René Clément’s Plein Soleil makes many changes from the Patricia Highsmith novel (The Talented Mr. Ripley) on which it is based, but the core plot remains the same. Playboy Philippe Greenleaf (Maurice Ronet, he of the cruel mouth) is enjoying life in Italy, traveling here and there, carousing at night, sailing his magnificent boat during the day, making love to his fiancée Marge (Marie Laforêt) and to others on the side. From America his rich industrialist father has sent over Tom Ripley (the stunningly handsome Alain Delon) to persuade his son to return to San Francisco and settle down. If Tom succeeds, he gets $5000 that he desperately craves. (Clément gives us several shots of him ravenously eating to signal his hunger.) Philippe enjoys Tom’s company, but he also abuses him. Philippe casually “forgets” to write his father that he is coming, the $5000 is withdrawn, and Tom is hurt and angry.

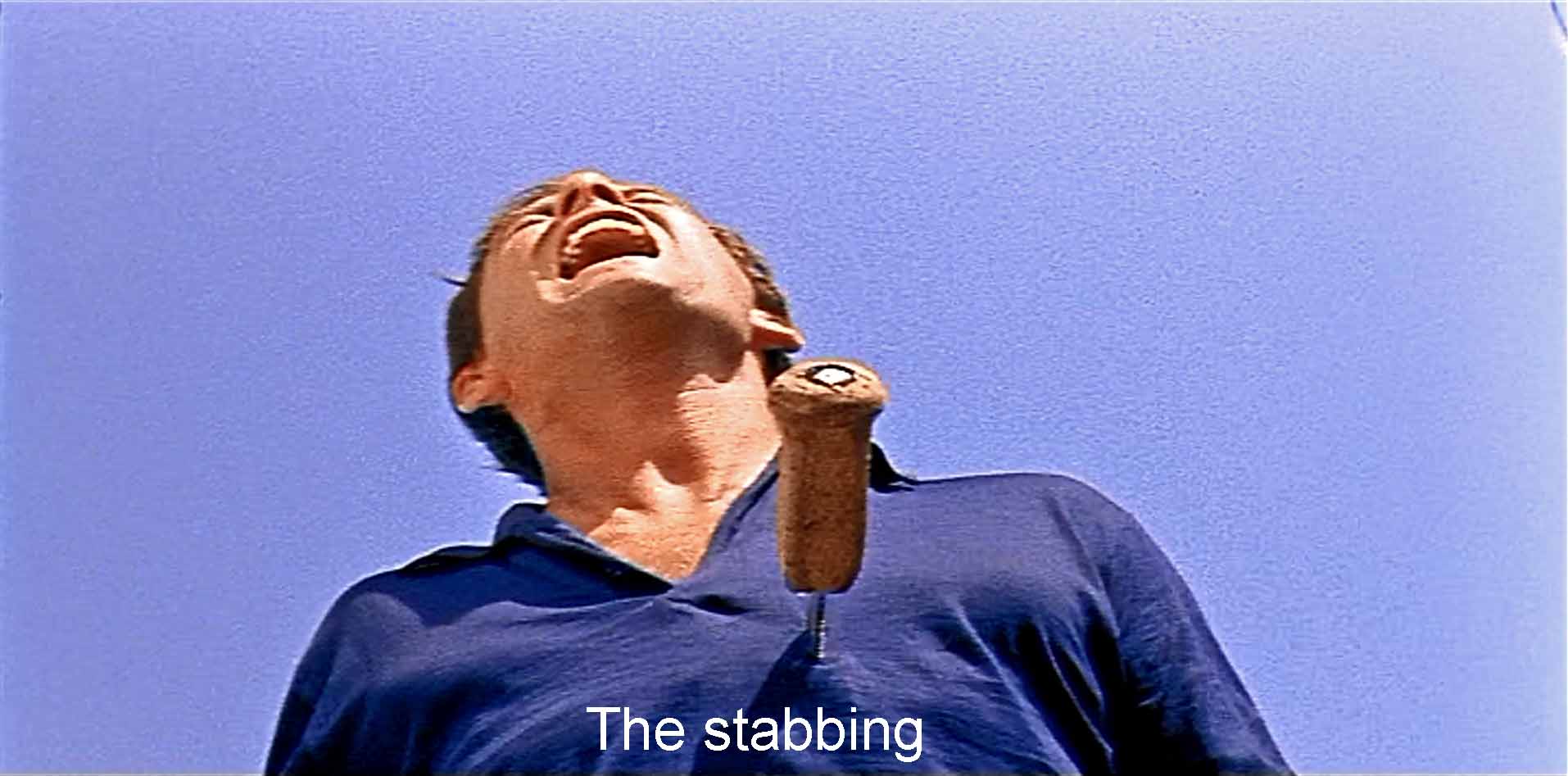

But he doesn’t give up; he hatches a plan. Having gotten alone with Philippe on the boat, Tom stabs him as they are discussing Tom’s plan to do just that. He drops the body in the sea and, returning to shore, creates a Philippe Greenleaf whom he becomes. In a dizzying series of plot twists he is Tom to some (Marge, Mr. Greenleaf, a cheap hotel) and Philippe to others: the bank, the boatyard, and a swanky hotel. Philippe’s snobbish friend Freddy smells a rat, and Tom disposes of him as well. He fakes Philippe’s suicide, and finally he possesses, as Tom, Marge and the money Philippe has left her. And then there is the ending.

Clément establishes his theme of fluid identity from the start. The very first thing we see is a seaplane, both boat and plane, navigating sea and air to take Tom and Philippe on a runaway weekend to Rome. Cut to Tom imitating Philippe’s signature on the postcards he is too lazy to send. Tom suggests placating Marge, who is writing a book on Fra Angelico (a monk who changed his identity), by buying her a book on the artist that she can sign and pretend is her work. Philippe’s friend Freddy Miles (Billy Kearns) appears, not knowing the names of the two women he has picked up.

Then comes the most startling episode of fluid identity. Philippe and Tom confront a blind beggar, buy his white cane from him, and march off pretending to be blind. The blind man gets into a cab from which emerges a blonde who joins Philippe and Tom in their playacting until they abandon her on the Via Veneto. Total fluidity. You can be who you want to be. Maybe.

These identities’ shifting take place on land. Later, after Philippe’s apparent disappearance mysterious characters appear, notably an eavesdropping woman in the restaurant scene. They are police spies with unexplained Identities. They form part of a pattern of the unexpected suddenly popping up, a foreshadowing of the ending. On land, many shots of priests and nuns remind us of Tom’s guilt as does a shot of innocent schoolgirls playing when he looks out the window after killing Freddy Miles. Things are complicated on land.

At sea things remain all too clear. Philippe frankly abuses Tom. He strands him in a dinghy tied astern while he makes love to Marge. The line holding the dinghy breaks, and Tom is left alone in the wide, wide sea to be cruelly sunburned. Philippe throws Marge’s manuscript overboard, showing what he thinks of it and her. Tom frankly describes his plot to murder Philippe. Once he does so, the boat veers crazily in the wind as Tom tries to master her, as if to rebuke him for the crime. Things are clear-cut at sea, and in the finale the truth will come up out of the sea.

That may explain a curious scene in which Tom and the camera pass leisurely through a fish market. We see all kinds of odd fishes that have come up out of the sea, culminating in a ray that smiles mockingly at our murderer. In the finale, the truth will come out of the sea. The ending is not, as some reviewers have suggested, simply a gesture toward conventional morality but a culmination that logically follows Clément’s contrast of land and sea.

Incidentally, the French title means “full sun,” or “bright sun,” referring I think to the clarity of things at sea. The strange English title, “Purple Noon,” comes from a poem by Shelley that contrasts the poet’s dark mood with the bright sea and sunshine. In the same way the film contrasts Tom’s dark scheme with the bright Mediterranean sea and sky marvelously photographed in gleaming Eastmancolor by cinematographer Henri Decaë. Out there things are clear; on land they shift and turn mysteriously.

Reviewers seem compelled to compare Clément’s 1960 version of Highsmith’s novel with Anthony Minghella’s 1999 version. But the two approached the adaptation quite differently. Minghella developed an idea of improvisation and worked jazz and classical music into the story in a highly inventive way. He was more inventive. Clément used the sun and sea that are intrinsic to the Mediterranean setting. So be it. Reviewers like to then proclaim one better than the other. I’m content to say they’re quite different and leave it up to you to decide which you prefer and why.