For a movie set in 11th-12th century Japan in a gloomy rainstorm and with an even gloomier theme, this movie has traveled far. Homer Simpson refers to it and Archie Bunker as well as the high-highbrow philosopher Martin Heidegger. It has spawned a host of imitations: Last Year at Marienbad, The Usual Suspects, Oliver Stone’s JFK, to name a few, and of course there was a Hollywood remake, The Outrage (Ritt, 1964). Sociologists and criminal lawyers have taken to speaking of “the Rashomon effect.” After the 2016 election in the U.S., we can recognize this as a “post-truth” movie, full of “alternative facts.”

The scene: 11th or 12th century Japan, a time of fire, earthquake, pestilence, banditry, war, all the four horsemen. The movie opens with an overpowering rainstorm at the Rashomon Gate, the main gate to the city of Kyoto. The gate is in ruins, and we are told that the city is as well.

The gate makes a powerful symbol. It is both inside and outside the city. Inside is what is supposedly safe and civilized. Outside is the forest, a place (traditionally) of gods and demons, but also, we are told, where “men lose their way.” The gate reminds us of civilization, but it is in a state of ruin. A gate also symbolizes a beginning or an end—think of January and Janus, the double-faced god of gates. Think too of a gate as a symbol for birth, in both an anatomical and a metaphorical sense. And death. This film begins with death and ends with a baby, all at this gate. No wonder this gate was the one hugely expensive item Kurosawa insisted on in his budget. No wonder Kurosawa named his movie for the gate.

Under this ruined Rashomon gate, a woodcutter and a priest have taken shelter from a torrential downpour. They first puzzle, then lament the “queerest” event at the Police Court three days previously. They seem devastated by what they have witnessed. Worse than earthquakes, plagues, and wars, they say.

A third man joins them, a “commoner,” a thoroughly cynical and disillusioned man from the city. He indifferently breaks off pieces of the gate and burns them. (Yet this is practical! It keeps all three warmer.) For him, the gate corresponds to the disillusionment, the failure of human institutions, which the priest, woodcutter, and commoner lament. This city-dweller, however, eager to hear a yarn, keeps questioning until the priest and woodcutter tell their stories. They are horrified by what they have seen, but the city-dweller—and I write as a New Yorker—knows all too well the ways of human beings, particularly when it comes to telling the truth. The commoner bitterly comments on them throughout the movie. When the naively hopeful priest says, “If men don’t trust each other, this earth might as well be hell,” this man replies, “Right. The world’s a kind of hell.” “You just can’t live unless you’re what you call selfish.” “I even heard that the demon living here in Rashômon fled in fear of the ferocity of man.” “Man just wants to forget the bad stuff, and believe in the made-up good stuff. It’s easier that way.” “I don’t mind a lie if it’s interesting.” (This guy has a future as a critic!)

Once the city-dweller has persuaded the priest and the woodcutter to tell their stories, the scene shifts for the telling. The gate is the place of suffering. The forest is the place of uncertainty. Flickering sunlight and abundant foliage obscure the view. Now, in clear, flat lighting, the police court is the place where we are supposed to find out truth. Supposed.

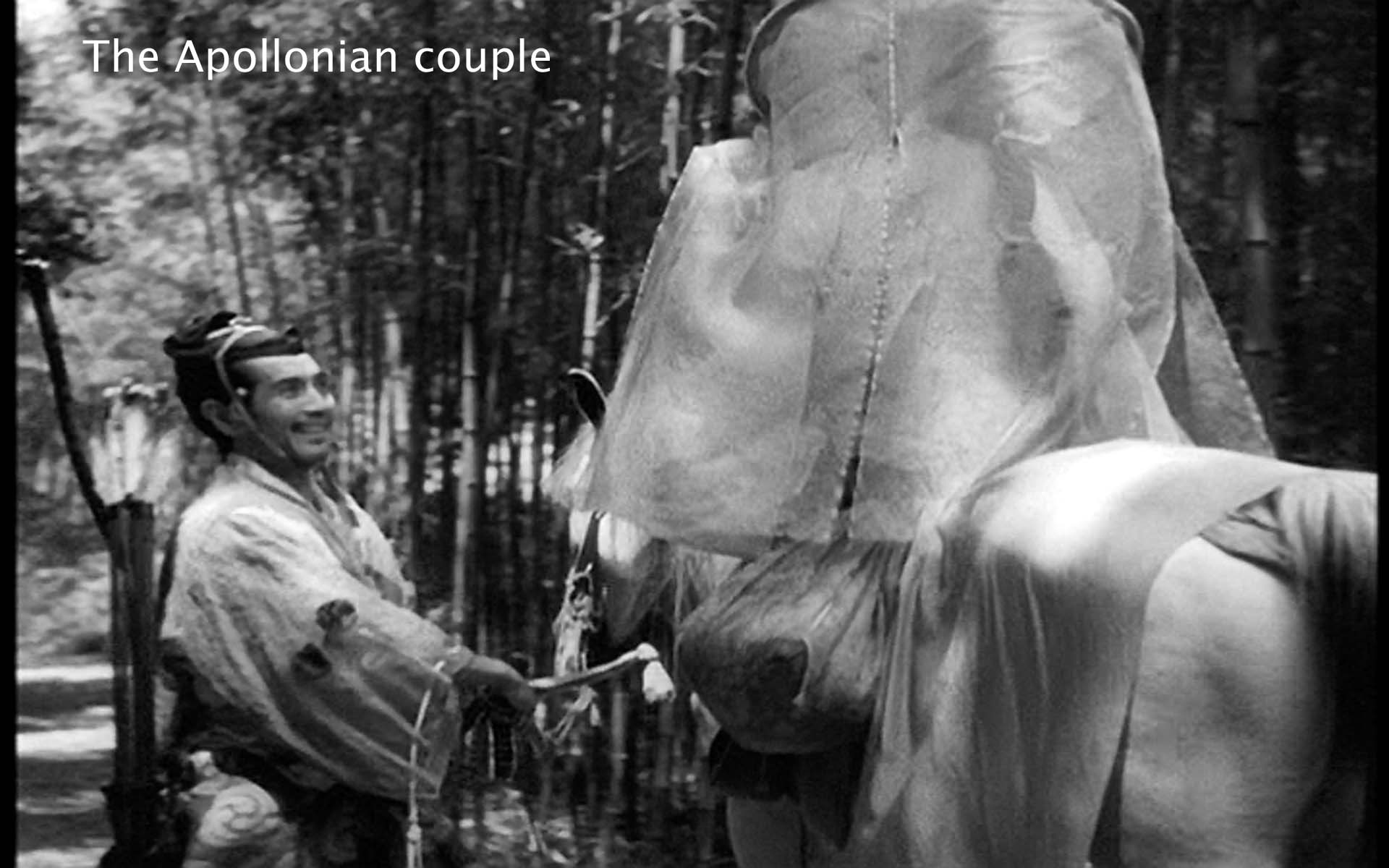

At the police court, the woodcutter testifies how, in the forest, he came upon a woman’s hat, a man’s pocketbook, some rope, and then the man’s body. (Takashi Shimura, who plays the woodcutter, starred in another Kurosawa masterpiece, Ikiru.) The priest testifies how he had met, in the forest, a man leading a horse with a veiled woman on it. In the police court, people hold static postures. When the film shifts to the forest, people stumble and fall.

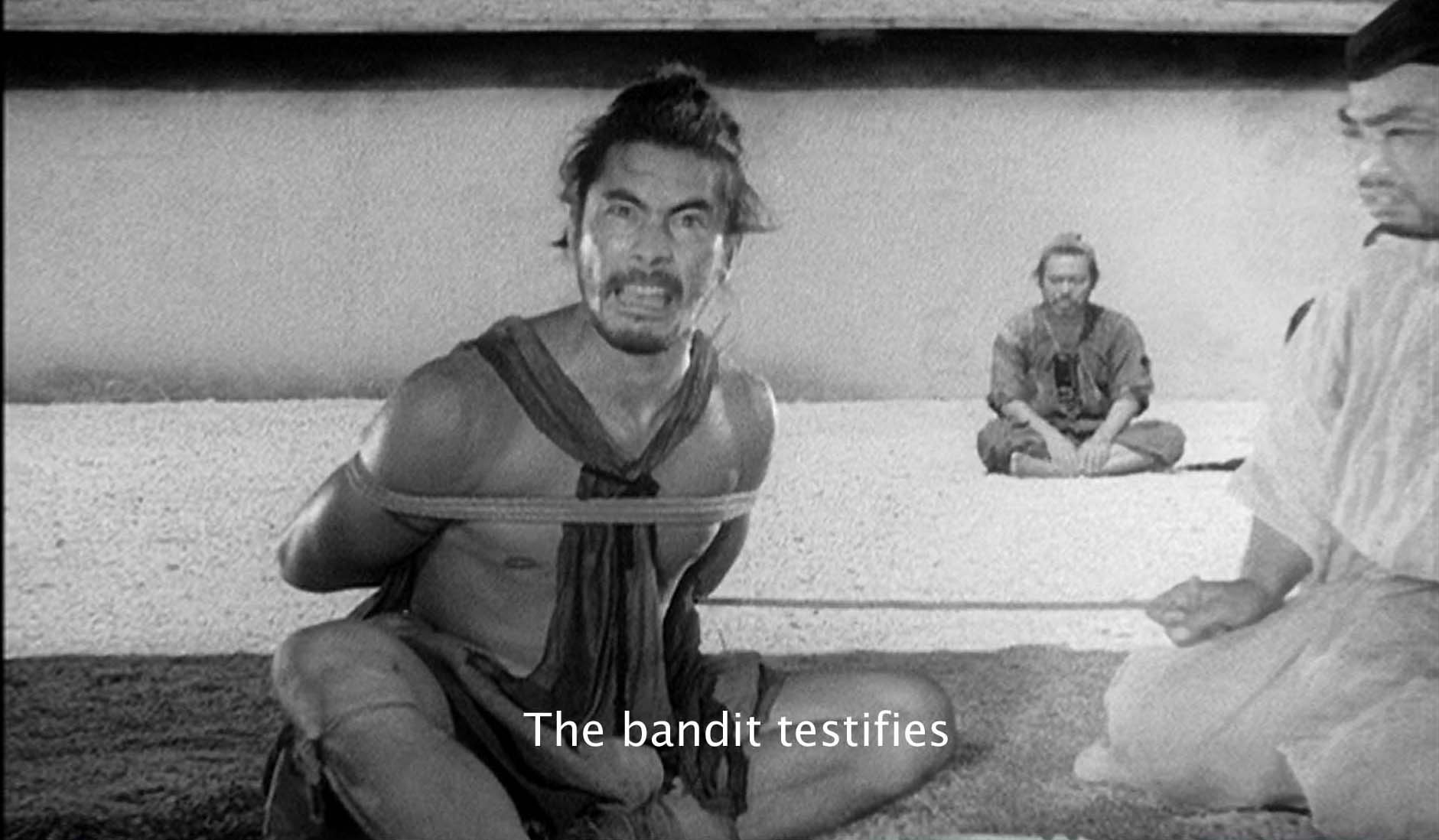

For the murder, the police arrested a well-known bandit, Tajomaru (played by Kurosawa’s great actor, Toshiro Mifune). The bestial bandit contrasts with the cool, aristocratic man. The bandit reminds us of a class structure, also broken down in the forest. His sword, rising against his leg, suggests his lustful thoughts. Here, as often in his other roles, Mifune seems almost animal-like, and indeed Kurosawa sent him to the zoo to learn from the monkeys. His constant scratching, his fleas, and his leaping about link him to animality. His crazy laugh, his mention of his drunkenness, and his murderous violence link him to the irrational. In Western terms, I can read him as a Dionysian contrast to the aristocrats who start out serene, graceful, and harmonious, if you will, Apollonian.

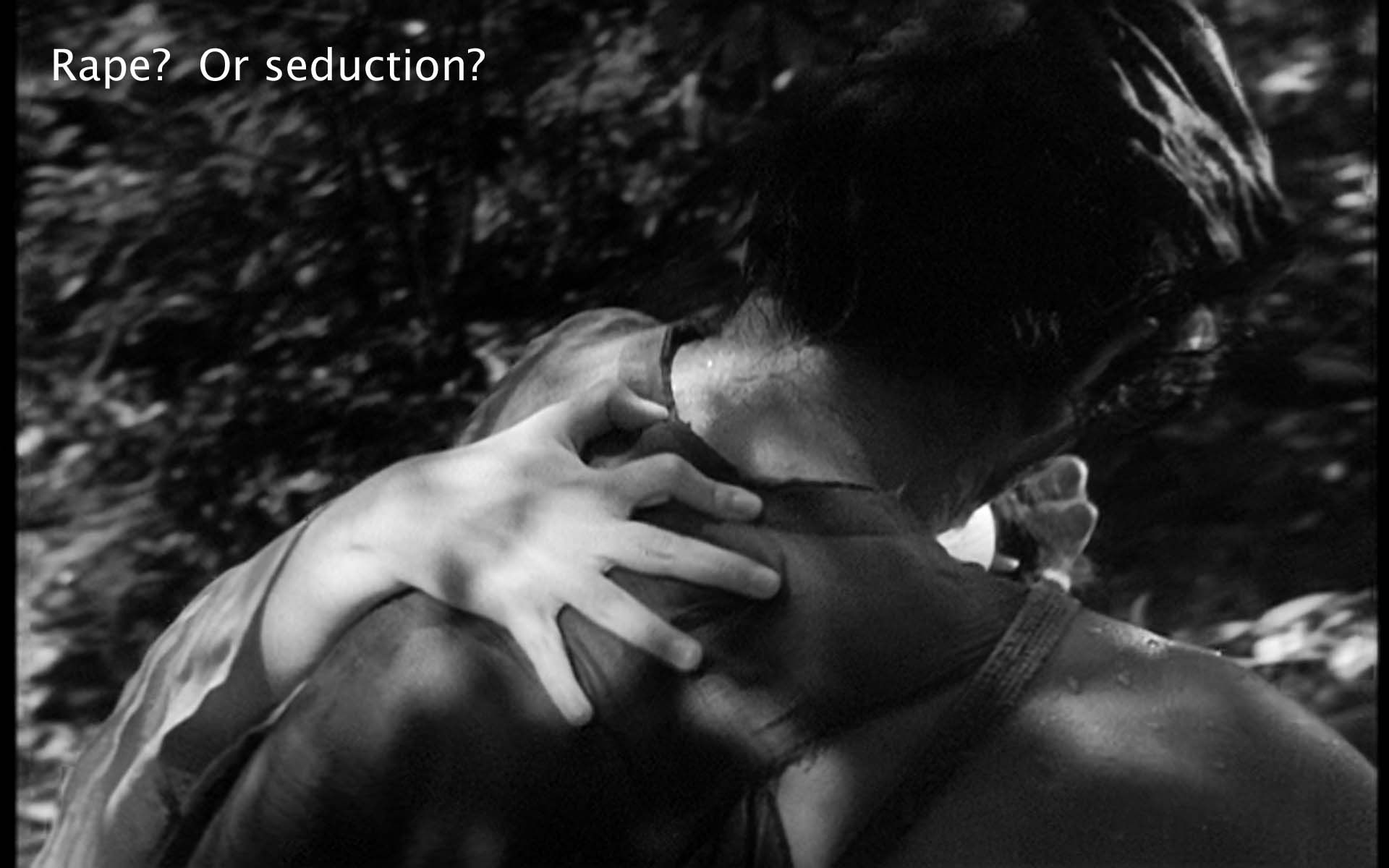

The bandit testifies how he met the man and woman. He lured the man to a supposed cache of swords, jumped him, and tied him up. He then led the woman to that spot, overpowered her, and raped or seduced her before her husband’s very eyes. Then she, taken with him, insisted that he kill her husband. Instead, he released the man and gave him a sword, so they could settle to whom the woman would belong. They fought (“I still admire his swordsmanship”) until he killed the husband. He took the horse, sword, and arrows and fled.

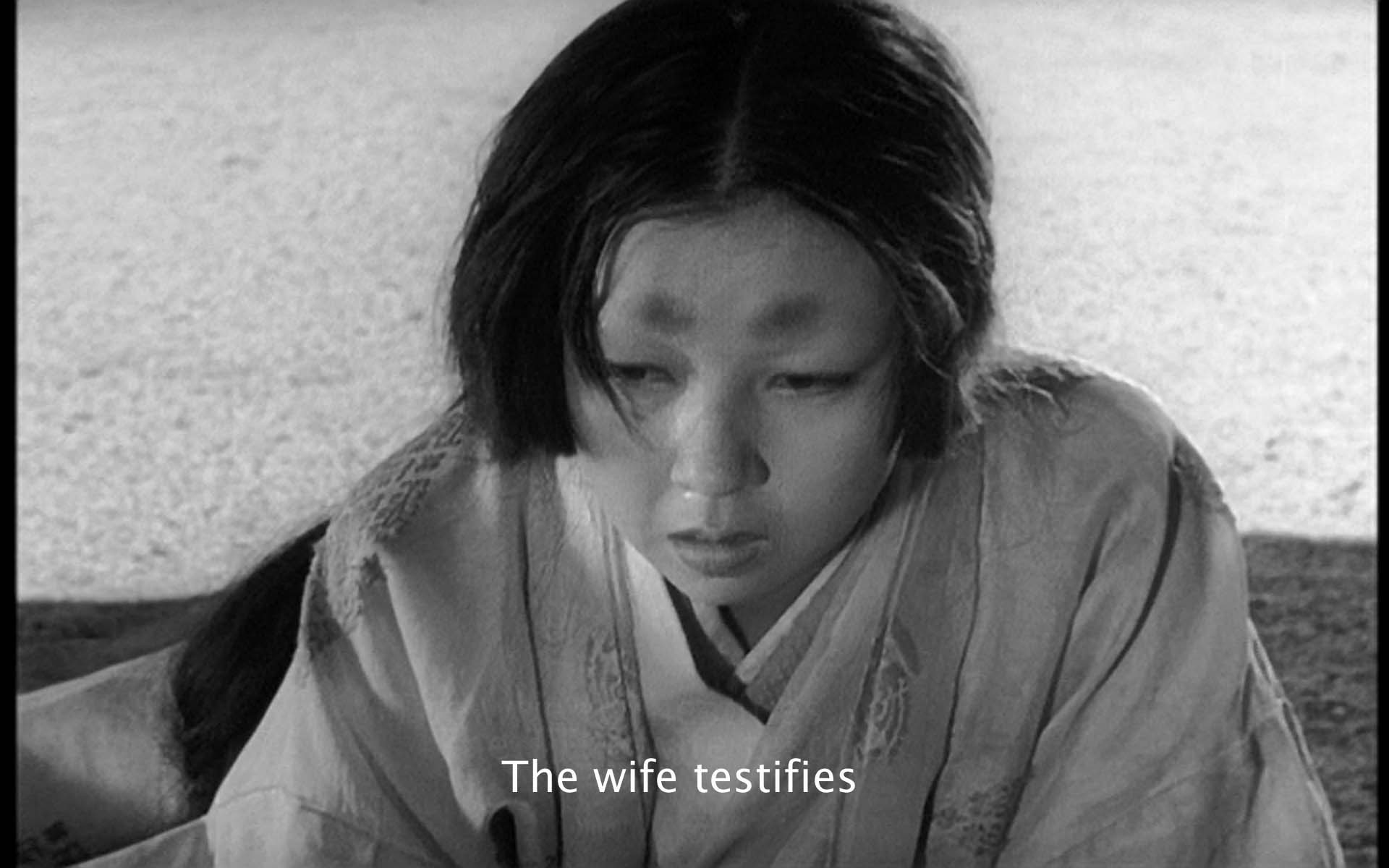

The priest then tells how the wife, in her turn, testified that, after the rape, the bandit left her to face her husband. He looked at her with such scorn that she collapsed. On waking, she found her dagger in her husband’s chest. She tried to commit suicide herself, but could not. “What should a poor woman do?” Shamed and outcast, she has immured herself in a convent.

The next witness is a medium who goes into a trance and purports to speak for the husband. He then tells through the medium, how, after the rape, the wife, radiant with love, tried to attach herself to the bandit. The bandit, however, disgusted, released the husband who committed honorable suicide with his wife’s dagger. As he is dying, we see a hand taking the dagger out.

Back at the gate, the woodcutter proclaims that all these accounts are lies. He now tells us that he not only found the body, he witnessed the whole thing. After the rape, the bandit begged the woman’s forgiveness and offered to marry her. She goaded the two men into fighting. They stumbled and fell and shook with fright in a clumsy slapstick duel, but finally the bandit killed the husband.

Just about everyone who comments on this film takes the five different tellings of the murder and rape to be the central theme. This is the “Rashomon effect.” Surely these contrasted versions form the central theme of the film. But it is important to remember that these perspectives are not just different, they are nested. We in the audience are two steps removed from the rape and killing. Kurosawa makes this clear by sharply distinguishing the police courtyard from the ruined gate or the deceptive forest.

The police courtyard has a neatly raked gravel garden against a plain wall, with a roofline cutting horizontally across the film frame. Everything is neat, orderly, planned—quite right for a court and very different from the dilapidated gate or the confusing forest. The witnesses speak directly to us, looking right out of the frame. The first witnesses, the woodcutter and the priest, watch the later witnesses give their accounts, while we play the judges. But, again, it is important to remember that the samurai, his wife, and the bandit are not “really” speaking to us. This is flashback. We are hearing only what the woodcutter and priest tell us.

In a move that anticipates the central event of the film, the three narratives, the policeman who arrested Tajomaru says he thinks the bandit was thrown from the horse that he had stolen. Tajomaru indignantly replies, in a flashback, that he had drunk bad water and was lying by the riverbank agonized with cramps. Two witnesses—two versions, and each version answers to the witness’s need. Tajomaru needs to defend his masculine prowess; he doesn’t fall off horses! The policeman needs to see this powerful, frightening bandit reduced to size. The flashback takes us from the straight lines of the court to the relatively straight lines of the riverbank to the tangled, sprawling forest, a place where “men lose their way.”

That, of course, is where the central events of the film take place, the leafy, jumbled forest and the flickering, dappled light that Kurosawa created in the forest of Nara. In the court, Kurosawa uses wipes to move from scene to scene, as if to build that orderliness into his transitions. By contrast, in the forest the camera jumps from point of view to point of view, up, down, at several points shooting into the sun itself, a radical innovation by the director and his brilliant cinematographer, Kazuo Miyagawa.

In the forest, camera conventions say, we are seeing what “really” happened, but we aren’t. We are seeing what the bandit, wife, husband, and woodcutter tell us happened. As the legendary director Robert Altman says in his commentary on the DVD, “It is all true and none of it is true.”

As all the analysts of this film point out, we only learn the central events through the eyes of the witnesses, and they each give a version that fits the needs of his or her personality. The bandit wants to seem fiercely, wildly, macho. His story plays up his manliness as lover and swordsman. His story is sensual (as he responds to the breeze that lifts the lady’s veil). He sweats. He swats gnats. He is tough! I am intensely aware, during his version, of his skin, of her cheek, of the stream nearby, in general, of surfaces.

The wife penetrates to a psychological level, addressing her own and her husband’s feelings. The story she tells plays her up as a poor, helpless, suffering woman.

The husband wants to seem noble and proud, even under these degrading circumstances. He tells a tragic story in which he, with painful resignation, always does the honorable thing expected of a samurai.

As for the woodcutter, it is important to remember that he is the only proven liar among the witnesses. Near the end of the picture, he virtually admits stealing the dagger. He tells us at the gate that he saw the whole thing, although earlier he told the police he only found the body. He accuses the others, however, of telling “Lies! All lies!” In his version, he breaks down class differences. He makes the “high” people, the noble couple, and the famous bandit, seem as low as himself. If the others’ tales are sensual, psychological, and tragic, his is farcical.

It is hard to be sure, but each of these three people seems to believe what he or she is saying, all except the woodcutter who will later admit that he was lying. As the city-dweller says, “[Humans] can’t tell the truth even to themselves.” And the priest says, ”Because men are weak, they lie to deceive themselves.” Kurosawa has put into their mouths the idea informing this film as he stated it in Something Like an Autobiography:

Human beings are unable to be honest with themselves about themselves. They cannot talk about themselves without embellishing. This script portrays such human beings—the kind who cannot survive without lies to make them feel they are better people than they really are. It even shows this sinful need for flattering falsehood going beyond the grave—even the character who dies cannot give up his lies when he speaks to the living through a medium. Egoism is a sin the human being carries with him from birth. It is the most difficult to redeem. This film is like a strange picture scroll that is unrolled and displayed by the ego.”

In other words, each character is telling what seems to them true, because they need it to be true.

One critic (Gerald Mast in his A Short History of the Movies) notes that Kurosawa has adapted his camera work to the different narratives. He tells the bandit’s story with furious tracking and panning shots, an extremely mobile camera that matches the bandit’s impetuous, irrational nature. He builds the wife’s story from cross-cut close-ups, exploring the characters’ states of mind. For the husband’s story, he uses a high camera, relatively fixed, with long takes, to get an effect of seriousness, stateliness, solemnity. In the woodcutter’s version he keeps the camera at a goodly distance from the characters, thereby showing them as smaller than in the other versions. In effect, Kurosawa, like the witnesses and the participants creates his own versions of the three stories.

Notice, too that we are not even seeing these witnesses tell us their stories in the court, although the occasional cuts to the police courtyard would normally suggest that. Kurosawa has created yet another level of deception. Like the listener at the gate, we are only “seeing” what the priest and the woodcutter tell us.

The different narrations in the police courtyard teach us a universal truth: people see and know and understand events out of their own individual needs. That truth applies to the priest and the woodcutter as much as to the husband, wife, and bandit. What then are the individualities and needs of the two witnesses who form the frame or gate of the film? (Indeed, what about the needs of the entranced medium?)

Most strikingly, the three central figures can gain nothing by their lies. The bandit says he will hide nothing since he is going to hang anyway. The wife has fled to a nunnery. Her life in the world is finished. The husband is dead. But they distort out of sheer human need which is more powerful than any moral or metaphysical truth. I think that in the opening and closing statements of bafflement and disillusion we are hearing the priest’s and the woodcutter’s naivete.

One can read the woodcutter and priest as defining secular and religious types. The woodcutter tells us the men’s stories (his own, the bandit’s, the husband’s). The priest tells us the wife’s story. I notice that the priest saw the husband alive. The woodcutter sees him only dead (in his first account, anyway). The priest (so far as we see) tells the truth. The woodcutter, however, lies, and he distrusts and disbelieves the stories of the others (”Lies! All lies”), despite his own lying (or because of it). The priest wants to trust, wants to believe, wants to sympathize. He is rather a naive figure. His first puzzlement takes the form of announcing that even a learned abbot (whom he names) would not believe what they have seen (the difference in the three accounts). Does that seem likely? Would not the learned abbot (if not this naive priest) understand the subjectivity of people’s perceptions and accept it without losing his faith in human nature?

For me, a New Yorker, the big puzzle in this movie is, Why do the priest and the woodcutter think this is so horrible? Worse, says the priest, than earthquakes, plagues, or wars. Worse than people being killed by the hundreds. Why? For anyone reading the headlines in the twenty-first century, this one rape (or is it seduction?) and this one duel (or was it suicide?) seem relatively mild.

Apparently, however, it is not the crime as such but the differing accounts of it that so distress both the secular and the religious man. “I can’t understand it,” says the woodcutter in the opening words of the film, “the queerest thing.” Yet to us in the twentieth-first century the idea that we sense and know things as functions of our own individualities has become a familiar teaching of psychology, a central tenet of postmodernism, and the core of my own theoretical position, reader-response criticism. I do not feel it has destroyed my faith in humanity. Rather I feel I understand myself and my fellow humans a bit better for that insight. Why is this such a shattering truth for the priest and the woodcutter?

In short, then, what is the focal point of Rashomon, the idea around which it takes shape as a work of art? I think that focal idea is: We humans see, know, witness, and understand out of our own individualities, but Rashomon applies that idea to every person involved in the film—including the primary witnesses, the priest and the woodcutter, and to Kurosawa and his camera, and to me, the film critic seeking fame and glory by writing this—and to you. If you like, this is a film about believing a film which is about not believing. Except, perhaps, for the person who made it, Akira Kurosawa, who must surely believe in his own art, and deservedly so.