In this exquisite Australian film by Nicolas Roeg, the opening shots, purely pictorial as they are, set up some basic motifs. Under the credits, we see the flowing shapes of a rock wall. As the film begins, we see the rectangles of a brick wall. The reviewers all pointed out the obvious about this film. It’s about two cultures and the barriers between them: brick walls and rock walls. And around it all the hauntingly harsh and industrial music of Stockhausen’s “Hymnen.”

But before these shots, the film gives us two other things. A voice over says: Faites vos jeux, messieurs, ‘dames, s’il vous plaît, a croupier telling roulette players to place their bets. Why? At the end of the film, we will, sadly, know.

We also get before the film starts, a title card, a note that Roeg did not want. (He wanted us to figure it out for ourselves, he tells us on the DVD.) The title card explains the “walkabout.” Among the Australian aborigines, a boy at sixteen is left out in the desert to survive on his own for a period of months, and so show that he is ready to be a man.

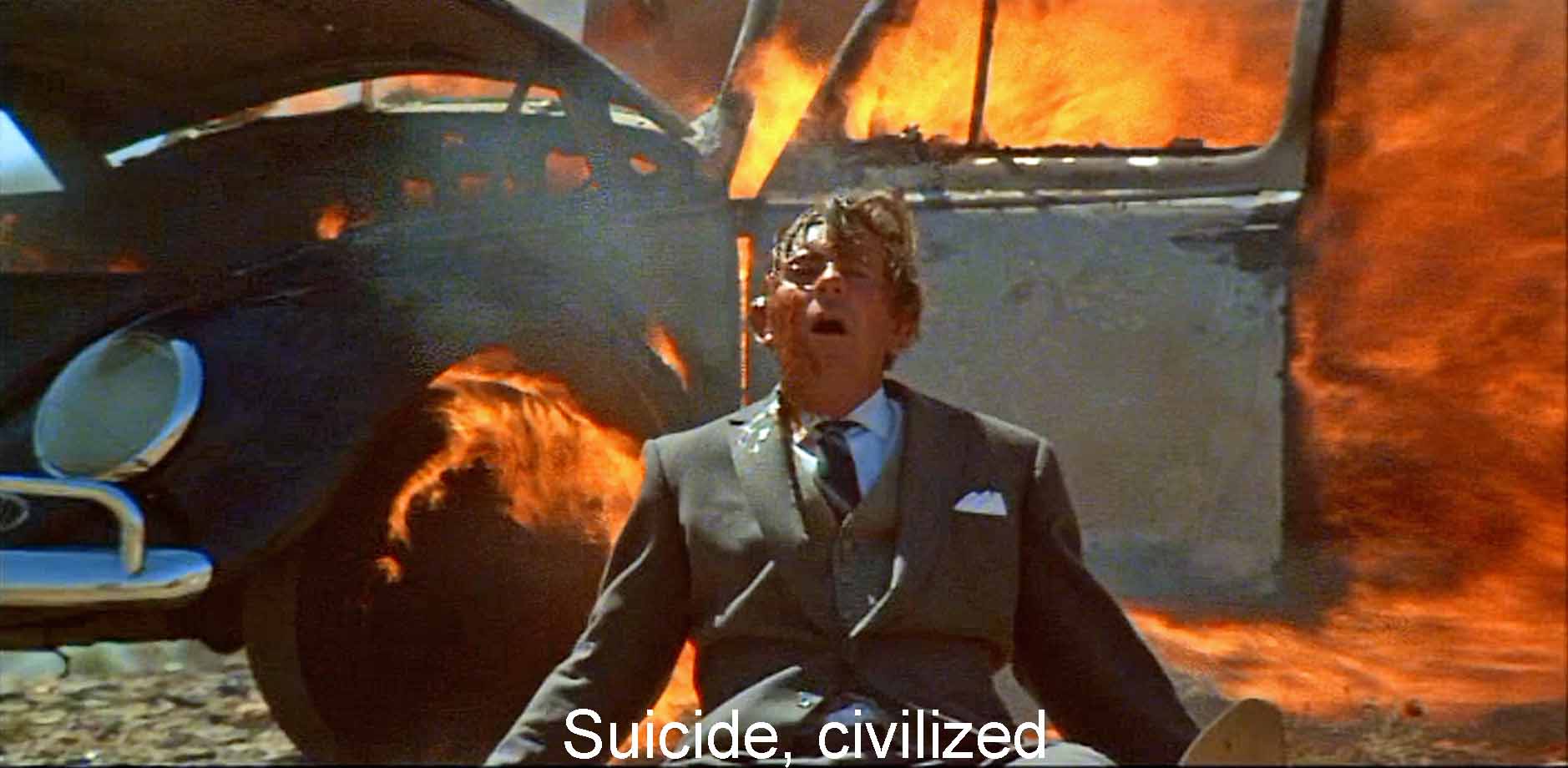

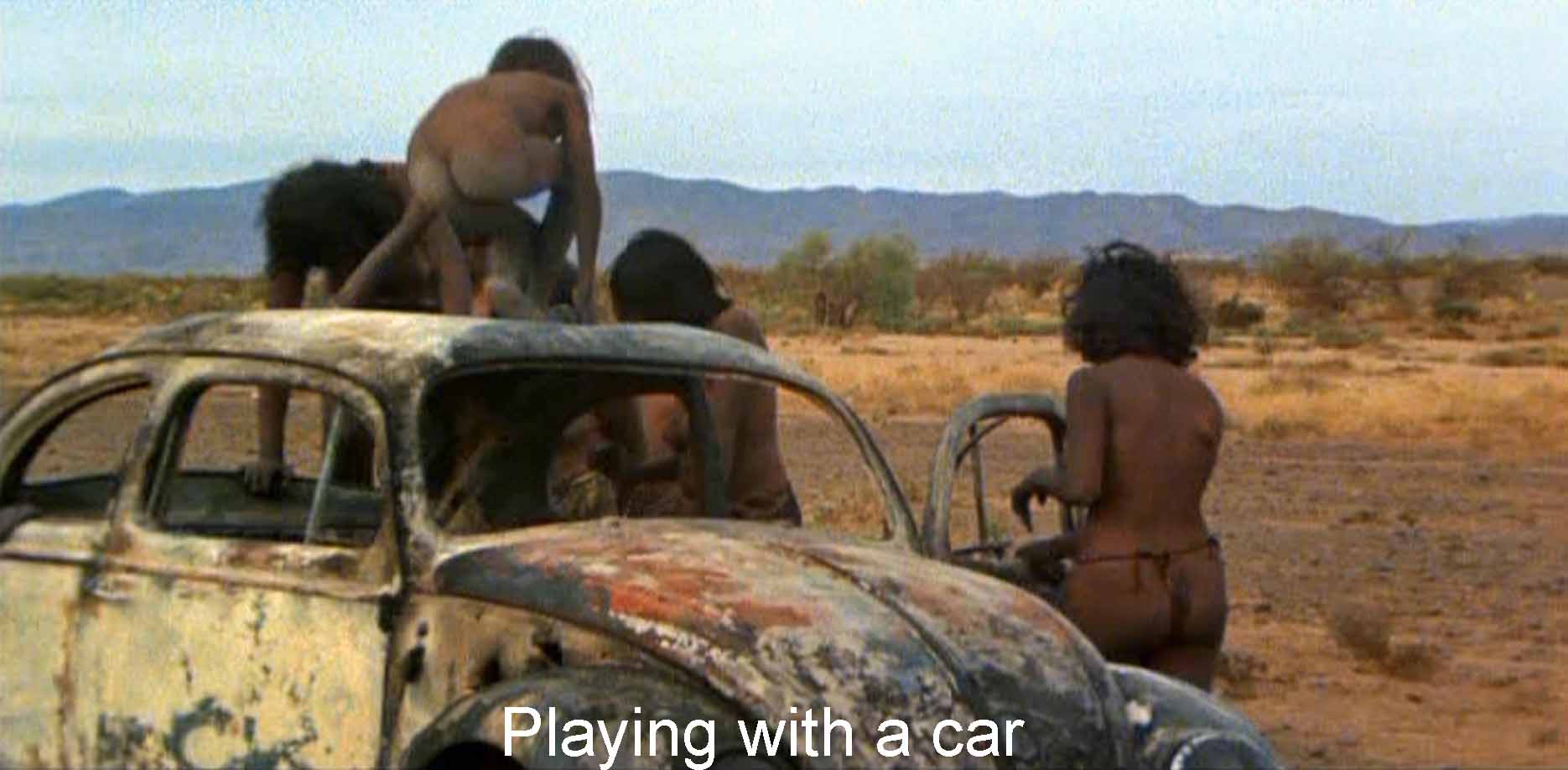

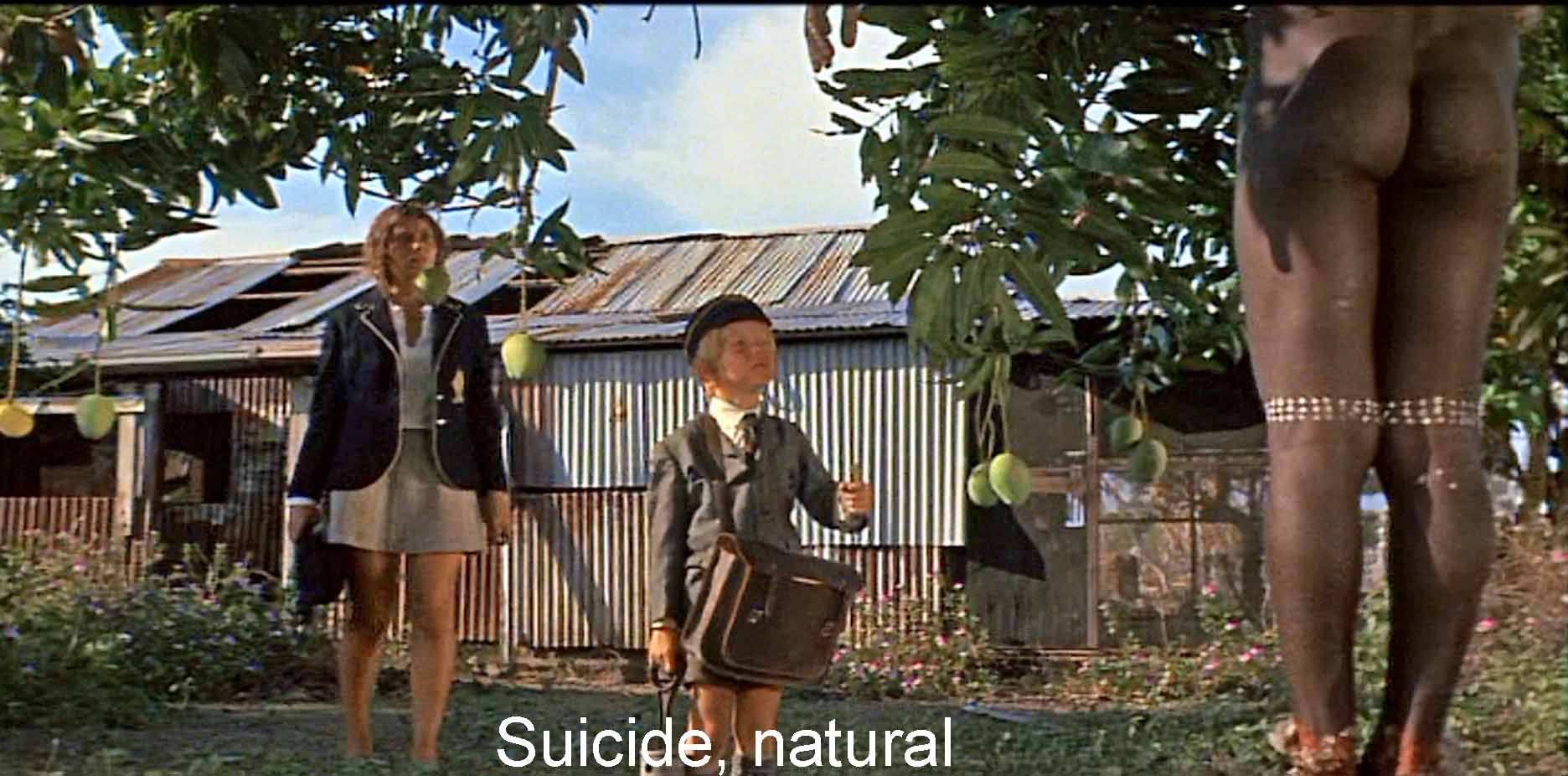

As for the two cultures, we see the Australian whites, we see the aborigines, but, most importantly for this picture, we see parallels between them. There is the father’s unexplained suicide and the young aboriginal man’s unexplained suicide, much later. The aborigines play with the car as the children play with a tree. There is sexual desire in both. Above all, there is the aboriginal’s walkabout and the girl’s and the boy’s walkabout.

The aborigine, the young man, is unnamed in the film. Since he is played by David Gumpilil, I will call him David. Similarly the never-named girl and boy I will call by their names in James Vance Marshall’s novel on which the film is based: Mary and Peter. Pretty Jenny Agutter, fourteen at the time the movie was made, plays Mary, and Peter is Jean-Luc Roeg—yes, Roeg’s son, six at the time.

Parallels between the two cultures includes the white children’s efforts at survival as opposed to the aborigine’s far more successful efforts. Roeg highlights the contrast by cut-in shots of the neat prepackaged food of the whites in a butcher shop and the lizards and small mammals David kills for meat. (Once, when I was showing this film to a class, at the close-up of a half-dozen dead fly-covered lizards hanging round David’s waist, two women auditors fled and never returned.)

There is a two-culture parallel between the father’s papers, which include geological drawings, and the art pointed to by the aborigine, petroglyphs. The “factory” in the desert making kitschy lawn ornaments and tourist stuff points to the ruinous effect on art when the two cultures combine. And, indeed, from the “civilized” art I get a feeling that art is futile when compared to the wonder and beauty of the natural scenes in this film.

So far as survival is concerned, we see the white hunters slaughtering buffalo contrasted to David’s killing only what he needs for food for himself and the people he is rescuing. We see the waste and litter of the abandoned mining company, and part of that litter is the half-crazy white watchman left behind who values the company’s rusting property over the lost children. (Throughout, one of the signs of civilization is rubble and abandoned objects.)

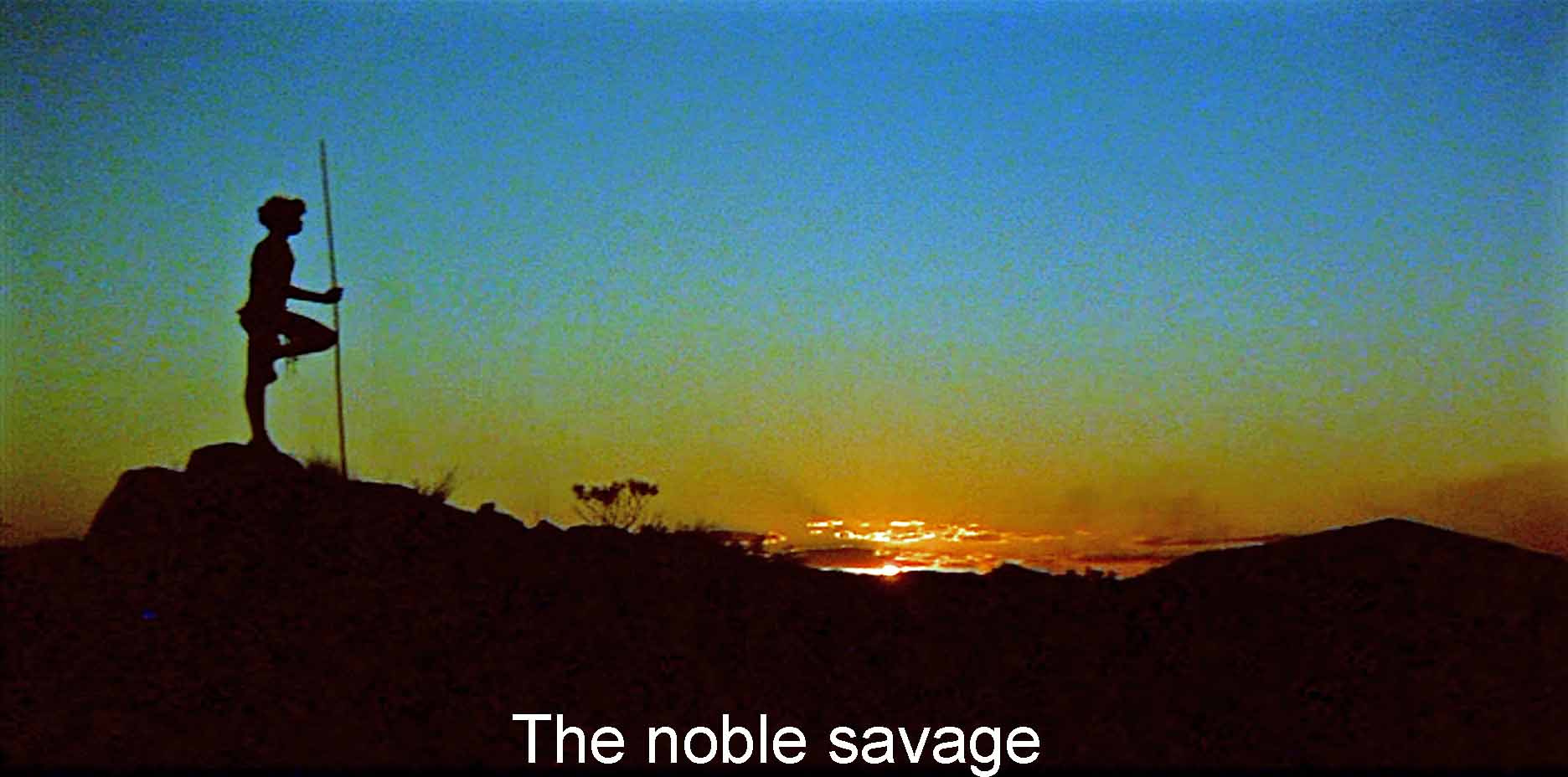

At first glance, the film looks like a simple contrast of the noble savage with the frets and discontents of modern civilization. To be sure, there are a lot of beautiful pictures of the desert the aborigines inhabit at the expense of the crowded and confusing world of the whites in Adelaide. People come in anonymous crowds—there is no way you would recognize the principals of the film unless you had seen it before. By contrast, the aborigine, when he first appears or later stands watch, is solitary and nobly erect. When an aborigine family discovers the father’s burnt-out Volkswagen, each individual stands out. In nature, the camera gives us constant shots of individual small animals. Only the insects eating dead animals come in hordes like the city dwellers.

Roeg in his comment for the DVD calls the aborigines “unfeigned” and contrasts “the manners of life” with “the manners of society.” In this vein, you could compare the coming of age implied by David’s walkabout with the enunciation class for the white girls or the silly radio prattling on about fish knives. Nevertheless, whatever Roeg says, and no matter how bad the whites look in this film, I think it would be a mistake to read Walkabout simply as a movie about the “noble savage” and the corruptions of civilization. For one thing, Roeg resolutely parallels them. And then there is that curious frame of casino gambling around the film, however; it complicates the picture.

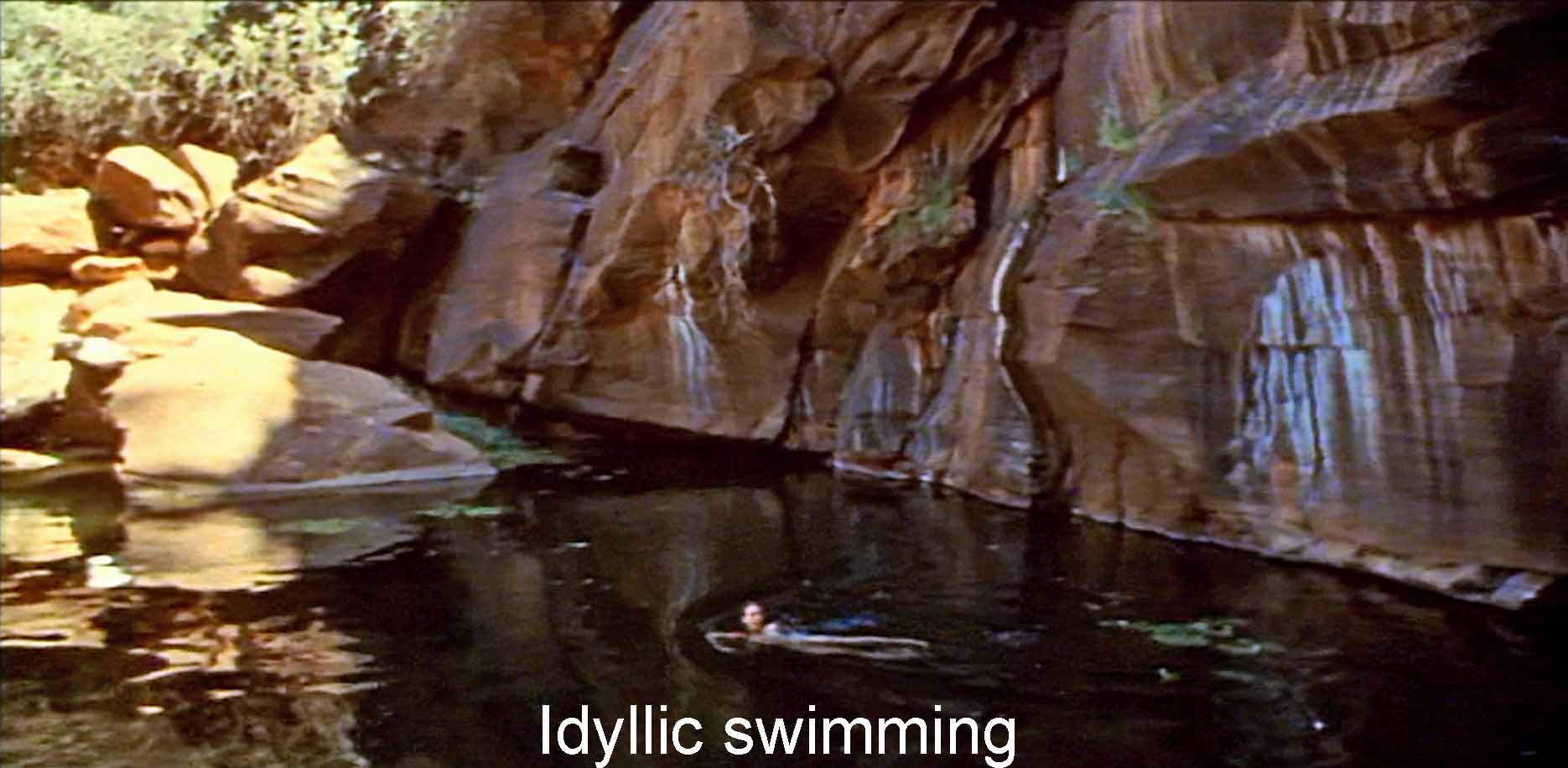

There is another cliché one could use, if so inclined, to read this movie. It’s about “failures of communication,” and you could say they are symbolized by the walls under the opening credits. In the city, the deserted town, or the abandoned farm, Roeg shoots again and again at walls, doors, fences, windows, screens, railings—barriers of all kinds. (The repeated bricks are like the anonymous crowds.) The family’s swimming pool is walled-in, unlike the ocean in the background or the idyllic desert pool where Mary swims. The first sign of the children’s return to civilization (at the farm) is a fence, and when they get to the deserted factory town, a watchman screams at them, “Private property!” The aborigine can suck water from the earth, but the whites’ civilization has hard surfaces. When the girl finally comes to a “real road,” she steps deliberately, crunchingly on it. In the scene of the scientific team, one scientist keeps staring at a piece of rock while all the others stare at the woman scientist’s breast. Then the aberrant scientist stands up and sucks her fingers.

Attempts to cross from one culture to another fail. The characters keep to their culturally approved clothing. The white children continue to wear hats and coats and even a necktie, while the aborigine wears only a loincloth. The boy takes off his shirt, but he gets sunburned. It “wouldn’t fit” the aborigine. The camera takes constant shots at and up Mary’s miniskirt. Finally Roeg, as it were, puts hesitation aside and shows her swimming nude—nothing between her and the water. Contrast the “peeping” of the Italian meteorological team: oblique, indirect, with underwear between the woman’s body and the hungry eyes. When the aborigine takes off his loincloth and does his naked courtship dance, if that is what it is, the girl does not or does not want to understand. Clothing is a barrier, but culture is what makes clothing a barrier.

In the opening shots, crowds of whites walk silently. Nobody speaks. The father does not talk except to rebuke his children, and we never know why he is committing suicide or trying to shoot Peter and Mary. Enigmatically, the radio plays, “Who saw him die? / I, said the fly,” and there are surely flies aplenty in this film., The lecherous Italians in the meteorological team do not understand the Australian scientist, nor he them. Just before David gives up his mysterious dance and goes off to suicide, the ultimate failure to communicate, Mary announces that the radio’s “gone.” In the outback, we sense that there are people just offscreen (the meteorological team, the woman at the statuary factory). They could help the children, but they don’t. And even when the children have found “civilization,” the abandoned mine, they are rejected. We never know how they get back to the city from which they came.

Throughout, communication fails because of language. Mary and Peter cannot understand David, nor he them (although the as yet uncivilized boy learns a few words of David’s language). At the end, David has learned one word: “water” which he offers to the girl to win her favors, but she ignores the gesture. Peter chatters away—it doesn’t seem to matter that David doesn’t understand and his sister could not care less about what he says. In the beginning, we don’t hear the people in the city talk at all. Mary plays her radio instead. At the end, I can barely understand the young husband’s gibbering about his job.

But perhaps the most telling failure of communication is Roeg’s own. He both directed and photographed, adopting a deliberately uncommunicative film style. He gives us incomprehensible cuts to small animals, lizards, insects, an echidna. He uses “ghost cuts,” for Peter’s imagining of the early explorers or David’s stopping time as the hunters kill. (Is this really happening? Or is the aborigine remembering or imagining it?) Roeg gives us a language we cannot understand in a sound track difficult to hear, scarcely audible voices from the radio, episodes like those at the statuary factory or the rusting mine or the meteorological site that one cannot understand. Ultimately, Roeg puts communication between director and audience at stake. The whole film could be Mary’s memory. Or her fantasy.

Roeg’s camera—he did his own cinematography— also shows a lot of “action at a distance,” with reaching across the barriers. He makes much use of telephoto lenses. Such a lens makes the near and far seem at similar distances from the camera. It compresses and undoes depth. It crosses spatial barriers. It tries to undo the barriers. Conversely, for the desert scenes, Roeg uses a great many wide-angle shots. As Roeg set them up, these wide-angle shots bring the near nearer and put the far farther away. They stretch depth, creating distance and spatial barrier. Particularly “stretching” are pans with the wide angle lens: the edges of the frame seem to come forward and go back again as the rotating camera brings them into the center of the frame and out. Mountains loom up and recede back. All this, for me, reinforces the idea of barriers between people (between Roeg and me) which may be crossed or may not.

One can read the film more subtly, though, than by these two clichés: natural vs. civilized humans; barriers to human communication. Think how much of this film is concerned with movement. We begin by seeing people walking about a city, a father coming home after work, a girl walking home after school, her brother doing the same. The father drives the children into the desert, the outback, stopping when he runs out of gas. The little boy reports that the wheels come off his car. Then the father burns his Volkswagen, so that it will not run any more, eventually becoming a toy for an aborigine family. From then on, in the parallel walkabouts, David, Mary, and Peter are moving, moving, moving. In a series of apparently trivial episodes, when the boy plays with his toys, he moves them. David moves when he hunts. The whites are constantly trying to get somewhere, toward civilization or some city—home. The Housman poem recited at the end of the film speaks of “The happy highways where I went / And cannot come again.” The title and the action are walkabouts.

I suppose it’s obvious that a motion picture would have motion in it, but I think something more complicated is going on. I find that I can understand the film by means of a hidden family of metaphors (as described in current metaphor theory by George Lakoff, Mark Johnson, and others). It is one of our most common ideas, that LIFE IS A JOURNEY. We use it all the time in expressions about our lives like, “I’m off to a good start,” “I’ve come to a crossroads,” “I’m carrying too much baggage,” but most relevant to this picture, “I’m lost.” This is a film about lost people, notably the father, Mary (both during the walkabout and in her adult life), and all the city dwellers. Paradoxically, those who seem most anchored in place, the city dwellers, the factory people, or even the meteorological team seem most lost. The children and David are finding themselves—until the fatal failure of communication between David and Mary.

Life is movement, literal movement, like the aboriginal walkabout, not metaphorical, like the boy’s toys. And here, as I read it, Roeg’s film touches on something Roeg could not have known in 1970: recent neuroscientific thinking about a basic brain system for SEEKING. As developed by Jaak Panksepp, this is a dopamine-driven system running from the deepest, earliest parts of our brain to the most advanced, something we share with at least all mammals and perhaps all animal life. This SEEKING system keeps us foraging, hunting, sniffing, hoping, constantly looking for things that will favor our survival or reproduction. It is Freud’s libido. It is what drives us through our evolutionary destiny. We expect to find something good for our survival and reproduction in the world around us (although, of course, we don’t always find it). When we get that something and use and enjoy it, other emotions come into play: fear, anger, lust, caring, and so on, and when they have finished, we resume our constant foraging.

This film, it seems to me, takes us back to that elemental level of humanity: the human being SEEKING against barriers and obstacles. And, tragically, these humans do not find. This film takes us back to our biology, red in tooth and claw, but also very beautiful—all those shots of landscapes and animals, alive and dead and decaying.

What do human beings seek in this film? Food and drink, most obviously, and a place to sleep. (The film is bracketed at beginning and end by two women preparing food, homemaking.) Humans seek companionship: both David and Peter chatter away, although both know that the other cannot understand him. The three on walkabout SEEK obviously, the city dwellers in a more sublimated way (the meat wrapped in plastic), but all the humans are doing the same things. And the prattle on the radio, the silly talk about fish knives, the pop music, Mary’s enunciation class, her keeping their school uniforms neat and clean even in the desert, the chase after the weather balloon (useless for their real needs), the people in the city walking to work (the father cannot stop working even as he is about to commit suicide)—all these parody our basic biological destiny, to SEEK. The three on walkabout are living the heart of life as we might have lived it a million years ago. Almost.

What else do these foragers SEEK? Sex. From the moment we see Jenny Agutter in her schoolgirl’s short skirt, sex is an issue. It is also with David’s loincloth barely covering his genitals. The film gets explicit in the tree-climbing scene where Mary climbs a tree, and we and David see her panties, which are followed by seductive shots of the tree limbs like her crotch. She goes swimming nude (but alone), and Roeg’s camera lingers on her body. The film gets explicit, even funny, with the lustful looking of the meteorological team where the men are playing with a deck of nudie cards or flirting with the woman scientist. (Watch that cigarette spring erect!)

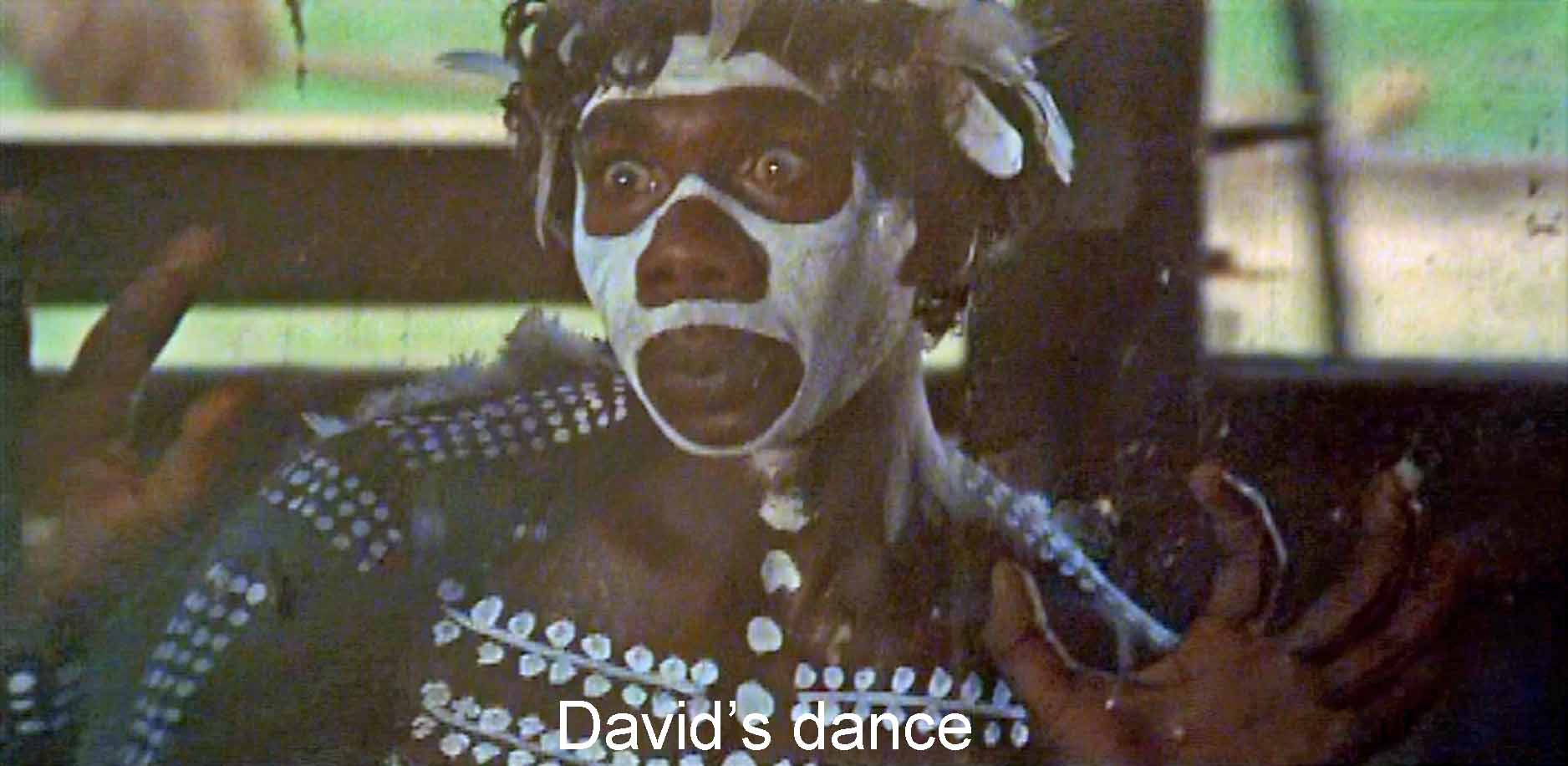

Finally there is David’s dance with loincloth removed, although it seems as much about death as about sex. As the girl domestically does laundry, the aborigine immerses himself in a field of bones, paints himself with a skull and bones, and does a naked dance before the girl, uncovering his erect penis. Having finished his walkabout, is he now free to approach her as a man? In any case, frightened by what she takes to be his sexual advances, she rejects him, keeping her little brother by her as a chaperone. All through the film, she has been clinging to the proprieties as she clings to the school uniforms. But now, as Roeg says in his commentary on the DVD, David has given her the house, which he assumed was what she wanted. But, instead of mating with him, she turns away from him. David sends Peter and Mary to the road, and he himself commits suicide, an act to which she is supremely indifferent.

Without the commentary, though, I, at least, do not understand the dance and the suicide that follows it (and perhaps that is the point). Neil Feineman, in his first-rate book about Roeg, gives four different ways to read the aboriginal dance and David’s suicide. Two make sense to me. When he waves the yellow flowers in his dance, he is inviting her to mate with him. But when Mary rejects David, he has failed the walkabout, he is not a man and must die. Alternatively, he loses his will to live because of the white hunters’ killings. He looks at the maggots crawling over the slaughtered buffalo and despairs. When she rejects him, he sets Mary and Peter free and dies himself. Perhaps the dance was an invitation like Herrick’s poem, “To the Virgins, to make much of Time,” an invitation that combines reminders of death with invitations to sex. But I think one cannot tell, and Roeg doesn't want us to. She certainly rejects him, and her indifference to his suicide remains especially enigmatic. It is one more instance of the barriers to our SEEKING that this film is about: the walls, the inability to communicate, civilized sublimations and proprieties, the failed sex, the failed love—and our own questionable efforts to make sense of it all. This is a film about our human biology: movement, food, sex, sleep, and survival.

Roeg skips the how of the children’s return, cutting to a final scene that gives his verdict on what has gone before and what is now. Mary is grown up and married and preparing food like her mother at the beginning (or like David in the outback). Her husband comes home from work (to what looks like the same apartment as in the beginning). He embraces her, and as he does he tells her something pointless about work. Roeg cuts, first to the rock walls, then to an edenic scene of Mary swimming nude with Peter and David, not like her solitary swim before. The last image of the film is of the boy’s school uniform hanging on a stick, shed so he can go swimming. Peter and Mary had a paradise, and now it is a paradise lost, as in the Housman poem that we hear in voiceover: “a land of lost content . . . where I went / And cannot come again.” It is our lost closeness to our biology.

There is one more thing in the film, a title card: Rien ne va plus. No more bets, closing out the Faites vos jeux that began the film. Evolution is a game of chance in which we seek to reproduce and survive. But once you have chosen your path through life, once you have made your bet (as Mary has), you can’t change it. We, you and I, unlike David, have chosen “civilization,” for better or, what seems more likely from this film, worse.

This is a film that asks us to contemplate our sameness with stone age people as much as our difference. Ultimately, I see this as a film about humans in the raw biological game of life, working out our evolutionary destiny and, sadly, failing. We seek, but we do not find. We have gambled and lost.