Don’t forget that the title of this movie has two parts: The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant plus a subtitle: A Case History. The first title tells us this is melodrama. It promises to pump up our emotions by showing women [usually] in desperate situations. This will be highly emotional, although Kant is as rational a philosopher as there is. The subtitle tells us this deals with psychopathology. As Freud famously remarked, his case histories often read like novels. This, by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, does too, or more accurately, a play of his that he transformed into a film. The play (and film) are autobiographical, recounting Fassbinder’s tortured affair with Günther Kauffman, an actor in his inner circle—this really is a case history.

Fassbinder reversed the sexes, though. There are no men in this movie, except for Fassbinder himself who appears in a blurry newspaper photograph. (Remember Hitchcock’s Lifeboat [1944]?) The film has a five-act structure, marked by the different wigs and costumes Petra (Margit Carstensen) wears, suggesting the different personalities she shows to her visitors. In each scene film time simulates real time.

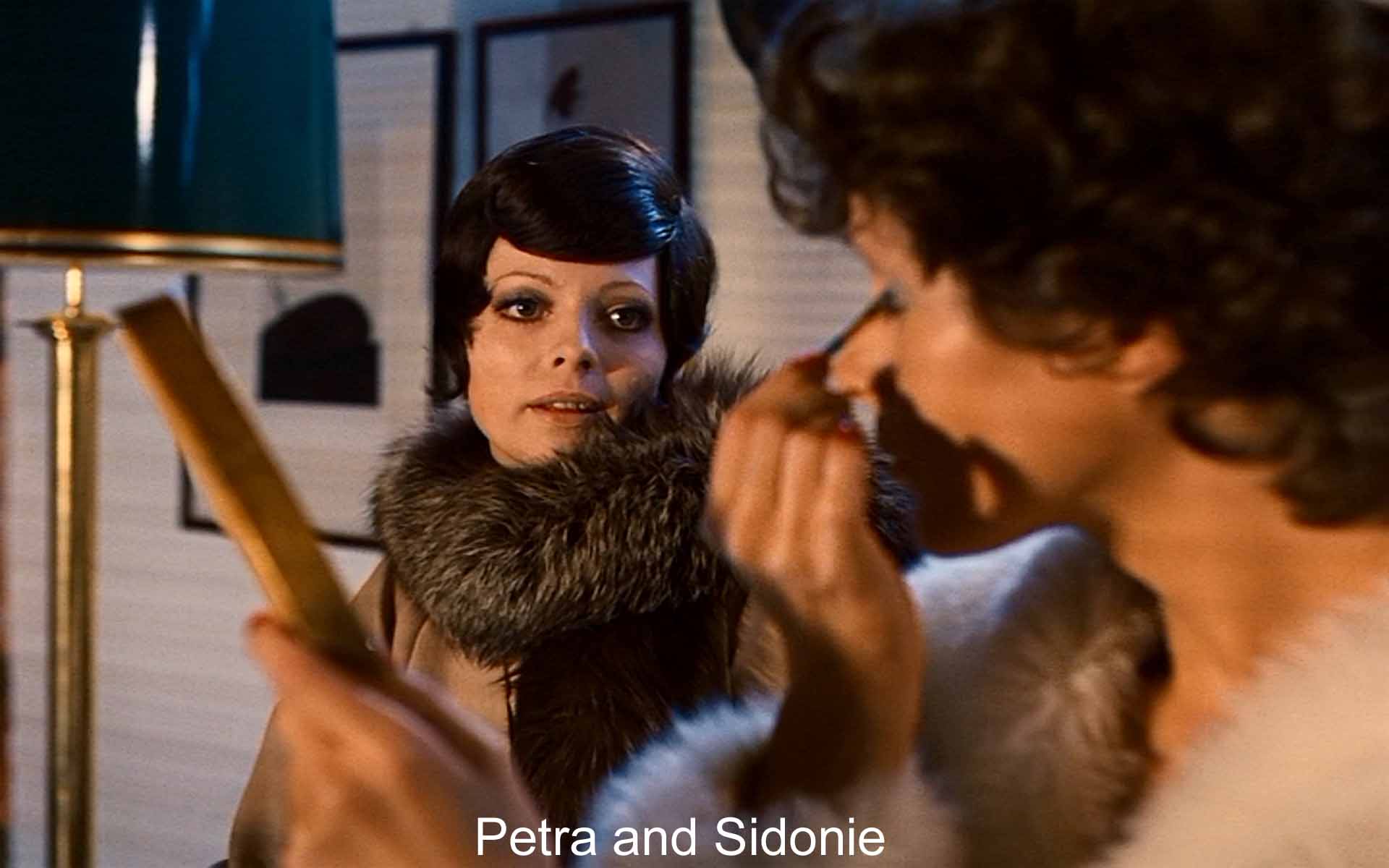

I. Brown wig. Petra awakens, phones a series of lies to her mother and orders around her slave Marlene (Irm Hermann). Throughout the film Marlene says not a word, but comments by her expressions and the noise of her typing. Petra puts on a fancy peignoir and gets a visit from an aristocratic friend, Sidonie (Katrin Schaake). Sidonie watches as Petra creates the beautiful, fashionable Petra von Kant from a rather homely thirty-five year old woman who does not look her best when she has just woken up with a hangover. Sidonie married an aristocrat, and she tells us how she finagles from her husband the wealth and fashion that Petra has had to work for. Petra’s two marriages ended badly, one by an auto accident, the second because Petra was more successful than her husband. Sidonie then introduces blond and somewhat sleazy Karin (Hanna Schygulla). Petra takes a fancy to her, inviting her to the apartment a couple of nights later to discuss a career in modeling.

II. Black wig. Karin returns for that evening visit, and in a long discussion Petra uses her money, prestige, and power in the fashion industry to tempt Karin into a modelling career and lure her into a lesbian relationship. The gowns the two women wear are telling. Petra’s skirt hobbles her so that she has to walk tippy-toe. Karin’s suggests a steel breastplate. Petra feigns weakness; Karin feigns strength. Marlene types noisily throughout the seduction, telegraphing her disapproval of the goings-on.

III. Red wig. Power has shifted from Petra to Karin (paralleling Petra’s second marriage). Petra is suffering and drinking too much. Karin now cold shoulders her and finally leaves, rejoining her previously abandoned husband. Petra is devastated.

IV. Blond wig. Dressed for bravado in bright green with a bold red flower at her neck, Petra is trying to celebrate her birthday. She desperately grabs at the phone, hoping for a call from Karin. Her daughter Gaby (Eva Mattes) and mother Valerie (Gisela Fackeldey) now arrive. Petra scorns them, calling them spongers. Sidonie shows up and gives her a doll with a startling resemblance to Karin. Petra grabs at it. She cruelly insults them all and collapses.

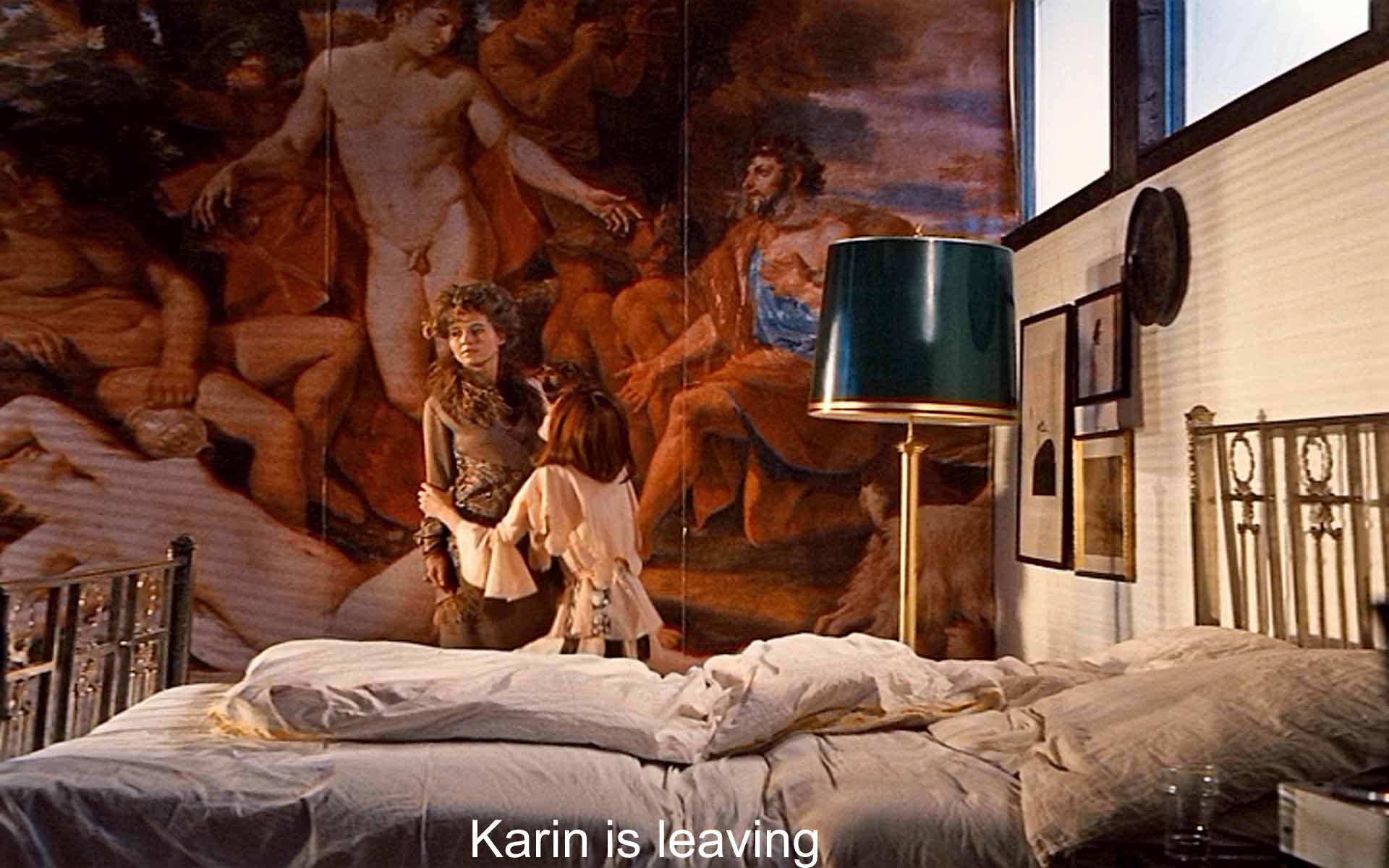

V. No wig. The huge painting so obvious in the previous scenes is out of frame. Petra is lying in bed (as in the opening shot), recovering from her collapse, her mother at her side. Now she reforms, saying she didn’t really love Karin. She only wanted to possess her (as she does Marlene). She makes up with mother and daughter and offers to work with Marlene as an equal.

Although I don’t believe in “spoilers,” I’ll not tell you the finale, which I think spells out what Fassbinder wanted to show in the film as a whole. One of the actresses phrased it in the Criterion DVD’s interviews, “the oppression of women by their feelings.”

Fassbinder seems to me to be saying that there can be no love without one partner using that love to dominate the other (particularly sadomasochistically). As a famous quotation has it, “Always in love, there is one who loves and one who is loved.” Well, maybe. I can put it in blander terms: In order to love one must open up, be vulnerable, which means possibly being wounded. The film gives us Fassbinder’s various examples: Sidonie’s subtly managing her dominating husband; Petra’s second marriage collapsing when her husband can no longer dominate; Petra’s loveless relations with her powerless and penniless mother and daughter; and the center of the film, the shift in power relations between Petra and Karin, a shift achieved by Karin through men. No domination, no love. And this comes through most strongly in the enigmatic ending.

If you believe in spoilers, skip the next three paragraphs. I don’t. If knowing the ending spoils a movie, how could we see a movie twice? How could we see a movie based on a well-known novel? How about the old days of the double feature when we often saw the ending first? Anyway . . .

In the finale, Petra has reformed. No wig. She is back in her bed, as at the opening. The film comes round. She tells Marlene that she is sorry for the way she has treated her. From now on they will work together as equals. In response, Marlene pulls out a suitcase, loads it up with her belongings adds a pistol and the Karin doll and leaves, never saying a word. This is a change from Fassbinder’s autobiographical play. There the Marlene (to whom this film is dedicated) stays with Fassbinder-Petra, and there is a possible reconciliation between the two women.

Needless to say the puzzling ending has called forth comment. There is an optimistic reading: Marlene doesn’t believe Petra’s reformation. It’s supported by the music on the soundtrack: “The Great Pretender” by The Platters. “Oh-oh, yes / I’m the great pretender / Pretending that I’m doing well.” That leaves Petra falsely nice, and Marlene escaping the sadistic domination that will continue despite Petra’s lies. But this seems shaky: If Marlene doesn’t want to be dominated, why didn’t she leave before?

Eva Mattes cites the director in one of the interviews on the DVD, “[Marlene] leaves, in Fassbinder’s view, because she can’t stand no longer having to submit to her lord and master and get an occasional beating. She has gotten so used to taking pleasure in it that she doesn’t want to do without. She doesn’t want to change.” I read the ending about the way Fassbinder does. Given that there is no love without domination, when Petra ends her domination of Marlene, Marlene knows that she has lost the love of Petra, and she leaves. Hanna Shygulla says of Fassbinder in another of the DVD’s interviews, “It haunted him, that even in love, one is stronger and the other is weaker. In his opinion, the stronger is the one who loves less.”

Love and sex provide one kind of domination, class and money another. Thus Petra feels dominated by Sidonie (who can cruelly give her that Karin doll), but she dominates worker-bee Marlene and her penniless mother and daughter and (for a time) Karin. Power and domination permeate Fassbinder’s world. I find parallels in philosophy: Kant, venerated in Germany, whose focus on personal experience could authorize Petra’s selfishness; and Michel Foucault, so popular in the 1970s, who proclaimed the omnipresence of power and domination in the intellectual and social spheres and whose sexual life mirrored that domination.

Why the Karin-doll and the pistol? One is the emblem of love, the other of hate. Together they spell ambivalence, the primitive divided and conflicted feelings that underlie and color all subsequent emotions (in psychoanalytic theory with which Fassbinder was familiar).

But whether you agree with Fassbinder’s bleak world-view or not, what matters is the consummate artistry with which he presents it. It is astonishing that he could finish this film in ten days, but that was what he liked to do. No more than three takes for any scene. Despite the haste he drew astonishing portrayals from Margit Carstensen, the craftily seductive Hanna Schygulla, and Irm Hermann (even though she is mute throughout!). Shooting in this small claustrophobic apartment with no movable walls would have been impossible without the great skill of Michael Ballhouse, his favored cinematographer (who now works with Martin Scorsese). According to the actresses, the two worked closely together to the exclusion of other members of the crew.

Then there’s the all-too-apt music. In Act I, Petra gets out of bed and starts playing the Walkers’ treacly version of “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” so that she can slow dance with the obedient (and silent) Marlene. The song foreshadows the break-up of the coming affair with Karin whom we’ve not yet seen. When Petra finally collapses (in the scene with mother, daughter, and Sidonie), Un di felice from La Traviata bursts out with its concluding lines about love: “torture, torture and delight / torture and delight, delight to the heart.” Then there’s “The Great Pretender” that contradicts Petra’s reformation. The overstated music corresponds to the kitsch, the “gloss,” the overstatement that runs all through this film. Fassbinder exaggerates, undercutting his own film in its costumes, set, make-up, music, mirrors, etc. as if to act out his own sadomasochistic identity in his film style.

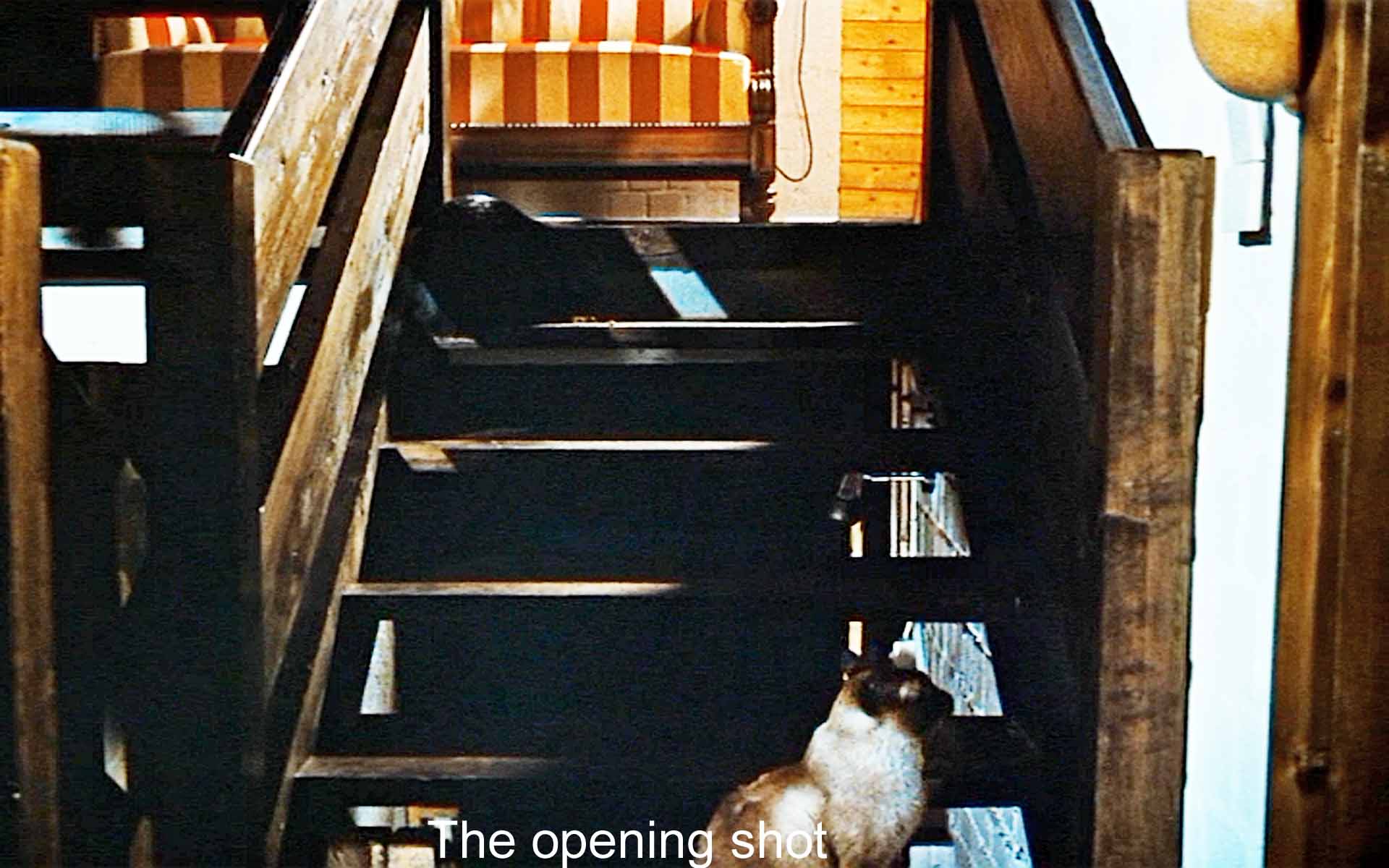

Fassbinder is a master at adapting the mise-en-scène to his own psychological issues, the doors in Fear Eats the Soul, for example, or the succession of eating and drinking scenes in Maria Braun. Fassbinder is a master, period. Here, the opening shot tells us the importance of his inspired set with its staircase, half sofa, hidden rooms, low beams, all suggesting the twisted and twisting world of Petra and the others. The two cats suggest the catty relationship that will develop. And the painting! We see the mute and slavish Marlene. Dolls on the beams suggest both the love and the total control that Petra has over most of the other characters. Then there are the naked mannequins moved here and there in response to the shifting relationship. Marlene uses them and a drawing on an easel to work—she is the only one who does any fashion work at all.

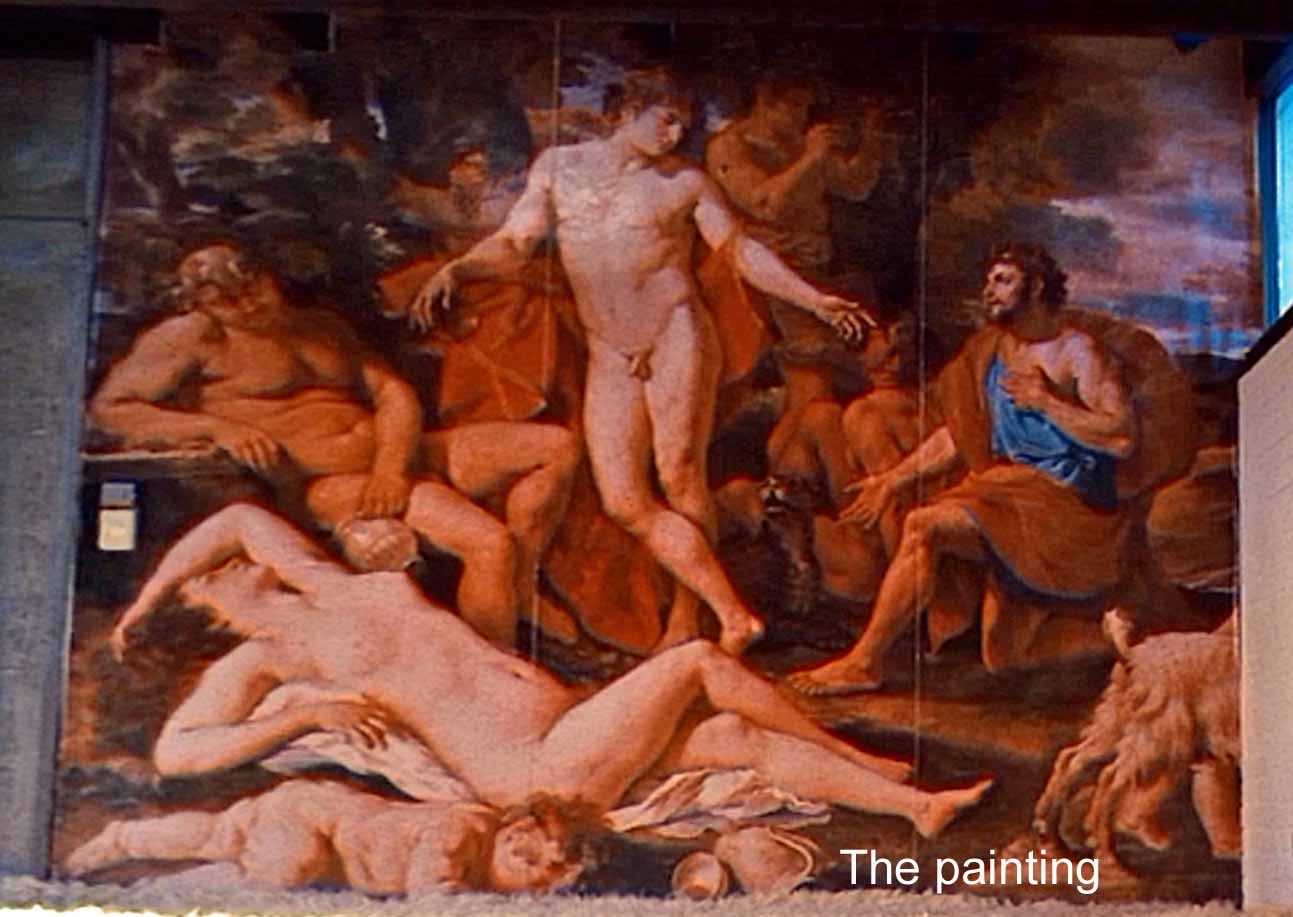

Strangest of all is Fassbinder’s amazing use of the wall-sized painting that shows one with power, one without, in a context of debauchery. What dominates most of the scenes is a huge blow-up of a painting that in its un-filmed state is only about three feet by four feet. It is Nicolas Poussin’s Midas and Bacchus (1629), illustrating the story of Midas. As told by Ovid, the legend was adapted into plays by Mary and Percy Shelley and more recently by Mary Zimmerman (and this version was performed at UF in 2014).

The young Bacchus (or Dionysus, god of wine) was being tutored by old Silenus (the party-god) when Silenus wandered off. Found by Midas, the king entertained him lavishly for ten days until Bacchus took charge of the old man. In the painting, the nude woman lying in the foreground, the old man Silenus asleep behind her, and the putto with goat in the lower right corner represent a post-party scene. Bacchus was grateful to Midas for his hospitality and granted him a wish. Midas wished that everything he touched would turn to gold. He touched his daughter—oops! Petra is a kind of Midas. She strikes gold in the fashion world (as in the phone call she gets early in the picture). But she loses the one she loves.

In the center of the painting, a nude Bacchus stands, listening to a kneeling Midas’ plea to reverse the awful wish. He apparently tinted it more red, perhaps to suggest passion. Interestingly, Fassbinder cropped the painting to remove an inset against its right border which shows Midas being cured. In Fassbinder’s world there is no cure. There is no love, only power, pain, and domination.

You can hardly miss, in the figure of Bacchus, his genitals, and in scene after scene, Fassbinder highlights them. For all the rampant femininity in this film totally populated by women, male power is always present. We certainly hear male domination in Sidonie’s advice when she suggests achieving power by weaseling with womanly wiles and weakness. Petra, of course, indignantly rejects this idea. She is powerful in her own right, at least at the beginning. But looking down at her is this nude Bacchus.

If he had done nothing else in this film but use this painting as he did, we would have to say he showed an extraordinary imagination. But this is a film with overpowering emotions, a set that says it all (or most of it), an unforgiving world-view convincingly demonstrated, obsessive romance, philosophical density—you name it. Strange, tortured Fassbinder was a brilliant, writer-director. He ranks among the very best.