I was reviewing movies for WGBH-TV in Boston, when Vertigo came out. Contemporary reviewers gave it a mixed reception, voicing various complaints. They’d prefer a standard Hitchcock thriller without all the supernatural mumbo-jumbo. They didn't want him to telegraph the ending. They thought the whole thing highly improbable. I thought it was a brilliant film and said so. Now, of course, everybody says it’s a masterpiece. I was there first, though, and I feel that, in some sense I own Vertigo.

Among the more serious critics’ readings of Vertigo, I find Robin Wood’s the most telling. Wood talks about the film in terms of the mysterious, in every sense, including the religious; the mysterious breaks into an otherwise ordered and lawful world. Not so incidentally, the first image of the film proper is the steps of a rooftop ladder.

The film upsets its world of the 1950s: enlightened, rational, progressive, surpassing, even discarding, the past. In Vertigo, this is the rational world of Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes), in which a brassiere is designed by an engineer like a cantilever bridge. He, incidentally, works “down the peninsula” (Silicon Valley?). The phrase is later used to describe the mysterious San Juan Bautista, the mission church where the final catastrophe takes place.

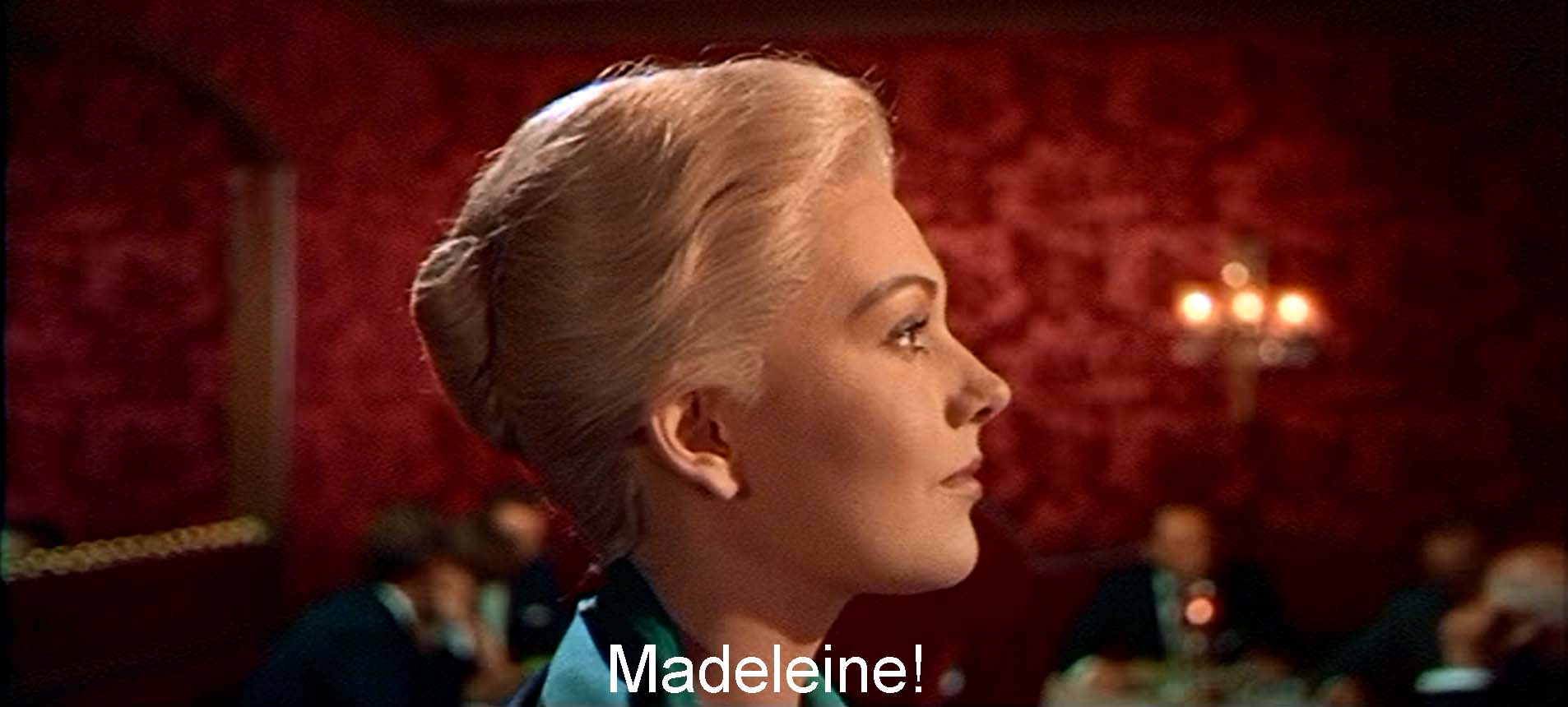

The premise of the film, Wood writes, is a man who has faced death, Scottie, a police detective (James Stewart). At first, after being rescued from the rooftop where he is precariously hanging, he tries to pick up his life again, logically, step by step, on the ladder in Midge’s apartment. Then he is offered something else: mystery, the supernatural, a life beyond death. He is offered, in short, Madeleine, the Magdalene, the woman who opens for him the mysteries of love. (Critic Tim Dirks points out that her initials M E raise the whole question of identity: who is she, really?)

The opening chase sounds one theme like a prelude: Scottie’s fear of heights leads to the death, not of the criminal, the guilty man, but of the policeman trying to rescue Scottie, an innocent, even a hero. The theme is Scottie’s guilt, irrational, undeserved guilt.

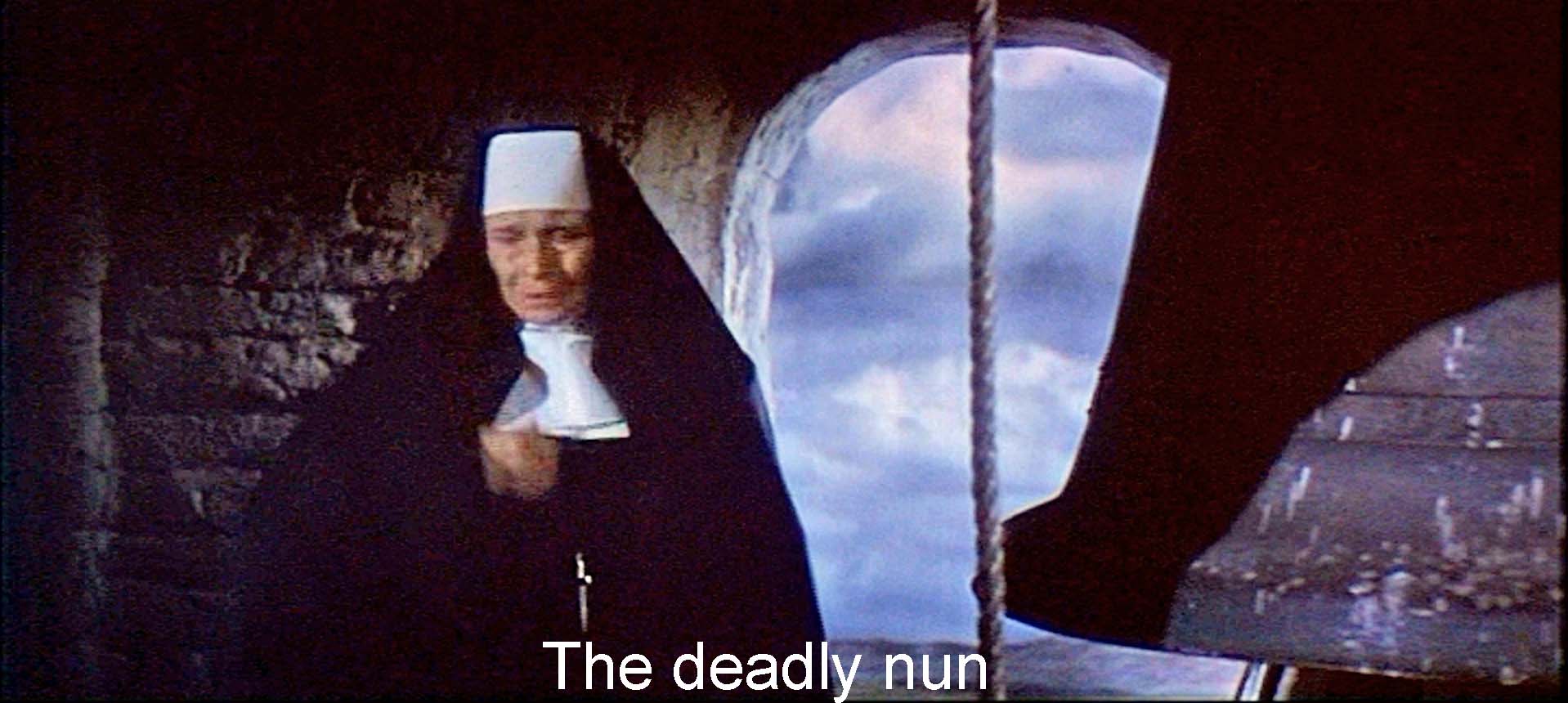

Then, throughout the first two parts of the film, Scottie’s two women square off around the question of what’s rational. Midge is the rational human, who doesn’t for a minute believe a ghost from the past is taking over Madeleine Elster. She laughs at the idea. Madeleine (Kim Novak) represents that irrational idea as not only possible, but as actually happening. She embodies the mysterious. Judy (also Kim Novak), through whom the villain created Madeleine, should de-mystify the mysterious, but only makes it more mysterious. As I read the film, by their last night together, Judy and Scottie might put their relationship together again on an honest basis. In the last moments of the film, however, a nun breaks into the film frame. The mysterious breaks into the rational again—and Judy falls from the tower, for a non-mysterious death this time.

Hitchcock’s own cameo appearance seems to me to bear out Wood’s reading. (I think one can show that all of Hitchcock’s signature appearances in his films “fit” their themes—at least as I interpret them.) He walks across the film frame, carrying a trumpet case, as Scottie is about to go upstairs to the shipyard office of the villain Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore). I read Hitchcock as marking the move from one world to another. He is a Pied Piper, leading Scottie away from the realistic world, where, as “hard-headed Scot,” he has just been trying rationally to overcome his acrophobia. He enters the mysterious world that Elster will build for him. Elster’s office, Wood says (112), takes us from enlightened modernity in Midge’s apartment to a fantastic past (indicated by Elster’s models of sailing ships) in which men had the freedom and power to use women and throw them away.

If I follow out Wood’s reading, in the first third of the film, Scottie is himself the rationalist. He tries to overcome his acrophobia rationally. He tries to correct Elster’s apparent delusion. He tries to persuade Madeleine that “There’s an answer for everything.” In the second third, he is in a mental hospital, overwhelmed by his guilt and mourning—irrational forces. In the last third, he is lost in mystery, but we know what he doesn’t know. He, not we, submits to the irrational, the mysterious, only to find what we have known since Judy Barton’s soliloquy, namely, that it was not irrational at all. Restored to rational understanding, however, he suffers the same loss again, now in a truly mysterious way—because of the nun, who breaks into the scene. “I heard voices.”

My summary cannot capture Wood’s complex and subtle treatment of many details. What I carry away is his general idea. It gives me a way of reading the film that makes intellectual sense of many details. What it does not do is give me a way of coping with the flaws I see in this film.

I feel I discovered this film. As if it were my child, I want it to be perfect. I resent its flaws, and they are many and obvious. For example, how did Scottie get down from the roof? A loose end. Another is the visibly artificial color process, Technicolor distorted in some way. In this, as in many of Hitchcock’s movies, he uses process shots: he photographs some action against a projected background, so that the studio doesn’t have to make an expensive set or shoot on location. These scenes look fake when the projected background doesn’t match the colors or the contrast ratio of the rest of the scene. Hitchcock, I think, lets that happen deliberately.

In Vertigo, I sense such a mismatched process shot when Scottie and Madeleine kiss by the cedars of Monterey, itself a movie cliché. Scottie’s mute driving around San Francisco as he trails Madeleine Elster, often seems equally “off.” Yet the off-ness fits. It adds to the strangeness and unreality of mysterious Madeleine. Hitchcock keeps me in two different states of mind. In one, I think I am watching a fake, a fiction, an untruth. In the other, I feel as though it’s real because I am involved, and I want to know what will happen next—I care. It feels all the realer because he plays on my memory with familiar San Francisco landmarks: Coit Tower, Lombard Street, I.Magnin, and so on.

The key process shot—and, of course, this one is deliberate—occurs when Scottie has finally, utterly re-created Madeleine in Judy. He kisses her passionately, totally. The camera circles the kissing couple, focused on them, romantic music soaring. The background, however, changes from the pale green of Judy’s hotel room to the black wood and leather of the stable at San Juan Bautista where Scottie last passionately kissed Madeleine. Hitchcock is using the unreality. Intellectually I get the idea that the two women are now one. Emotionally, at this moment of love triumphant, I feel dizzy and confused.

The most important flaw in the film is, of course, the whole murder plot itself. "He planned it so well. He made no mistakes." Nonsense! It’s preposterous. Who on earth would hatch this incredible scheme to murder his wife? All this fakery so that people will believe Elster’s wife fell off the mission tower? What ever happened to old-fashioned blunt instruments or the taste-free poison? Why not hire a killer instead of a detective?

How could Gavin Elster be sure that Scottie would fall for Madeleine or that his vertigo would outweigh his love for her? How could he possibly be sure that Ferguson would not look at the first Madeleine’s body after it fell from the tower and realize this was not his Madeleine? Ferguson is, after all, a detective. He has fallen in love with Madeleine. And he won’t look? How could Elster be sure Judy playing Madeleine wouldn’t slip up somewhere? As she does in the last part of the movie.

I find myself thinking how absurd all this is. But I think that after the movie is over, not during it. It is Hitchcock’s art, his genius, to sucker me into belief. He displaces my attention from Elster’s plan, which we do not learn about until two-thirds of the way through. He focuses me instead on the possibility that a dead woman from the nineteenth century is taking over a live one. He gets me to believe that.

Is probability that important? Is realism? Verisimilitude? Many great works of art aren't realistic. Think of Paradise Lost, The Divine Comedy, The Tempest, The Waste Land, and on and on. What matters is perceiving a work of art as a work of art, and, psychologically, realism only matters if you make it matter.

I think what Hitchcock is doing is encouraging my projection into the film. We have fifteen minutes of dialogueless film as Scottie circles after Madeleine’s green Bentley, seeing her follow out the life of the nineteenth-century woman, Carlotta Valdes. All that time, I watch as Scottie watches. I wonder, as he wonders, What the hell is going on? There is no critique, no “voice of reason.” I'm not asking, Is this probable? I believe.

Hollywood these days tries to make us believe by elaborate make-up or computer-generated special effects or quadraphonic sound. This ultimate in realism puts a finis to projection. The current Hollywood “product,” the “McMovie,” as Harvey Greenberg calls it, leaves no room for our imagination. Today’s thriller or horror film acts out a fantasy realistically. But, by doing so, they limit us to that one fantasy.

Hitchcock, by his unrealities and improbabilities, gets me to judge them. In doing so, I participate in the movie and, ultimately, project into it. I fill in its lack of realism with my own imagination. Let’s face it, most people nowadays, brought up on a visual diet of commercial television, never develop much sense of unreality or imagination. By contrast, Hitchcock mobilizes my brain to believe even improbabilities, and we have to make an effort to disbelieve. We have to try deliberately to recognize that the movie is an illusion. That way, Hitchcock gets me to help create the movie, to project my wishes into it, my wish that a Madeleine not die, but go on immortally. My denial of death.

I think Hitchcock gets his emotional effect (as opposed to the cognitive one) by his use of “the uncanny.” Freud gave a prescription for eerie or “horror” effects in films and stories in his remarkable 1919 essay, “The Uncanny.” Hitchcock elicits belief and consequent fear in Freud’s terms exactly: by presenting some infantile or unconscious fantasy as if it were actually happening. Wood’s reading—the irrational breaking into the rational—sets the film precisely into Freud’s formula.

In Vertigo, the fantasy is the belief that one is being possessed by the dead, the child’s fear of walking past the cemetery. That is, after all, a kind of version of the normal mourning process, of (in psychoanalytic jargon) introjecting the lost object, less formally, not “letting go.” In effect, Madeleine is introjecting and identifying with a lost object, Carlotta Valdes. Then in the second and last thirds, Scottie cannot let go of the lost Madeleine and tries to re-create her. He tries to repeat. Here, Hitchcock shows us the dead possessing the living, forcing them to repeat some former life. This fantasy, when it seems to be repeating in reality, can be terribly, terribly spooky.

This is a picture which is essentially about many different forms of repetition. The image in the opening chase sequence of Scottie’s looking down past things repeated is the central image of the picture, because the picture itself, the plot, is built on a twofold structure, where the first episode, which comes to an end in the middle of the picture, is repeated in a sort of horrible way in the second episode of the picture. Then there are other repetitions in the picture. During the screen credits, Hitchcock triggers the idea of repetition by a series of spirals and Lissajous figures which are, after all, repeated figures whirling around on the screen. Martin Scorsese commented on Bernard Hermann’s famous score for Vertigo:

Hitchcock’s film is about obsession, which means that it’s about circling back to the same moment, again and again. Which is probably why there are so many spirals and circles in the imagery—Stewart following Novak in the car, the staircase at the tower, the way Novak’s hair is styled, the camera movement that circles around Stewart and Novak after she’s completed her transformation in the hotel room, not to mention Saul Bass’ brilliant opening credits, or that amazing animated dream sequence. And the music is also built around spirals and circles, fulfilment and despair. Herrmann really understood what Hitchcock was going for—he wanted to penetrate to the heart of obsession.

The most important repetition Hitchcock creates is the film’s double plot. It hinges on repetition, but there are odd little incidental repetitions. For example, at one point Scottie and Madeleine go out to a redwood forest, where they look at a cross-section of a redwood tree, seeing the various rings of the redwood tree, which again suggest the succession of seasons, a repetition of things in time and space. Scottie’s friend Midge is a sweater-and-skirt type. But all the sweaters are the same kind of sweater, the same monotonous design of cardigan, just in different colors. Midge creates a portrait of herself that repeats the portrait of Carlotta in the art museum.

Another element repeated in the picture is water. The villain is a shipbuilder—he makes she's— and this associates him with the water. A lot of the critical scenes of this movie take place in or around water. The wave surface of water suggests repetition. Then, too, water in a Freudian sense is one of the powerful symbols for birth and mother. And mother is a powerful repetitious force in our lives.

Midge, Scottie’s college girlfriend, represents another repetition. According to the psychoanalysts, every woman a man falls in love with after his mother will have something to do with her. When [Midge] says to Jimmy Stewart, “Just call me mother,” she is reminding you of the repetitious power of family in our psyches.

I can read Vertigo in terms of the “triple goddess.” This is an idea popularized by Robert Graves, and it figures prominently in Jungian criticism. I first encountered it in Freud’s essay on The Merchant of Venice and King Lear, “The Theme of the Three Caskets.” Mythologists point to the repeated occurrence in myth and legend of triads of women: the Gorgons, the Graces, the graiai, the moirai (Fates), the Norns, Macbeth’s “weird sisters,” and so on. Often, the triad follows the pattern of the Fates, the first associated with birth, the second with the course of life, the third with death—in T. S. Eliot’s phrase, “birth and copulation and death.” Sometimes the triad follows the related pattern of a virgin or spring goddess, a mother or harvest goddess, finally a crone or death-goddess. Persephone in her six months on earth, Demeter the goddess of fertility and harvest, Persephone-the-destroyer in her six months in Hades. Sometimes they follow the pattern of virgin or unattainable love, the lush, sensual woman, the old woman.

The pattern occurs over and over in fictions, and it occurs in Vertigo, which is, most of us would say, a film much about women or Woman. “Mother’s here,” Midge says to Scottie in the mental hospital. She identifies herself at least three times as “mother.” By contrast, Madeleine is an idealized image of woman, like a goddess, a Venus. The deadly third woman is the nun, dressed in black, who causes the death in the finale. She echoes Carlotta Valdes who also burst into Madeleine’s life (supposedly).

Midge is altogether different, the woman to relate to, to talk to, to be friends with. Madeleine is the woman to look at. Indeed, Scottie looks at her naked after he fishes her out of San Francisco Bay. (Death and rebirth? Botticelli’s Birth of Venus? A baptism? The fatal mission is called San Juan Bautista.) The nun is the woman we don’t see, the woman in darkness and shadow. So is Carlotta Valdes, another destroyer (supposedly).

In the film, Scottie realizes that Judy and Madeleine are one when Judy puts on the red jeweled pendant that had supposedly been Carlotta Valdes’. I see a contrast between that bloody red and the greens that Hitchcock deliberately associated with Judy/Madeleine: Madeleine’s and Judy’s green dresses; the green soft-focus effect associated first with Madeleine, then with the remade Judy; the green neon sign flashing outside Judy’s window; the giant redwoods, sempervirens, always green.

Red and green. Stop and go. Green and go occur with looking, fantasizing, with the unreal and ideal woman from the past. Red and stop occur with sexuality or the genitals, the moment when the ideal woman is discovered to be the low, sluttish woman or vice versa. In other words, the recognition scene in the movie acts out the same split in male sexuality that Madeleine and Judy do: the ideal, unreal woman and the available, sexual tramp. The cliché is “Madonna-whore.” The mirror in that scene splits Kim Novak in two, as so many mirrors in this film have done. Then the film undoes that split. The two kinds of women are one, and that is a horror.

A red oval jewel with ornamentation around it, hanging down—as so often in Hitchcock’s work, the symbolism is “Freudian” and a bit obvious. Interestingly, we never see Madeleine wear that jewel, although Elster tells Scottie, “When she is alone, she takes them [Carlotta’s jewels] out and handles them gently.” We see the pendant in Carlotta’s portrait. We see it in the mock portrait Midge paints of herself in the role of Carlotta. And, of course, at the climactic moment of the film, we see Judy wearing it. It is as though we can have the red object on the other versions of Woman but not on the idealized goddess.

Hitchcock, I think, is playing in this film with my emotions about my mother. He uses the anxious combination of the ideal love one feels (or felt) toward a mother and one’s feelings toward a woman announcing her sexuality. That is the love (or lust) Scottie feels for Madeleine, and evidently he has never before experienced this kind of total love (or lust) as an adult. It is total commitment. She is an ideal, cool, aloof, mysterious, a goddess.

Madeleine is a woman located in past generations like a mother, but she is also now. There is a hint of eternity about her. She is both all-powerful and helpless, needing to be rescued from the spirit that is possessing her. She is the woman-to-be-looked-at, the goddess on a pedestal, one of Hitchcock’s blond heroines like Madeleine Carroll. The very first image of this film, before the credits and spirals, is a woman's face.

I think we are seeing something about Hitchcock’s idea of woman. The “royal road” to Hitchcock’s psyche, it seems to me, is the changes Hitchcock did and did not make in his source. Vertigo is based on a novel, D’entre les morts (From Among the Dead) by the two French writers, Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. They had written the screenplay for Diabolique, as scary a movie as movies get. According to François Truffaut, in his book of interviews with Hitchcock, they wrote this book precisely for Hitchcock. They were not on contract. They just hoped he would option it and make a movie of it, and he did.

Some things Hitchcock took over directly from the novel. He kept the basic plot. A husband gets rid of a wife by involving a friend with a woman playing the role of the wife, who then is killed. In the novel, the villainous husband’s name is Gévigne. This becomes Gavin in the film. Hitchcock also kept the name Madeleine. She is the Magdalene, the woman Christ transformed from a prostitute to a saint. Medieval paintings show Mary Magdalene as a penitent with a box of ointment or reading alone before a tomb or a skull. The film shows her that way when she sits before Carlotta Valdes’ portrait holding a bouquet.

Some changes Hitchcock made simply to suit American audiences, like changing from Paris-Marseilles to San Francisco. Others are more ingenious, like using the same church tower for the two deaths.

One major addition Hitchcock made was the Midge character and the whole plot associated with her. Entirely Hitchcock’s, she is the rational foil to the fabulous, mysterious Madeleine. Midge is the non-ideal, an available woman, the woman to relate to as an equal or even to patronize a bit, the gal next door, a pal. “Mother’s here.” She is the woman Scottie has apparently outgrown, a woman who would like to be seductive and sexual, but is cozy instead.

Both Madeleine and Midge contrast with the sluttish Judy Barton who lets us know that many men have tried to pick her up (and some succeeded). Midge draws brassieres for a living, and both she and Madeleine are well girded in the bra department. Kim Novak, however, Hitchcock told Truffaut (248), took particular pride in not wearing a bra when she was playing Judy Barton.

Hitchcock, as I read him, is playing with a powerful tension I felt, perhaps all men and women feel. He plays off an idealized goddess-mother-woman against the later, more realistic mother, necessarily less the total possession of the infant. He gives us two versions of that later non-ideal, one asexual (Midge) and one sexual (Judy). Judy is or was the father-figure’s (Elster’s) woman. Hitchcock had originally planned to use Vera Miles for Madeleine/Judy, he told Truffaut (247), but she “became pregnant.” “After that I lost interest.” “I couldn’t get the rhythm going with her again.”

If I read the film for what it did for Hitchcock, I find an image of his wish fulfilled. As Donald Spoto points out (275), Hitchcock in making Vertigo is like Pygmalion, an artist creating the perfect woman to show up the deficiencies of ordinary women. Here, the ideal woman is secretly the sexual woman, and the sexual woman can be turned into an ideal. Not the merely “nice” woman. When nice, pure Midge shows him the picture of herself as Carlotta Valdes, Scottie is disgusted, turned off, angry. The ideal has to be the sexual, even sluttish, woman. From her, Scottie (and earlier, Gavin Elster) made the ideal.

Guilt is another Hitchcockian change from the source. Many critics have pointed to the Catholic-raised Hitchcock’s preoccupation with guilt, particularly undeserved guilt. Here, he makes the Scottie character present at the first death (not so in the novel). He makes the falls take place from a church tower, with priests and nuns as witnesses. He adds a long, droning monologue by the coroner (wonderfully done by Henry Jones), stressing Scottie’s guilt (undeserved). He gives Scottie a guilty nightmare and a nervous breakdown. In the second death in the novel, the Scottie character himself kills his re-created love. In the film, Scottie is innocent, but who is going to believe him? That coroner? A man twice present when a woman he is involved with falls from the same church tower? No way.

There are minor Hitchcockian themes as well: “the woman with glasses.” In Strangers on a Train it is the repellent first wife (to be killed) and the homely kid sister (and Hitchcock cast his own daughter Patricia in that role). Here, there are two. One is the clerk at the McKittrick Hotel, who is evidently in on the plot. The other is Midge, who can't attract Scottie. There is something wrong with people with glasses, particularly women. They don’t “look right.” They are not pleasant to look at, and they themselves can’t look, and looking is terribly important to Hitchcock. In this movie, like many of Hitchcock’s, the core of the action is looking (think of Rear Window). Here it is looking at that goddess-like blonde.

Stairs are another Hitchcock preoccupation. Horrible things happen in Hitchcock movies at the top or the bottom of stairs—as in this film. Some critics have spoken of a “Hitchcock image,” a corridor, tunnel, or drain, some receding hole, anyway. Something goes into it and disappears or something scary comes out of it. Here we see it in Judy’s coming down the corridor or out of the bathroom when she is finally toute Madeleine, Midge going down the corridor at the mental hospital, above all, the look down the stairway in the church tower. As a psychoanalytic critic, I can’t help referring this to fantasies or memories of the primal scene (a child’s witnessing sexual intercourse). I would expect such preoccupations with a gifted filmmaker.

There is a famous effect in this film. Some have dubbed it “the Hitchcock shot,” It could be called the Vertigo shot. Three times he achieves the dizzying and disorienting effect of vertigo. We see it first in the opening when Scottie looks down and freezes, causing the policeman’s death. We see it the second and third times when he runs up the tower after Madeleine. In the final shot, however, looking down from the tower, Scottie does not have vertigo. This shot, and Judy/Madeleine's falling down cancels out the opening, a succession of men climbing up onto a roof. Scottie has been cured, but at what a cost!

Hitchcock had wanted to do such a shot for a long time. After fifteen years (and some technological innovations), he realized he could do it by zooming the lens in (increasing its focal length) and dollying the camera out at the same time. Why did he obsess about it for fifteen years? Perhaps because one goes in and out at the same time, both closer to the subject and more distant.

Hitchcock carried over some of the larger elements of the novel unchanged, like the trip to the cemetery or the old hotel. He also took unchanged some of the smallest details from the novel such as the “gray suit, very tight at the waist” (Boileau and Narcejac 1956, 25), “severely cut.” (28). But the Madeline of the novel is “dark and slim” (20), with “dark hair discreetly tinted with henna” (23), “abundant hair which seemed too heavy for her face” (20). Hitchcock’s transcendent Madeleine is one of the luscious blonde women who step through his films in almost endless procession: Madeleine Carroll, Joan Fontaine, Marlene Dietrich, Janet Leigh, Doris Day, Tippi Hedren, above all, Grace Kelly.

Scottie, who hung from a rooftop, re-creates the goddess Madeleine from the tarty Judy (as Christ, the Hanging Man, transformed the Magdalene). But Scottie is only re-creating. At the end we learn that Gavin Elster was the first to create the blond goddess from the tramp. (Robin Wood cleverly points out that Elster is a shipbuilder, ships are she’s, Elster is a she-builder.) But even Elster was not the first.

That was Hitchcock himself. As he said of Vera Miles, this was “the part that was going to turn her into a star.” It is Hitchcock who will create the blond goddess. When he chose Novak, he annoyed her by making her set her hair and wear clothes in ways he liked and she didn’t.

Hitchcock’s contempt for actors was legendary. “Actors are cattle,” he is said to have said. In later years, I’ve read, he would drive up in his Rolls Royce, check out the scene he had meticulously storyboarded the previous night, then drive off, leaving the actual shooting to his assistant. To be sure, he had elaborately and meticulously sketched out the whole scene on paper the night before. But even so! Where is the direction of the actors? Actors for Hitchcock were not supposed to act, they were just supposed to be there. “James Stewart,” commented Truffaut (111), “isn’t required to emote; he simply looks—three or four hundred times—and then you show the viewer what he’s looking at.”

What gives Hitchcock’s actors their emotion is the Kuleshov effect (Holland 1989) It’s not their acting, but the surrounding situation. And that Hitchcock controlled totally.

Consider Kim Novak’s acting, about which critics (and Hitchcock himself) have had their doubts. Take the scene after the supposed drowning, when she comes out of the bedroom. Seeing the movie the first time, you think she’s embarrassed because Scottie has seen her naked. Seeing the movie the second time, you realize that Novak’s character was pretending to be unconscious and is now pretending to be embarrassed. The actress is pretending to pretend to be embarrassed. What a challenge! Wow! Terrific! And Novak carries it off! Or does she? Isn’t it the situation that clues us to read her behavior as a double-level pretense? The meaning of her acting depends on what we know of the circumstances around the event. It depends on what Hitchcock has set up, not what Novak does.

I think Hitchock’s practice is part of his world-view: people are at the mercy of their surroundings, dwarfed, for example, by Mt. Rushmore or the Statue of Liberty. I think that is why Hitchcock is drawn to psychiatric explanations, which are invariably over-simple (as at the end of Psycho or Marnie). In Vertigo, a psychiatrist describes Scottie’s breakdown as “acute melancholia together with a guilt complex,” labels that say nothing. I think Hitchcock uses such cookbook psychiatry to image people as controlled by circumstances. Psychiatric explanations are worthless, because the problem is deeper. If you are guilty, undeservedly guilty, the reason is in the universe.

My point is, that is why Hitchcock insisted on as much control over his films as he could get. He was the controlling circumstance. He was the god-like artist creating the blond goddess. “Miss Novak arrived on the set with all sorts of preconceived notions that I couldn’t possibly go along with,” he told Truffaut (247-8). “I went to Kim Novak’s dressing room and told her about the dresses and hair-dos that I had been planning for several months. I also explained that the story was of less importance to me than the over-all visual impact on the screen, once the picture is completed.” Exactly what Scottie does in the film itself.

Hitchcock wanted to look at that ideal blond woman. The operative word is look, something he shared with most male moviegoers and probably many women. (Nowadays critics talk about “the gaze.”) For example, there is a scene where, it is clear, Scottie has seen Madeleine naked. (I read his expression when he ministers as a possessive smirk, even a leer.) This being 1958, we do not see her nude. We infer what happened. (Hitchcock is using, as always, the audience’s projection.) Conversely, according to Hitchcock,

Cinematically, all of Stewart’s efforts to re-create the dead woman are shown in such a way that he seems to be trying to undress her, instead of the other way around. What I liked best is when the girl came back after having had her hair dyed blond. James Stewart is disappointed because she hasn’t put her hair up on a bun. What this really means is that the girl has almost stripped, but she still won’t take her knickers off. When he insists, she says, “All right!” and goes into the bathroom while he waits outside. What Stewart is really waiting for is for the woman to emerge totally naked this time, and ready for love (Truffaut, 244).

Truffaut comments simply, “That didn’t occur to me.” (And he a Frenchman!) It didn’t occur to me either, and I think Hitchcock’s idea that he is undressing Judy has more to do with his fantasies than anything we are seeing on the screen. (It has been suggested to me, though, that that final bun is another symbol for the female genitals—golden this time.)

Re-creating Madeleine was evidently the fun of the film for Hitchcock. It is for me, too, and so is looking at the cool elegant Madeleine during the first third, as it probably was for Hitchock. Then there are two other moments that trouble me, that make me feel distinctly uncomfortable.

In one, Midge cheerily shows Scottie the portrait she has painted of herself in the role of Carlotta Valdes (complete with the fateful red jewel). She expects him to laugh along with her and get past his obsessive belief that Madeleine is being possessed by a dead woman. Instead, he is repelled. Mild Johnny reacts strongly, rejecting the picture—and her. His harsh words are, I believe, the last words he speaks to her in the film. She cries bitterly over her foolish attempt at a joke after he leaves. Why was it so awful?

The other discomfort comes right after Scottie has seen Judy Barton on the street. He comes up to her hotel room and begs her to have dinner with him. She finally says yes. Right after that, Hitchcock lets us in on Judy’s secret. She starts to write Scottie a confession and farewell, but changes her mind. It is at this point that we learn what Gavin Elster’s plot was and how Judy abetted him in it.

Telling us the answer to the mystery two-thirds of the way through is Hitchcock’s most brilliant stroke in Vertigo. The novel explains the mystery only in the last pages. Hitchcock’s team all told him not to do this, and some early reviewers complained of it, but it is a genuine stroke of genius. From that moment, we know what Scottie doesn’t know and Judy does know. As Hitchcock put it—

The truth about Judy’s identity is disclosed but only to the viewer. . . . that Judy isn’t just a girl who looks like Madeleine, but that she is Madeleine! Everyone around me was against this change; they all felt the revelation should be saved for the end of the picture. I put myself in the position of a child whose mother is telling him a story . . . . In my formula, the little boy (sic), knowing that Madeleine and Judy are the same person, would then ask, “And Stewart doesn’t know it, does he? What will he do when he finds out about it?” . . . . We give the public the truth about the hoax so that our suspense will hinge around the question of how Stewart is going to react when he discovers that Judy and Madeleine are actually the same person (Truffaut, 243).

In other words, the focus changes. We shift from staring at the blond goddess to a much more human problem: What will happen to Judy when Scottie finds out?

Both the episode of the fake portrait and the revelation that Judy is Madeleine feel uncomfortable to me. I understand the portrait episode as asking me to identify Midge with the fantasy woman. The confession shifts me from re-creating the gorgeous Madeleine, too beautiful to be real, into the real relationship between Judy and Scottie. I think it is because both moments lead me away from the fantasy I enjoy, looking at this perfect woman, too beautiful to be real. Both moments ask me to relate instead of look.

One way I see this film is as this man’s, Scottie’s, two relationships to women. Perhaps it is about all men’s relationships to women—or Hitchcock’s. Perhaps it is only moviegoers’ relations, entranced by these ideal figures on screen who can so contrast with our everyday lives. Perhaps it is “about” the psyche of the typical moviegoer, at least the male moviegoer. Perhaps it reaches women because both genders have the same early emotions toward a mother. Once she was the ideal and she necessarily ceases to be. Or perhaps I am linking the film to a man’s wish for a lover who would submit completely, give up all, even identity, and expect nothing in return. Perhaps I see the film as about the way such a wish limits and subverts real love, such as Scottie might have had with Midge. It is a wish that limits Scottie, limits Elster, limits Hitchcock, limits me.

Why, then, do I feel this is such a “great” film? I know it is, because I can show (to my own satisfaction, anyway) how beautifully articulated it is, how every moment contributes to the unity and complexity of the whole. But why do I feel it is?

I think I feel it is because the film allows me a sweeping denial. Scottie can deny the impossibility of a woman from the past taking over a living person (something realistic Midge never for a moment believes). Because Carlotta Valdes is responsible, he is freed of his responsibility for the “death” of the first Madeleine.

The snide coroner, however, in his nasty, nasal monologue (entirely Hitchcock’s addition) insists on Scottie’s responsibility. “Mr. Ferguson” failed to acknowledge the realities of the situation, Madeleine’s apparent illness and his own vertigo. He is guilty, guilty, guilty.

Scottie has a nightmare and breaks down. Somewhat recovered, he wanders the streets looking for his lost love, until he meets Judy and, mournfully, re-creates the lost Madeleine.

My own feelings as he re-creates Madeleine are: Why not? He has managed the impossible. He has managed to create or re-create this gorgeous movie star woman. She loves him. Why not enjoy it? Why not love her, have an affair, whatever? The fantasy woman is made real.

Scottie begins this movie as a failed detective. He is wearing a corset, thus feminized, leaning on a cane, unable to climb three steps, unable to sustain a sexual relationship (his failed engagement to Midge). This weak man is not only able to create the ideal woman, he even possesses her (in the fadeout after Judy appears with Madeleine’s hairdo).

Then, in the final moments of the film, miraculously, Scottie is not guilty! Sure, everybody will think he is, but he isn’t really. He is not an unrealistic, demanding, unfeeling lover whose deficiencies lead to the death of the loved one. No! He was the victim!

The film feels “right” to me because I can intellectualize about it and interpret it. It feels “profound” to me, though, because it has dealt with a psychological issue near the center of my own being: denials leading to finalities, the failure of relationships, even to death. Denials of the unreality of someone like Madeleine, a denial that limits and subverts real love.

Denial triumphs. I have canceled the guilt, changed the years, undone the loss, turned back time, denied denial itself. I have achieved (in fantasy) the goddess-woman-mother. I have achieved that power and freedom men speak of three times in the film, the power and freedom to use women and toss them away. Elster, Scottie, Hitchcock with his total control of star and film—and now me, the critic attaining the power and freedom I envy in the artist. And I pay just enough of a price, the death of Judy/Madeleine, revealed now as the guilty party, so that I am truly freed. At least for the 129 minutes of Vertigo. And maybe you are, too, and maybe many others, and maybe that’s why so many critics and ordinary viewers have found in Vertigo a masterpiece.