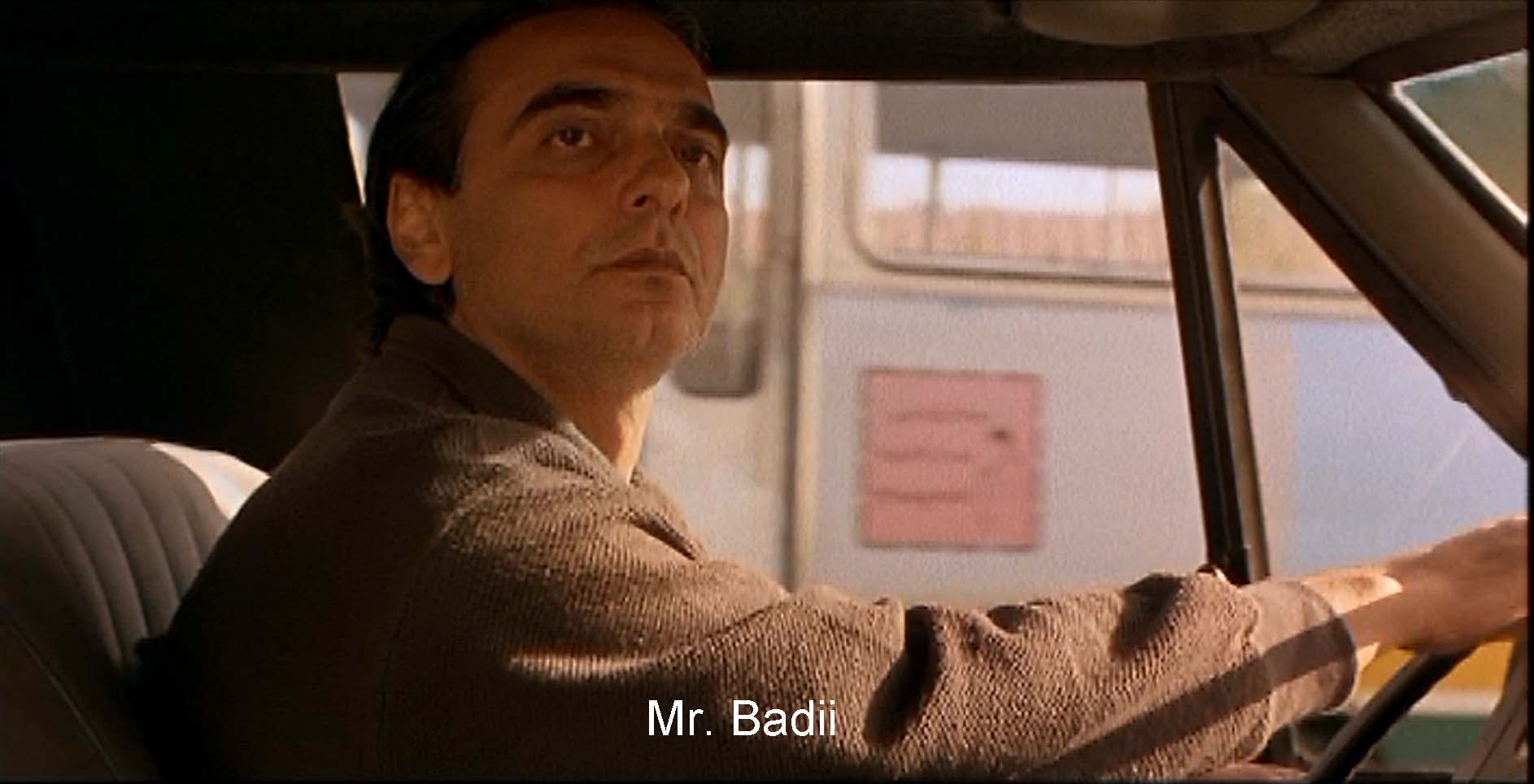

The first word in Taste of Cherry is “Laborers,” and that, to me, is the key that opens this film up. The bulk of the film shows a middle-aged, gloomy-looking Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi) driving around and around a great hill of sandy dirt, the sound track gritty, the images tan and brown, in short, dirt-colored. Unlike the people he talks to, or the people who talk to him, he does not work. He is an idler.

But he, like other of Kiarostami’s heroes, one, has a desire that drives him, and, two, he needs others to help him. The others in this film simply want to work.

Badii is well-to-do. He drives a Range Rover. He has a nice apartment. He has enough money to pay a volunteer amply for filling in the hole he has dug in that huge mound of dirt that he is driving around. We learn in the course of the film that Badii has (or had) a son. He does not work. Instead, he drives around looking for someone to help him in a self-negating task. That’s all we know about him.

Like other Kiarostami characters, he is driven by a desire, and Kiarostami masks that desire. We don’t find out what it is until well into the film. At least one of the people he asks to help him sends us on a false trail. Finding out what he is up to is our desire.

Work, it seems to me, constitutes a major theme in this film. (I can’t get out of my mind a fourteenth-century jingle: “When Adam delved and Eve span / Who was then the gentleman?” The rhyme was a product of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 [see Shakespeare’s 2 Henry VI]. In the beginning, when Adam dug and Eve spun, when everybody worked, all men were created equal. There was no upper class of idlers like Badii.)

I think Kiarostami here plays on the same Garden of Eden idea, although this grim landscape surely represents the earth after the Fall of Man. Adam’s curse is that people have to work and die. A “security guard” describes this environment as “nothing but earth and dust.” “We all have our responsibilities,” he says. “I can't leave my post.”

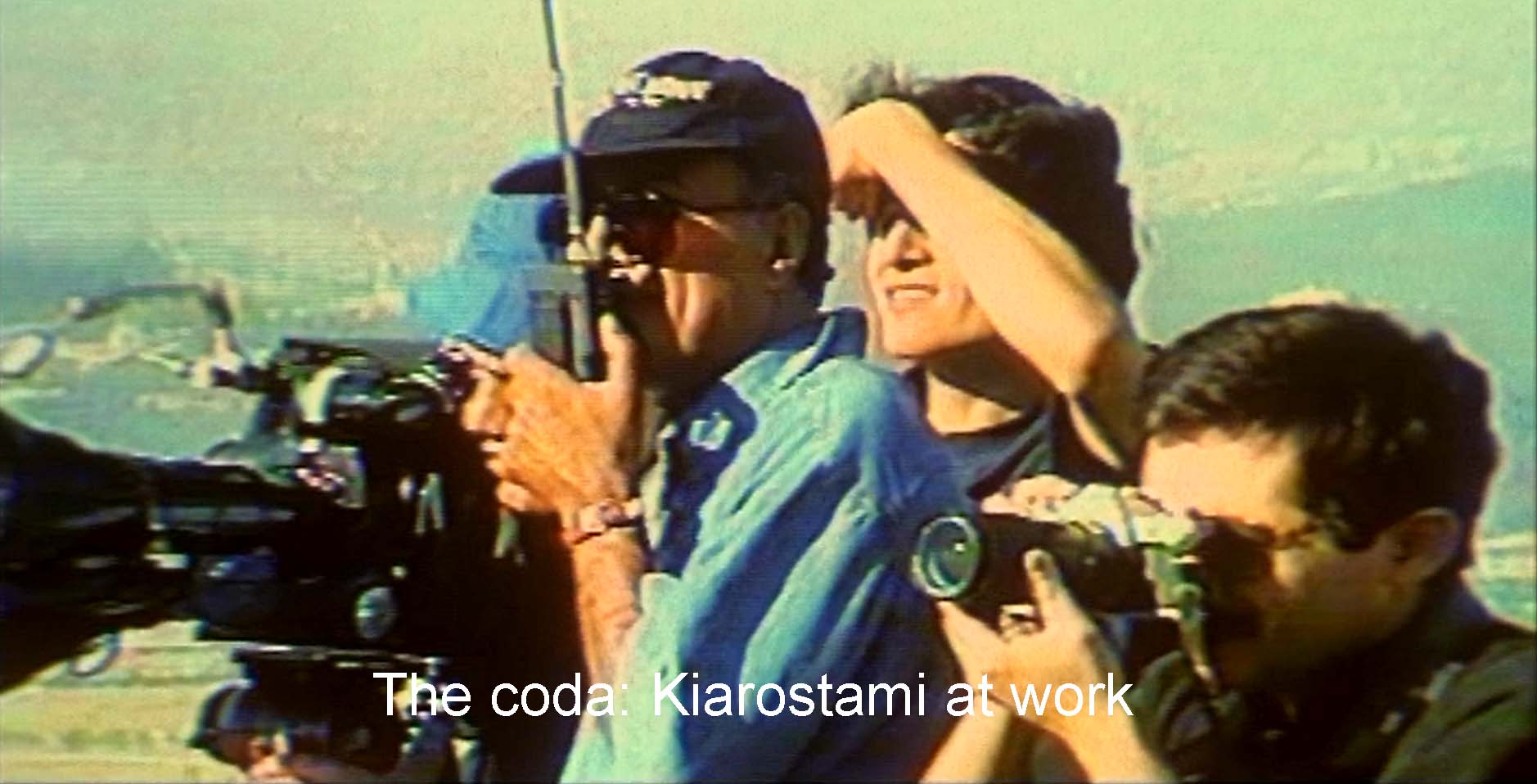

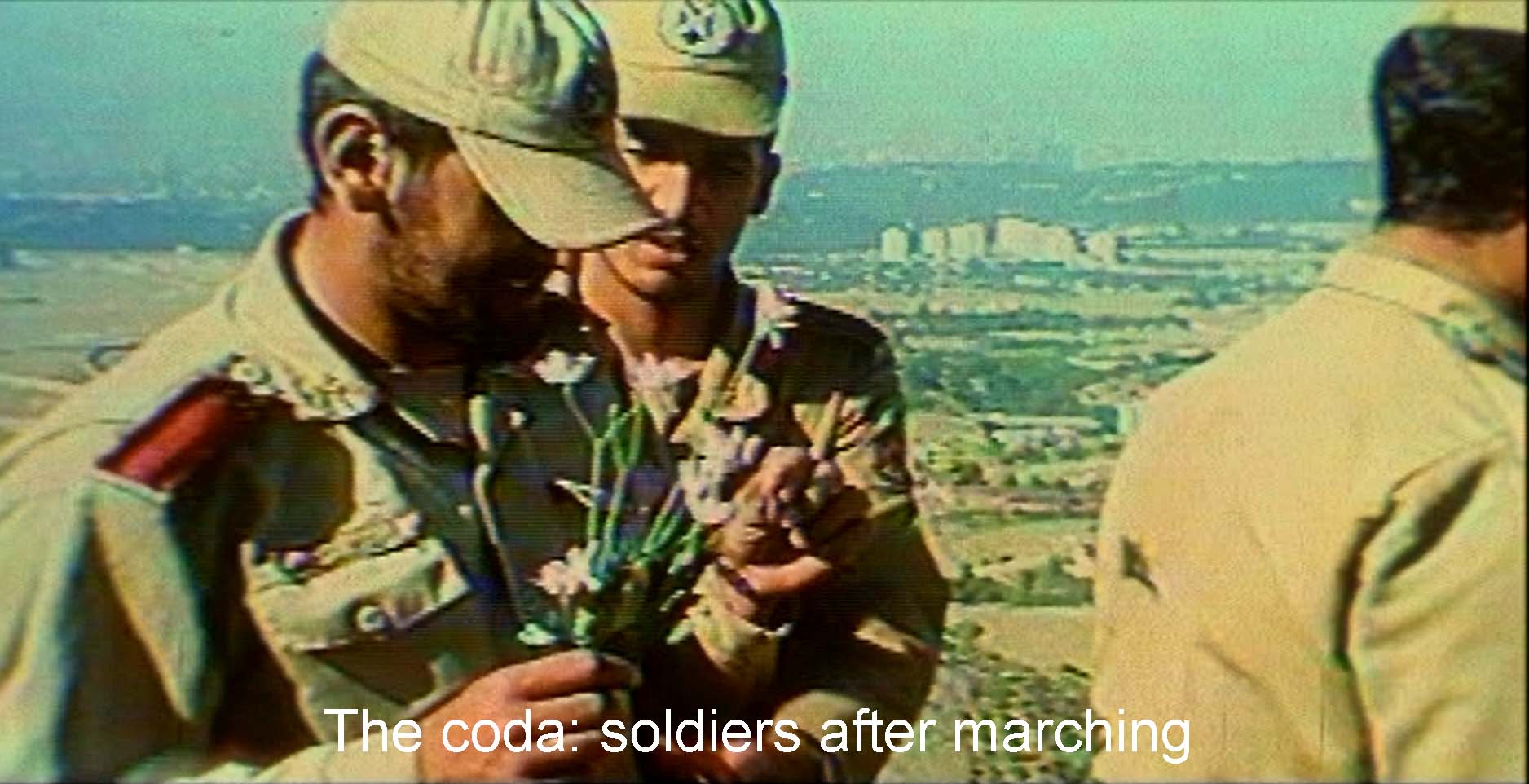

Everybody works in this film, everybody but Badii. We see a man spraying with a hose, a man arranging a deal on the phone, students running in phys-ed, machines dumping and sorting rocks. We even see children playing in a rusted-out car, play being (proverbially) children’s work. Badii drives a front wheel of his car over a cliff, and a group of green-shirted workers enthusiastically pull the car back onto the road. (They wear just about the only green we see until the finale).The contrast carries over in the “coda” to the film. Suddenly, after all the dirt and the dun-colored images, Kiarostami shifts to a totally different landscape, bright green, and filmed in video, so that it seems blurred and completely different from the previous scenes. Soldiers are marching double-time, and Kiarostami is filming them. Critic Jonathan Rosenbaum notes that shifting to the soldiers reminds us of what Badii told us was the happiest part of his life. A tree in full bloom suggests life, but a tree is also where one of the characters almost hanged himself. And Louis Armstrong plays “St. James Infirmary.” There is always death, but even death is beautiful.

Nothing is simple. We need to think—to work at this film..

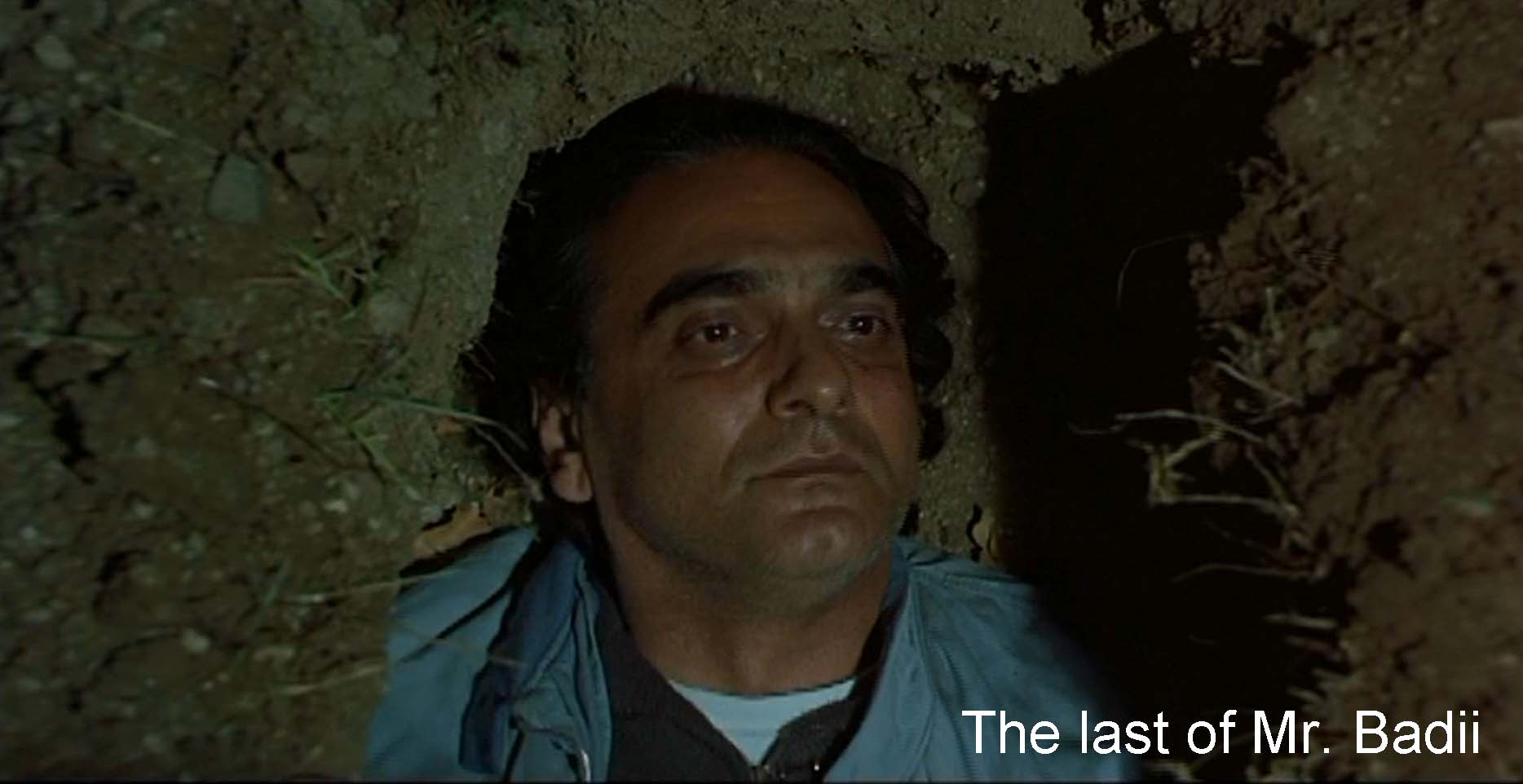

The coda itself portrays work. We see Kiarostami filming the scene we have earlier seen of the soldiers marching double-time, counting and shouting. (One of the words they shout is “Revolution,” another kind of effort, another statement of the symbolic value of the soldier Badii talks to, and, probably, a sop for the authorities.) While Kiarostami films, Badii, not a professional actor but an architect and friend of Kiarostami’s, still idles. He walks around aimlessly and offers Kiarostami a cigarette. In a sense, work, Kiarostami’s work anyway, turns the whole world green. Badii, by contrast, achieves nothing. The last we see of him in the story, he is lit by lightning, staring at the moon, a sacred fool like Pierrot..

This film has two dominant images. One, obviously, is the car. Badii sits in his car, driving and talking, isolated from his fellow human beings. He gets out a couple of times, but gets back in again. Not only does he not work, he is essentially isolated from those who do by being in his car. Kiarostami emphasizes that isolation by cutting back and forth from close-ups of Badii in the car or the person he is talking to and long or aerial shots of the great hills of dirt that make up the mountain Badii is driving around.

That grim, sandy desert is the other dominant image. We see huge earth-moving machinery at work moving tons and tons of dirt and making tons and tons of cement. The gigantic machines make a sharp contrast to Badii’s white car and his selfish little hole and his frustrated efforts to get someone to fill it up for him. The bright green landscape at the end makes a different contrast. There, the soldiers rest after their run, and one picks a flower. Kiarostami films. Work makes life livable—green and viewable—tv style.

Badii tells the people he wants to shovel for him, Don’t think about the job, think about the pay. But the people care very much about the job. They worry about it at length. Badii’s own dislocated values lead him to misunderstand other people’s motivations. (Incidentally, so far as I have been able to find out, the pay he offers, 200,000 tomans was worth about $1500-$5000 U.S.)

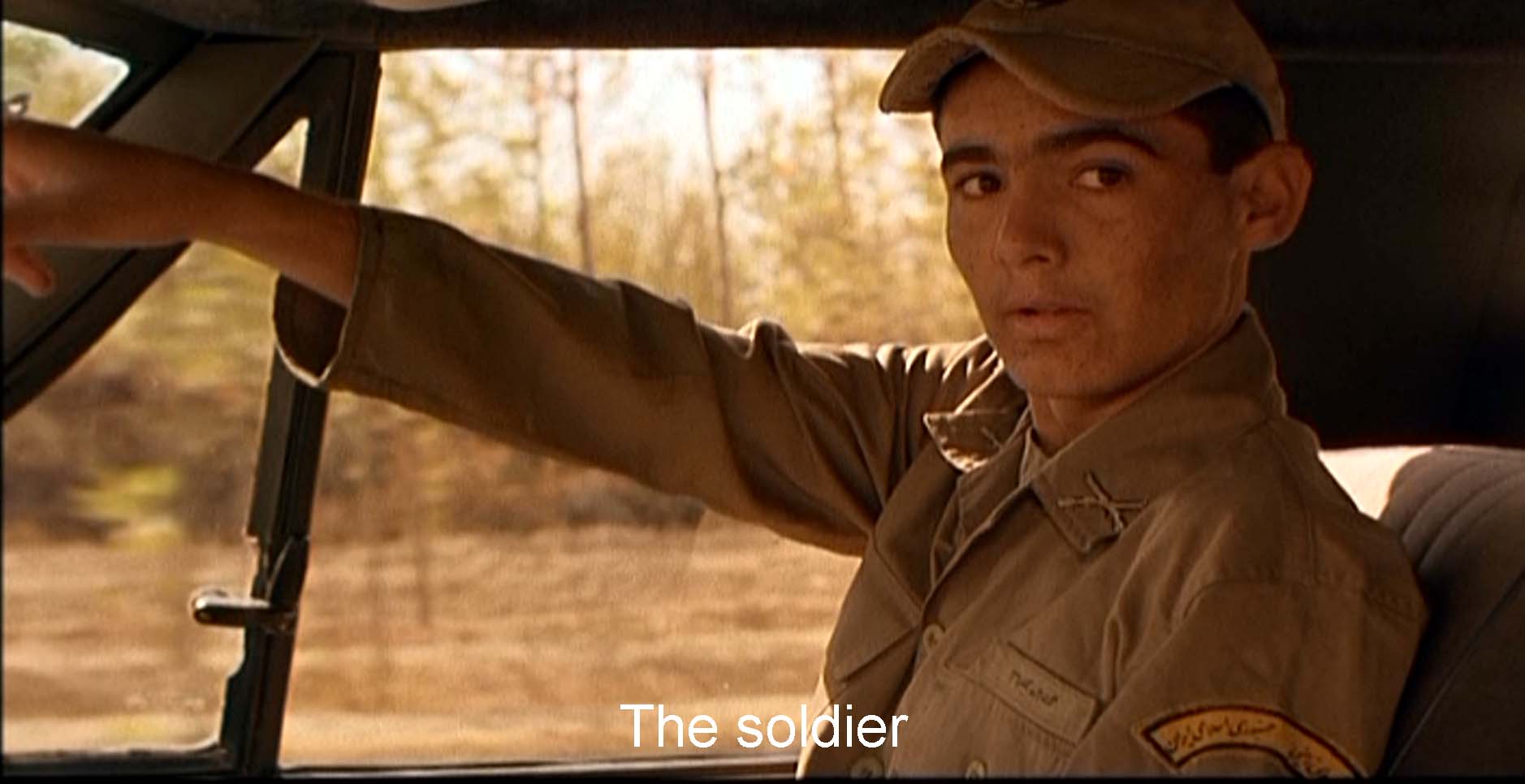

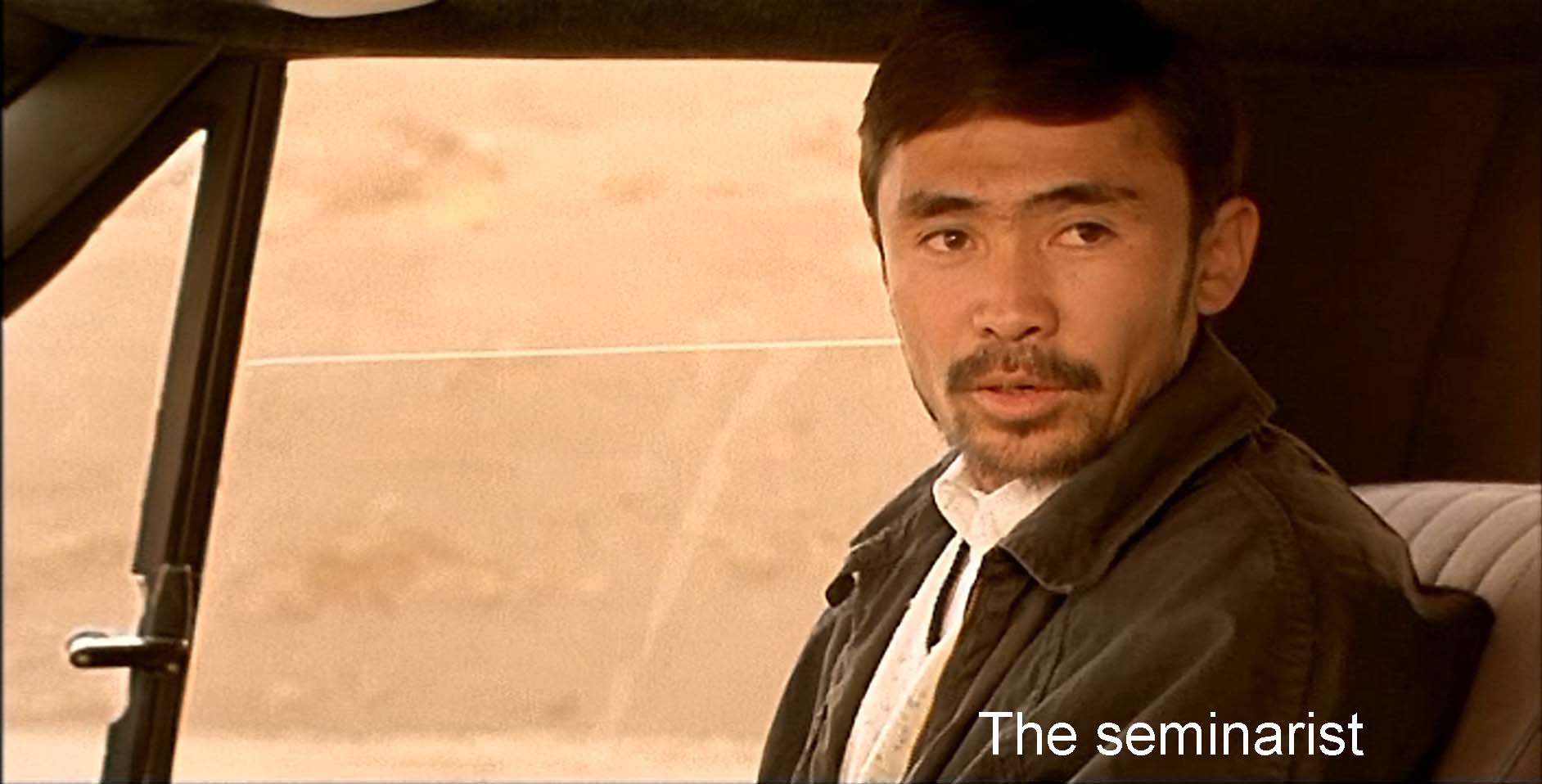

Trying to find someone to do what he needs done, he picks up three people in his car. All three he meets along the road. Two are headed for work; the other is reading. They have vital purposes. He does not. Kiarostami often uses the road and traveling metaphorically as “the road of life.” Here the road marks Badii’s purpose, cancelling life, contrasted to the fulfilling purposes of the three people he picks up.

The three have different nationalities. The first, the soldier (Afshin Khorshid Bakhtiari), is Kurdish. The second, the seminarian (Mir Hossein Noori), is Afghani. The third, the taxidermist (Abdolrahman Bagheri), is Turkish or Azeri (I can’t tell which). Kiarostami is always interested in people's being displaced—in the wrong place or the wrong occupation (work). For example, the soldier is really a farmer. The seminarian should be studying in Afghanistan, but has been displaced by the war there. The film makes several references to wars in the region, another kind of work.

We can easily read the three symbolically. The soldier surely points us toward nationalism and patriotism. Ironically, “a soldier's work is killing,” but this soldier is afraid to bury a dead man. The seminarian represents a religious point of view. He describes his work as “to preach and guide.” He is on his way to keep a lonely fellow-countryman company. The third, a taxidermist, works at a natural history museum. He could represent the natural sciences, a natural pairing-off with the religious seminarian. Like the seminarian, the taxidermist teaches. His job is to kill (in this instance, quail) and then, for the museum’s dioramas, to bring them back to life by his art or at least to an imitation of life. In a way, he is like the filmmaker who also captures and freezes the living and who also creates from them an imitation of real life. This film revolves around a puzzle: why does Badii want what he wants? The natural history museum provides an answer when religion (seminarian) or nationalism (the soldier) does not. The taxidermist, the materialist of the three, agrees to do what Badii wants to provide money for his sick son. He adapts Badii's desire to his own desire. And that’s life.

Kiarostami filmed the three conversations in the car by a curious tactic. In each, Kiarostami took the place of the person being spoken to. If the camera showed the soldier or the seminarian or the taxidermist talking to Badii, Kiarostami was in Badii’s place in the driver’s seat doing Badii’s half of the conversation. If the camera showed Badii, Kiarostami was in the passenger seat doing the talking for the soldier or the seminarian or the taxidermist. You could say that the exigencies of filming in a car explain this tactic. But it seems to me it gives these conversations a disjointed feel, emphasizing Badii’s isolation like the long shots of the landscape.

We humans live in a big, wide world, but Badii just keeps circling around that dirt pile. Most of the film juxtaposes close-ups with long shots including aerial shots of the car. But no matter how far the camera strays from the speakers, the dialogue always stays loud, a further disjointing effect.

Kiarostami is playing with one of his favorite themes. People are driven by desires. Badii has his desire, and his three interlocutors have theirs. And we, the viewers, have ours. We want to hear that dialogue, and we want to see those close-ups. We want to know what Badii is up to, a desire fueled by Kiarostami's misdirection. We do not find out until the conversation with the soldier. We are puzzled by the gap in the taxidermist's first appearance. Kiarostami demonstrates our desire to us by seeing the world outside the car through the screen of its windows. Later we see the world from a watchtower and the windows of a museum workshop. We see the outside of Badii’s apartment, but we are not allowed the inside. And, of course, we are seeing all this through the screen of the film.

Kiarostami frustrates us by never telling us what happens to Badii. Instead, Kiarostami gives us that peculiar coda in the green landscape. That, too, frustrates us by its inferior picture quality. We want to see, but we have trouble seeing.

We want to know the motive for Badii’s quest, but Kiarostami never tells us. He says to the seminarian, “It wouldn’t help you to know and I can’t talk about it and you wouldn’t understand. You can’t feel what I feel.” “You comprehend my pain but you can’t feel it.” Frustrating! Jeffrey Cheshire makes the interesting suggestion that perhaps Kiarostami conceals Badii’s motivation, because what Taste of Cherry really concerns is the existential anxiety, bluntly stated by Camus to be the only philosophical question worth asking is: Why go on living at all? Why should Badii, or anyone, want to live in this world? After all, the world the bulk of the film shows us is a grim desert where all do dirty, suffocating work. Only in the fantasy work of movie making is the world green or are there flowers and singing. The taxidermist reminisces: “I wanted to kill myself,” but then he started eating from a mulberry tree, and that changed his mind. Now, he tells Badii, Your mind is ill. “You want to give up the taste of cherries?”

Kiarostami, always subtle and ambiguous, never tells us what happens to Badii—except that the man was someone acting in a movie. One throwaway line about the taste of cherry gives us the title of the film and, ever so briefly, its theme. Desire and the objects of desire, even frustrated desire!, are what make life worth living. As the taxidermist says, “You have to change your outlook and change the world.” The movie and our desire to see it and understand it answer the question the rest of the film poses, Why live in a world of earth, dust, and endless work? Talk cannot say why we should want to live. Only desire, our desire, our drive, our love, as viewers of movies. That can make the world green and flowered and fun. I think that’s an amazing turn of this movie on itself.