Some don’t like Aparajito (1956) as much as Pather Panchali (1955), the first film in the Apu trilogy. Here, I think Ray combines the endearingly neo-realist style of Pather Panchali with some more conventional cinematic moves. He was more experienced as a filmmaker when he made this film, having already completed that first venture into directing. I think those who don’t care for Aparajito are reacting against a more conventional style of moviemaking in the later film.

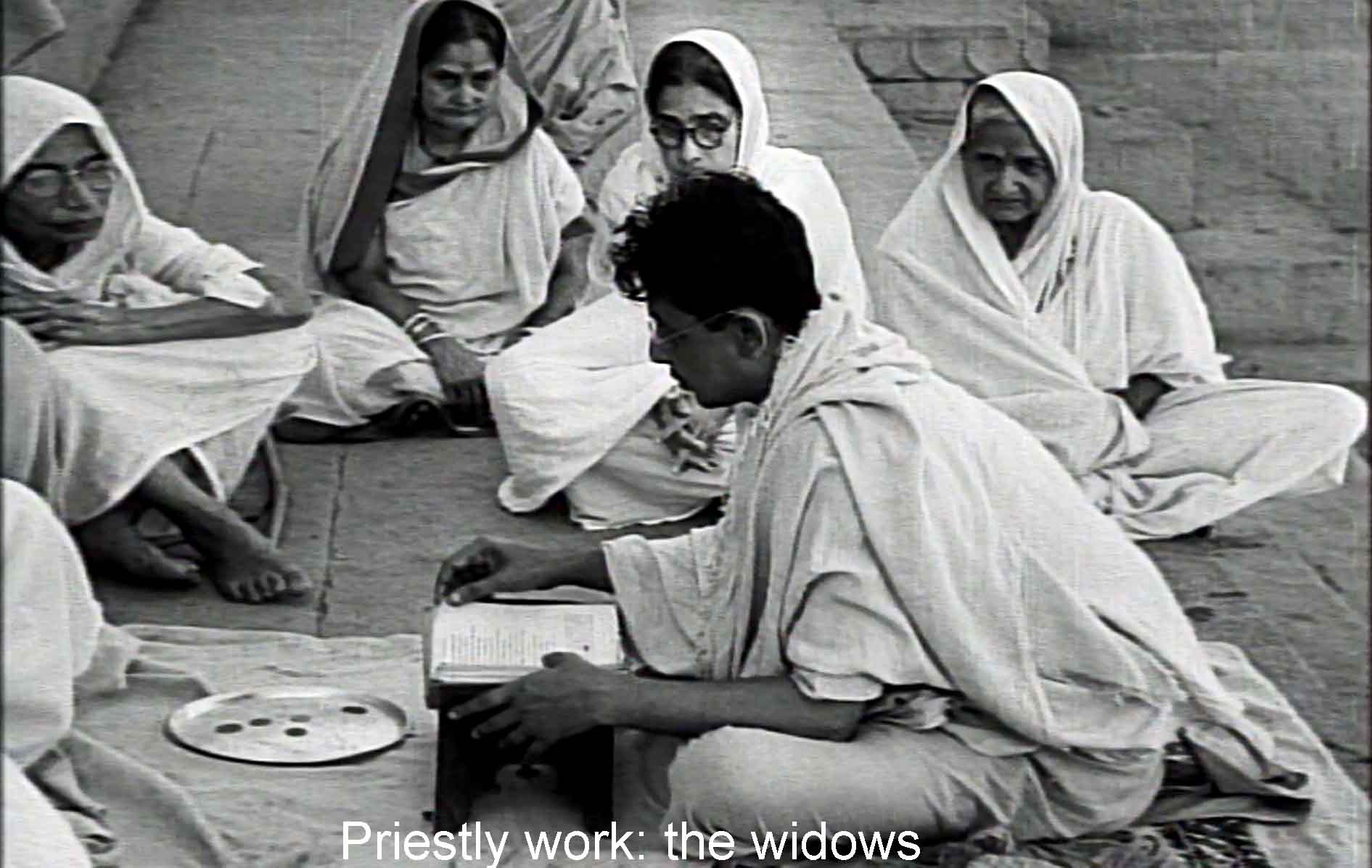

Be that as it may, Aparajito has a straightforward plot. It is now 1920. Impoverished, the Ray family has left its village home and traveled to the holy city of Benares (or today Varanasi). There the father Harihar (Kanu Bannerjee) makes a living as a priest performing various services on the ghats, the stairs that lead down to the sacred river, the Ganges.

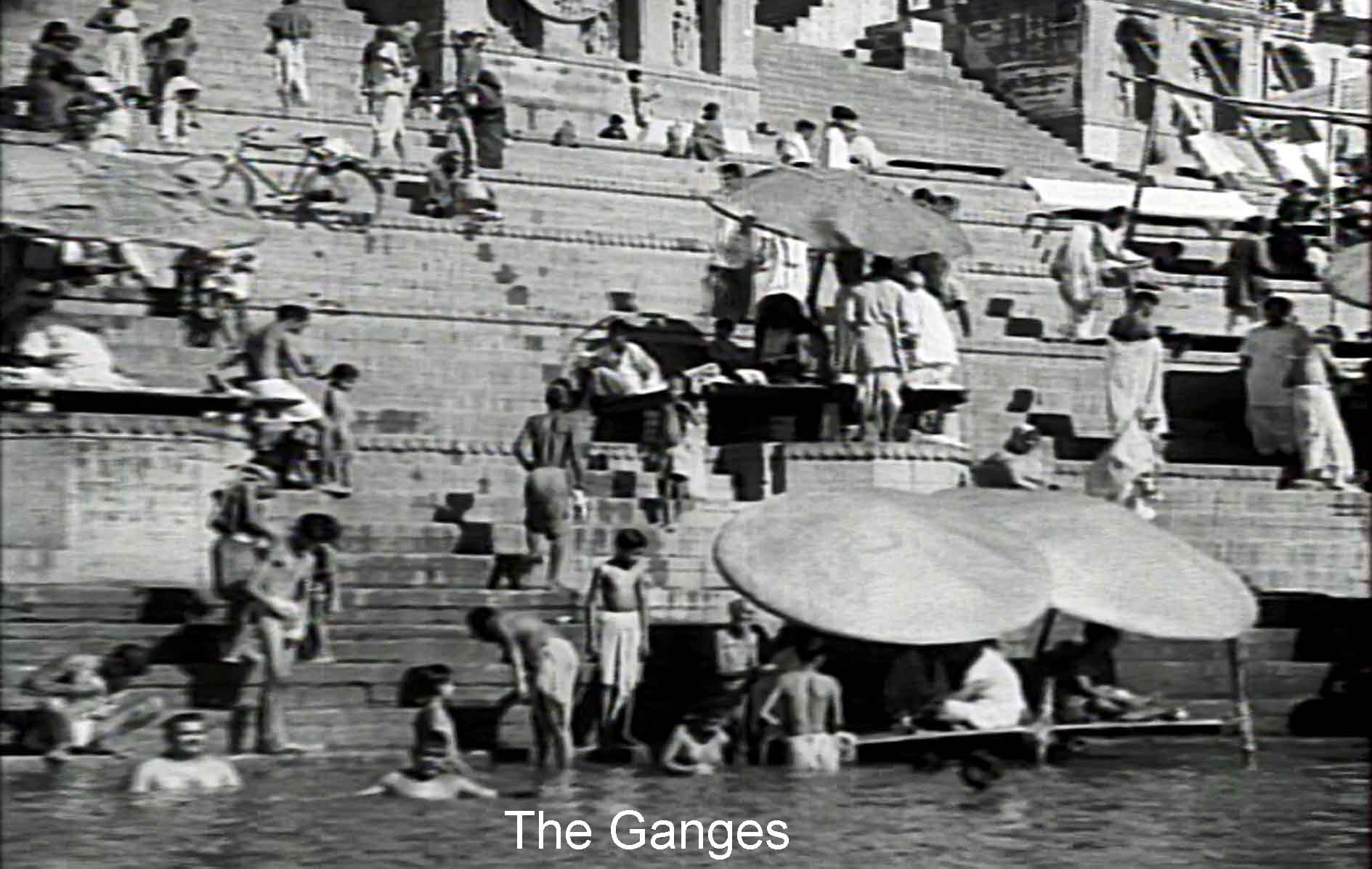

When I saw the Ganges in 1980, I thought it the dirtiest river I had ever seen. It is ranked, I read, the fifth most polluted river in the world. Yet Ray gives us a panorama of people dousing themselves with it, bathing in it, washing their clothes in it, swimming in it, even drinking it. The priest-father Harihar takes a canister of it and follows a ritual of sprinkling drops of the holy water through the open windows of houses that he passes. Ray is at his neo-realist best filming these goings-on at the river. Many of them we see through the boy Apu’s eyes, perception being one of Ray’s themes.

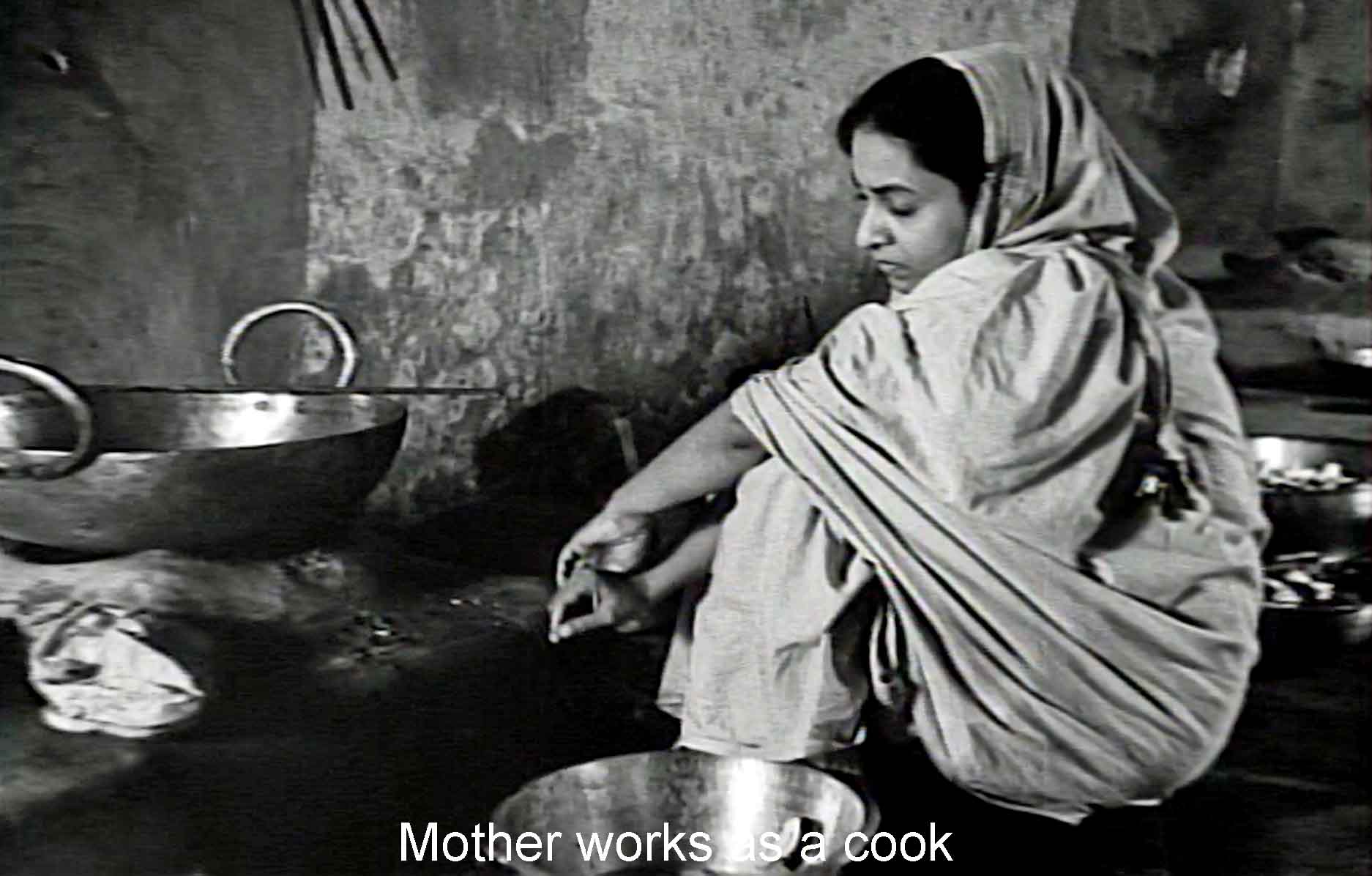

These shots of the Ganges also set up one cluster of values: family, bodies, religion, tradition. In that vein, the film shows us the Ray family’s life in the holy city of Benares. The mother Sarbajaya (Karuna Bannerjee) seems confined to cooking and cleaning in their not-very-private apartment. We see the father Harihar conducting priestly rituals and inviting strangers to tea (prepared by his overworked wife). We see the boy Apu (Pinaki Sengupt) running wild on the streets—motion recurs again and again in Aparajito.

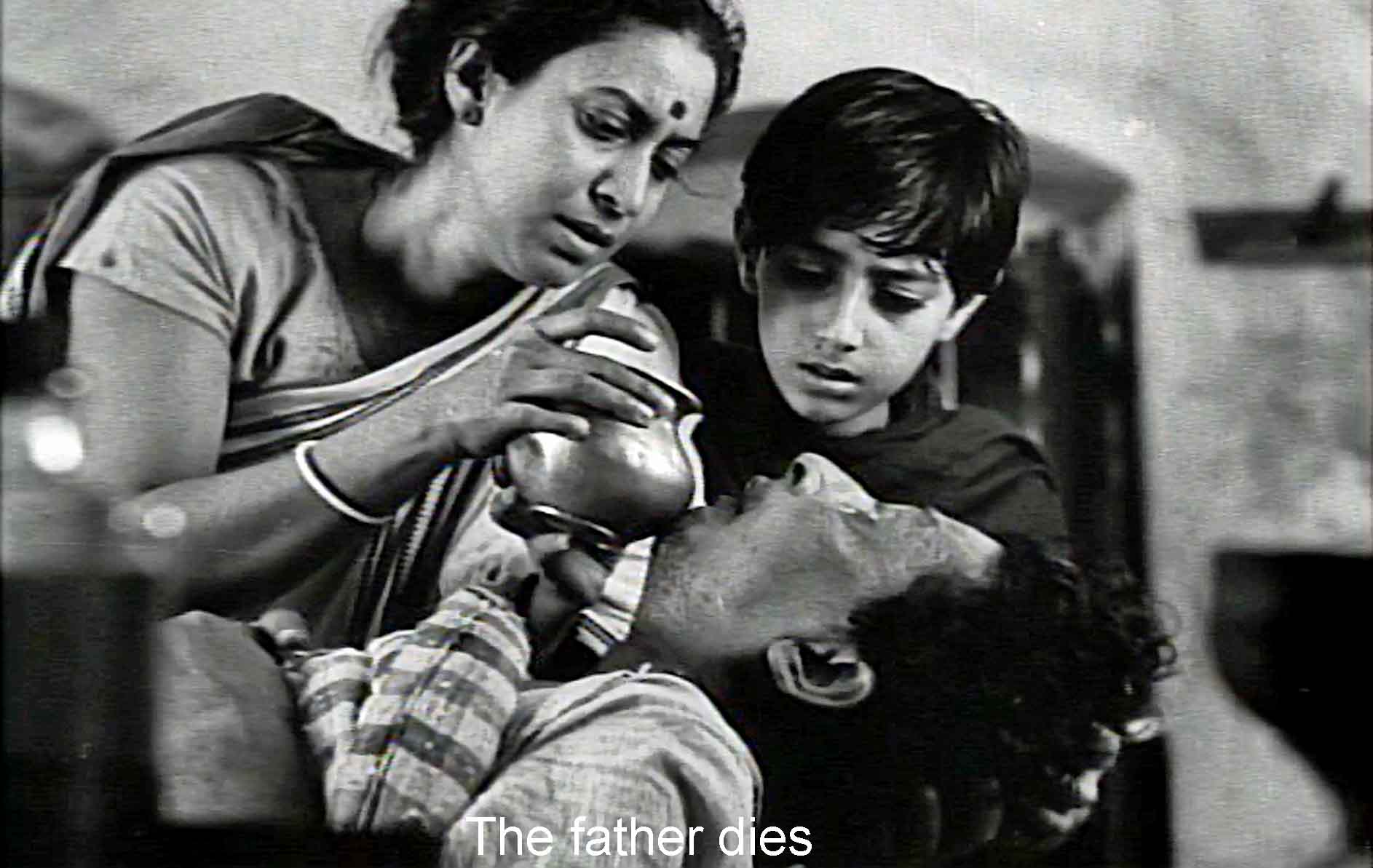

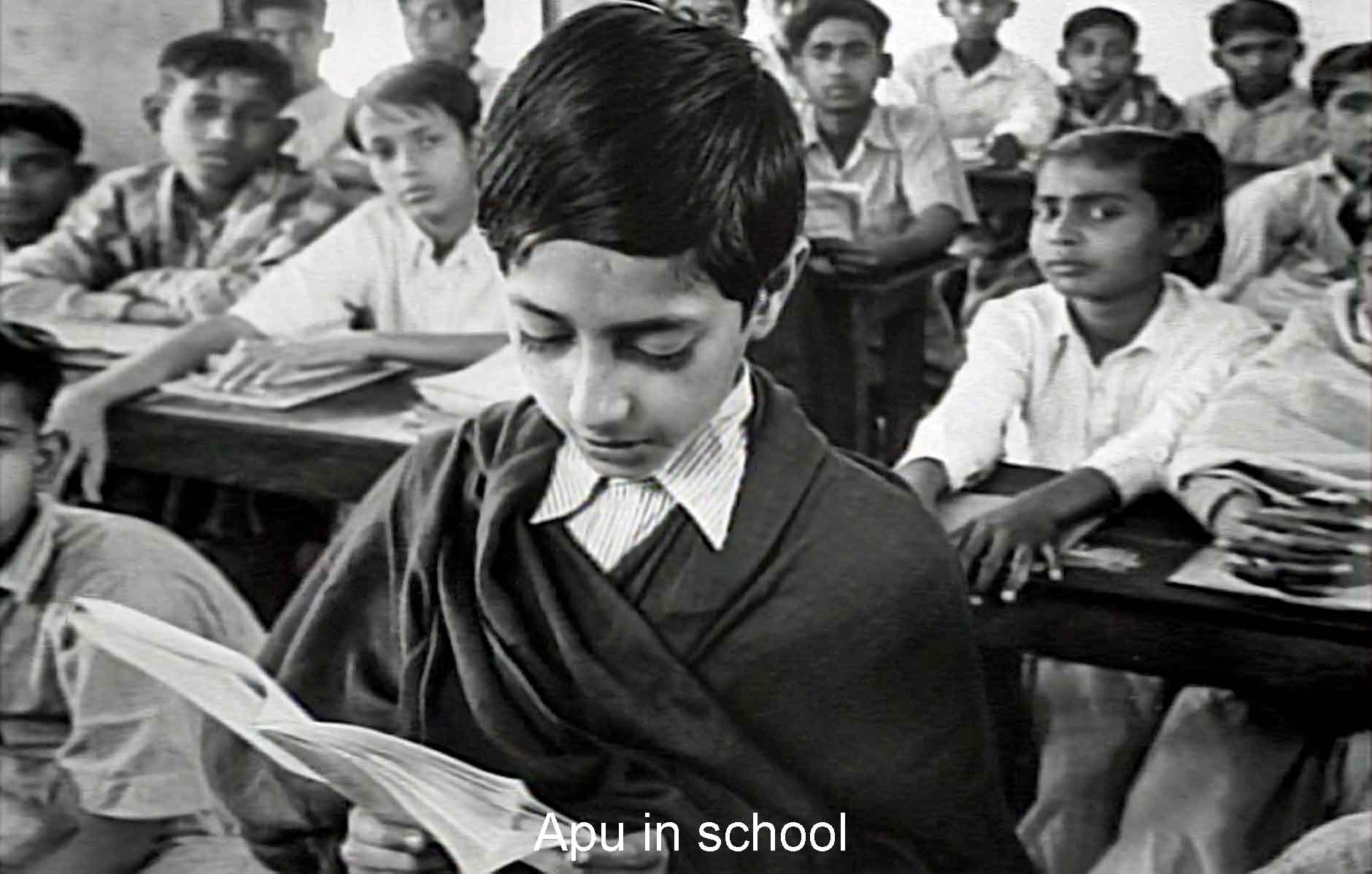

The father contracts a mysterious illness and, made sicker by the fireworks fumes from a religious festival, he dies. Sarbajaya has to work as a maid. Then with the assistance of her great-uncle, the boy and his mother go to live on his property in an outlying village. There the boy Apu, since he is a Brahmin, is pressured to become an apprentice priest. But he discovers a school nearby and persuades his mother to let him attend. He quickly becomes the star student, and after some years he gets a scholarship to the university in Calcutta.

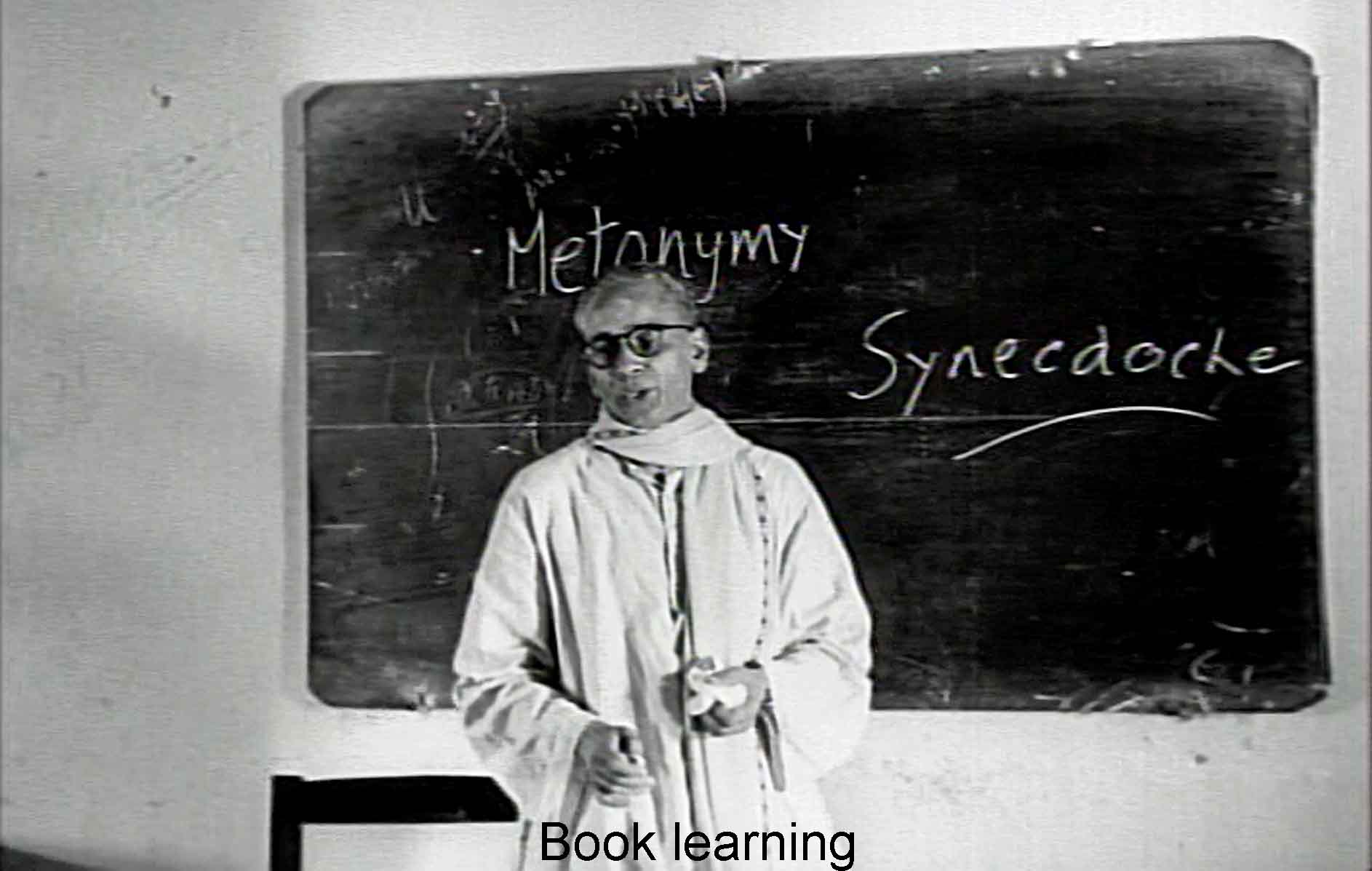

The city contrasts with the village. It offers book learning—history, geography, poetry, astronomy, physics, chemistry—all these forms of abstract knowledge that contrast with the village’s more human values, bodies, religion, and family, especially mother.

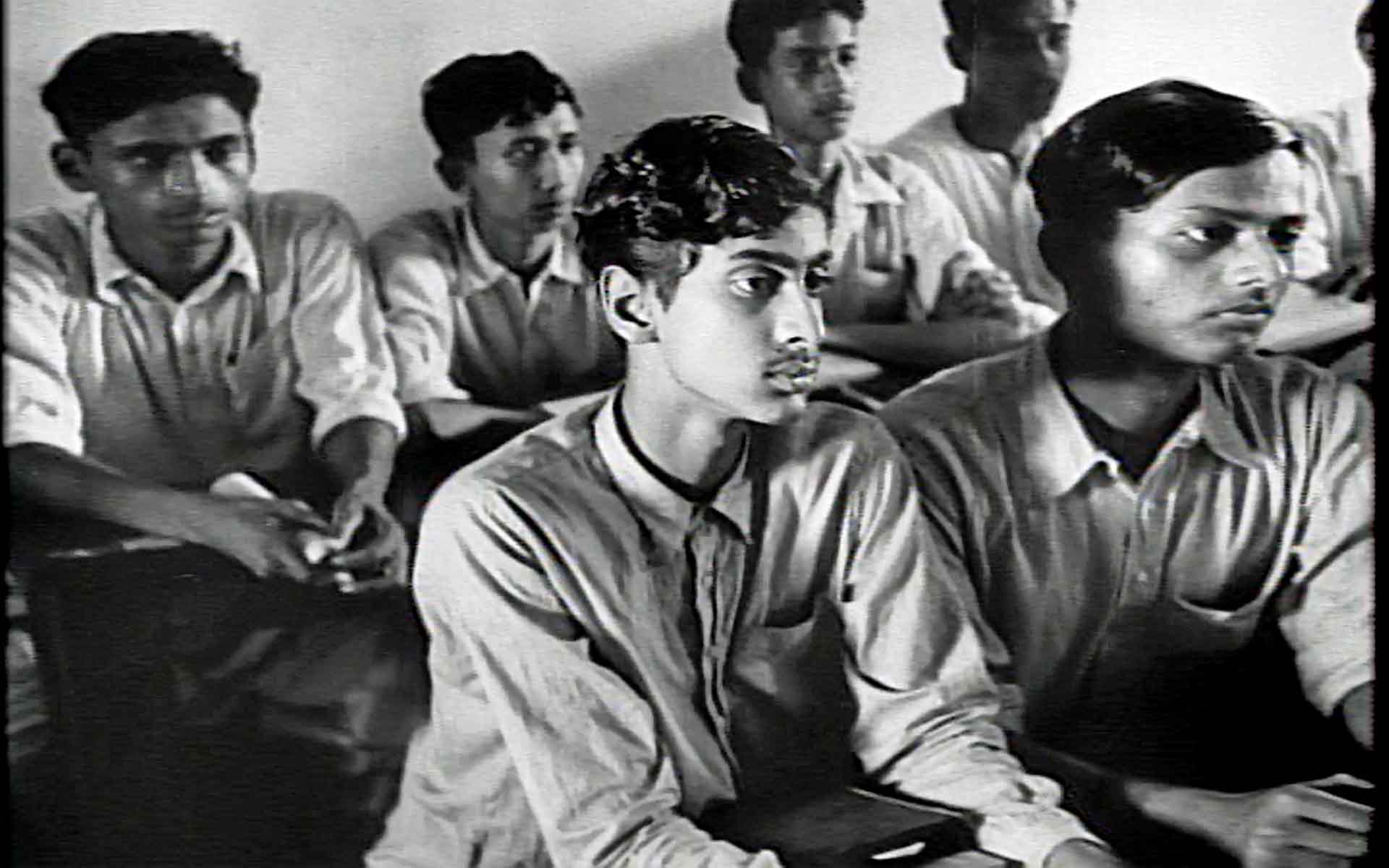

Apu becomes a teenager, complete with a tentative mustache and played by a different actor, Smaran Ghosal. Apu becomes totally committed to his university studies punctuated by occasional wanderings with a rich friend and a job nights at a print shop. So committed is he that he neglects his mother more and more. Back in the village, she pines for him and begins to fail in health. Ultimately she dies, waiting for him, watching the Calcutta trains pass. He feels the loss deeply, but nevertheless determinedly returns to his studies.

Ray does not close with the boy’s learning of his mother’s death. He ends with Apu beginning the return trip to Calcutta to learn, to progress, to move on. Motion is a major theme in Aparajito, from the opening shots out the window of a moving train to Harihar’s painful climbs up the riverside stairs, to Apu’s running around Benares to his final walking to a train, and the train is a recurring symbol of progress in all three films of the trilogy. Yet the foodseller on the train, right within the symbol of progress, reminds us of the more body-oriented cluster of traditional values. Apu ignores him as he ignores them.

The food seller is one of a number of explicit symbols in the film. In Pather Panchali, the novice filmmaker let the ordinary actions in making a film spell out the relationships of the characters and the action. The movement of the camera, the use of close-up or long shot, the length of a take, framing the subjects, from all these we could infer what was going on in and between the characters. Ray built this kind of moviemaking from the watercolor storyboards he made for his own use only. A wonderful example in this film is Apu’s return from college when he falls asleep instead of answering his mother’s eager questions—shades of my own college days and a beautiful example of Ray’s neo-realist style. But also, in this film, Ray includes some explicit symbols, obviously put in the movie, separate from the overall action, in the manner of filmmakers dating back to Eisenstein. Ujjal Chakraborty points to a number of these symbols in a commentary on the Criterion Blu-Ray of the film.

The father dies, and Ray cuts to a flock of pigeons flying off. Perhaps it is the same flock of pigeons being fed as part of the morning religious rituals by the Ganges. In Bengali there is a phrase pran pakhi, meaning life represented as a bird—hence the symbolic meaning of the flock of pigeons. Ray gives us a similarly explicit symbol at the mother’s death: fireflies in the forest flickering, lighting up and going out as happens with us humans. Apu, learning of his mother’s death sinks down by the roots of a tree—she was his “roots."

There is a cloud over Apu’s head as he walks toward the train in the last shot. That could be one of Ray’s explicit symbols, or it could be something in his earlier style, just there but telling.

The white handkerchief Apu’s university friend carries tells us he is rich and doesn’t have to worry about doing well in his classes as Apu does. This rich kid’s taking up smoking marks his easy transition into modernity as opposed to tradition’s pull on Apu.

The shots of Apu working at the printing press, I think, say something about the kind of learning we get from paper: repetitive, laborious, but new and fast, very different from what he handles in the village, figurines representing gods.

Outside the window of the sick father’s room we see fumes from the fireworks of the Kali puja festival of lights, fumes that will kill him as they do some Indians every year.

Chakraborty notes that the river and water in general are another important symbol. It is constant yet it flows on and on, as human life does. He suggests that Benares itself has a symbolic meaning. It is a place where people from many different regions of India, speaking many different languages, come. And it signals Apu’s becoming more cosmopolitan, as we will see him in the third film of the trilogy.

Progress is Ray’s theme in all the three films, progress in which one gains something but inevitably also loses something. All three films have deaths in them, deaths that Apu must accept and integrate into his growing self. We see Apu’s progress, but also the progress of India in things like the train, an automobile in Calcutta, electric lights, and so on. This idea may explain the English title of this film, The Unvanquished.

Motion dominates this film, and with it the idea of both gaining and losing. The duality is inherent in the very idea of motion: When you move you gain a new position and lose an old one. In this film Ray uses motion to symbolize progress: the motion of the train in the opening shots; the motion of the boy running through the narrow streets of Benares; the father’s climbing up and down the stairs in Benares; Apu taking the train to the university in Calcutta, and so on. By contrast the mother is static, a constant. A key word critics use for the mother is “enthralled," and it is nicely chosen. It suggests both sides of her relationship to her son. She is fascinated and in love with him; she is also a slave to him. And the acting of Karuna Bannerjee beautifully makes this duality visual, especially in the moments of her dying.

In general Ray uses two distinct styles of moviemaking in this film, and the two styles contrast two kinds of living. One consists of the city, the printing press, book learning: history, literature, mathematics, above all, science. This is Apu’s learning and growing, and Ray presents it more in the style of a conventional filmmaker with rapid cuts from blackboards full of symbols to a chemistry experiment or a magnet. His other style is the naive neo-realism of Pather Panchali, and with it he represents a traditional and more personal cluster of values: body, family, tradition, religion.

That is Ray’s core theme in all three films in the Apu trilogy, progress—in this film progress in abstract knowledge. That progress involves gain but also loss. The trilogy is a coming-of-age story, but not just for Apu, for Satyajit Ray’s maturing as a filmmaker. And far from lessening the merit of this film, his using two different styles to develop the two different modes seems to me the mark of genius, not in any way lessening the merit of this film but enhancing it.