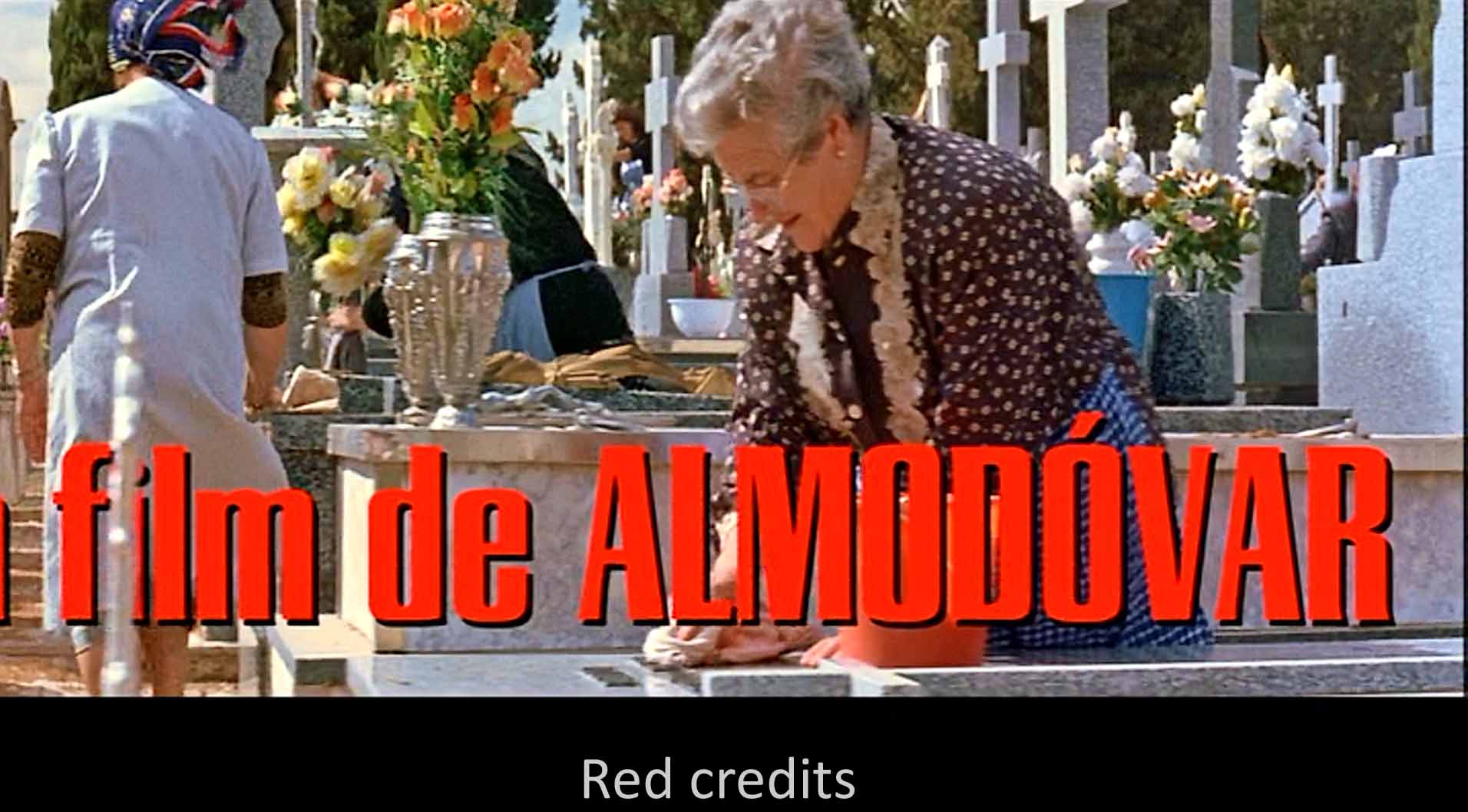

The opening shot shows us village women cleaning the graves in a cemetery—a local custom. Almodóvar closes in on three women: Raimunda (Penélope Cruz), her teenage daughter Paula (Yohana Cobo), and Raimunda’s sister Sole or Soledad (Lola Dueñas)—her name means “alone,” and she is. These three are cleaning the grave of Raimunda and Sole’s mother and father, “burned alive” in 2002. (The film’s date is 2006.) A friend, close-cropped, gray Agustina (Blanca Portillo) passes by. A spinster, she will clean her own grave. (It is a custom in this village to buy your burial plot and tend it during your lifetime.) The point of the scene is death, and in the village the dead form part of the lives of the living.

The first three go to visit Raimunda’s and Sole’s mother’s sister, ancient Aunt Paula (Chus Lampreave in glasses for cataracts that weirdly magnify her eyes). She speaks of Raimunda and Sole’s mother as though she were alive, and Sole, when she goes upstairs, sees her mother’s picture and apparently smells something on an incongruous exercise bike. This ghost-mother is Irene (her name means “peace”). The actress playing her is Carmen Maura, one of Almodóvar’s favorites, working with him again after seventeen years of estrangement. Another “return.”

Frightened, Sole tells no one, and the three women go on to Agustina’s house across the little street—in this village, neighbors count as one of the family. Agustina tells the three she has heard Aunt Paula talking to Sole and Raimunda’s mother as though she were alive. Agustina herself longs to find her own mother who simply disappeared the same night that Raimunda and Sole’s mother and father were burned alive in a fire.

Beyond this point in the plot I’d have to use spoilers, so I’ll stop here before we meet the only important man in the film, Paco (Antonio de la Torre), Raimunda’s loutish, lecherous husband. These four women (plus one to come) are what matter.

Their visiting and loud air-kissing take place in the region of La Mancha in “the village.” (It is fictitious Alcanfor de las Infantas, camphor of the princesses—and smell plays a jokey part in this film.) This is “black Spain,” rural, conservative, backward, superstitious, and church-ridden. But Almodóvar has said, “Volver destroys all the clichés about black Spain and offers a Spain that is as real as it is the opposite. A Spain that is white, spontaneous, funny, intrepid, supportive and fair.” Well, sort of.

The opposite of black Spain is urban and sophisticated Madrid. The scenes in Raimunda’s apartment and the nearby restaurant take place here, miles from the village. The village has ghosts, religion, secrets, gossip, and the cult of the dead. The city has sickness, murder—and foreign movies on the tv. But Madrid provides the safety of anonymity. Here young Paula and Raimunda can get away with murder.

The village houses the supernatural. Madrid represents the natural world. Death in the village involves ghosts and volver—return. Death in the city is more prosaic, a frozen food locker rather than a tombstone that must be tended.

As always the opening and closing shots set the themes. In the opening shot, the camera tracks in a reverse direction from the usual. It goes from right to left—a return. The credits appear in brilliant red, and red is one of Almodóvar’s recurring images. Women dominate the scene, and the women set out what will be the mysteries to be resolved, the deaths of Raimunda’s mother and father, young Paula’s grandmother and grandfather. The opening sequence gives us the themes for the whole picture: death, women, rural life, song, red, cleaning, the return, but above all women and death.

Almodóvar deserves his reputation as a woman’s director. “Volver is as manless a movie as I have seen,” wrote reviewer Anthony Lane. Two of the men who have speaking roles disappear. One is murdered, the other goes away. Two other men appear even more briefly. One makes googly eyes at Raimunda, but nothing comes of that. The other Raimunda simply shuts out.

The opening dialogue tells us that women here—in this village—live longer than men. Women are strong and noble, while husbands are sexually insatiable lechers who molest their own daughters. There are two of them, hence a pattern of “volver—return.” The women dominate. They don’t need men, who are, with the exception of the filmmaker, the artist, worthless. But women can be artists, too. At the center of this film, as in other Almodóvar films, there is a work of art: Raimunda sings the title song. (Actually, she lip-syncs to the beautiful singing of flamenco star, Estrella Morente.) The song tells of someone returning to a first love after a long time, just what this film is about: first love is mother love.

Above all, women give life. They are mothers. They nurture and take care of others. They can be sexy like bosomy Raimunda. (I like French critic Yann Tobin’s phrasing: “ses décolletés pigeonnants.”) Incidentally, Almodóvar had Penélope Cruz fitted with some extra backside to make her look more like the lead actress of Italian neo-realism, Anna Magnani, whom we see in a brief clip on a tv. (Italian neo-realism had a big influence on Spain’s post-Franco filming.)

Alternatively, women can be not sexy but drab and gray and manless like Agustina. Either way, again and again in this film women provide food and caring. And in the final scene, we see Irene nursing and nurturing the dying Agustina. Women mother, but they also live in the presence of death, as in the opening scene. Women give life—young Paula—but they also destroy life. They murder—twice in this film. Young Paula, her mother, and her grandmother all participate in murder. And the deaths strengthen the bonds between the women who, after the men are gone and the secrets revealed, are now densely related as mother, daughter, sister, niece. This double value forms the core of Volver as in Almodóvar’s splashes of red, sometimes blood, sometimes just a lively color.

Almodóvar puts lots of red in all his movies, but in this one, he lets no chance of red go by. He gives us the opening credits in red, a red sweater, the red reel of a fire hose, a bin of tomatoes, red peppers being sliced, a red station wagon, hair dyed red, and on and on. The final shot has red-skirted Irene walking down a red-tiled, red-curtained hallway. Crucially, he has Raimunda mop up a floorful of her husband’s blood, some of it with lacy paper towels. When a caller points out that she has blood on her neck, “Women’s troubles,” she explains. As Anthony Lane quips, “She could be describing the whole film.”

Think for a moment about menstrual blood. It can mean two opposite things. It signifies the process by which new life is created. At the same time, it says that that process is not making a baby at this time. It is this duality, the creation of life and the taking away of life that permeates this whole picture from the cleaning of graves in the opening shot to the revelation that Irene did in fact burn alive her husband and his lover. This village, we are told, is famous for burned houses and a wind that fans flames, and we hear about both in connection with the murders.

Wind dominates the opening scene of women cleaning graves, and the opening line is Raimunda saying, “Put some stones in the vase. Otherwise it will fall over”—the wind will blow it over and does. The wind, like red, has a double value. On the one hand, as we hear in that opening scene, it drives people crazy. On the other, it gives power and light, as in Almodóvar’s cutaway shots of the windmills on a “wind farm.” Shades of Don Quixote—this is La Mancha, after all.

The wind adds (for me, anyway) a biblical note: “The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.” (Almodóvar would know the quote as the title of a famous film by Robert Bresson.) Irene is a spirit, apparently. She has hidden from Raimunda this way, in the trunk of a car, in a guest room, as “the Russian,” under a bed, or in a darkened sedan. Having her hair dyed as “the Russian,” she reinvents her identity like many another Almodóvar character.

She is the revenant, the return of the title. But there is another return, the recurring pattern in which a husband and father molests a daughter, and the wife and mother assumes the responsibility of killing him.

First thought a ghost, Irene returns in the flesh. Mother and daughter are finally reunited tearily in the house of the dying Agustina. Death again. But the last line of the film is, “Ghosts don’t cry.” In the DVD commentary, Almodóvar says. “Actually the ghost cries, which means she isn’t a ghost but has condemned herself to live like one. She makes up for what she has done, and that’s very important,” that balancing of the books to achieve a rough justice. Irene will mother Agustina, atoning. The last shot has red-skirted Irene disappearing into Agustina’s house. There is a death in the house but also a rebirth, a return, volver.

The final credits use the patterns from various fabrics (i.e., weavings) associated with Raimunda that have appeared in the movie, the skirt she was wearing when she cleaned the grave, the skirt she was wearing when she met her daughter at the bus stop, the red-checked blouse she wears when she sings, flowers, trees, thorns—all emblems of femininity as Almodóvar conceives it.

“This is a movie about mothers,” Almodóvar says in his commentary. Mother-love is Almodóvar’s constant theme, not just in this movie. But, as the psychoanalysts tell us, babies not only love mother because she feeds them, but babies also hate her when she doesn’t. (Those furious screams of frustration.) We as adults, all of us, are ambivalent toward mothers, and mothers are toward us. Volver nicely captures that psychological truth in its double-barreled portrayal of mothers (and daughters) as both giving life and taking life. And it is so artfully done we scarcely notice that, underneath the satisfying mystery movie, lies a disturbing truth. Almodóvar shows once again how subtle and powerful an artist he is.