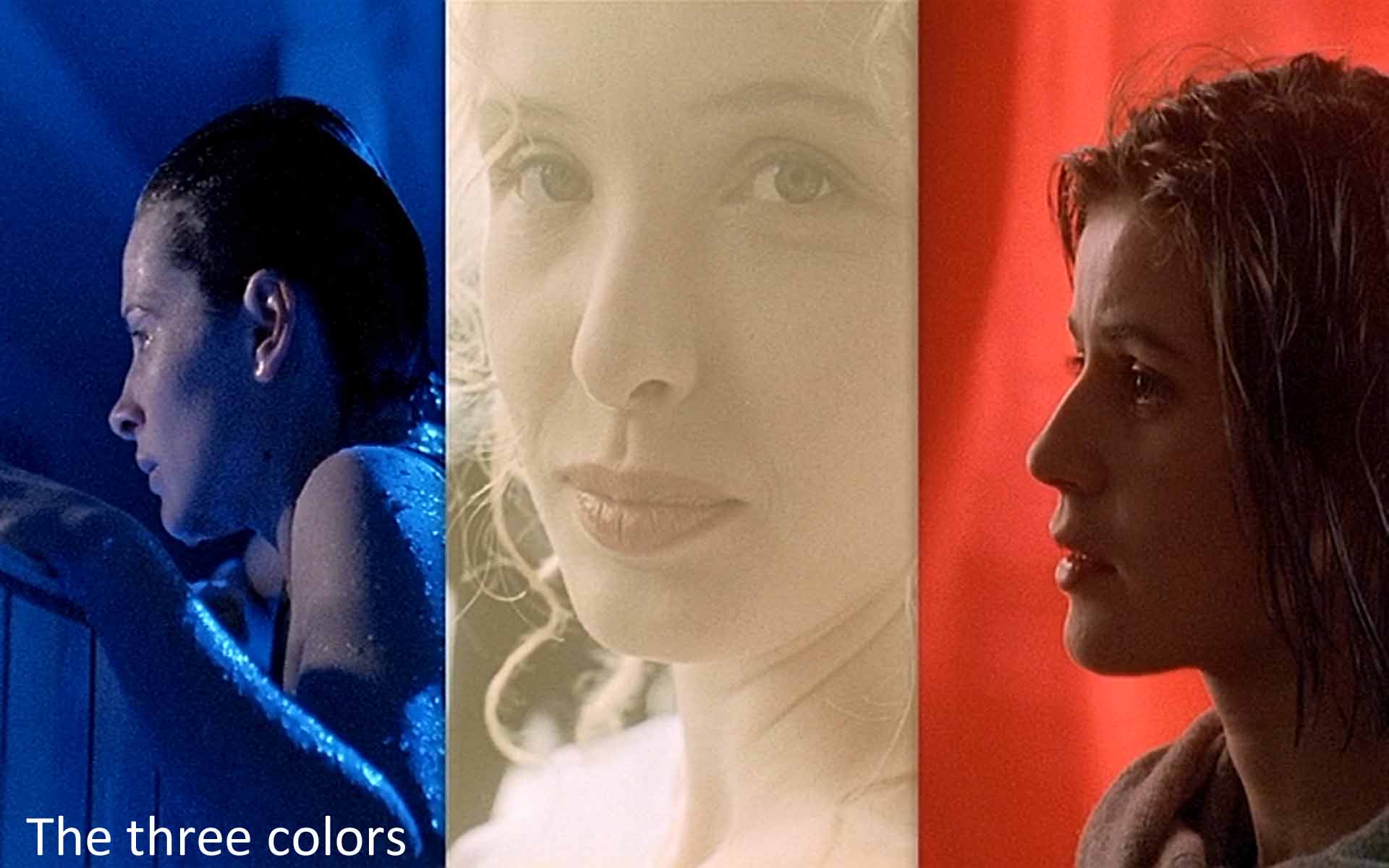

Trois Couleurs: Rouge rounds out Kieślowski’s magnificent trilogy. Bleu: liberté. Blanc: egalité. Rouge: fraternité. The main characters from the two earlier films come together in the last scene of this, the last of the three (although that scene was the first one Kieślowski filmed when he began making the trilogy). The last scene hints at the future lives of all six of these characters, and it briskly settles the inconclusive ending of Trois Couleurs: Blanc.

Red is very much part of the trilogy. In Red as in the other two, sexual betrayal is key to the plot. And Red’s final sequence leaves, like the other two, the leading character in tears. As the others do, Rouge opens with technology, the underside of our visible society, a poor substitute for the quasi-supernatural web of connections that Kieślowski posits behind our visible world. In Blanc, it was a baggage carousel, in Bleu, the hydraulics under a car. Here it is telephone wires.

In this, as in the other films of the trilogy, Kieślowski portrays the revolutionary ideal as contrary to human nature. Instead of brotherhood in the conventional sense, Kieślowski gives us a half-visible connectedness. Repeatedly he shows characters above or below each other. Paths cross and the principal characters who will ultimately be in love walk unknowingly past each other. One is Valentine, a young model and student in Geneva (beautifully played by Irène Jacob). The other is Auguste (Jean-Pierre Lorit), a young man studying to become a judge. (You become a judge in Switzerland by passing an exam.)

These unwitting connections give Rouge even more echoes and rhymes than the two earlier films of the trilogy, making it the most intricate of the three. Ultimately, I think, Kieślowski is suggesting, as with the other films, that revolutionary ideals like fraternité don’t work with human beings. Instead we have these strange behind-the-scenes connections, an invisible web within the visible world.

We have either that kind of connection or we can have a loving bond that may or may not include sexual love. The film gives two examples: the love an older man might feel for a woman who could be his daughter or granddaughter and oddly, the unconditional love we feel for our pets (here two dogs and one newborn puppy).

In the last moments of the film, the harsh, punitive judge at its center (Jean-Louis Trintignant) hugs that puppy. He is the most ambiguous character of the trilogy. Valentine finds out that he has been listening to all the telephones in his neighborhood, finding out his neighbors’ secrets, and cynically commenting on them. He admits his action is both illegal and immoral, and it incurs the wrath of his neighbors and a lawsuit. In appreciating this film, much depends on how you read him.

Several critics have compared this all-knowing judge to God, who is also a judge. In Kieślowski’s secular world, he is retired, a deus absconditus. He calls Valentine’s attention to how beautiful the light is, and the light lightens at his command. Later, when he has given up his godlike listening powers, he changes a light bulb. Fiat lux. HIs coin toss foretells or even controls Auguste’s coin toss. When the dog Rita tries to get back to the judge, she looks in a church. He seems to know Valentine’s and Auguste’s futures, and he predicts hell for the neighbors whose secrets he knows. Apparently he causes a meeting between Valentine and Auguste and at the same time punishes Auguste’s unfaithful lover, Karin ( Frédérique Feder). (Granted, he kills 1430 people in the process or 1360--the newspaper and tv counts differ. But then the Old Testament God was pretty casual about killing people who got in the way of his projects.)

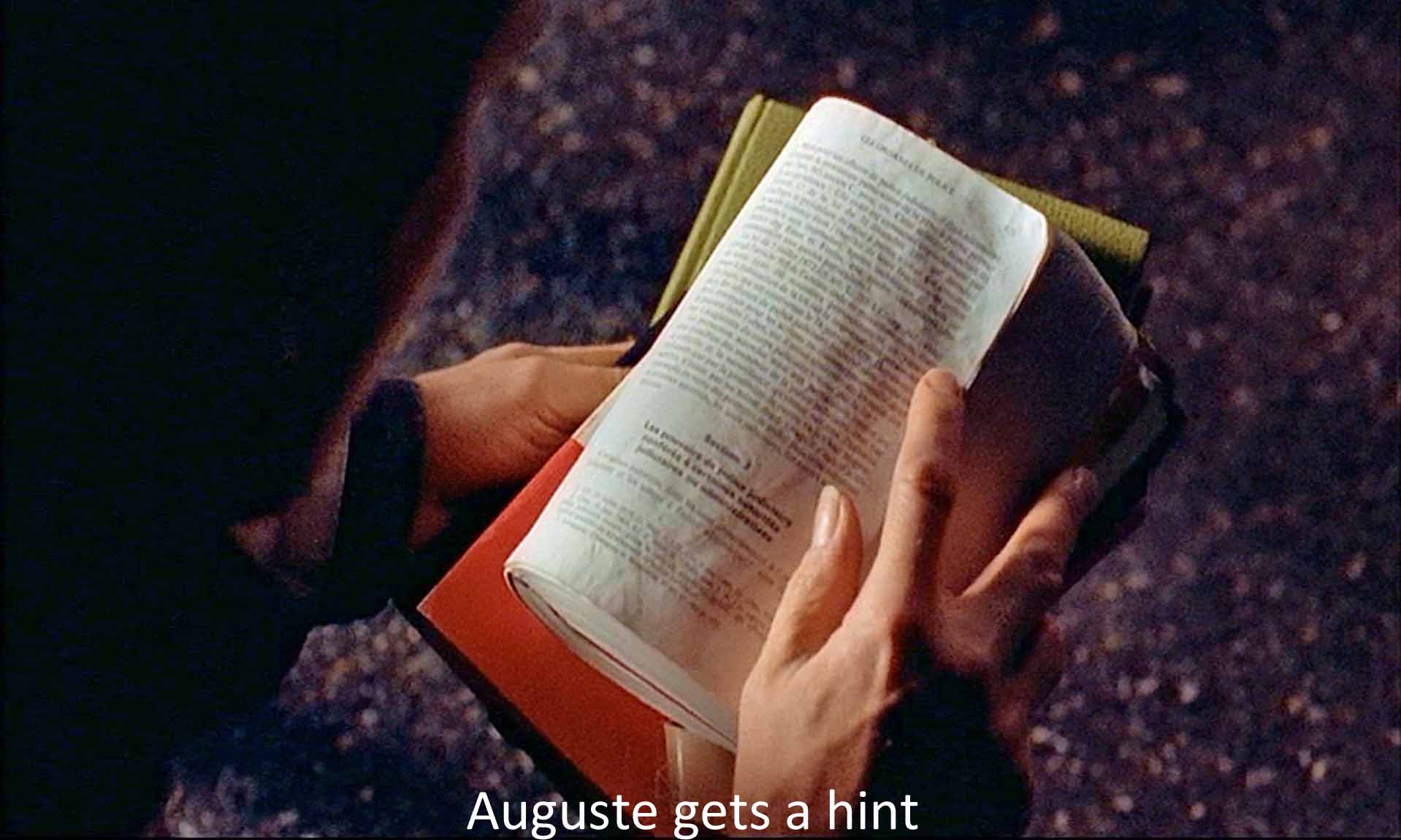

Kieślowski creates a series of parallels between the old judge, retired, and the young judge just starting out. For both, a law book accidentally fell open to the topic their examiners quizzed them on the next day. Both have fountain pens: Auguste’s is yet to work, while the old judge’s no longer works. Both were betrayed by blonde women they loved, and both were broken up by it. Both followed the woman and her new lover to England. It is as though the young judge is repeating the life of the old judge, and the old judge is now making it come out differently. The bitter old man says that he would have been better if he had met Valentine when he was young, and now he apparently causes a meeting between Valentine and the young judge as if to correct the earlier failure. Kieślowski himself has said that "the essential question the film asked is: is it possible to repair a mistake which was committed somewhere high above?" Is it possible to think of Auguste as the New Testament Christ correcting the harsh judgment, the “mistake,” of Old Testament Yahweh? With Kieślowski, I think, yes, such connections are possible.

Kieślowski also makes this judge do what a film director, another kind of god, does. He controls lights and characters. Kieślowski himself likened the judge to “a director.” “For me he resembles a chess-player who foresees the movements of the game. . . . “ (Amiel 146, quoted Insdorf 178). Kieślowski’s cinematographer Piotr Sobocinski describes Kieślowski’s method: “Instead of omens forewarning of some future happening, we designed later scenes to show that some earlier, apparently casual events, were important to the story.” Kieslowski said in a "master class" on the DVD: “In Red, particularly, we wanted the viewer to think backwards, to make associations with things he had already seen without noticing." "But we tried to build up these signs, particularly in Red, so the viewer would realize that what he sees here, he has already seen, and would register that in some part of his subconscious. Many of the signs will not get through to him, but we let them build up so that at least some do, so that he understands the principle.”

It is this "principle" that governs Kieślowski’s world-picture and his style of filmmaking. For example, he hired the expensive Technocrane, new in Europe at the time. With it, he could make such remarkable shots as the camera following the trajectory of a book falling from the balcony of a theater to the pit or the shot in which the camera travels from Auguste leading his dog out of his apartment building, across the street, and up into Valentine’s window where she answers her phone. The device gives his "principle" of connection visual form.

The judge also resembles Prospero in The Tempest, an old magician who can foretell the future for his characters, who can perhaps create a storm, who has rejected the world, who is redeemed by a young woman. And many critics have pointed out how close “the judge” is to Kieślowski himself as he contemplated retirement, very like Shakespeare and Prospero, for whom “every third thought shall be my grave.”

At any rate, he is something more than simply “a retired judge.” His name “Kern” means seed in German, and he comes to life again through Valentine. Irène Jacob says (in her DVD interview) that she picked the name on a whim. Nevertheless, Kieślowski liked it and accepted it. Valentine is the saint of love--and so is this young woman. She plays an angel of mercy to this harsh, perhaps supernatural judge. And one can read this film in yet another way, as showing how mercy counters a hard, punishing judge. As Shakespeare’s Portia says, "[E]arthly power doth then show likest God’s / When mercy seasons justice." And, as for loving the puppy (somewhat undignified for a deity), an animal rescue site I know has the motto: “To our pets, we are God." By the end of the film, the judge has been redeemed, changed from a man with nothing but angry contempt for his neighbors to someone who empathizes with them, someone who can love.

I’m rather surprised that no critics (so far as I can tell) have asked how the judge manages to listen to his neighbors’ landline phones. In Rouge’s dazzling opening sequence, Kieślowski reminds us of the complicated wires by which these 1994 phones are connected. To listen to his neighbors’ conversations, the judge would have to have wire connections to each of their telephones. But the film seems to show him listening wirelessly. To be sure, some have cordless phones, and the judge could be listening to the signal between base and handset. But that’s a weak signal, and these phones are far away. Valentine heard his system on her car radio, and a shot of a government radio truck confirms the wireless idea. But, frankly, I don’t think such a wireless eavesdropping is possible. To me, this engineering impossibility adds to Kieślowski’s hints that the judge is some kind of supernatural figure, presiding over a world of connections, wired and otherwise.

This film about relationships is thick with rhymes and echoes and visible and invisible connections:

Red The color dominates the palette and the connections of Red. Red we can associate with all kinds of human interactions: blood, desire, shame, anger, love. It would be impossible to list all the reds in Red: from the huge poster of Valentine advertising chewing gum to the tiny cherries on her yogurt cup (that echo the cherries in the slot machine she plays at Café Joseph that echoes the judge’s name, Joseph, and so on and on). Cinematographer Sobocinski seems never to have lost a chance to put in some red.

Telephones Kieślowski could have called this film "Telephones" instead of Red. The film teems with telephones, starting with the opening sequence tracing the telephone wires from England to Geneva. Valentine’s boyfriend in England telephones her, Auguste telephones his girlfriend who runs a telephone weather service, and the most important telephoning is the judge’s listening to his neighbors’ telephone conversations. Everybody telephones everybody with the intriguing exception of Valentine and the judge: they never telephone each other.

Glass In this as in the other two films, windows and glass both separate people and reveal them to one another. Here, a broken glass in the bowling alley tells us that Auguste was there and that he was angry. The outraged neighbors throw rocks through the judge’s windows to signify their rage. In their last conversation, Valentine and the judge press their hands on either side of the glass of his car window: intimacy and affection, but, ultimately, separation too.

Levels. Kieślowski often shows us characters on different levels, one above or below the other. When Valentine and the judge talk in his house, one is always higher than the other. In the crucial final conversation between Valentine and the judge, she stands on the stage looking down at him. When Karin looks for Auguste, he hides on a walkway beneath her. I think Kieślowski is suggesting that true equality, fraternité, doesn’t happen.

The recycle bin An old person trying to put a bottle in a green recycle bin appears in this film as in the other two, but differently toned. In Blue, Julie, totally self-centered, “free,” doesn’t see her. In White, Karol Karol sneers: he’s just as bad off as I am. But in Red, the angelic Valentine helps the old lady out.

Then there are small, obscure connections. The poster of a dancer on a wall in Auguste’s apartment shows the pose Valentine will assume later in her dance class. The judge’s name is Joseph; Valentine lives above the Café Joseph. Both the veterinarian and Valentine’s brother are named Marc. Both Auguste and the judge saw their lovers in flagrante delicto. Auguste, distraught, lets the battery in his car run down. Later, the judge says that he had to recharge his battery to come to Valentine’s fashion show. Valentine appears in a huge poster advertising gum. Then, when she comes back to her apartment, she finds someone has stuck gum in the lock. Bubble gum is “a breath of life,” and the huge poster is echoed in the television shot of Valentine after she has survived the ferry disaster: she will live and live, we can guess, with Auguste.

In the opening conversation between Valentine and her lover in England, he tells her he went to see the movie, Dead Poets Society (Weir, 1989). Why this particular movie? Because it too uses red symbolically. A subdued red is the school color of the uptight prep school the film condemns. A stronger red serves as the color for its neighbor, a far more violent and passionate public school. “Getting red,” says one of the boys, “means giving yourself virility; it will drive girls crazy.” Red in Rouge is also the color of passion, but more subdued, and in a far stronger movie.

In a key conversation the judge tells Valentine that he should have met her years ago, then he would have loved. A janitor comes by and asks them if they have seen a woman “avec des seaux,” with buckets. What is this bit doing there? “Des seaux” as the janitor pronounces it echoes “Dusseau,” Valentine’s last name. The judge, like the janitor, is looking for a “dusseau” in order to help her.

One particular source of critical angst is the seventh survivor, "Steven KilIian, English citizen, barman on the ferry." We’ve heard nothing of him before, but he occupies this key position in the film. Why? True, he makes the canonical seven (seven puppies or the seven baby rats in White). I suggest, though, that Mr. Killian refers to Killian’s Red, a well-known biere rousse, and this is one penultimate hidden version of “red.” This survivor is, after all, a barman.

There are doubtless many more such nuances and details awaiting the assiduous critic. Kieślowski is endlessly ingenious.

With Mr. Killian and the six other survivors, the trilogy comes to an end, an overwhelming demonstration of Kieślowski’s world-view, that there are hidden connections within and beyond the world we sense, that the world is pregnant with relationships if we could only see them. In these three films, he brilliantly makes visible just that, a world of interconnected humans. In doing so, he has created three masterpieces that set him in the top rank of filmmakers, despite his tragically short feature film career. As for Rouge, I think it is the most intricate and profound film I have ever seen.