Fictions within a fiction. That’s what Graham Greene, the screenwriter, and Carol Reed, the director, have arrived at in this splendid comedy, a farce that evolves into menace and murder, all of which, we find out in the end can be laughed off.

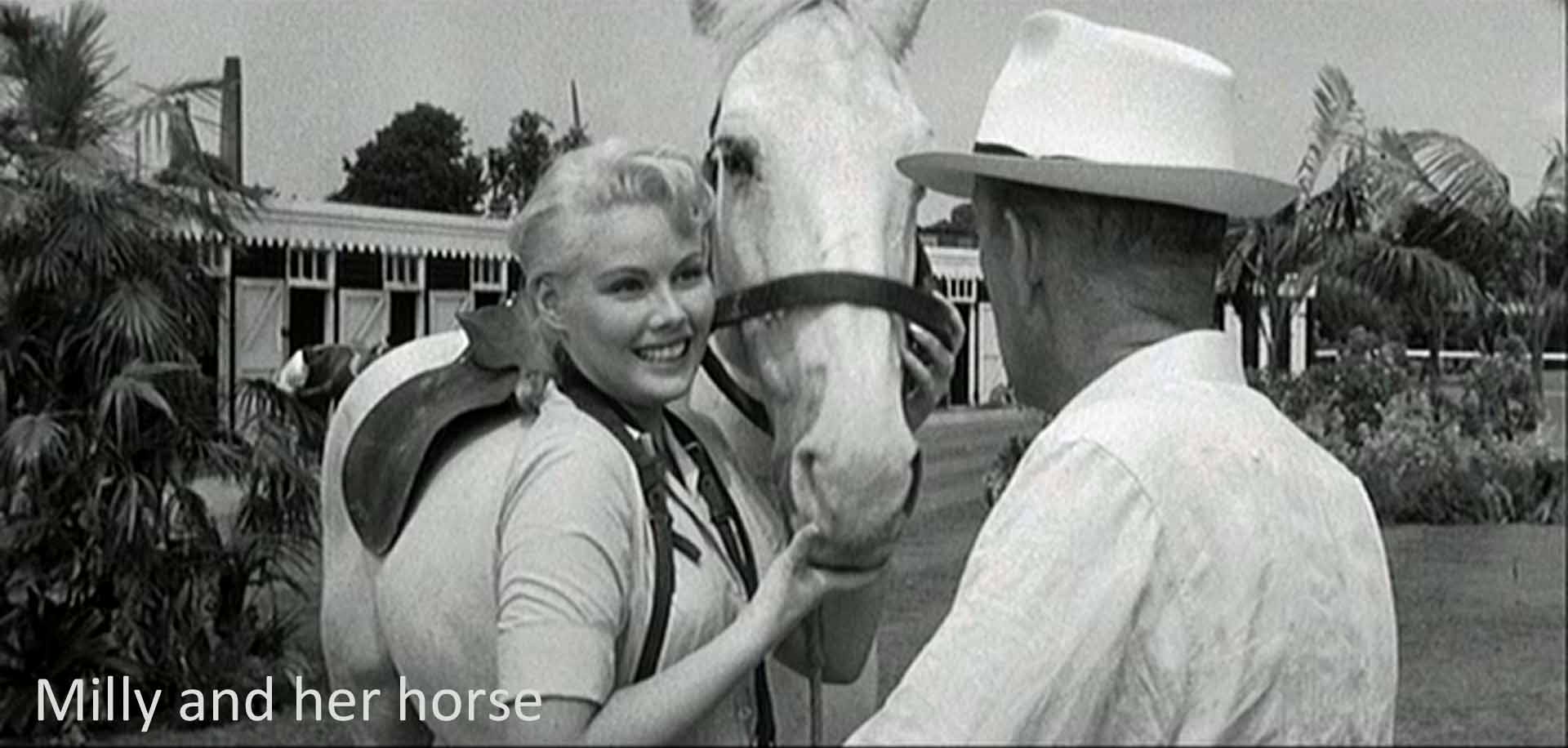

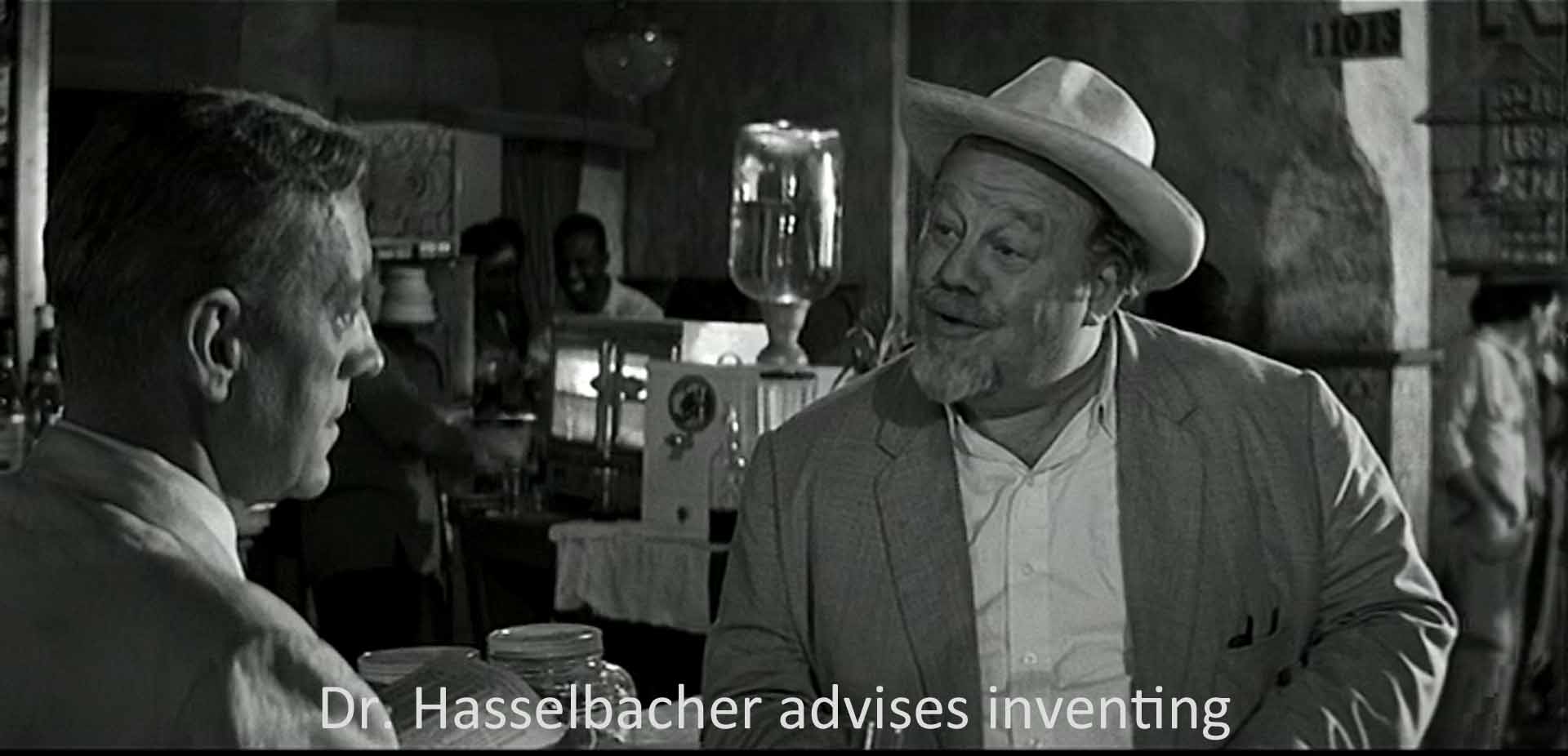

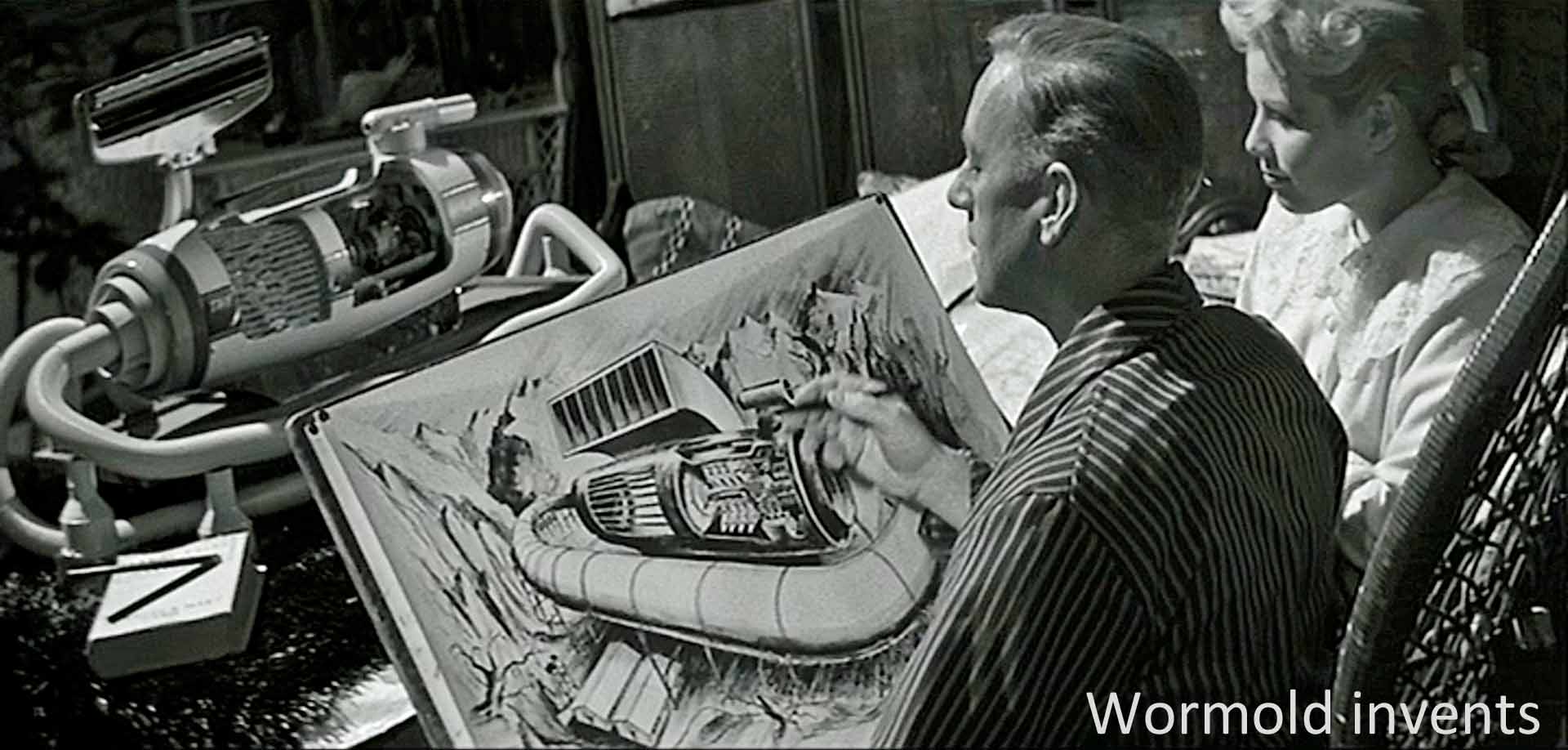

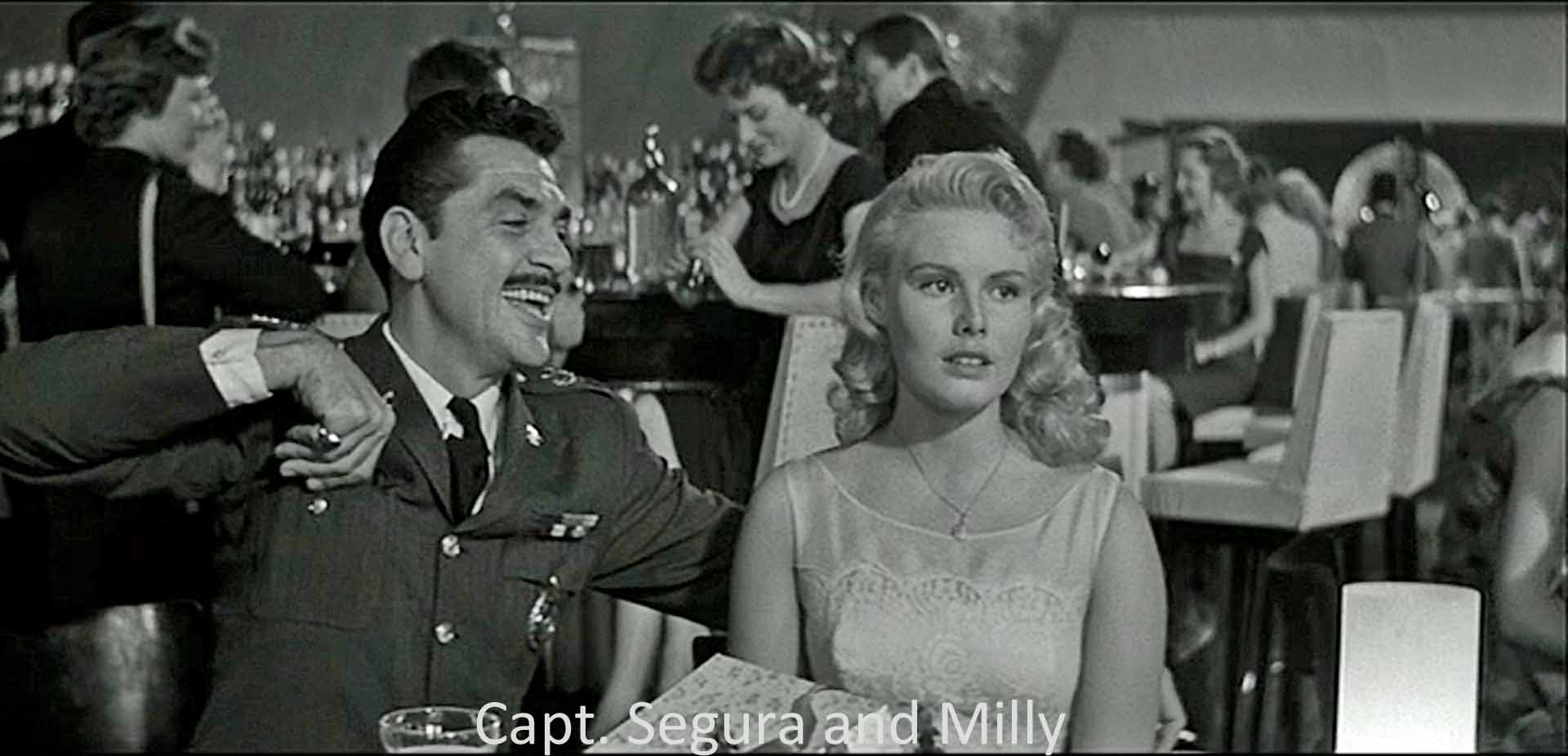

Hawthorne, an exaggeratedly British Noël Coward, recruits vacuum cleaner salesman “Mr. Wormold” (Alec Guiness) to be the Havana man in his Caribbean spy network. This is Batista Havana, pre-Castro, where Capt. Segura (Ernie Kovacs) is the enforcer and torturer for the dictatorship. Wormold becomes a spy to get the money he needs to satisfy his daughter Milly’s expensive tastes (Jo Morrow). But he also wants to get her out of Havana where Capt. Segura plans to marry her. Wormold is baffled as to how to perform his duties as a spy, recruiting sub-agents, sending in reports, and so on. To earn his money, Wormold takes random names out of a list of country club members for sub-agents and produces drawings of a massive secret weapon in the mountains with a strange resemblance to a vacuum cleaner. The spymasters in London, led by “C” (Ralph Richardson), are both delighted and alarmed by the information. They reward him with a radio operator and a beautiful secretary, Beatrice (Maureen O’Hara). But things go bad. Dr. Hasselbacher, Wormold’s best friend (Burl Ives) is threatened into spying on him. A real airplane pilot, Montez, who has the name of Wormold’s fictitious pilot, supposedly spying in the mountains, is killed. Another invented spy is tied up and dumped on Wormold’s doorstep. Hawthorne tells Wormold that he himself has been targeted. Wormold manages to foil his would-be murderer, Carter (Paul Rogers), another overly overt British spy, but his friend Hasselbacher is killed instead. In retaliation, Wormold kills Carter, but overwhelmed by the deaths, he confesses his fictions to Beatrice, whom he has come to love. She returns to London and reports them to the head of the Secret Service. Capt. Segura deports him from Havana to London where he and Beatrice face the wrath of the spymasters, and that turns out to be the most outrageous fiction of all.

The film has a lot of the things one expects from Reed. Many camera shots are “Dutch angles,” tilted, suggesting that things are askew. Animals: the horse Milly loves; the dachshund killed by the poison intended for Wormold. Children: the beggar boy. And this is very much a city film with lively scenes of street life in Havana. It is a divided city like the Belfast of Odd Man Out or the Vienna of The Third Man. Like the London of Oliver!, it is divided into an upper class (the penthouse, the country club) and a lower class of street people.

The film deals in loyalty. Hawthorne plays on Wormold’s 1939 enlistment for Britain in World War II to get him to spy for Britain. The Secret Service people are also loyal to their country (and its traditions!) in their bureaucratic way. Hasselbacher dons the uniform he wore in the Kaiser’s army. And there is betrayal: Hasselbacher lets himself be used by “the others” to threaten his friend Wormold’s imaginary spy network. “The others” plan to murder Wormold. And as in Reed’s three masterpieces, we have an innocent who creates disaster. Wormold with his fictional spy ring causes the deaths of Montez and Hasselbacher. Ironically, it was Hasselbacher who said, “As long as you invent, you do no harm.”

So we thought. Ultimately, death turns the fictions and play-acting into grim reality. The big fictions are, at first, Wormold’s made-up spy ring and his imagined secret weapon. But there are lots of little fictions. Wormold pretends, at various times, to be Hawthorne or a clown or a rich country club type or a spy or a master checkers player. Wormold describes himself as “a science-fiction writer.” “He was no more real to me than a character in a novel,” says Wormold of murdered Montez. As if he understood Wormold’s play-acting, Segura tells Wormold, “You’re playing the wrong character.”

The other characters pretend, too. With his inane precautions, the all-too-obvious Hawthorne pretends to be some superspy. Milly’s pious education by the nuns seems a sham compared to the reality of that flirtatious and greedy young lady. She gets good marks in dogma and morals but is best, she tells us, at venial sin. And Mother Superior has a hearty laugh at the dirty joke Segura tells her. Carter pretends to be a vacuum cleaner salesman. Beatrice says of her ex-husband, “He was acting all the time.” And the ultimate pretense, the immense farce, comes from the “intelligence” bureaucrats in London.

Costumes are important for these pretenses, and they define the characters and their actions. Capt. Segura’s uniform defines his role as the torturer, the Red Vulture. Stricken with remorse for what he has caused, Hasselbacher puts on his old uniform from World War I. “I was not dressed this way when I killed a man. I was dressed as a doctor, and I was reading Charles Lamb.” The intelligence wonks in London have their uniforms, and “C” his striped trousers.

In scene after scene, sellers of lottery tickets appear. You’d expect that in a Latin American country, but in this film it tells us chance is important to its story. It is chance that provokes Wormold’s fictions. Presumably chance led Hawthorne to Wormold, and Wormold picks his sub-agents by chance from the country club directory. He happens to see a huge shadow of one of his vacuum cleaners, and that leads him to the idea of a giant secret weapon. He develops the pilot Montez’ fictitious crash from a comic strip he happens to see. And perhaps there is something true of life here: chance events trigger the fictions of even such talented people as Graham Greene or Carol Reed.

Then there is the codebook, Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, chosen by Hawthorne by chance. That title is itself a bit of fiction since the book was written jointly by Charles and his sister Mary Lamb, but she is omitted from the title page. Leaving out the poetry, the Lambs pretend that Shakespeare’s plots are what is most important about him. In fact the Bard lifted almost all his plots from other writers (as playwrights customarily did in his day). Most importantly, the Lambs left out the sex. That is what balances British prudery in this film, Cuban sex.

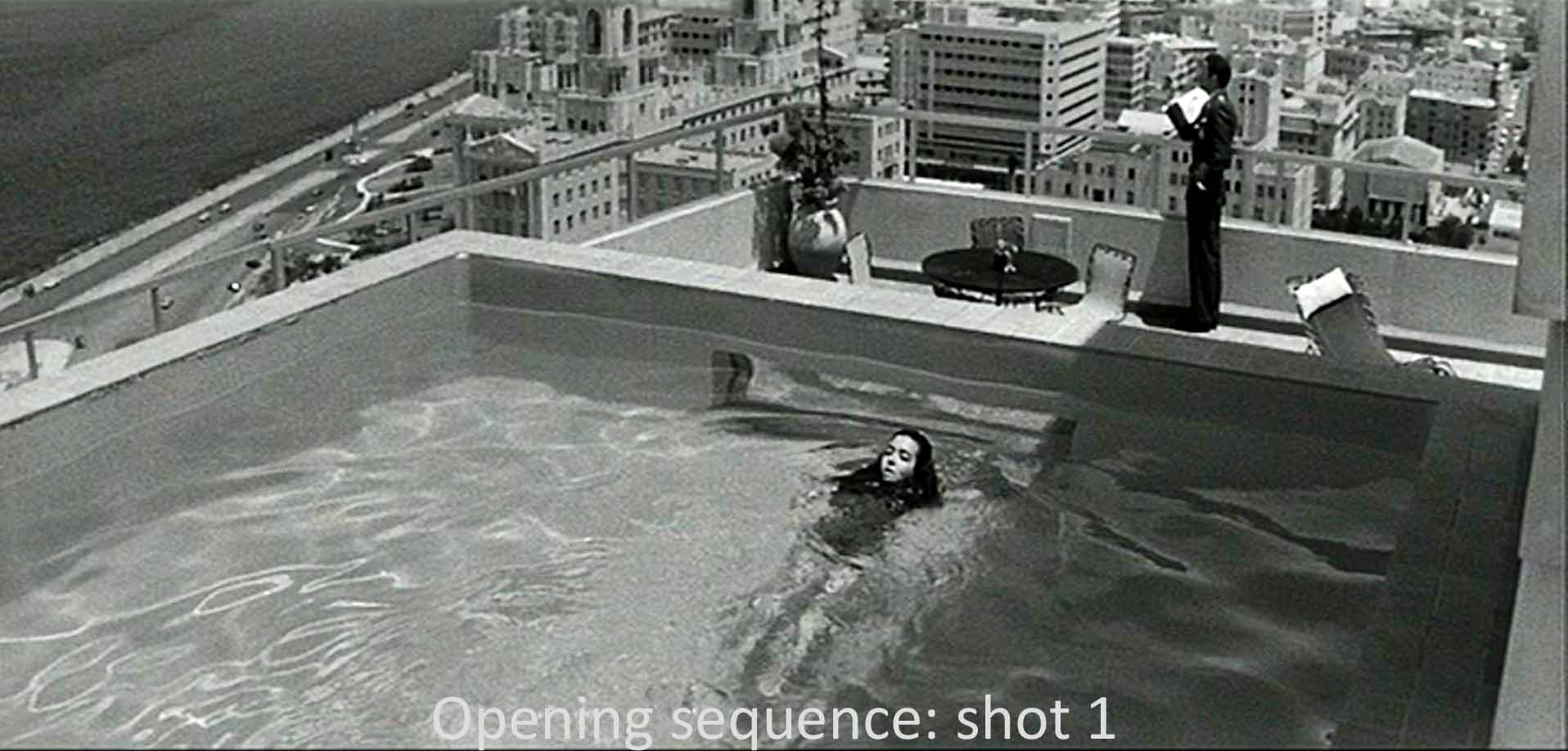

The opening sequence makes that theme clear. In the first shot a beautiful girl swims in a rooftop pool in a penthouse at the top of the city. On the deck stands Capt. Segura whose mistress this young lady surely is. The shot is setting out themes of the film: authoritarianism, of which we will see a great deal in the person of Capt. Segura.

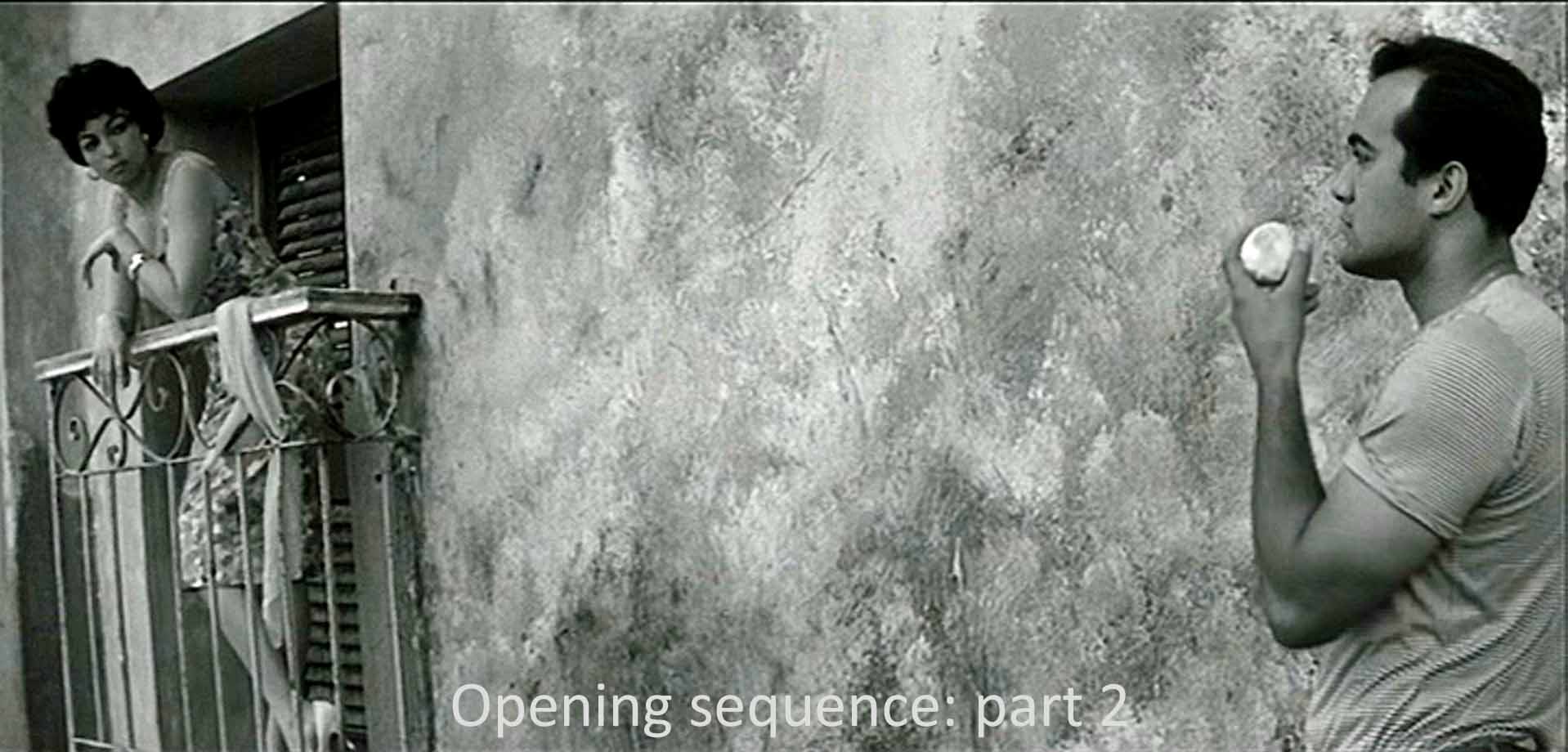

Cut to the steamy streets below (Reed's fascination with verticality) and a voluptuous woman eating an apple. She entices a muscular young man to whom she tosses the apple, telling us this is a film about the loss of innocence, of knowing good and evil, as well as tropical sexuality. Later, our hero Wormold is tempted into forbidden knowledge (of spying) and he falls. He lies (or invents), and it leads to his best friend being murdered. Cut again to the absurdly conspicuous Hawthorne who walks along, ignoring street musicians and beggars: he represents, we will learn, the inane British efforts at espionage.

As for British sex, when Hawthorne tries to recruit Wormold, he invites him to a men’s room with many hints of a homosexual pick-up (recapitulated later when Wormold tries to recruit a man at the country club). When Wormold is trying to trap Carter, another conspicuously English spy, he takes him to a seedy nightclub where Carter cannot undo a stripper’s bodice and flinches at the idea of going to a brothel. Courting Beatrice, Wormold is as diffident a lover as you could find. (This is Alec Guiness, after all.) All this reminds me of the old joke about English tourists at a tropical floor show: “No sex, please! We’re British.”

The British make a neat contrast to the constant preoccupation with sex by the Cubans, the many strippers and hookers we see. Or Wormold’s assistant Lopez constantly urging various girls on him, one of them the sexpot from the opening sequence. Segura casually refers to his “demonstrated” fertility (illegitimate children) when stating his qualifications for marrying Milly. Milly announces that, in this society, she would be better off as a mistress than a wife. No wonder Wormold wants to whisk her off to a Swiss boarding school.

Less clear than the opening is the film’s close. Having been found out but absorbed by the intelligence wonks into their world of fabrications, Wormold finds himself with Beatrice on a London street. Milly spots a Jaguar and right away wants it. (She has outgrown horses, she says.) A street vendor presses a toy on the couple (will they have children?). It combines a miniature vacuum cleaner with a sparking and popping weapon. “Made in Japan.” So much for all the spying. It’s just play—or empty—a vacuum. What’s real is sex (or, if you’re British, love): Wormold and Beatrice together (and Milly longing for a Jaguar?). The rest is play-acting, fictions in costumes. Earlier Beatrice had said, “Who cares about men who are loyal just to people who pay them, to organizations. . . . Would everything be in the mess it is if we were loyal to love and not to countries?” This is the value so silently but eloquently demonstrated by Anna in The Third Man, and the value expressed here. Very Graham Greene. And off Maureen and Wormold walk, in one final irony, toward Big Ben. Loyalty to country? Reed likes to end his movies with uncertainty.

Fiction upon fiction and irony upon irony, this is a lovely little film. It’s not Big Art like The Third Man or Reed’s other two masterpieces, but very pleasing on its own. A film to be treasured and enjoyed.