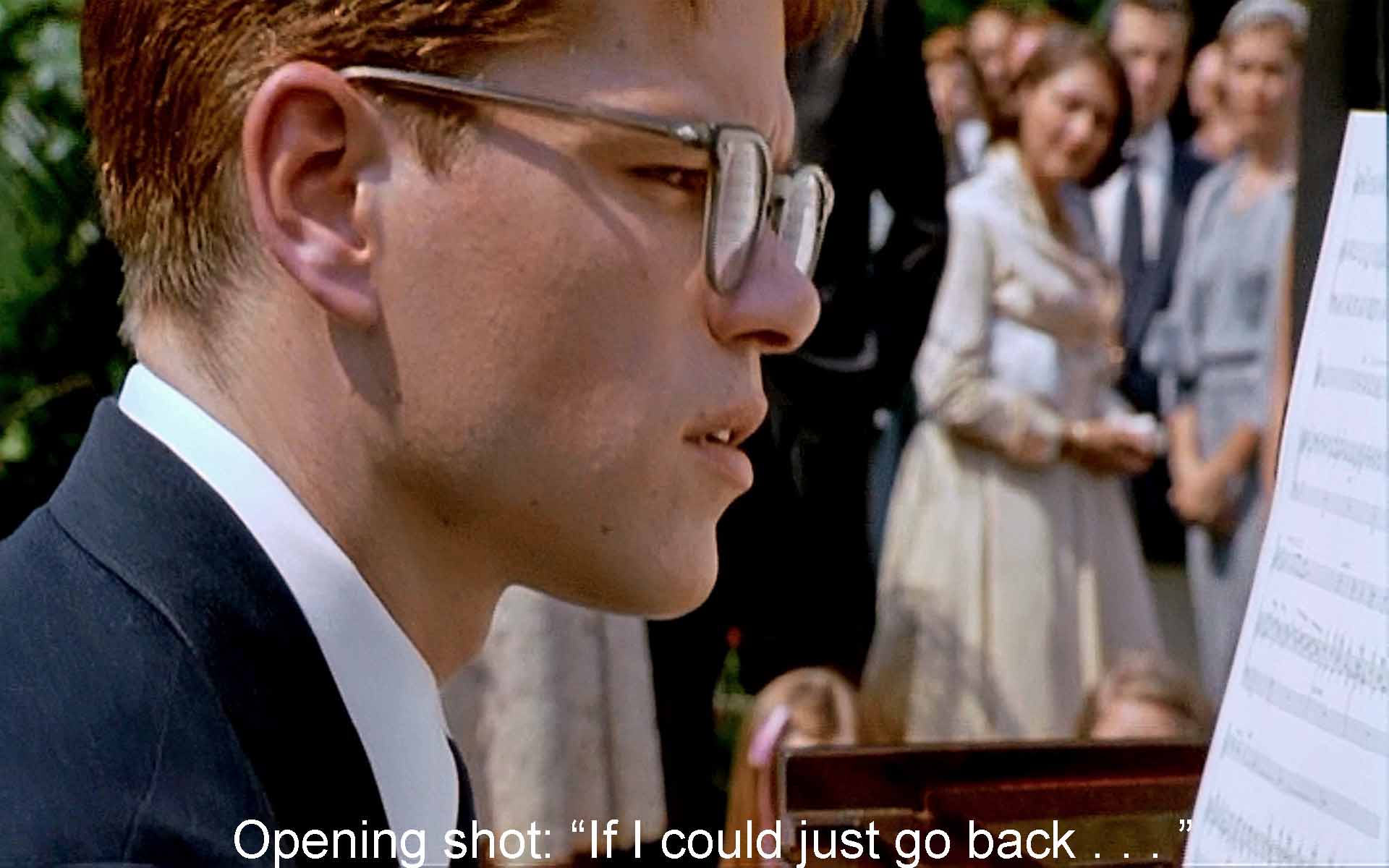

We start with an impoverished Tom Ripley (Matt Damon), working as a men’s room attendant in a concert hall, listening to and playing and loving what classical music he can sneak into. We end with a Tom Ripley who isn’t Tom Ripley at all, but rich playboy Dickie Greenleaf. From Ripley’s “Believe it or Not” to a new creation. Well not entirely new. It was Patricia Highsmith who created the original Tom Ripley as an anti-hero in five novels (the “Ripliad”). And before Anthony Minghella created a Tom Ripley in this film, René Clément had had Alain Delon embody him in Plein Soleil (1960).

The impoverished Tom happens to substitute for a friend, playing piano accompaniment for a young woman singing at an afternoon musicale. He also just happens to borrow his friend’s Princeton jacket. Mr. Greenleaf (James Rebhorn), fabulously wealthy shipyard owner, jumps to the conclusion that Tom must have known his playboy son Dickie at Princeton. Tom is everything his wayward spendthrift son is not: modest, unassuming, boyish, polite, subservient, fond of classical music, not jazz which is “insolent noise.” Would you, for a thousand dollars, go over to Italy and persuade my son to come home and go into the family business? (An ugly shipyard that will contrast with Dickie’s beautiful sailboat.) Tom agrees and preps for the job by studying jazz (which he doesn’t like). We’ve already heard the major theme of the movie: the improvised as opposed to the unimprovised; Dickie’s scripted future as opposed to his playboy shenanigans; classical music vs. jazz; Tom’s witty repartee and his cleverly adapting situations to his advantage.

All this takes place under the credits which end with Tom getting off the boat in Rome. Rich girl Meredith Logue (Cate Blanchett) greets him and says she is traveling under an assumed name. Tom takes the cue and tells her he is really Dickie Greenleaf using the name Ripley. From there the film proceeds through a dizzying series of improvisations.

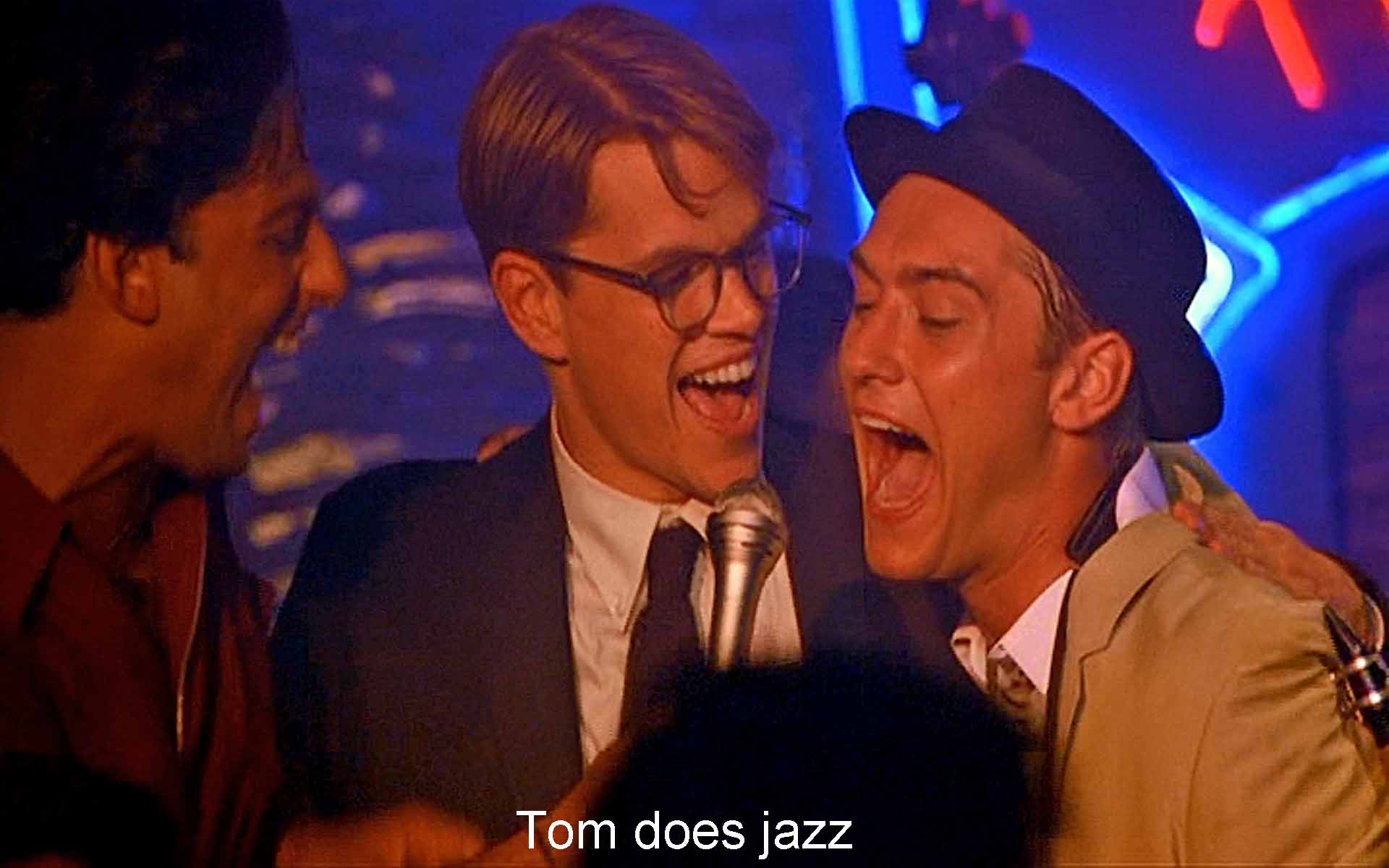

Tom makes his way to Mongibello, the little seaside town where the real Dickie (Jude Law) sails his beautiful boat, makes love to his fiancée (Gwyneth Paltrow), and has sex on the side with an Italian girl in the village. Despite Dickie’s rudeness at the start, Tom endears himself by his ready wit and by his ability to exactly imitate Dickie’s loathed father and by openly admitting his part in is father’s plan to get Dickie home. But above all he wins Dickie over by “accidentally” spilling a briefcase full of jazz albums and pretending to love the genre. At a jazz spot in Naples they sing (even shy Tom) the raucous Italian rock song, “Tu vuò fà l’americano,” a spoof of Italians trying to act American, another identity shift.

Tom, Marge, and Dickie form a happy triad. A fly in the ointment is Freddie Miles, a particularly repellent preppy who sneers at Tom’s plebeian origins, suspects his motives, and succeeds in getting Dickie away from him—for a time. (Philip Seymour Hoffman gives Freddie just the right touch of nasty.)

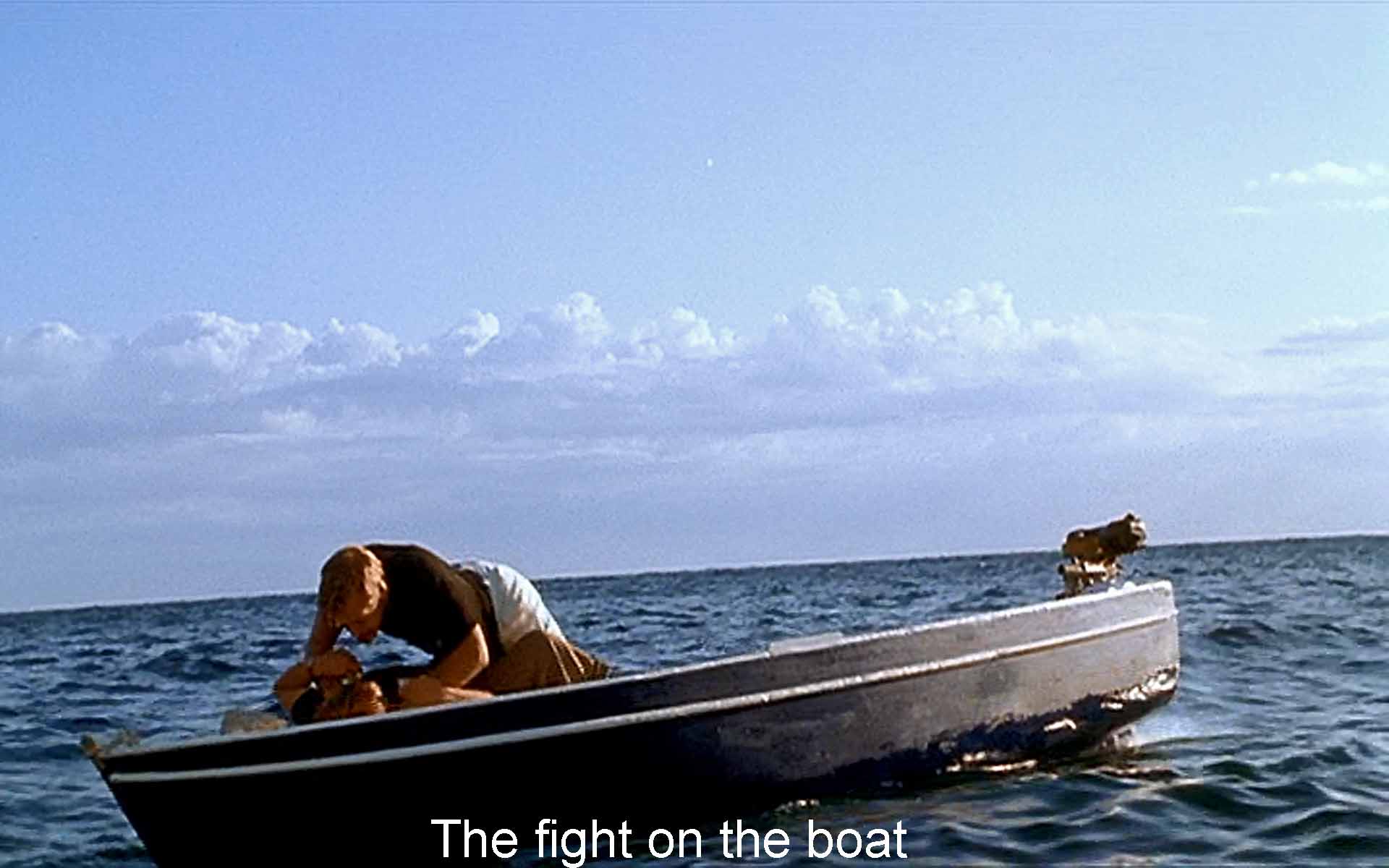

Another problem: Tom’s homosexual love for Dickie begins to become more and more obvious and disturbing to Dickie. Dickie finally tells Tom he wants to end the triad. The two of them go on a final trip together to scout out a new location for Dickie, and they go out in a motorboat. They begin to quarrel, and Tom shouts his jealousy of Dickie’s heterosexual doings. They fight, and Dickie is about to kill Tom when Tom kills Dickie.

Improvisation in jazz, improvisation in changing identities—that’s the major idea in this movie. Yet the music Tom loves is not improvisatory, but strict and ordered, string quartets, piano sonatas, and the opera. There he sheds a tear at Lenski’s aria before the duel in Eugene Onegin. Not only is he moved by his kind of music, but the scene echoes his killing of his best friend. It is at the opera that Tom’s improvisations almost fail. In a single hallway at the opera he is Dickie at one spot and Tom at another.

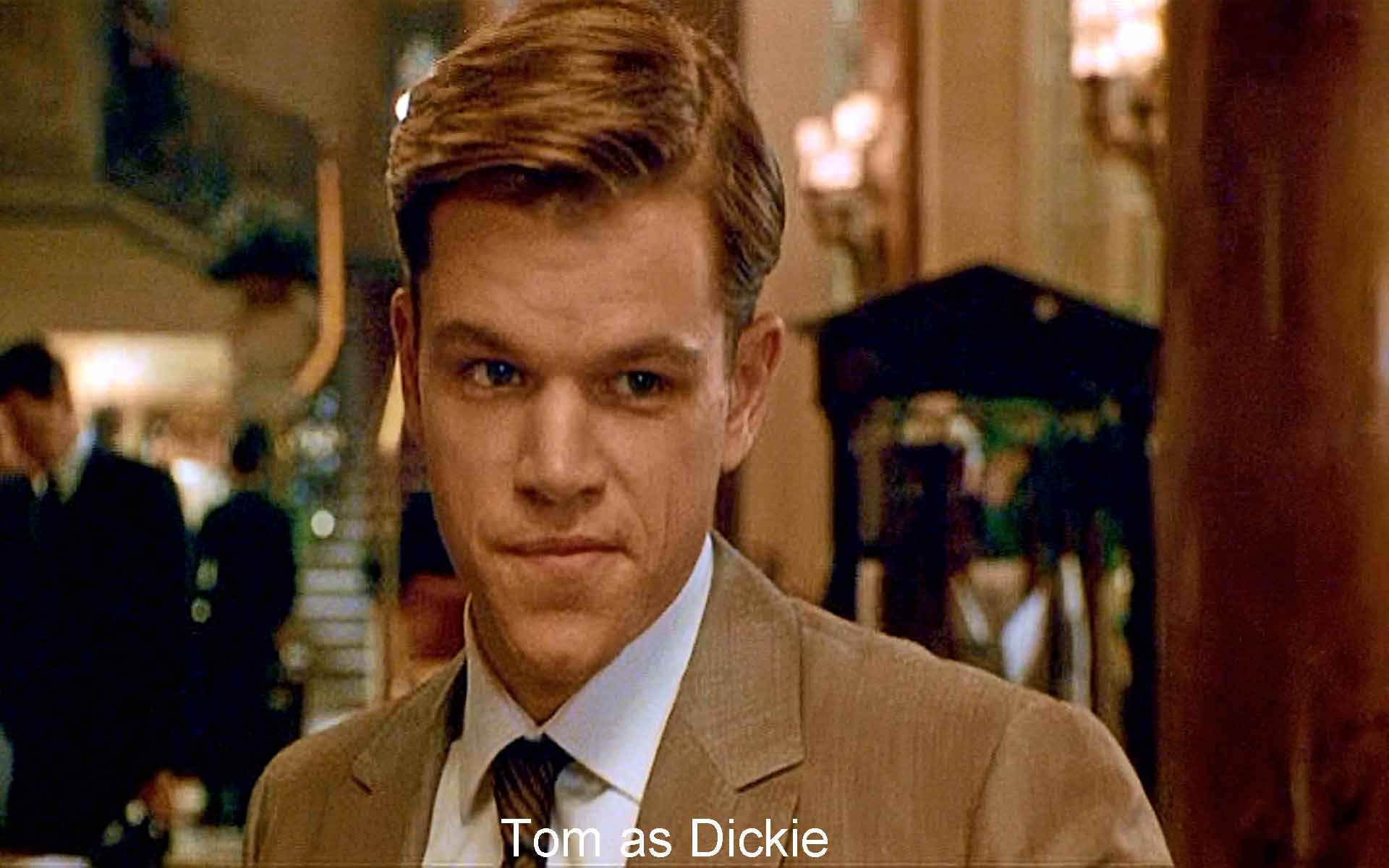

In the course of the film, Tom improvises a kaleidoscope of identities: men’s room attendant; serious, musical Princeton graduate; Princeton graduate who is a jazz-loving playboy; Princeton graduate who is a gay man with secrets; and finally Tom Ripley as Dickie Greenleaf. Tom is Dickie to the police in Rome investigating Freddie’s death, but he is Tom to the police in Venice. All this requires ingenious improvisations by Tom that put the jazz musicians in this film, fine as they are, in the shade.

Improvisation—that is one theme. Identity is another, a very American, 1950s idea of identity: that we are not limited by our birth, our economic class, our cultural level—only our skill and will. Tom states his credo, “I always thought it’d be better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody.” And he brings that transformation off by brilliantly improvising.

This is also a film about art and life: Tom’s piano; Marge’s novel; Peter’s cantata; and all the jazz. (Part of Freddie’s ugliness is his dislike of opera.) The art that Tom likes is not improvisatory at all, but it is jazz-like improvisation that enables him to achieve his ambition to become a “somebody.” It is at the opera that he meets Peter Smith-Kingsley (Jack Davenport), a handsome gay choral conductor who is obviously taken with Tom. They meet up in Venice and begin an affair of some weeks, culminating in a boat ride to a gig in Athens. But Meredith turns up on the boat, and Tom is Dickie to her and Tom to Peter—an impossible situation. The final shot shows Tom in his stateroom with mirrored doors closing on him. Boats and sailing are another theme.

Part of identity is gender and age, and part of this movie is a conflict between the old and the young, between men and women, and between the repressive society of the 1950s and the more open society coming soon in the ‘60s. While Dickie is clearly of the new, Mr. Greenleaf and the private detective he hires typify the male and parental superiority assumed to be “right” in the ’50s. Both these older white men curtly dismiss Marge’s all-too-accurate inference that Tom killed Dickie. Says the overbearing father: “Marge, what a man may say to his sweetheart and what he’ll admit to another fellow . . . “ “Marge, there’s female intuition and then there are facts.” “Marge doesn’t know the half of it.” And even Peter, young and gay, says, “She’s confused, and she needs someone to blame.” These men’s culture is relentlessly heterosexual with, as people say now, bi-valued ideas of gender. But identity is so variable in this film, and that’s very American. Ripley lives out the American dream of making yourself into what you want to be—but at what a cost!

This is a sad movie. Mr. Greenleaf loves his son—granted it’s love American style, conditional and business-fixated. But his love leads to his son’s murder. A villain gets away not only with murder but his victim’s money. The woman who loves him is silenced about what she knows. An innocent friend is suffocated. This is a linear film, none of the razzle-dazzle flashbacks and flash forwards that made Minghella’s The English Patient (1996) so remarkable. Patricia Highsmith created this likable psychopath who went on to other ambiguous successes in the Ripliad. And in the films that followed The Talented Mr. Ripley, he lives a pleasant life supported by occasional ventures into theft and murder, always successful, never much regretted. Minghella deserves much credit for starting him on that ambiguous career in this finely conceived film. He has said he wanted to surrender the film to Ripley’s own love of surface, beauty, and image—he succeeded admirably.