Can music be cynical? Anton Karas’ zither score for this film is legendary. Reed added it after the shooting, after he happened to hear Karas play at a Vienna club. He insisted on it over his Hollywood distributor’s wanting to provide the conventional thirty-piece concert orchestra. And it made the movie, this simple folk strumming with scarcely a melody in what would be the right hand if this were a piano melodies tunes and the sly, insinuating accompaniment (what would be the left hand if this were a piano). Yes, I think it is cynical, and it embodies the moral ambiguity of this Vienna and this film.

As with Carol Reed’s other masterpieces, Odd Man Out and The Fallen Idol, he made a film thick with competing moralities, particularly his favorite value, loyalty. Producer Alexander Korda needed to use up some money locked in postwar Europe. He chose Vienna for a setting and sent Graham Greene over to get ideas for a screenplay. Greene arrived in a city still divided into four zones, each controlled by one of the victorious powers, Russia, France, the U.K., and the U.S. British intelligence officers told him about the penicillin racket, and an Austrian journalist explained how the vast network of sewers let criminals circulate under the zone boundaries. Greene used what he had learned to write a novella and, working with Reed, the screenplay, focusing on the moral issues in this corrupted city.

Korda made a deal with David O. Selznick, somewhat benzedrine-addled at this time, for the American distribution, and Selznick intruded on the production in various unhelpful ways. (Cary Grant as Harry Lime? Barbara Stanwyck as Anna?) He cut 11 minutes to make a sanitized American version. Today, we watch the original, acid British film.

It opens with a description of Vienna by an unknown speaker (Reed’s voice). “I never knew the old Vienna before the war, with its Strauss music, its glamour and easy charm. I really got to know it in the classic period of the black market.” Classic? I would have thought the “old Vienna,” was the classic, but this is all part of the ambiguity. “We’d run anything,” says this speaker, “if people wanted it enough.” “We”—evidently he himself ran black markets. He goes on to explain the four-power system, and his comments and the images of old and blackmarket Vienna that go with them tell smart moviegoers that this is a film about dividedness. Old and new, Hapsburg grandeur and rubble, military discipline and sordid black markets, the four powers, competing values, contending loyalties . . . As always, the opening shots tell you what the movie is about. The divided city mirrors the dividedness within the characters.

This is a film rich in moral ambiguity. People lie. They seem to be telling, but they aren’t. Throughout, people spy on other people. There are wary sidelong glances, looking without looking. And what are we in the audience doing if not trying to ferret out the characters’ secrets?

The prologue introduces us to the hero, if he can be called that, Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten), one of the blundering innocents that Reed so enjoyed. Holly writes cheap Westerns with titles like Death at the Double X Ranch or The Lone Rider of Santa Fe. He brings to ambiguous Vienna a clean-cut American morality of good-guy bad-guy, black-and-white. That’s why he totally misunderstands the Viennese situation. He walks under a ladder without noticing. He speaks no German. He can’t even get the names of people straight. He manages, over the course of the film, to mess up everything he comes near, even or especially his lecture for a literary group. He foolishly falls in love and tries to help the woman, Anna, but he fouls that up as well. By the end, he has caused the deaths of two people who were trying to help him and the deportation of the woman he loves. He even gets his finger bitten by a parrot. A spooky little boy who fingers Holly for the murder of the porter, echoes Holly. He too is a naïf who causes trouble out of his ignorance and blundering. And Holly betrays his childhood friend, his best friend who was trying to help him. As Anna says, “ I loved him. You loved him. What good have we done him. Look at yourself, they have names for faces like that.” Anna is loyal, Sergeant Paine is loyal, even Anna’s kitten is loyal—but not Holly.

Holly’s antagonist is wise guy Harry Lime, a school buddy who lured him into all kinds of childhood misdeeds. He brought Holly to Vienna partly out of kindness: to give him a job and money. In return Holly betrays him and kills him at the end (more moral gray). Together, Holly and Harry bring to Europe two kinds of Americanism: a naive moralism and profit-at-any-cost.

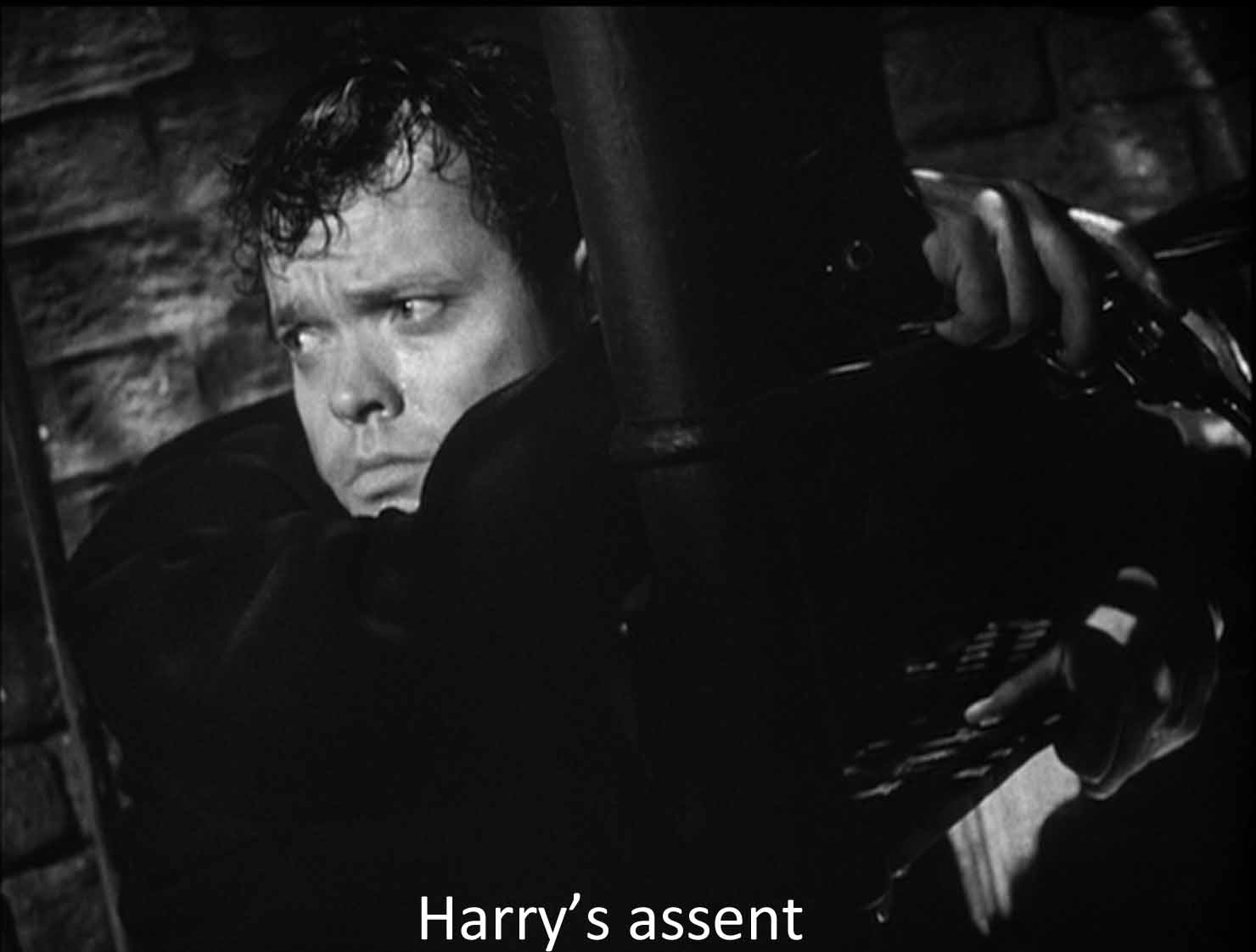

Harry Lime is, after Charles Foster Kane, Orson Welles’ greatest role. Welles didn’t want to do Lime at first because the character appears onscreen for only ten minutes. But then he realized it was what he called a “star role”: the other characters talk about you for an hour and then and only then you make your entrance. And what an entrance it is! Sardine paste on the shoelace so the kitten will nuzzle those polished wing-tips that are all we see of Harry Lime. It is one of the most famous entrances in all of cinema—and Welles wasn’t even in the shot; it was the assistant director in the bulky coat and shiny shoes. The next shot, the close-up of Welles’ mischievous face, was done in London.

But what a ten minutes it is! The speech everyone remembers (Welles' inspired improvisation, not in Greene's script) is: "In Italy for thirty years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, bloodshed—they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, five hundred years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock." This is all part of Harry’s roguish charm (that played on in a long series of radio shows). As Anna says of the man she loves, "He never grew up. The world grew up around him." And Welles does have a kind of impish baby face in this film, echoed in the porter’s spooky child.

But people don’t remember what came before the cuckoo clock, the dialogue that states the deepest moral ambiguity in the film. Holly and Lime are at the top of the famous Riesenrad, the big Ferris wheel in the Prater amusement park. Holly, fresh from Major Calloway’s show of what Lime’s crimes have done to children, says, “Have you ever seen any of your victims?” “Victims?,” says Harry. “Don’t be melodramatic.” He points to the people far below. “Look down there. Would you feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving forever? If I offered you £20,000 for every dot that stopped—would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money? Or would you calculate how many dots you could afford to spare? Free of income tax, old man, free of income tax. It's the only way to save money nowadays.” That sounds grandly cynical and brutal, and it is. But think about it. Why should the death of strangers concern us? And does it, really?

Moral indignation comes easily to Holly (and to us) after Calloway's demonstrations of the children maimed by Lime's diluted penicillin. But think again. Think of the massive March 1945 bombing of Vienna that created the wreckage we see in the film: 747 US bombers, 1,667 tons of explosives followed by the Red Army and a total of 37,000 Russian and German dead. Think of the bombing of Berlin or Hamburg or Tokyo, as part of our “good war,” our “just war,” the one Calloway callously calls “the business.” How many children were maimed in those good deeds? As Philip Kerr argues, “Greene seems to be asking us how morally reprehensible it is for one man to sell a few tubes of dodgy penicillin when others, such as Churchill . . . had so recently ordered the saturation bombing of Dresden to say nothing of what America had inflicted on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Does the death of strangers matter to us? Should it, really? Can it?

Harry, who, by the way, is Catholic, puts it this way to Holly: “You're just a little mixed up about things in general. Nobody thinks in terms of human beings. Governments don’t, so why should we? They talk about the people and the proletariat.” Do governments think of individual victims? World War II killed 50 million people at the behest of several governments. It is against such a war and such a world that one needs to hear Lime's speech to feel its full force. And the rubble of ruined Vienna keeps that war in our sight and in our minds.

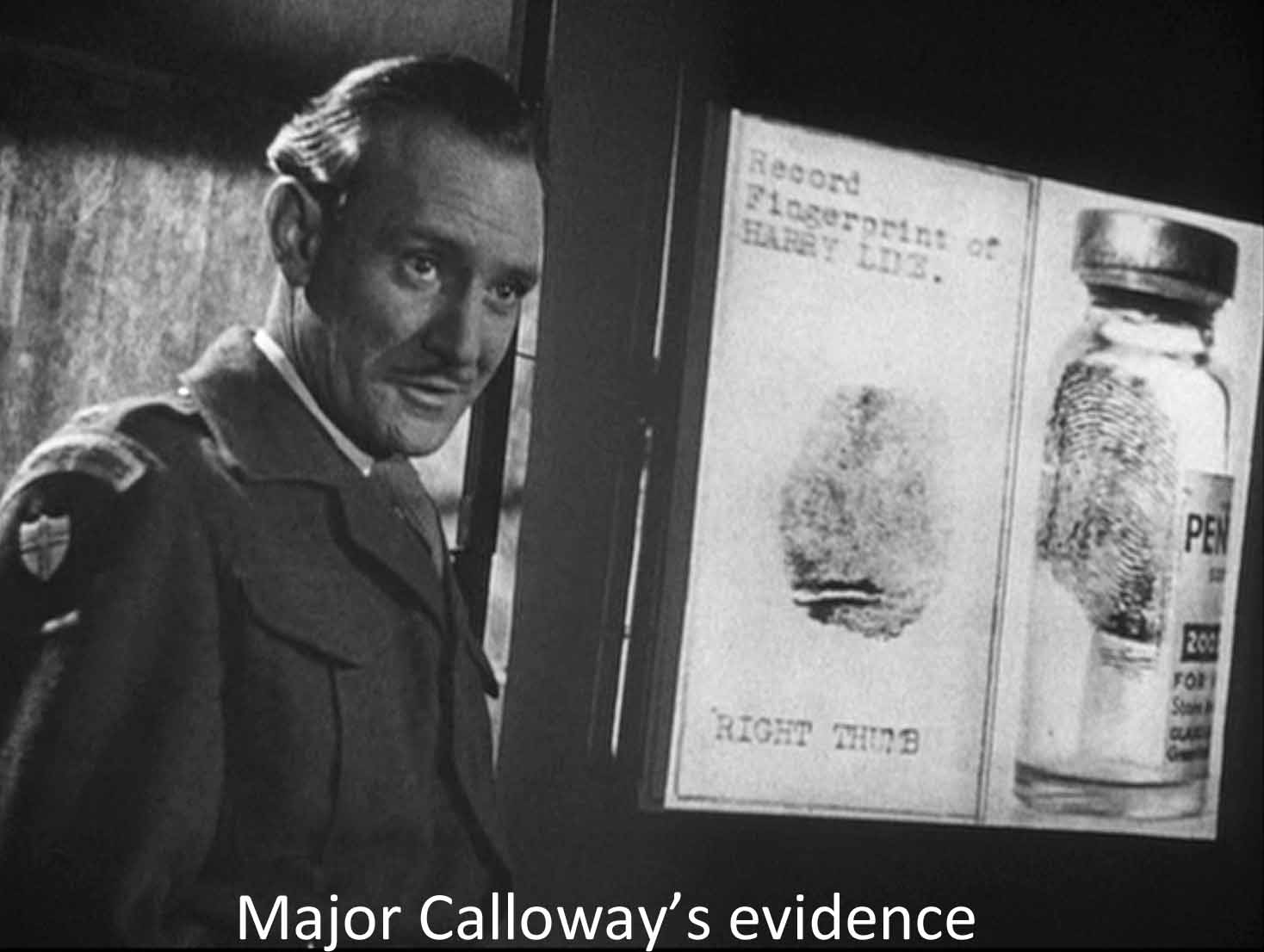

Poised against Harry Lime is Major Calloway. “Major” is the only first name he has, and he seems the very soul of incorruptible British morality and military rectitude. But he is always spying. He is perfectly willing to use Harry’s trust in Holly to get his man. And he is equally willing to use Anna as a bargaining chip and turn her over to a Russian gulag, if need be, to get Holly to betray his friend.

And that brings us to Anna. She is a classic Carol Reed woman, who must stand by and watch her men suffer. (Think of Kathleen in Odd Man Out or Julie in The Fallen Idol.) We know that Anna knows of Lime’s deadly racket. Calloway evidently told her all. But! “A person doesn't change because you find out more,” she says. Anna seems to embody the moral value E. M. Forster proclaimed: "Between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country." But that is hardly a moral certitude: Calloway exemplifies the opposite. Does she realize that it was Harry who tipped off the Russians? And what is the use of her rejecting Holly’s saving her from the Russians? What is she trying to prove? Her love for a rat? Her preference for Harry over Holly?

Notice, too, how the characters put forth their different moral stances. Calloway uses visuals, with practically no explanation. Anna acts out her disapproval by walking out of the film frame. Holly proclaims his loyalty to his friend in a lot of drunken jabber—talk. They each give us one of the modalities of film: actions, sights, talk. And then there is Harry. He puts forth his ethic of selfishness in the slickest, most memorable speeches of the film. For the two Americans, morality is all talk.

Back to Holly: in the conversation on the Ferris wheel, Lime draws a heart-and-arrow on the glass with the name Anna. Why? One should remember that, the previous night, Harry was standing in the street below Anna's window looking up. He hid when he saw that she had a visitor, a visitor carrying flowers, and he knows the visitor was Holly. That is why he draws the heart-and-arrow on the gondola window: he's needling Holly. Are you really so moral? Aren't you chasing my girl?

Not only the four principals but some minor characters are all morally doubtful. Obviously, Lime’s fellow racketeers, Kurtz, Popescu, and Winkel, follow his creed of profit whatever the cost. But even Crabbin, the cultural functionary—we see him hustling his mistress out of sight.

Other minor characters seem driven by moral imperatives. The porter feels he must tell Holly what he can—despite his wife’s cagey warnings. Sergeant Paine plays out loyalty to his boss. He and the other soldiers, including the Russian are “following orders” or “following protocol,” even when they don’t know what “protocol” means. Even the spooky child feels impelled to accuse the man he thinks murdered his father and pursue him down the street, as do the others in the crowd who follow him. His murdered father is probably the only completely straight character, and he gets killed for his pains (no pun intended).

The crookedness of the characters shows in their names. Lime—slime? And Lime is Green—Greene? Graham Greene’s famous preoccupation with moral failure? Lime is in the limelight. And here’s a strange fact: the plot the film makers used for Lime's grave is now occupied by a man named Grün, green in German. Anna Schmidt is obviously not her real name. And she keeps calling Holly Harry (Freudian wish-fulfillment). Sergeant Paine administers pain when he knocks Holly down. “Holly, what a silly name,” says Anna. (It comes from Thomas Holley Chivers, a minor nineteenth-century poet of the American “graveyard school.”) Holly himself has a lot of trouble with names, calling Calloway Callahan, not knowing James Joyce, calling Winkel “winkle.” “Winkel” means "angle" in German, with the suggestion of something crooked or twisted. “Winkle” as an English verb is the process of wriggling a periwinkle, also a “winkle,” out of its shell. “Kurtz” means short in German, but it’s also and famously the name of the morally berserk colonist at the heart of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Crabbins—crabbed? Is the Rumanian Popescu some kind of Pope?

The ultimate strangeness, I think, is the possibility that Lime might be a Christ-figure. (Reed was always alert to Christian possibilities.) Here Lime dies and is resurrected: death-and-rebirth. The title of the film may echo that episode on the road to Emmaus when two men were walking and the resurrected Jesus joined them and then vanished (Luke 24:13-31). When Lime first appears and escapes from Holly, he descends into the underworld (the sewer). Is this the “harrowing of Hell?” Then he rises again. The time scheme is a bit hard to follow but, as I see it, it is on the third day of Holly's stay in Vienna and the appearance of the third man that Lime rises in the Ferris wheel and then comes down to earth. And, finally, of course, he falls to the depths, dying in the sewer. Remember that the porter had hell above and heaven below when he first talked to Holly: this is a film in which the moral universe is topsy-turvy, in which, perhaps, even a Harry Lime can be a Christ-figure.

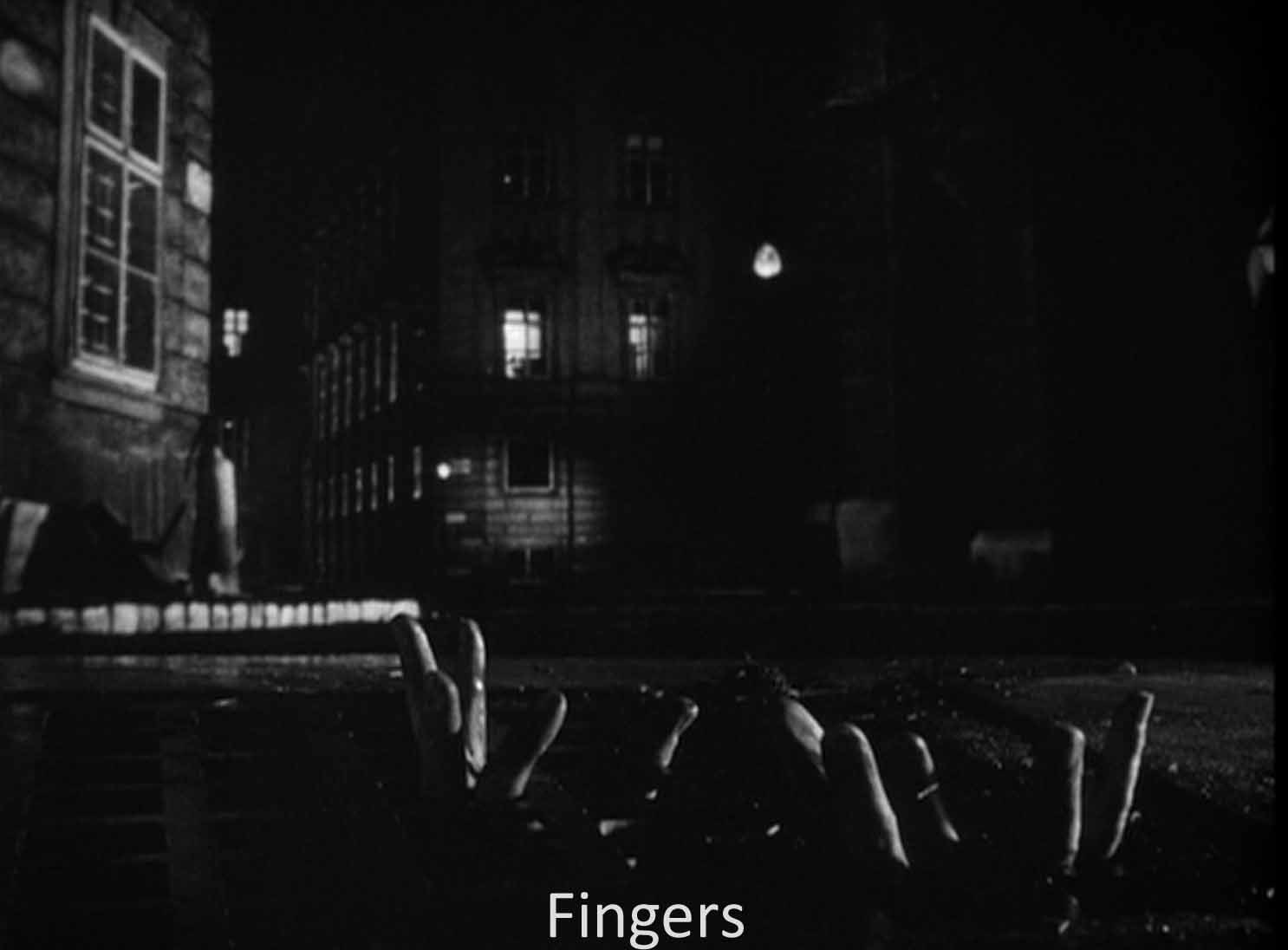

As in the porter’s speech (spoken from an upper floor), as in The Fallen Idol, Reed plays with verticality. The ill-fated porter, upstairs, tells Holly, downstairs, that hell is up and heaven is down. There are a lot of shots of people going up stairs, and By and large, people upstairs or going upstairs are, so to speak, up to no good. Notable are the teams of soldiers going upstairs to ransack Anna’s apartment or to arrest her (making her dress in front of them) or leading her upstairs to Calloway’s office. Holly stands above his audience at the literary lecture. Holly courts Anna upstairs, revealing himself to Harry hiding downstairs in the street. Then there is Holly’s talking from the street below to Winkel and the Baron on an upper floor. He demands to see Harry, and then we get Harry’s self-justification way, way up on the Ferris wheel (including a threat to throw Holly down). The seller of balloons floating up insists on interfering with the trap for Lime. Finally, Harry dies trying to escape up and out of the sewer—that famous shot of fingers reaching up through the grating (Reed’s fingers, actually!). It is as though the characters are groping toward some right level on which to live—the moral question in this film whose irony so remarkably combines moral gravity with airy cynicism, heaven below and hell above.

The hard, open-ended finale extends the moral ambiguity. Where do Holly and Anna stand as the film ends? Damned if I know. Greene wanted Anna to take Holly’s arm with the implication that they would have a romance. It was Selznick of all people who backed Reed and insisted that Holly and Anna could not get together at the end. It is this woman, immoral by the standards of the Hollywood Code, who shows the only personal, not institutional, morality in this movie: loyalty to someone you love. As Alida Valli walks camera right and out of the frame, she puts the seal not just on her character’s values but on a masterpiece.

The Third Man won the Palme D’Or at Cannes. The British Film Institute, rating all the British films of the twentieth century, named The Third Man number one. I think it is a film one can watch again and again without ever resolving its ironic combination of corruption and high morality, its cynicism, if you will.

The team of Korda, Greene, and Reed have achieved a masterpiece about moral and political ambiguity. And one should also applaud the chiaroscuro photography by the gifted Robert Krasker (Henry V, Caesar and Cleopatra, Brief Encounter, Odd Man Out). He won an Academy Award for this picture’s acutely detailed black-and-white lighting and photography, strenuously contrasty for the night and sewer scenes (those shadows!), indeterminately gray for the daytime. To give The Third Man a unique visual texture, Reed and Krasker supervised three separate camera teams, one each for day, night, and sewer, each filming for almost 24 hours a day. What people most remember about the photography, though, are the “Dutch angles,” the tilted camera in shot after shot after shot. These Reed insisted on. To be sure, the tilt suits. It signifies the skewed moral world of the picture, but it’s most unusual. The story goes that, after the shooting, someone (the crew? Korda? William Wyler?) gave Reed a carpenter’s level to use in his next picture.

And finally, that music. Musicologist Hans Keller gives it a formidable description:

The striking, indeed the only feature about this ‘tune’ is its submediant obsession which, avoiding an Aeolian insinuation, creates an extended appoggiatura, a suspense by a prolonged suspension, enhanced by the tonic-dominant bass as well as by the alternation of tonic chord and dominant seventh. The sixth is the inhibitory degree par excellence, because its opposition to the tonic is based on the strongest possible measure of agreement or tertium comparitionibus, including as only the submediant triad does the tonic third: hence the arch-inhibition, the interrupted cadence V - VI. Hence, too, the added sixth—a familiar jazz device—is the tightest ‘wrong’ note, a harmonic non-harmonic note producing (ceteris paribus) the most primitive kind of dissonant chordal tension.