There is no plot in this film. Nothing happens. Well, two people die, but there’s no plot in the sense of a hero questing after treasure or two rivals competing for a lady fair. This lack of plot led the film’s early reviewers in the West to read it as a documentary in the Flaherty tradition and write about the accuracy with which Satyajit Ray portrayed village life in India. They seem not to have known that this film and the two later films in the trilogy are based on a hugely popular novel, Pather Panchali by Bibhutibhushan Banerji, a book virtually every Bengali would have read. One needs to read Pather Panchali as a feature film, a story-telling film, not just as a filming of real life.

Today one finds critics raving over the “humanism” of the film or its “sincerity,” “serenity,” “nobility,”, “intensity,” and so on. But very little gets said about Ray’s particular choice of details. How does the insert shot of waterbugs skittering across the surface of a pond fit into the film as a whole? (Perhaps: the pond as a protective, concealing surface, as it will be in the finale.) The praise for Ray’s work is sky-high, but recognizing the unity in this film is non-existent.

Although there is no date indicated, Pather Panchali / Song of the Little Road is set in 1910. The opening shot shows a woman on a rooftop watering a potted plant, apparently in some kind of religious ritual. But this is not the wife, Sarbajaya, who is the heroine of the story (Karuna Banerjee). This is her nasty, richer neighbor, a relative. The wife we will see in a moment watering a scrawnier plant, beginning a persistent contrast between rich and poor. But first the nasty rich neighbor spies from her rooftop the daughter Durga of the poor family (Uma das Gupta) stealing fruit from her orchard, an orchard taken from the poor family by legal finagling.

Already Ray has begun developing the various axes along which he will visualize his story. Religious tradition, possession, who owns what, rich and poor, the economic necessity of getting and spending—that’s one. High and low—the physical relation between objects. The village as opposed to the nature that surrounds it. The family’s name is Roy, and like their creator the husband is descended from writers and scholars, people of words and abstractions embodied in this father, Harihar (Kanu Banerjee).

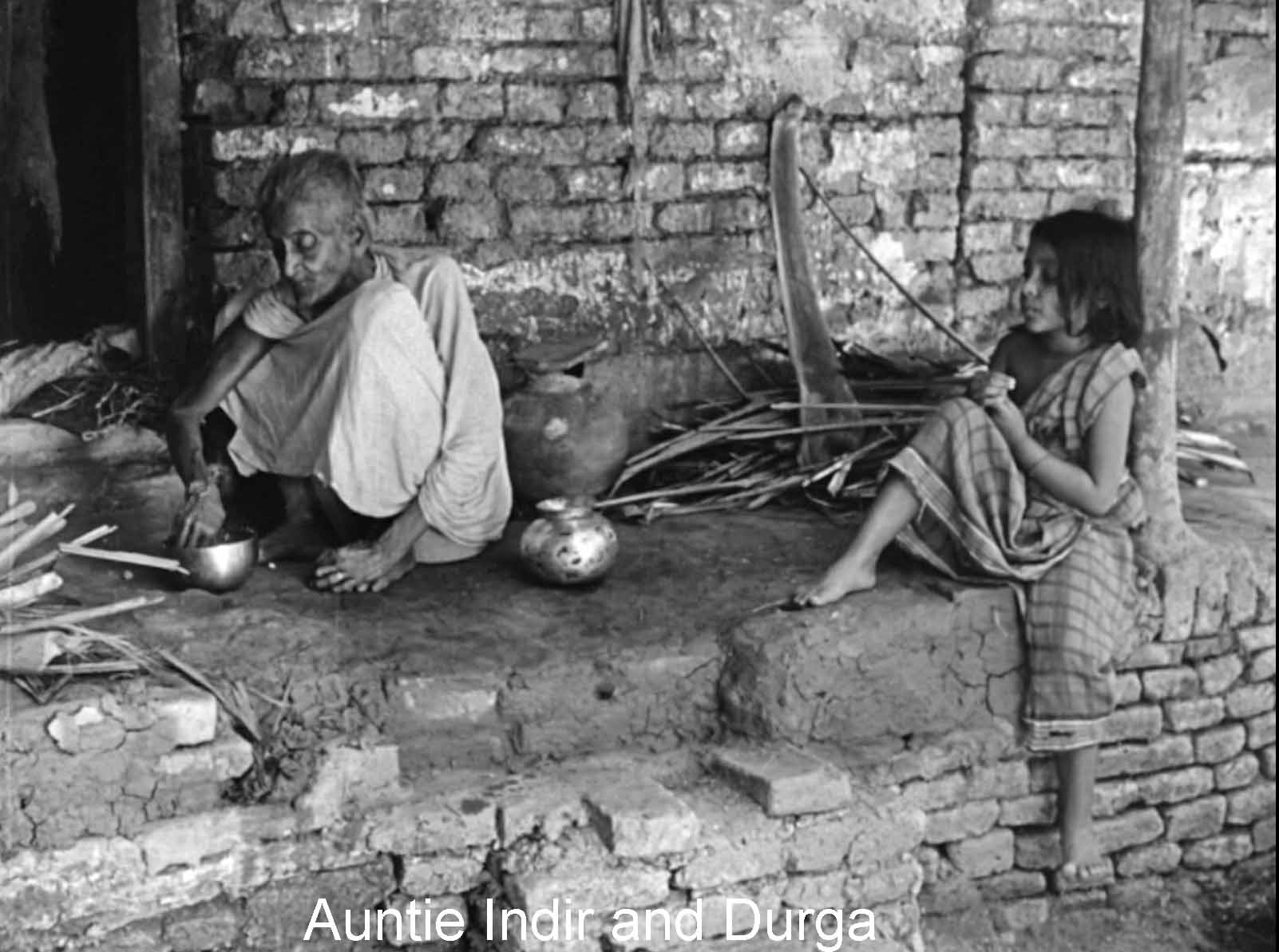

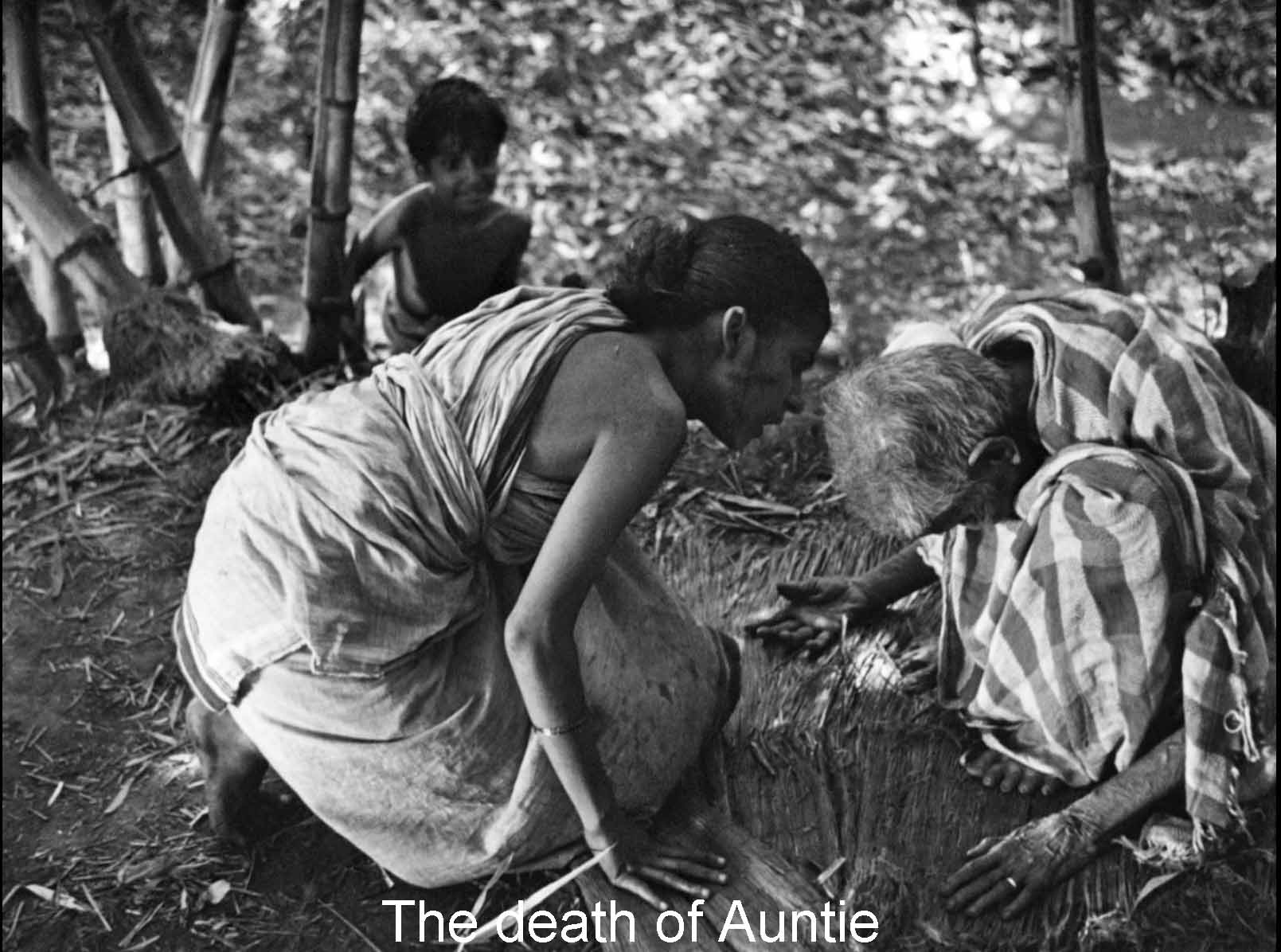

Watering a plant is nurturing physical growth, and water throughout this movie is a life force that will propel Ray’s story through the three films of the trilogy. And that same growth and forward movement tells us ancient Auntie Indir Thakrun (Chunibala Devi) represents all our agings. As if to signal her obedience to that life force, she goes out into nature to die.

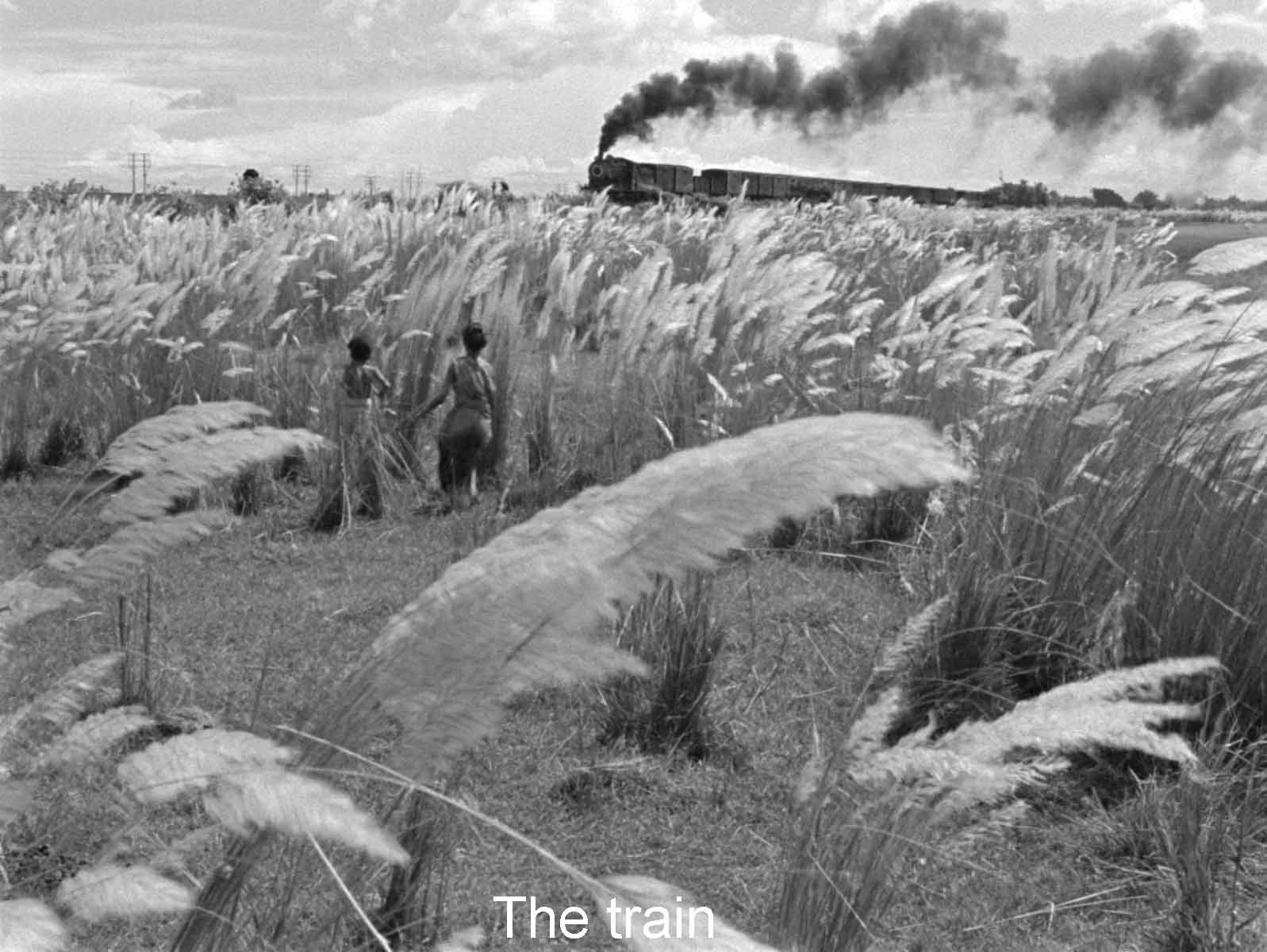

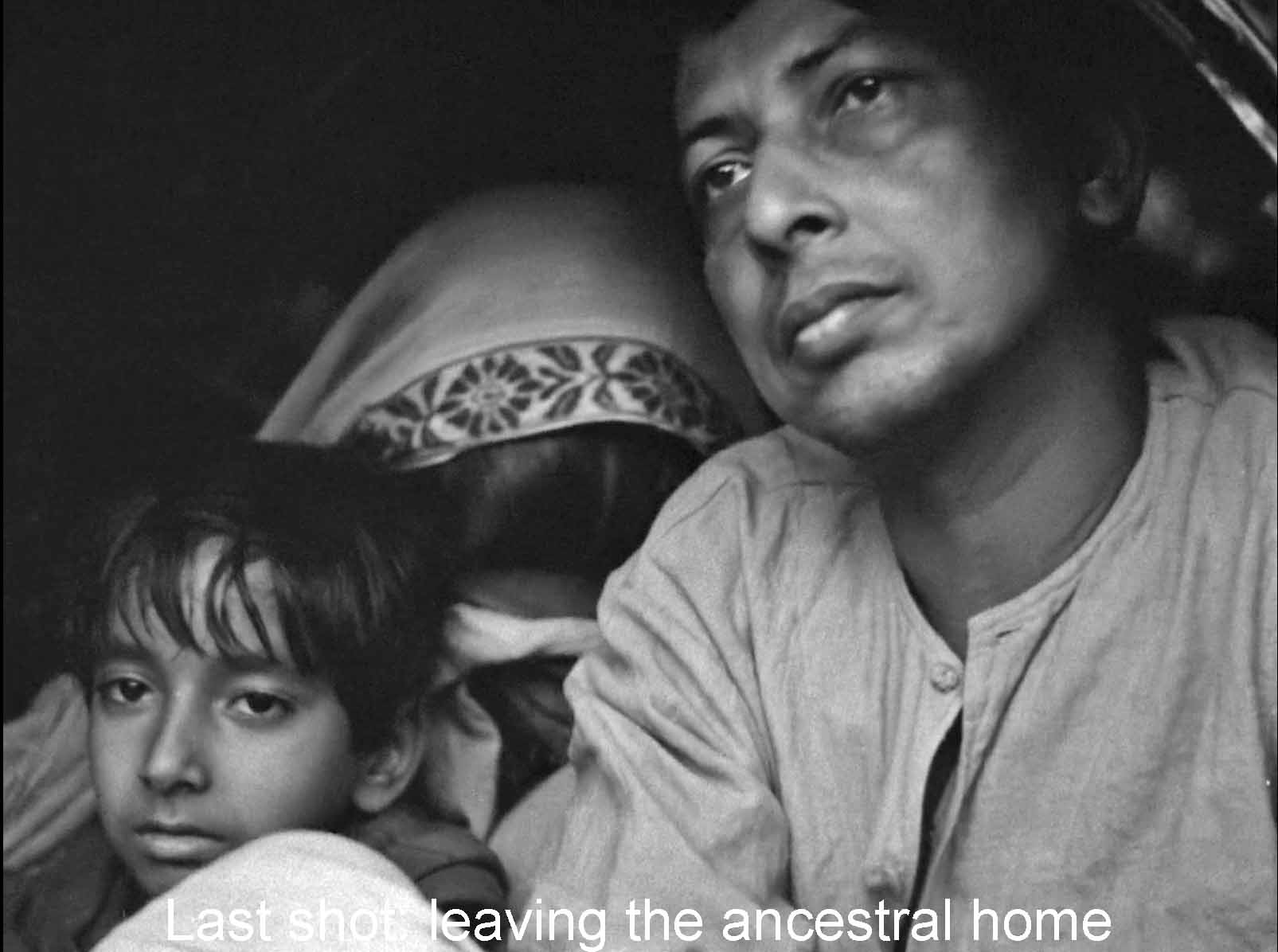

The mere physical position of objects indicates high and low, rich and poor, in nature or in the family or in society. But all through the film nearness and closeness will comment on the human relationships. The father Harihar (Kanu Banerjee) is descended from scholars and poets. He scarcely touches his wife. His five-month absence physically comments on his other-worldly plans to support the family by priesting and playwriting. The children run off from the family mired in tradition and hear the hum of power lines and see and hear the roar of a train—and then find dead auntie. The episode speaks not only to a life force but to the progress Prime Minister Nehru wanted for India and also the physical and sorrowful distance between the traditional village and a hoped-for modernity. The finale, physically leaving the “ancestral home,” describes the emotional and symbolic leaving as well.

In short, Ray uses the ordinary physical components of a film, distances, perception, motion, possession, eating, food, chat, to physically embody the emotional and intellectual aspects of his story. The shopkeeper-teacher (Tulsi Chakravarti) neatly embodies Ray’s tactic. He dictates classical poetry for his students to transcribe while he sells food and collects money—he acts out the real poles of life in this village, tradition and trade. And his students, instead of transcribing poetry, play tic-tac-toe—so much for tradition and the young. Young Apu watches both actions, wide-eyed and amused, and that is another major component of the life Ray is building, perception.

The first thing we see of the boy Apu is his big, brown eye. Again and again, we see events not only through the all-seeing eye of the camera, but we see the characters seeing them: Apu watching the play or the military band or the boys playing tic-tac-toe; Durga watching Auntie eat; the children seeing and hearing the train and electricity; spotting the candy-seller; Apu watching Durga drench herself in the monsoon; Durga’s face as seen by the kittens, and on and on.

Why the kittens? Their unself-conscious tumbles and swats contrast with the humans’ all too painful consciousness of their situation. Yet the kittens seem not symbolic but simply there. So with the shots of waterbugs and water lilies on the surface of the pond—water as supporting and sustaining. In the finale, a snake occupies the deserted house, echoing the evil serpent-god in the play. Again, it is simply there, and Ray leaves it up to use to see the connections.

The act of perceiving, however, ours and the characters’, is a major axis along which Ray creates his film. We get it at the very beginning when the nasty neighbor spies Durga stealing fruit. We get it in the final shot of the family looking ahead to a doubtful future. We first see the boy Apu as a big brown eye, and again and again we will watch him perceiving: the grocer-schoolmaster, the play, the band, the rain drenching Durga, his father’s grief, the stolen necklace and his concealing it forever.

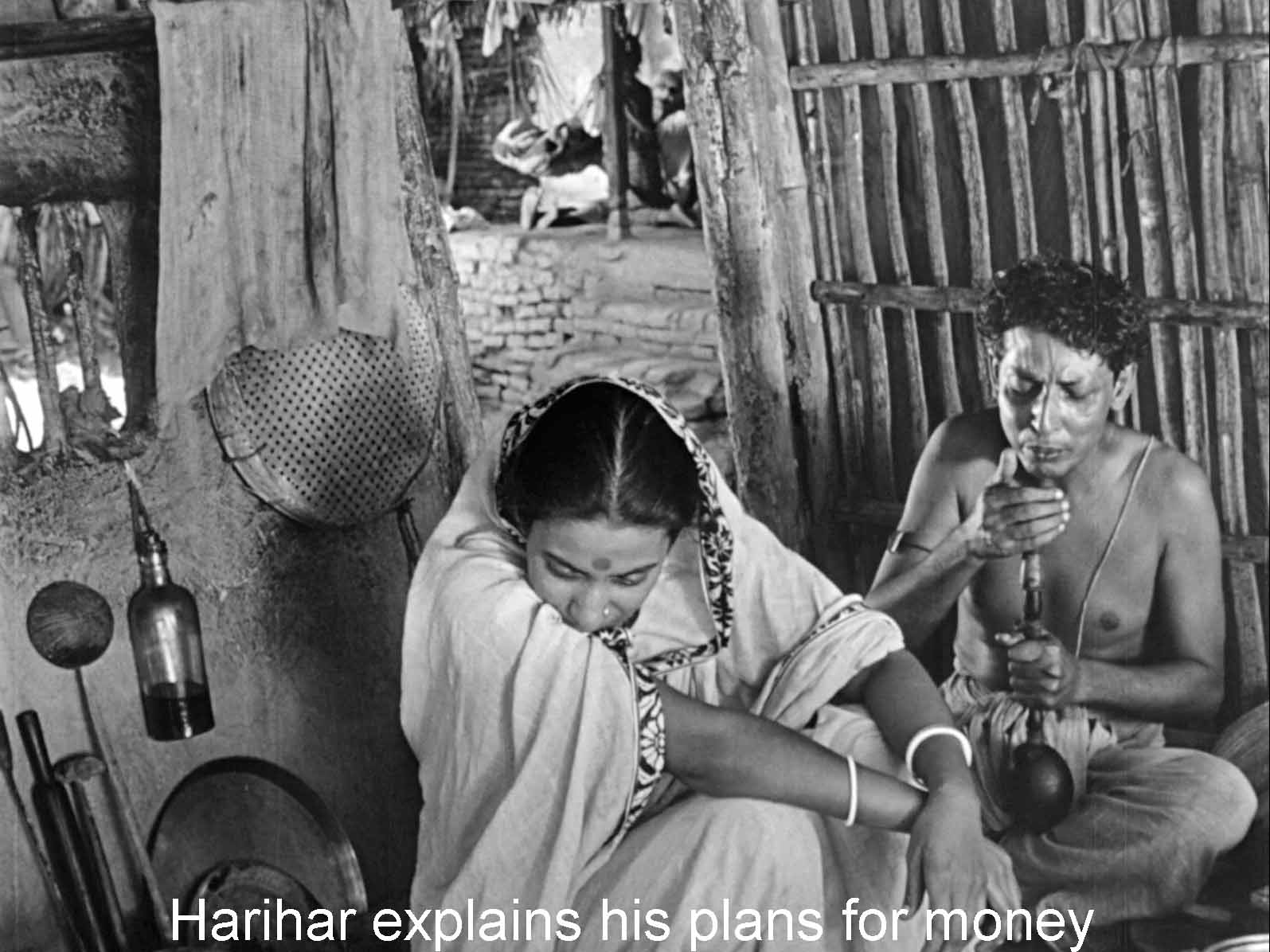

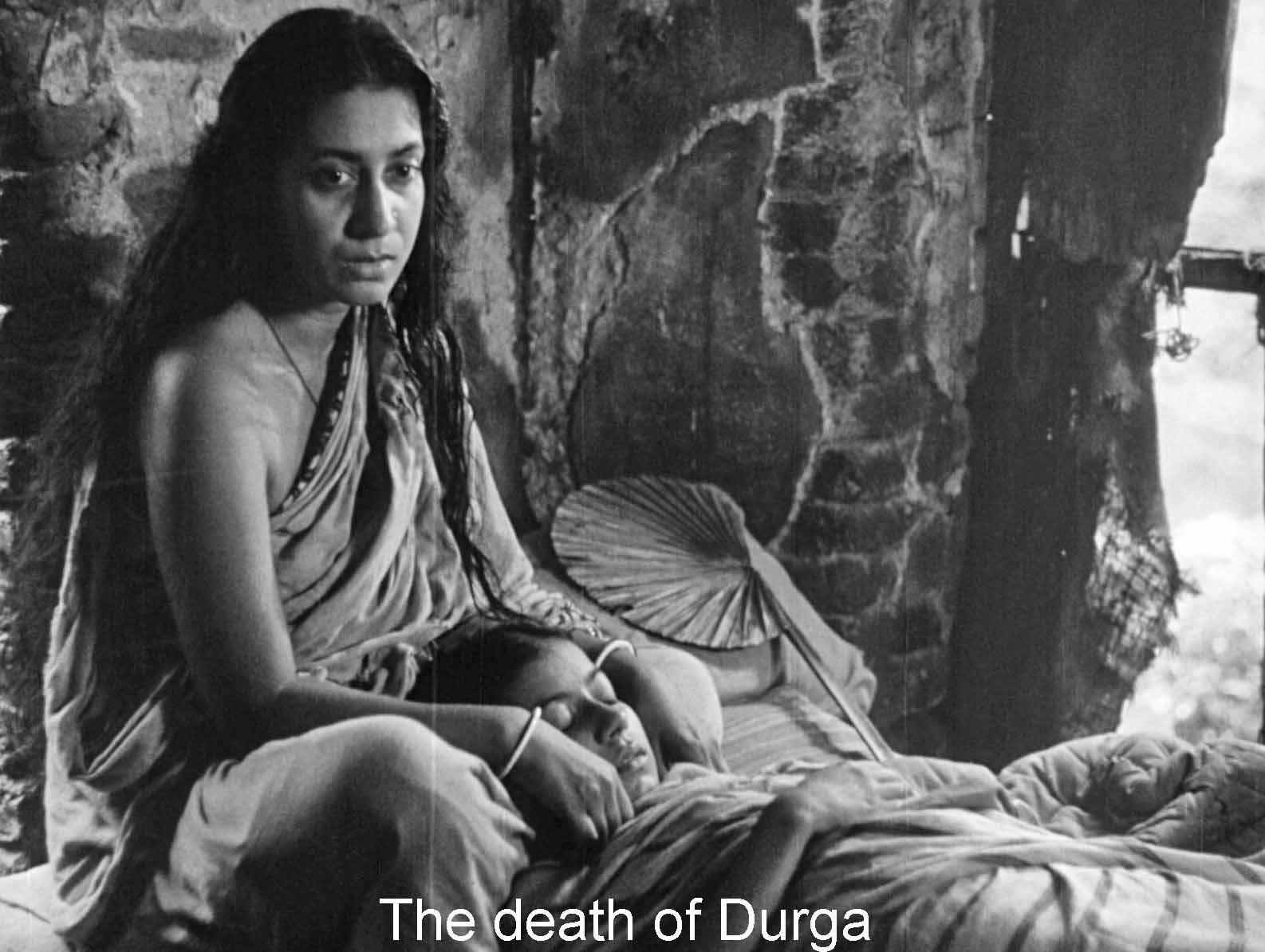

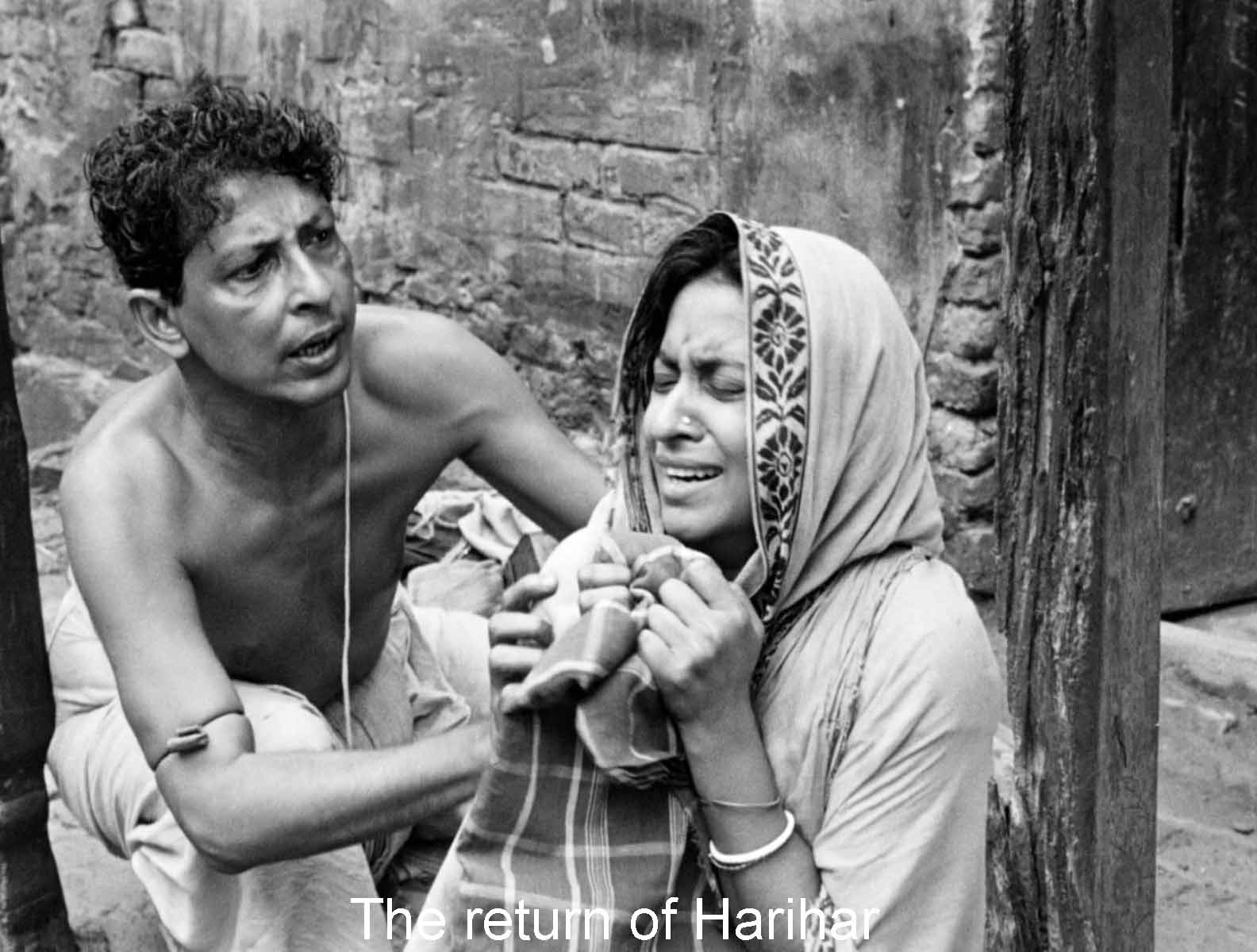

Another recurring element is the contrast between the tangible demands of life and the father’s airy plans. As he smokes his pipe, he describes his vaporous schemes to support the family by writing plays and conducting religious ceremonies (he is a Brahmin). This is all very abstract and papery compared to his wife’s all-too-physical need for food, repairs to the house, clothing, and so on. His abstractness translates to his absence during the storm that crashes down on the house and during Durga’s dying. Eventually his novel is eaten by worms.

Another theme is eating and food, made visual in the constant toil and worry of the mother. And perhaps we can think of eating as the ultimate possession, for possession—who has what, to whom does it belong—is another preoccupation of the film.

These three themes (and there are no doubt others) one arrives at by responding to elements that are repeated or contrasted. But Ray has another, more unusual style. His other method is to use the ordinary elements of film, the subject-matter on screen (for example, some kittens or a field of grain), the placement of characters, perspective, camera position (close up or far away), sound track, still camera or moving camera, high key or low key to say something subliminally about the characters on screen.

These perspectives on his story Ray creates without calling attention to what he is doing. The exception is, inevitably, the music which, like all non-diegetic music in films, was added on specially. The music was composed by Ray himself and the great sitar player, Ravi Shankar, in one fourteen-hour night session. Those who know Indian music better than I can link the various traditional forms and instruments to the moods for the various episodes. But here again, he is commenting almost subliminally on the characters and the action.

Aside from the music, Ray takes the ordinary stuff of film imagery: distances, perception, close-ups, events, and imbues them with the story he is telling. In a sense any filmmaker does that, but most filmmakers are more deliberate, shaping and highlighting certain elements of plot or particular images on screen. Ray simply films, but we can read the ordinary elements of his filming as commenting on the life of this family (and all families). I think this is what people mean when they say that Ray’s movie shows life itself, that is, not themes, not ideas about life, but just life—whatever that means.

Critics go on about Ray’s “humanism,” his “sublimity,” his “humility,” etc. He has made the ordinary stuff of filmmaking into the significance, the universal application of his story. His is indeed an extraordinary achievement, quite unique, even compared to his later, more conventional films. Perhaps only a novice could have done it. This was Ray’s first film—he had worked for years as an illustrator—and his crew also had little or no experience making a movie. They lacked the devotion to artifice of the conventional filmmaker. That, I think, is why they were able to see their story as not separate from the ordinary devices of filmmaking. The result is extraordinary, a unique and wonderful achievement in the history of motion pictures.