A train brings two newlyweds from a small town to Rome. The fretful husband, Ivan, is to introduce his dimwitted wife Wanda to his uncle and other relatives. The pompous uncle has “an important position” at the Vatican, and he and Ivan have scheduled every minute of this unromantic honeymoon. Highlighting their trip will be seeing the Pope. But Wanda has other plans. She has been devouring fotoromanzi, tabloids that use photographs to tell schmaltzy romance stories, here, the White Sheik, whom his harem girls love, and his enemy Oscar the Cruel Bedouin hates. Wanda adores the White Sheik. She has written him her love and gotten a letter back, inviting her to meet him in Rome. She is enraptured and now seeks him out. When she arrives at the seashore where they are shooting the series, she is swept up in the filming, induced to play Fatima the sexy slave girl who loves the sheik. A lecherous liar, the actor lures her out in a sailboat and tries to seduce her.

Meanwhile, thanks to the overflowing bathtub Wanda left behind her, poor Ivan has discovered his wife’s love letters. He starts rushing around trying to find his wife and to explain her absence to his stuffy relatives. The bourgeois family goes to the opera. We see them applauding Don Giovanni. as the baritone and soprano sing ”Là ci darem la mano.” It is precisely the moment when the lecherous nobleman is seducing the country girl on her wedding day. Ivan panics.

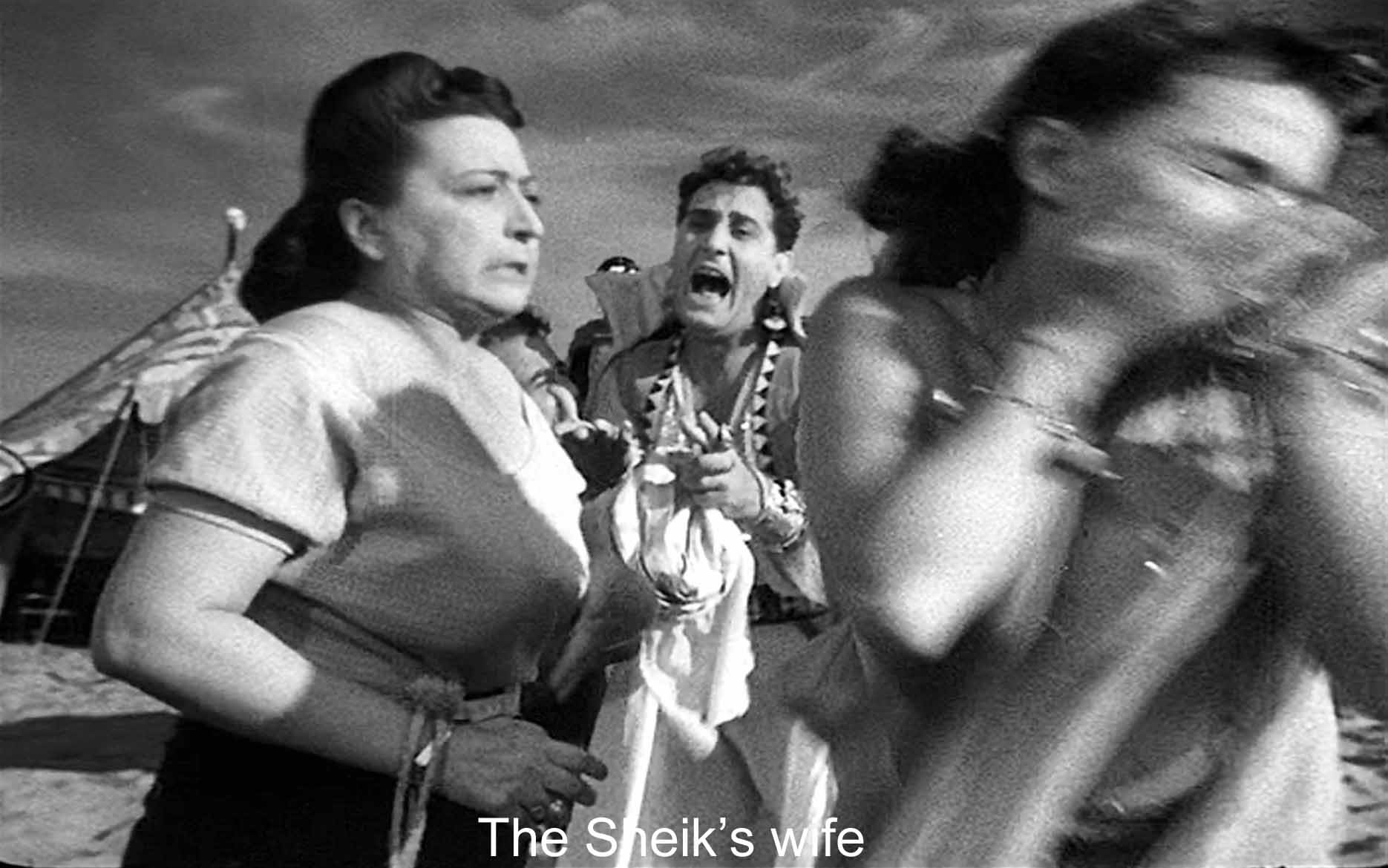

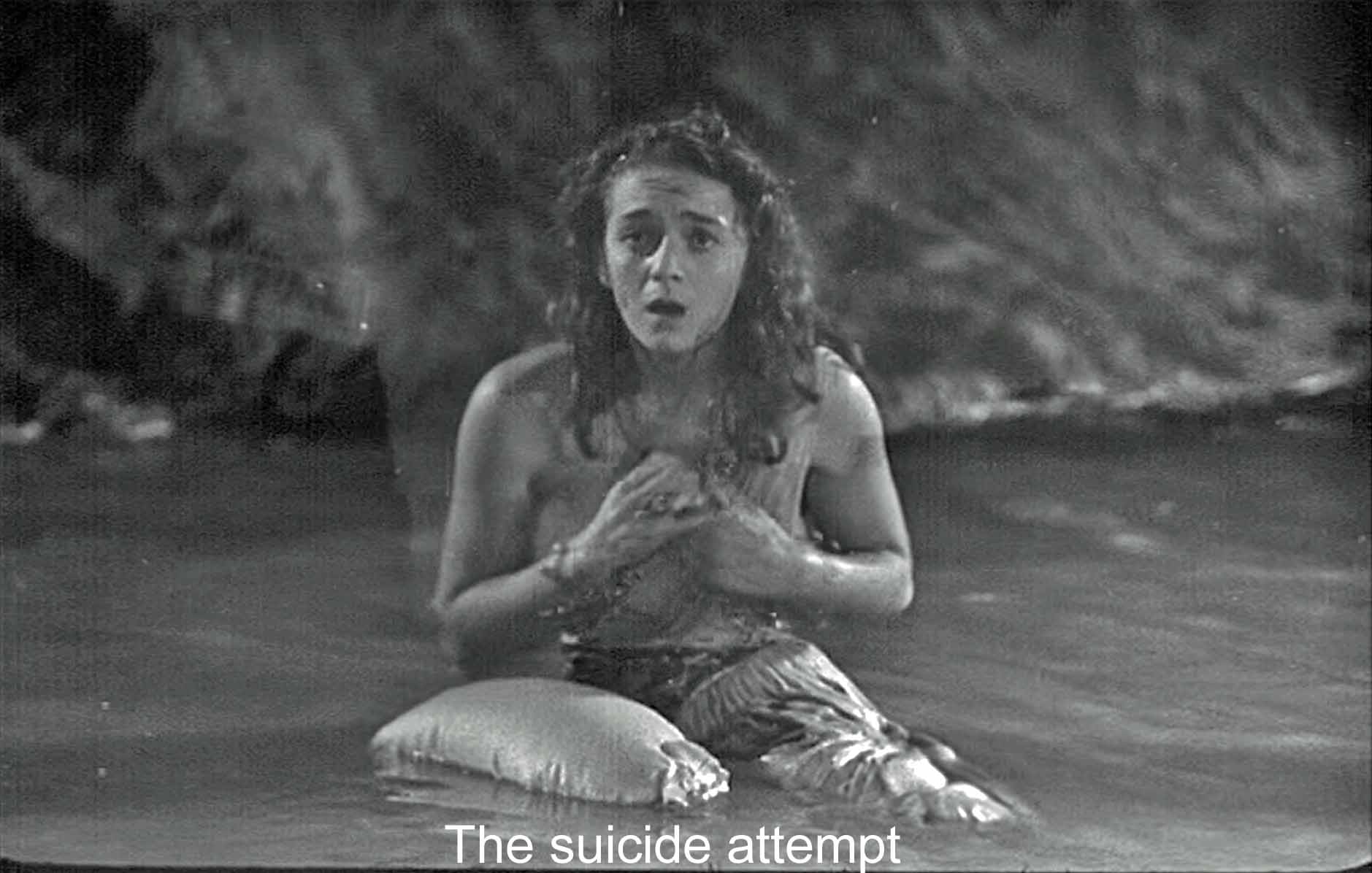

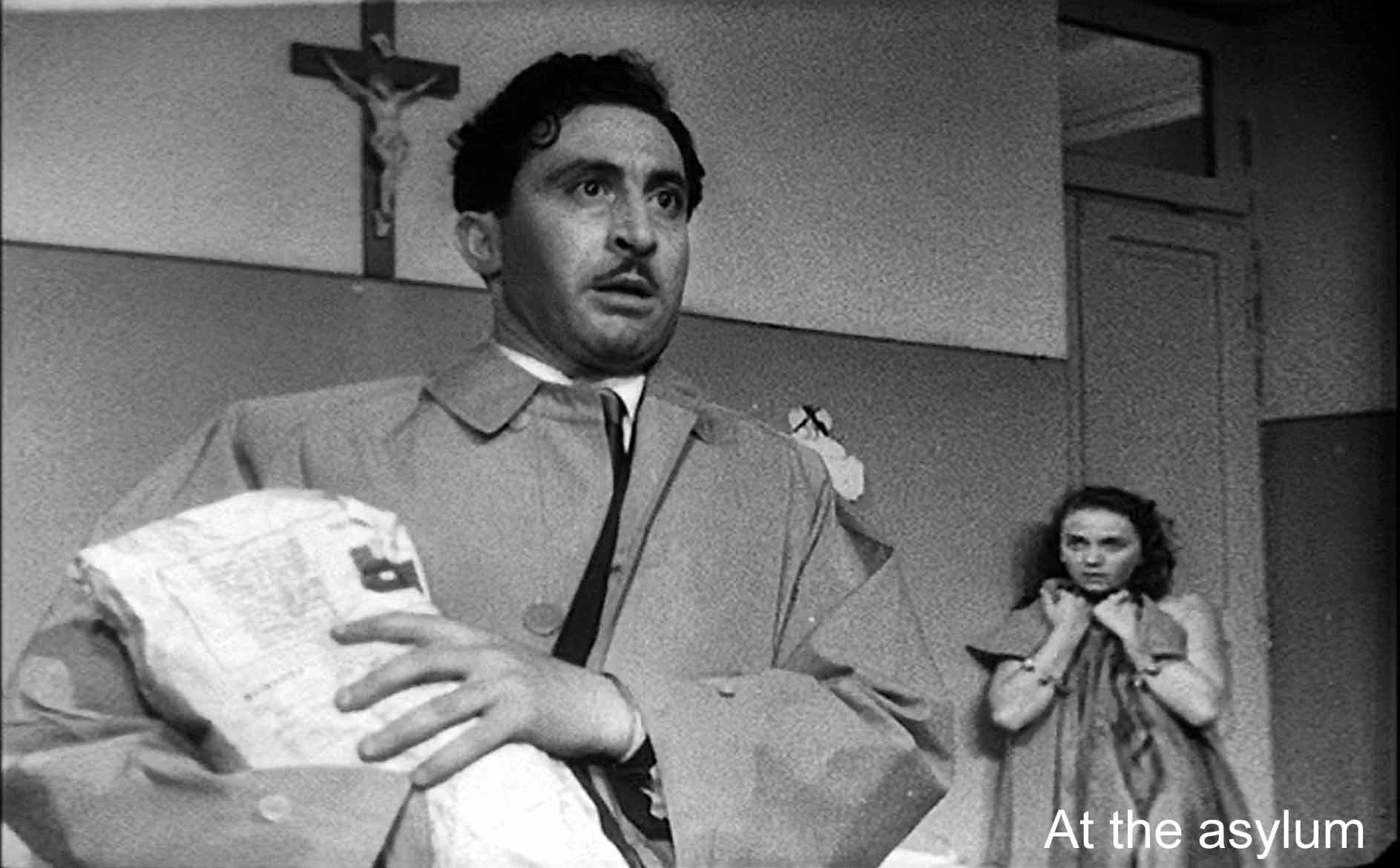

At that moment, in the world of the fotoromanzi, the White Sheik is fondling Wanda in a sailboat on the ocean. In the world of the bourgeoisie such goings-on are safely confined to the stage. Luckily, he fails, loses control of the boat, and they have to be rescued. The sheik’s termagant wife arrives and beats up on Wanda who flees. Delivered back in Rome, she attempts suicide, ineptly as she does everything, and she is taken to a mental hospital. There Ivan finds her, and just in time they join the relatives to see the Pope. A suitably happy (bourgeois?) ending.

Farce it is, but with an edge. Fellini is a satirist who is always both loving and laughing at the humans he makes fun of. The twitchy husband (Leopoldo Trieste), the witless wife (Brunella Bovo), the pompous uncle (Ugo Attanasio), the White Sheik himself (Alberto Sordi,) they are all ridiculous and hopelessly bourgeois (even the sheik), yet Fellini treats them with affection.

Fellini loved faces. He first worked as a cartoonist, and he kept caricaturing on paper all his life—and in film. Often he would introduce a face just for the sake of the face, here, an Ethiopian priest, a policeman, the hotel clerk, or various members of the film crew. One of my favorite moments in this film is a sequence where Fellini shows the faces one after another of his chubby Italians chowing down, then cuts to a camel whose mouth moves just as theirs do. And Fellini loves fat people. We fret about obesity in America, but no one seems to fret about pasta-eating Italians. And Fellini, no string bean himself, enjoys every pound of them. Humanity as freak show. Critics have noted that in every one of the 27 films he directed there is an episode in which someone performs. People often say that Fellini saw the world as a circus.

Here the circus is the eccentrics making Lo Sceicco Bianco, one of the two worlds of the film. That world is the crazy world full of funny-looking characters doing preposterous things. Incidentally they drive the director of this semi-film, perhaps a stand-in for Fellini himself, crazy. Their opposites are the unfunny bourgeois, the self-important uncle, his squawky wife, the aunt and her fiance (an accountant! he proudly tells us) and the kid Arnolino who seems sharper than the rest. Both Ivan and Wanda quickly do what they are told. He in particular gets caught in groups of marching men (a habit left over from fascism?). One world is moralistic, capitalistic, Catholic, obedient. The other is amoral, impoverished, and wacky.

The two worlds define two roles for women, roles acted out by Wanda. In the capitalist, bourgeois, Catholic world she is to be wifey, submissive and faithful to her husband, living her life as the shadow of his. But in the fotoromanzo world she is free to pursue her dreams and her lusts as Fatima the sexy slave girl devoted to the sheik. But, of course, that has to collapse—comically and a little sadly. She does, after all, try to commit suicide.

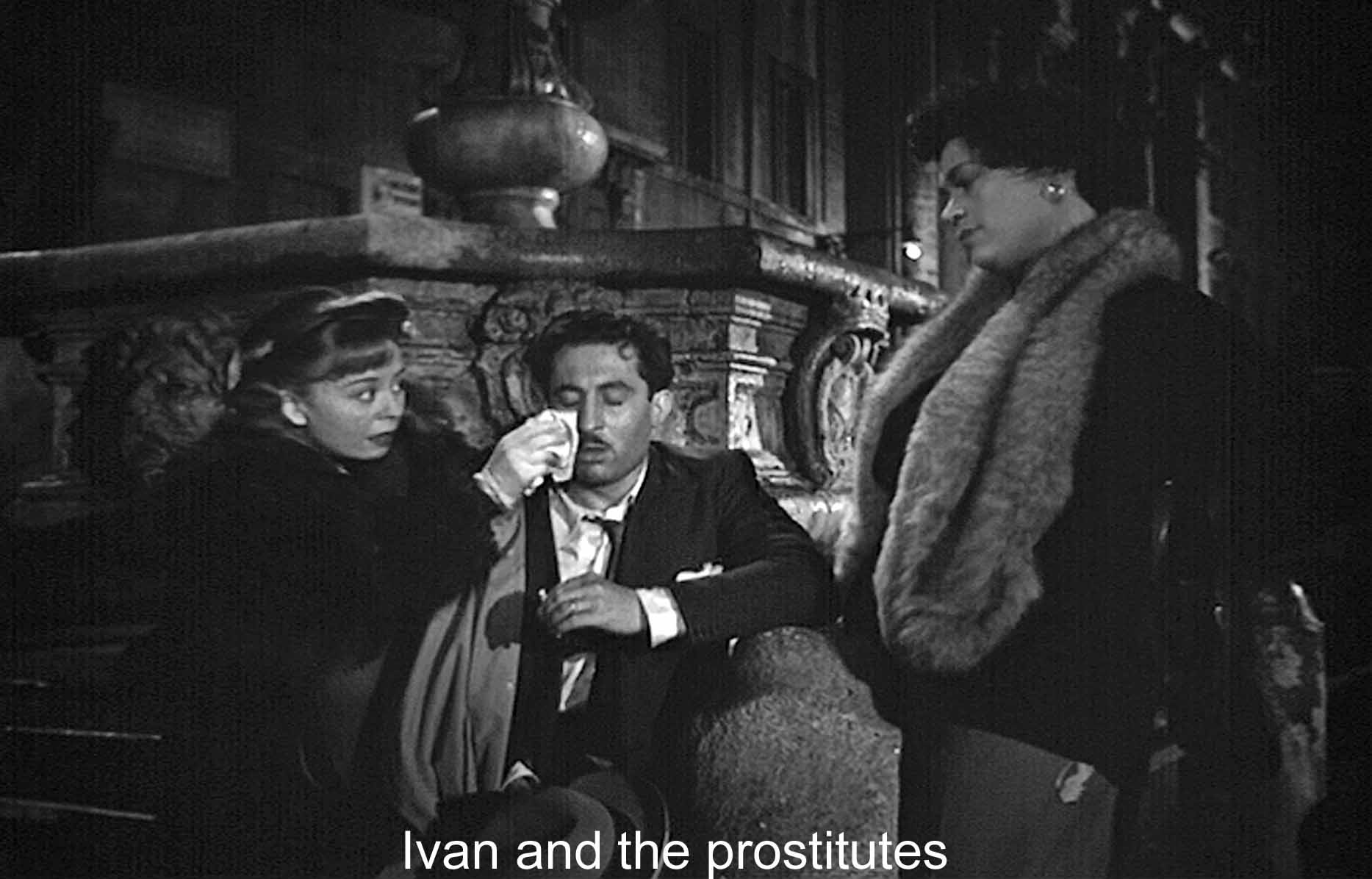

She tries to drown herself (in about a foot of water), the third time water is important: the bathtub, the ocean, the Tiber. Often with Fellini water, particularly the sea, creates transformations. Ivan wets his burning brow with water from a fountain, where two prostitutes comfort him (the blond is Giuletta Masina), restoring a smidgen of his masculinity. Women cause trouble, but cure it. Wanda’s suicide attempt becomes a parody death-and-rebirth, bringing her back to her bourgeois fate. The shoot by the sea reveals the White Sheik for the hen-pecked husband he is. And it is by the sea that Wanda learns the hard way how silly her dreams are, how she will have to conform herself to the constricted world of her husband and her relatives. No White Sheik for her!

As for us, if Fellini has a message it is to show the folly of setting up some imperfect mortal (like the White Sheik, and he is more imperfect than most) as an idol to be adored. That leads to a key question, Who is the real white sheik in this film? Who wears white robes all the time? Who is to be adored by the bourgeoisie trouping into St. Peter’s? As Philip Kemp has written, “If the circus seems to be his religion, religion is lampooned as a circus.” Or a fotoromanzo. One said such things softly in Catholic Italy of 1952, but say them Fellini did, and I at least can enjoy his satire, even in the age of Francis.

This was the first movie Fellini directed all by himself. But already he had assembled a team of people who could put his ideas onto film: the writers Tullio Pinelli and Ennio Flaiano, circus-y composer Nino Rota, cinematographer Otello Martelli, and above all his actress wife, Giulietta Masina. Reviewers didn’t like The White Sheik because it didn’t live up to their neorealismo expectations. This was no Rome, Open City (Rossellini, 1945) or Paisan (Rossellini, 1946), on both of which Fellini had worked. The reviewers expected him to continue in the same vein. But with this film Fellini began creating his own aesthetic, his worlds of strange-looking (or very beautiful) people behaving weirdly. Really his own world of cartoons and circuses—-and masterpieces.