gag in slow motion so that I can see Tati's marvelous attention to detail, notably, facial expressions, small movements of hands or legs, particularly legs, the background, where often something is happening that you would not otherwise see, and, of course, the sound track.