This is a “puzzling movie,” a genre I so named back in 1963, movies like The Seventh Seal, Last Year at Marienbad, L’Avventura, The Silence, Last Tango In Paris, La Dolce Vita, and many another. They have simple plots, but sprinkled throughout are all kinds of highly symbolic images: a chess game, trees without shadows, random shots of a mountain, and so on.

The Wind Will Carry Us has this pattern. Behzad (Behzad Dourani, the one professional actor in this film) is called an “engineer.” But he is a filmmaker who has come with a three-man crew to a remote Kurdish village (Siah Darea) to film a strange scarification ritual performed by the women of this village after the death of one of their number. Guided by a boy Farzad (Farzad Sohrabi), he waits in the village for an old, old woman to die, but she doesn’t. He fields demands to his mobile phone from his producer, a Mrs. Godarzi, but she finally cancels the assignment. The film crew and he leave.

Nothing happens, but everything happens. Birth and copulation and death, in T.S. Eliot’s phrase. Behzad’s hostess gives birth while he waits for an old woman to die. From a feisty woman serving in the café she owns, he and we get a lecture on women’s sexuality, their third, “night job,” copulation. And finally the old woman, Mrs. Malek, does die.

Much in the manner of those 60s “puzzling movies,” Wind gives us symbols galore crying out to be decoded. The bone at the end. The cow kept underground. An apple that rolls and falls, and later a rolling soccer ball. A tortoise Behzad turns over on its back (but, to my relief, the beast manages to turns itself back over). A dung beetle, i.e., the scarab, a sacred insect representing the sun that sets and is reborn every day. Behzad’s face in a close-up as he shaves, the closest up close-up of the film, the camera acting as a mirror. The seeking of milk. The film opens with one of Kiarostami’s characteristic moments: men in a car trying to find their way, marked by a particular tree:

Near the tree is a wooded lane

Greener than the dreams of God.

This is the first of five quotations of poetry in the film.

Kiarostami’s elliptical way of conveying information complicates this symbolic feeling still further. “I want to create the type of cinema that shows by not showing,” he has said. Many things crucial to the film, we don’t see: the dying woman; Behzad’s television crew (although we hear their voices); Youssef, a man digging underground in the “telecommunications” ditch; his girlfriend, Zeyrab’s face; Farzad’s and Mrs. Malek’s relatives who have come for a final visit. According to Kiarostami, there are eleven important characters in the film whom we never see.

In his many interviews, Kiarostami has spoken of his wish to create a “half-made film,” one that viewers must complete through their own individual and differing interpretations. That is the answer to the “boredom” some viewers and reviewers find in his films. You have to be thinking as you watch. What is this image doing there? What might it mean? How does it relate to other images? How does it fit into the film as a whole? You won’t get anywhere using viewing a Kiarostami film passively the way we watch the usual Hollywood story-film.

We viewers are to provide meanings or, better, resonances for the film’s images and symbols through our own imaginative powers and inclinations, and it doesn’t matter if we come to different interpretations. In fact, Kiarostami prefers that we do. What follows, then, is my own reading of the film, in no sense “the” meaning.

I ask, as I always do, why is this element of the film there? Why milk? Why the apple? Why the bone? How can I understand these things as part of an aesthetic whole—as I would ask of the elements in a sculpture or a symphony. Why, for example, does Kiarostami give us an unseen man digging underground below a cemetery in a “telecommunications ditch”?

Paradoxically, communication forms a major theme in this “half-made film” that defies a single meaning. Five times characters quote poetry, mankind’s supreme form of communication. Characteristically, Kiarostami’s people have desires that drive them. Here it is the desire to communicate. Behzad wants to observe this primitive, rural ritual of scarifying women, film it, and so tell it to television audiences in Tehran and other city people. Driving this film, then, is his desire to tell something secret, the desire of an urban elite, really, to exploit these simple, underdeveloped people. And he fails. He becomes the observed, not the observer.

Kiarostami’s joke in the film is Behzad’s five trips to the mountaintop cemetery to try to get cell phone messages from his producer, “Mrs. Godarzi” (God? God-arse? Godard?). But the technologically advanced cell phone, like the tv equipment we never see, does not communicate. Instead, it interferes with Behzad’s real communications with people in the village. Ultimately it ends his quest to film the ritual. The real communication is his standing in a cemetery and his being given a bone: you will die.

The village, however, is quite different. Early on, Farzad tells Behzad, “This place is a world of communication.” The secular teacher tells Behzad as much as he ever gets to find out about this strange ritual. The boy Farzad constantly leaks things he’s not supposed to tell. But he has trouble dealing with exam questions, sharing his perplexity with Behzad (who teases him with wrong answers—talk about communication!). We get double entendres about women’s sexuality from the woman who owns the cafe. At the end, the women of the village apparently know that the old woman has died, although Behzad never found out. The village communicates just fine. But this tv director is terrible at it (more whimsy from Kiarostami).

Another theme pervades the film: verticality. Farzad, the boy guide (perhaps from Jungian symbology) makes Behzad clamber up and up to this vertical village. And later Behzad will scramble to yet “higher ground” for his useless cell phone calls. Godfrey Cheshire, in his excellent essay, “How to Read Kiarostami,” suggests that Behzad’s vertical climbs echo

the Miraj, the Prophet Mohammad’s bodily ascent into heaven. But instead of these signs, Bezhad repeatedly heeds only that faulty messenger of the flatland, his cell phone. His recurrent trips to the hilltop are like a stuttering, incomplete mock-Miraj that must repeat over and over because Bezhad hasn’t understood ’which way is up’ or where the real voice of authority is to be found. In effect, he is the tortoise that’s upside down, flipped over by his own incognizance.

Conversely, the film repeatedly invokes the underground. The first words in the film are, “Where is the tunnel, then?” In effect, we must go underground, die a little, to come to a fuller understanding of life.

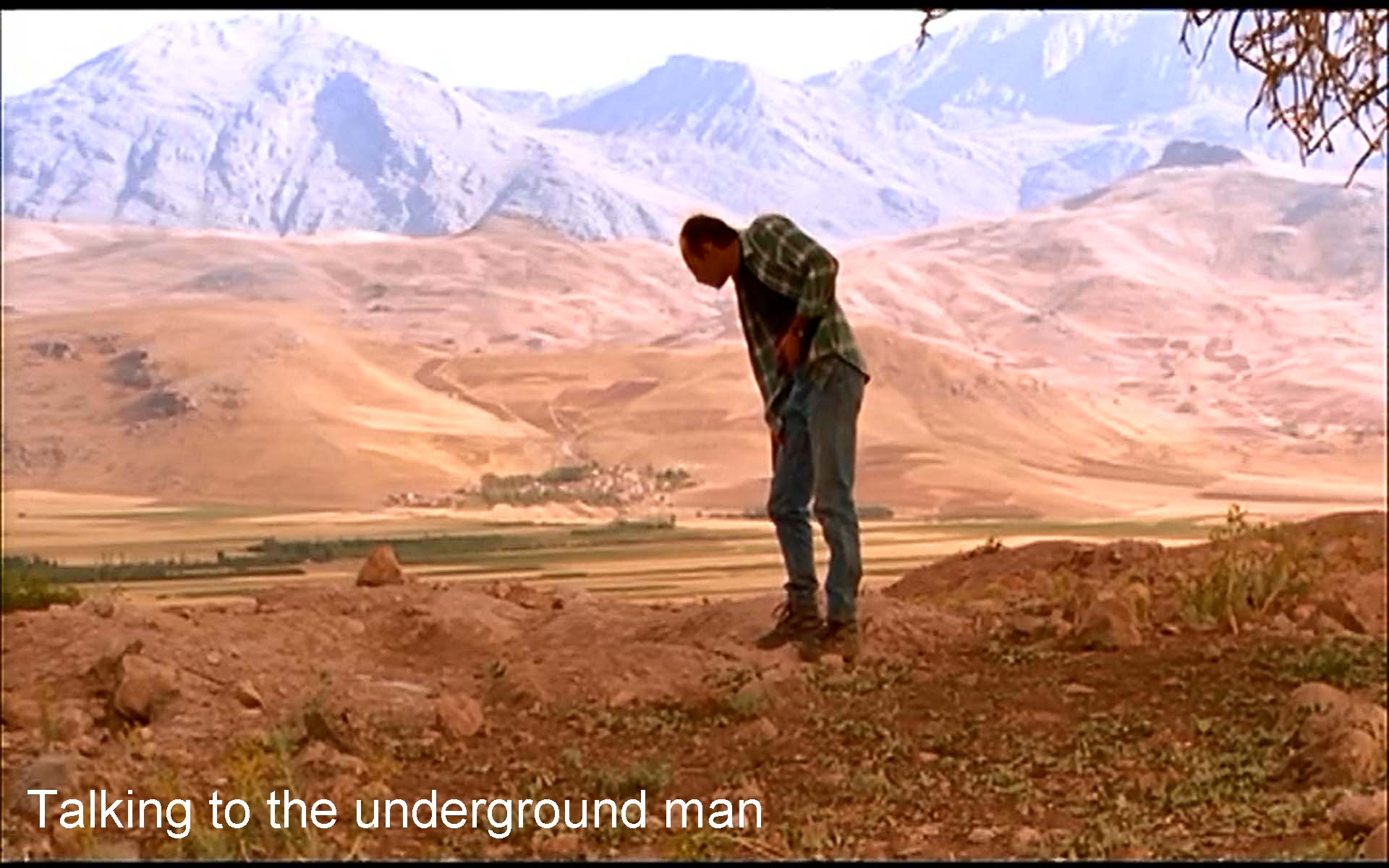

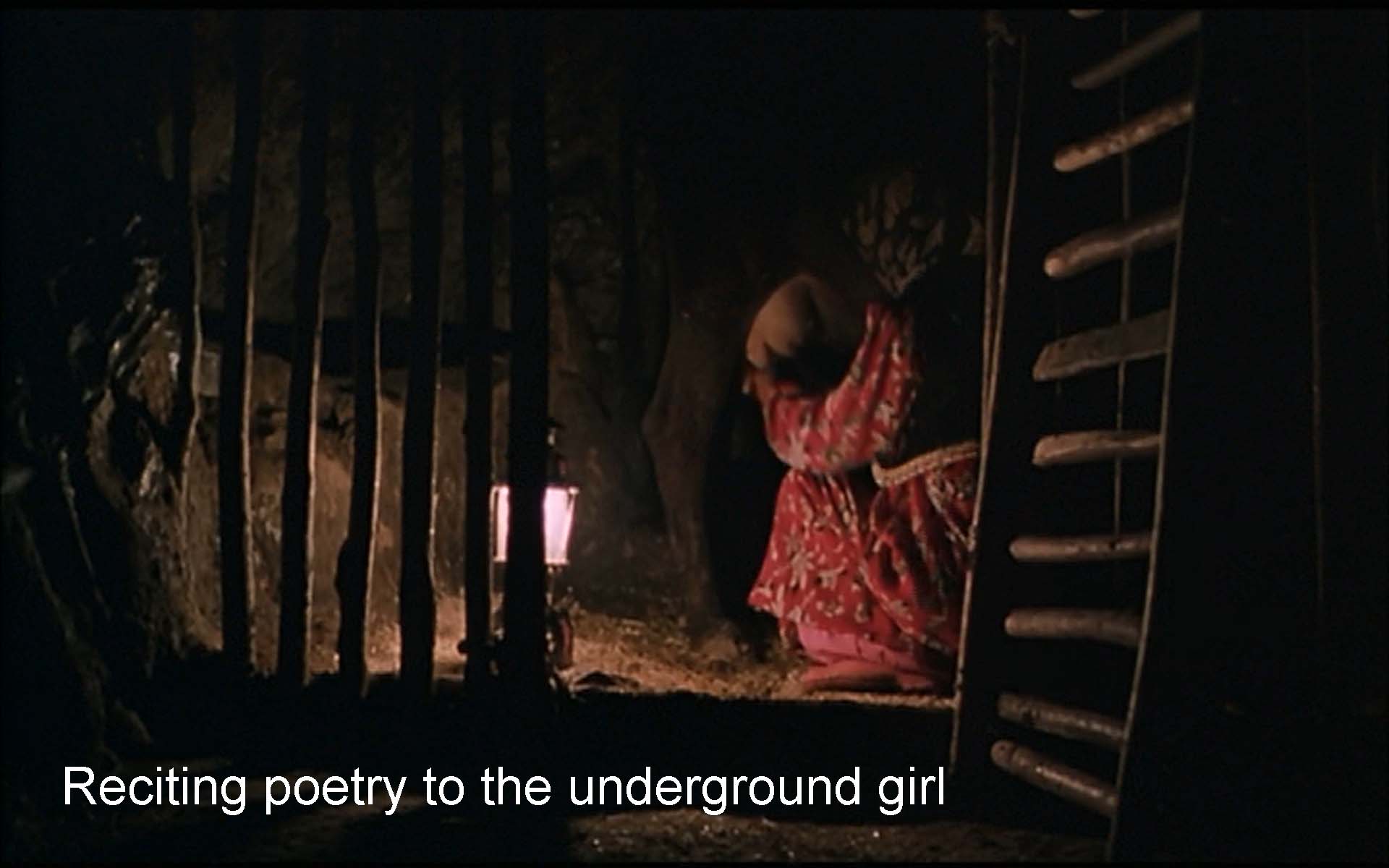

Behzad tries to disguise his plan to the villagers as a search for buried treasure (which, in a way, it becomes). You could say that the dominant image of this film is, in fact, earth, that brown, bare dirt that figures so large in other Kiarostami films. This is a film about man—and woman—on and in earth. Behzad converses with Youssef, the unseen man digging in a “telecommunications ditch” under the cemetery on the hilltop. Several times Behzad has sought milk. Now he asks Youssef for some.

Milk has many possibilities: sustenance (like the tea plentifully dispensed); dependency; the link between mother and baby; sperm; purity; the “milk of human kindness”; the biblical milk and honey, and so on. Now Youssef tells Behzad to go to his girlfriend Zeyrab for it. To get the milk, Behzad has to go to an underground byre. There a young girl, whose face she will not let us see, milks the cow. Godfrey Cheshire mentions a famous tradition (hadith) of the Prophet in which Mohammad, asked the meaning of milk in a dream he’s had, replies, “knowledge.” Behzad, ineptly flirting, recites poetry to her, the poem which gives the film its title. “In Kiarostami ’s usage,” writes Cheshire, “there’s no contradiction between ‘sex’ and ‘knowledge’; rather, comprehended by poetry, the sensual and the sacred connotations reflect, reinforce, and explicate each other.”

Forugh Farrokzhad, the most famous female author in the literature of Iran, a strong feminist, wrote the poem Behzad recites. Here are its last lines:

Place your hands like a burning memory

In my loving hands

Give your lips to the caresses

Of my loving lips

Like the warm perception of being

The wind will carry us

The wind will carry us.

In effect, we need to give ourselves up to experience, especially sexual experience and procreation; we must cease to strive and let the wind take us through birth and copulation and death. Alberto Elena in The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami quotes him: “The Wind Will Carry Us means that sooner or later we have to die, and for that very reason we should enjoy life before the wind tears us, like leaves, off the tree where we thought we would stay forever.”

But I think Wind is as much about life as about death. The tortoise that rights itself, the scarab tirelessly carrying its ball of dung, the woman who has given birth, the crops, the discussions of sex with Behzad’s hostess and the café owner—all these speak to me of a life force against which the human drive to communicate plays out. The film, I think, is as much about death-and-rebirth as death alone: the car that "gives up the ghost" at the beginning but recovers; the crops that must die and be replanted; the tortoise that recovers, and above all Youssef's ordeal.

Youssef, the underground man, gives Behzad a bone he has dug up, a femur that Behzad measures against his own thigh: this is our destiny, to be bones in the earth. At the end of the film, in its last minute, Behzad tosses the bone into a little stream where it floats down (like the apple that rolled earlier in the film), rejoining the world of the living, flowers, goats feeding, and water flowing (like the rolling apple) to an unknown destination.

The bone, to me, signifies death-and-rebirth, like Youssef himself, who almost dies when his tunnel collapses. Behzad gets help—the one useful communication he achieves in the film—and the villagers save the man. Help includes a doctor (another Jungian “guide”?, a “guardian angel”?). Reciting lines from Omar Khayyam, he states one possible “moral” for the film: ignore ‘promises’ of the beyond and instead, “prefer the present.” But has Behzad learned from this death-and-rebirth? At the end, he snaps forbidden photographs of the women about to mourn the old lady who has, apparently, finally died. Once a filmmaker, always a filmmaker. Communication rules.

In other words, that human desire to communicate—and how much of this film is simply dialogue, no action—plays out against the natural cycles of, yes, birth and copulation and death. Wry, complex while seeming simple, visually beautiful, The Wind Will Carry Us will richly repay your (and my) thinking about it. Kiarostami’s ironies and opennesses become a postmodern aesthetic for the twenty-first century, building on your and my individual responses. In this case, they might well include awe.