Is this a horror movie? Fairy tale? Religious parable? A dream? All of the above and an amazing achievement given that this was Laughton’s first and only venture into directing a film. A gifted actor, he had already had immense success in both British and American films like The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933), Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), and The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939). His acting career having peaked, he and his agent Paul Gregory turned to stage, then film directing. Laughton succeeded brilliantly, bringing to movie directing a devotion to the ideal of Art: “It’s a fairy-story, really a nightmarish sort of Mother Goose tale,” he said of this movie (Callow 26). As Richard Combs has written, the film has “a pantheist sense of awe and wonder, a world where the boundaries between the natural and the unnatural, the sinister and the sublime, are fluid to say the least.” After all, a river is virtually a character in the movie.

Horror movie? Fairy tale? Religious parable? I think it’s all of the above. The way the film is built stands for all three.

first, a brief prologue, a Sunday-school lesson taken from the Sermon on the Mount;

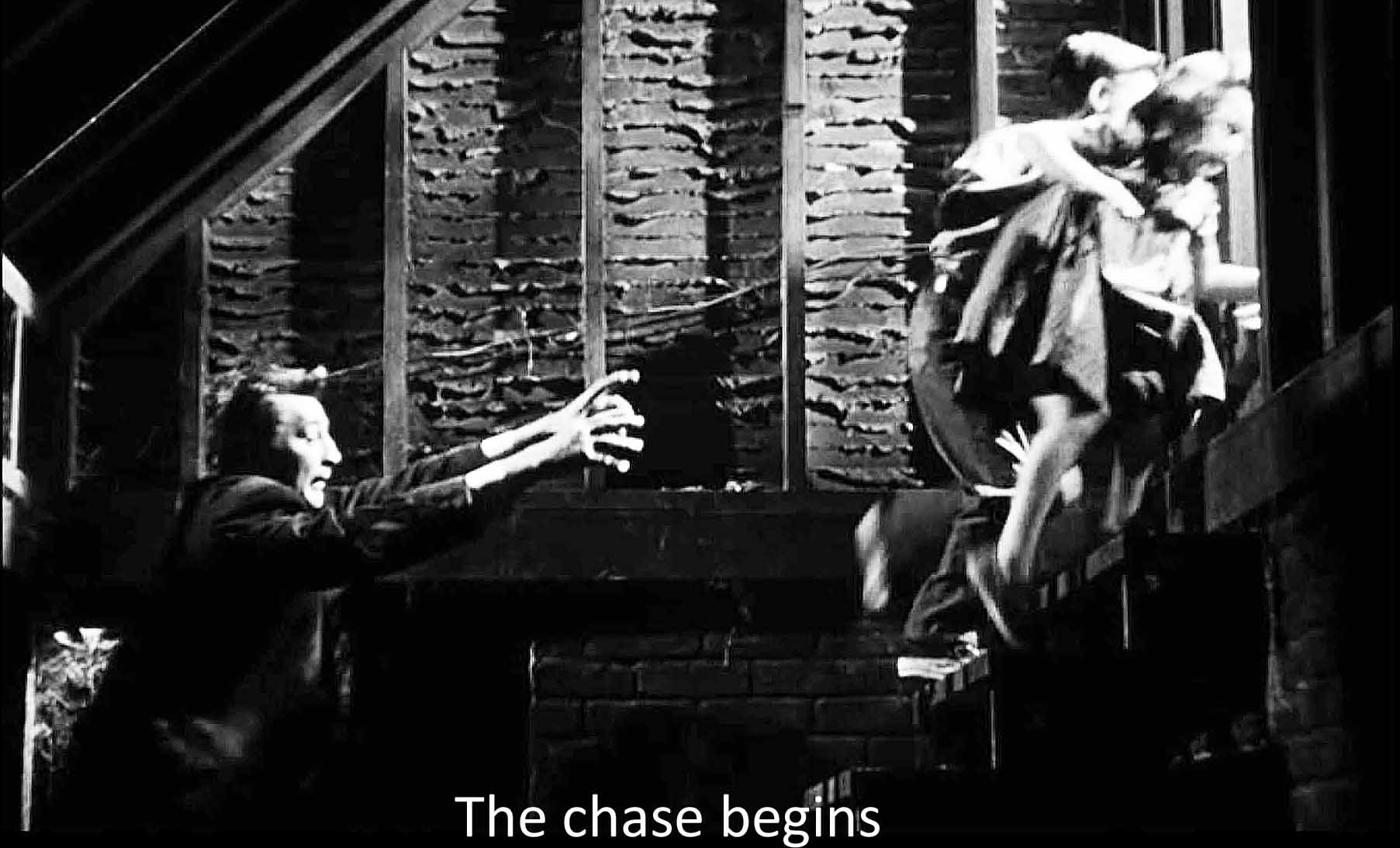

second, a long first section: a prison scene with bank-robbing Ben Harper (Peter Graves) pending hanging (no pun intended) and the efforts by his cell mate, the villainous “Preacher,” aka Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) to get the $10,000 Ben left behind, hidden with his two children ten-year-old John (Billy Chapin) and five-year-old Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce). To get the money, Preacher marries Harper’s widow Willa (Shelley Winters) and eventually kills her. Then he nearly kills the children whom Ben swore to absolute secrecy—that’s the horror movie;

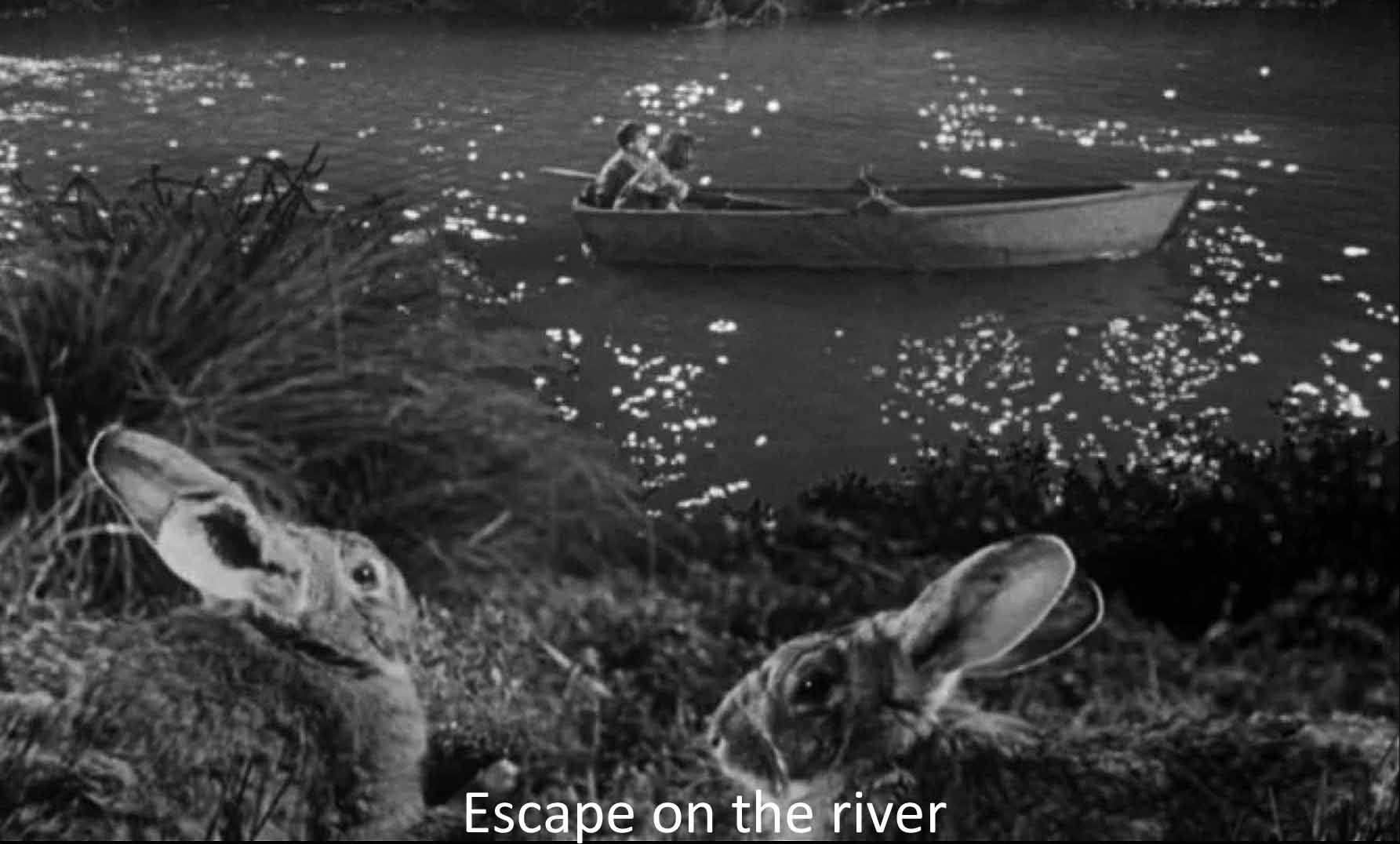

a long (12-minute) and beautiful transition, the heart of the film, in which the children escape with the money in the mythic American way by floating down a river (the Ohio)—this is the fairy tale, a kind of Apocrypha between the first section geared to the Old Testament and the final section geared to the New. As the children float by, on shore we see a spider web, a frog, an owl, a turtle, two rabbits, a caged bird, cows (notably their udders), a fox, and again and again, the stars. We are in nature, amoral but nurturing nature that lives out Rachel Cooper’s opening injunction, “Judge not lest ye be not judged.” Prey and predator co-exist neutrally, amorally. On shore humans provide Depression-deprived food (two potatoes) and shelter (straw in a barn). This is the fairy-tale;

last, an ending in which the children are scooped up by bossy but motherly Miz Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish) who has previously taken three other children under her protective wing. Her name is symbolic, “Rachel weeping for her children” (Jeremiah 31:15). She fights off the villainous Preacher, and the film ends with a loving Christmas. That’s the religious parable. If the first section dramatizes Preacher’s left hand with HATE tattooed on the knuckles, the last gives us the right hand, love. It is the religious parable.

In the prologue, Lillian Gish appears as a supernatural figure in the sky surrounded by children and stars. She is leading a Sunday School class: “Now you remember, children, how I told you last Sunday about the good Lord going up into the mountain and talking to the people.” Her preaching sets off what we will get from Preacher, and she duly warns of false prophets, using the Biblical image of a tree: “Ye shall know them by their fruits. A good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit. Neither can a corrupt tree bring forth good fruit.” Much later, in the finale, Miz Cooper will describe herself: “I'm a strong tree with branches for many birds,” the children she is sheltering. And the fruit foreshadows the apples that will be a key image in the ending. In the prologue, she reminds the children of “Judge not lest ye be judged,” that casts an ironic light on the courtroom scene soon to follow.

We cut immediately to the story’s false prophet, “Preacher,” tooling along in a stolen car, wondering whether he should kill another “widder” or not. Arrested in a burlesque show that brings out his switch blade (yes, Freud belongs here!), he is put in a cell with Ben Harper, scheduled for execution for killing two men in a bank robbery. Seeking to provide for his family, Harper netted $10,000, and we have seen him give it to his two children, swearing them to absolute secrecy. Powell fails to learn from Ben where the money is hidden. He resolves to marry his widow and get it that way.

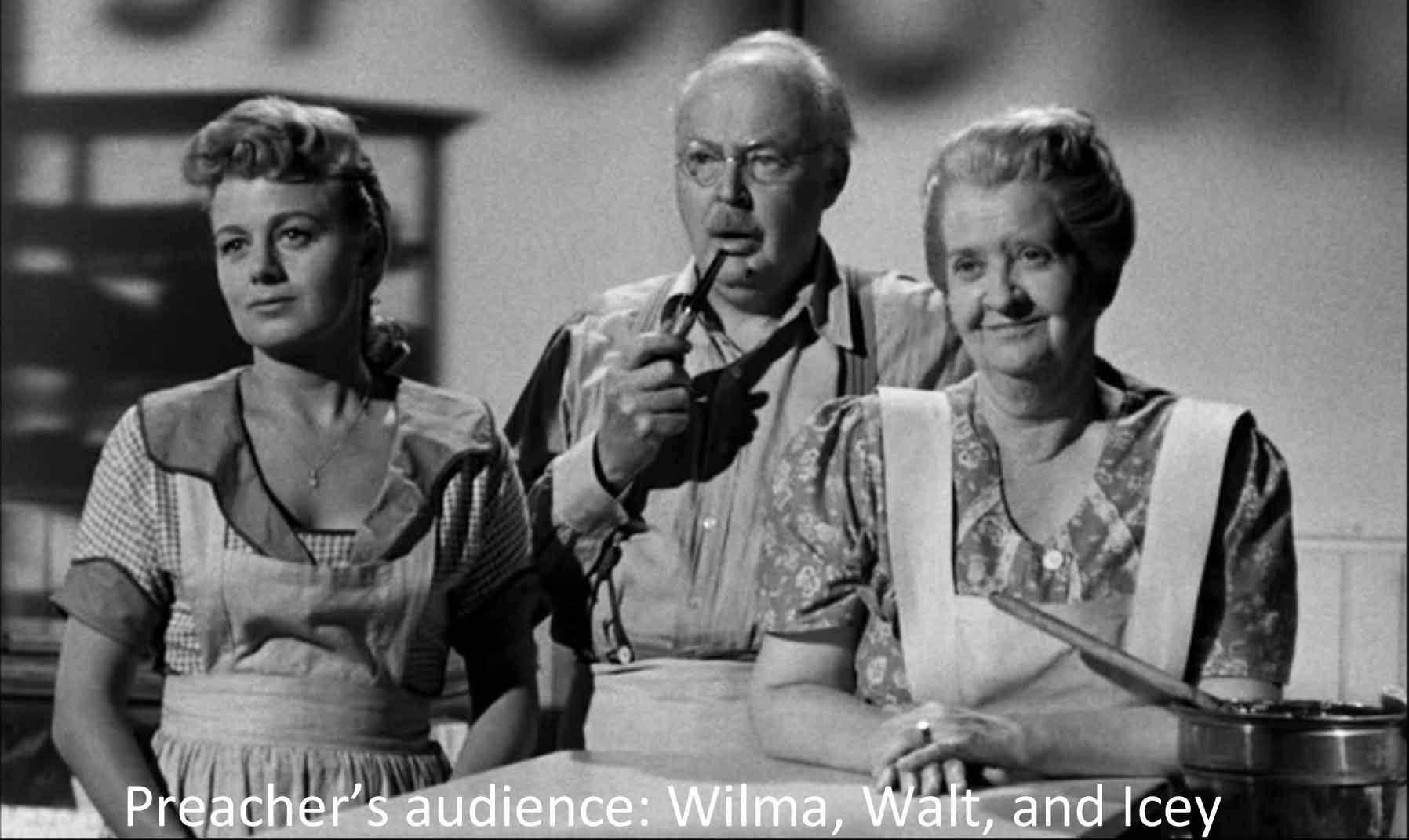

Powell charms elderly Icey and Walt Spoon, owners of the village ice cream shop (Evelyn Darden and Don Beddoe, both quite marvelous). They are Willa’s self-appointed guardians, prototypes of sexual lack, and stand-ins for all who fall for Preacher’s hate-filled brand of Christianity. In the finale, they will lead a lynch mob.

The Spoons set the tone for the other adults, all of whom fail the children. Their mother Willa Harper is taken in completely by Preacher. On their wedding night he brutally turns her gentle sexual desiring into shame. He makes her look at herself in the mirror: “You see the flesh of Eve that man since Adam has profaned. That body was meant for begetting children. It was not meant for the lust of men.” He converts her to his fanatical Calvinism, and she leads a prayer meeting, confessing that she drove Ben Harper to robbery and murder. Her reward for all this is a ritual stabbing in a strange cathedral-like bedroom.

Another adult who fails the children is Uncle Birdie (James Gleason), retired steamboat captain, widower, drinker, and John’s fishing buddy. He sees through Preacher and tells John to come to Uncle Birdie if he needs help. John does, but finds Birdie dead drunk, having been terrified by the eerie sight of Willa Harper’s body under his boat (one of the most amazing scenes in a film full of amazing scenes).

Preacher announces, “I come not with peace but with a sword,” one of Jesus’ murkier sayings, here referring to his “stick-knife.” Three times we learn its phallic nature. Once when he is at the burlesque show, when the knife pops through his clothes. Again, when he says to Pearl, "Now, don't touch my knife! That makes me mad. Very, very mad." Finally, instead of a wedding night consummation, he gives us a ritual stabbing of Willa in that cathedral of a bedroom. Preacher’s religion, “The religion the Almighty and me worked out betwixt us,” his personal brand of Calvinism, translates sex into hate.

Preacher has had H-A-T-E tattooed onto the knuckles of his left hand, L-O-V-E on the right. He dramatizes with his hands as the film as whole does, hate struggling against love, fatherly aggression and repression against motherly nurturing. Where Preacher, a man, dominated the first long section, the last belongs to the bountiful female, Miz Rachel Cooper. (And Lillian Gish makes everything that could be made of the role.) The scene when she takes the children from the river exactly matches the scene when Preacher drives them into it, with John brandishing an oar both times. Where Preacher is always talking to somebody—that is the business of psychopaths, to manipulate other humans—Miz Rachel is inclusive. Not only does she chatter to the children and the grocer and a waitress, she talks directly to us. Just as she has scooped up these children and brought them under her wing, she draws us in.

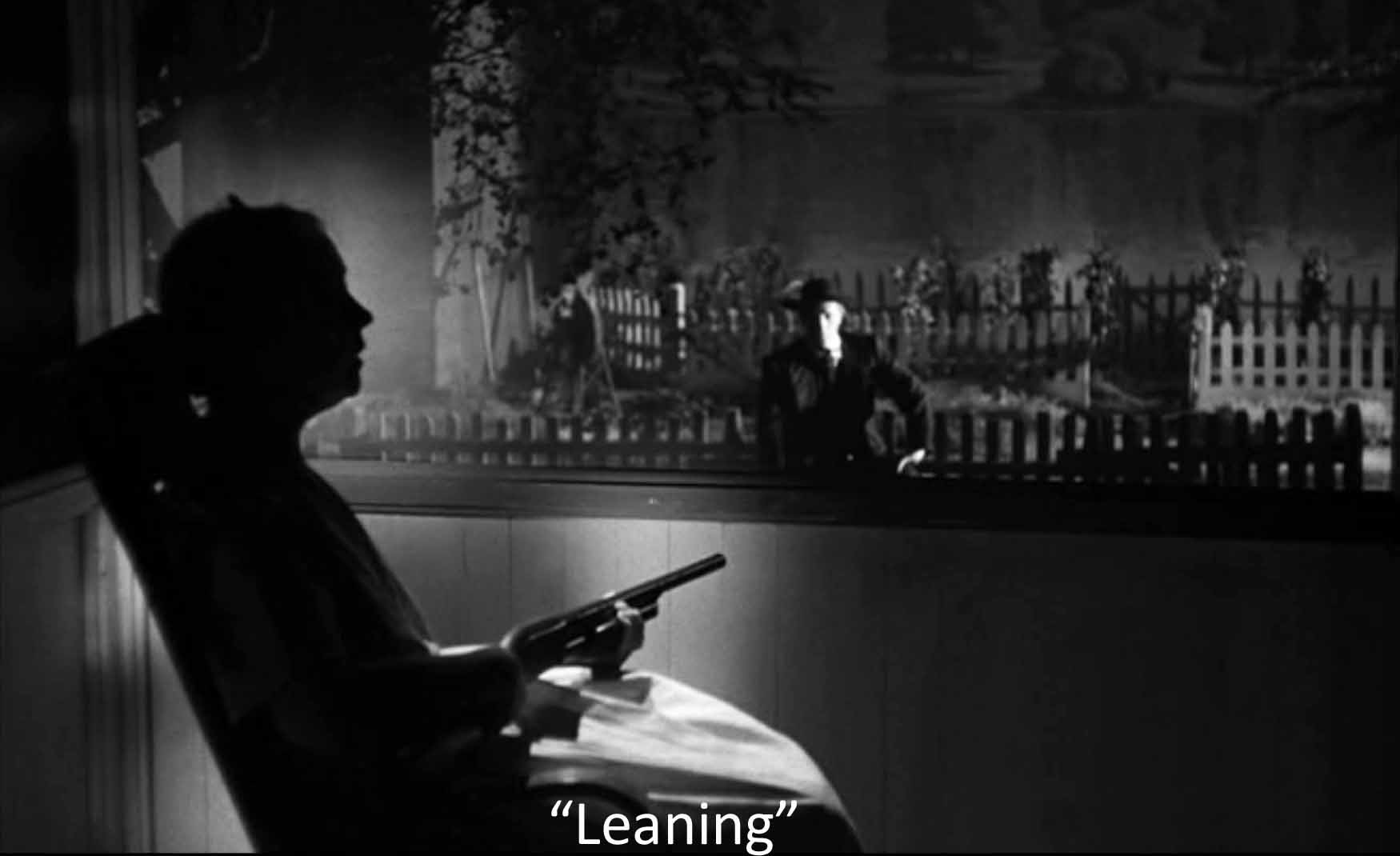

Laughton described her as a Mother Goose (and in her first scene with John and Pearl she is accompanied by geese). Other critics have called her a Fairy Godmother. I see many attributes of the Virgin Mary. Preacher sings “Leaning on the everlasting arms,” and in an exquisite moment of love and togetherness, she sings counterpoint to the hymn that he has been singing all through the hateful chase. But Rachel sings, “Leaning on Jesus,” a personage Preacher has never mentioned. Mary wears a crown of stars as Miz Cooper does in the prologue. And the Virgin is associated with a variety of trees, the palm, the olive, the plantain. Miz Cooper tells us, “I'm a strong tree with branches for many birds.” She and John exchange apples. In many paintings of Mary she or the Child holds an apple, a sign of man’s fall and the need for redemption by her son. John gives her an apple for Christmas and she calls it, “the richest gift a body could have,” our humanity.

“Ruby, I lost the love of my son—I've found it with you all.” Universal mothering, Christian agape, becomes her substitute for a lost son. Miz Cooper’s own son has deserted her and perhaps her adoptees did too, for she receives no Christmas mail: “I'm glad they didn't send me nothing! Whenever they do it's never nothing I want but something to show me how fancy and smart they've come up in the world.” So much for the end-of-year letters we inflict on our friends. But is that a joke from the anti-religious Laughton on Christ, that he has “come up in the world”? Anyway, it surely matters that the film ends with Miz Cooper, avatar of the Virgin Mary, presiding over Christmas.

As such she becomes part of the archetypal tradition of mother-goddesses and love-goddesses, Isis, Cybele, Aphrodite, Demeter, Kuan Yin, even that prehistoric statuette, the busty Venus von Willendorf. She stands for an archetypal femininity celebrated by Jung, Freud, and richly elaborated by Robert Graves in The White Goddess and other books and poems. I would say that Rachel stands for a kind of feminine principle, but she differs markedly from the other women. Icey Spoon, Willa Harper, Ruby, even little Pearl—they all fall for Harry Powell’s deceptive charm. Rachel sees through him right away (with the help of the male John). The other women find it hard to acknowledge their sexual interest in Preacher. Rachel has none, but like the mother-goddesses, Miz Cooper is richly involved in love and loving and forgiveness for amatory slip-ups, as in her comforting of her oldest adoptee Ruby.

“I’ve been bad,” Ruby confesses. (Preacher evokes her guilt about sex as he did Willa’s.) Ruby (Gloria Castilo) has been doing more than flirting with the town’s teenage layabouts. “You was looking for love, child, the only foolish way you knowed how,” says Rachel. “We all need love.” Like Willa earlier in the movie, Ruby is another fool for love. She loves a man about to be hanged (though we don’t know that yet).

Rachel also gives John a watch for Christmas The men at the beginning are "doing time." The watch signifies both mortality and masculinity: “It'll be nice to have someone around the house who can give me the right time of day.” Time is our mortality, as is the apple. Miz Cooper has given John the gift of our common humanity, very different from the gift of $10,000 his father tried to give him.

The watch leads up to the last words of the film, Miz Rachel Cooper’s, “They abide, and they endure.” The last shot is of her house, sheltering the children from the snow. The first and last shots in any film are key, and this film begins and ends with a life principle of protection and loving that will banish the deadly sex-aversion and hatred of Preacher and his Calvinism.

Charles Laughton was gay and desperately afraid of being exposed in 1950s Hollywood and America. As a result he despised the puritanical strain of Christianity that prevailed in the American Bible Belt. He ended up making a movie about Christianity, a movie that poised a Calvinist tradition of sin and damnation against—what shall I call it?—Christianity in a loving mode. Faith alone against faith plus good works.

To make such a movie, he created an extraordinary team. It began with his agent Paul Gregory who would act as producer and who had tremendous faith in "Charlie." Gregory discovered the best-selling Southern gothic novel, The Night of the Hunter, poetic, symbolic, and suspenseful. It was a best-seller. He not only secured the rights, he got author Davis Grubb's enthusiastic cooperation. Grubb sketched how scenes should look, helped rewrite the screenplay, created lullaby lyrics, and so on. Laughton and Gregory got James Agee, film critic and screenwriter for The African Queen, to write the script. Unfortunately Agee produced a script of 293 pages that would have led to a film of 293 minutes (according to the usual formula: one page of script equals one minute of film). But Agee and Laughton and Grubb working together, got it down to workable size.

By then the team had acquired the gifted Stanley Cortez as cinematographer. He began his career by working with Edward Steichen and went on to film Orson Welles' beautiful The Magnificent Ambersons and the legendary Shock Corridor by Samuel Fuller. He was able to give Laughton the alternation he wanted between high-contrast German impressionism and flat realism in the manner of D. W. Griffith and other masters from the silent era. It was Cortez who decided to use Tri-X film to get the black blacks and high contrast this horror story cum fairy tale called for. The art director was Hilyard Brown who came up with brilliant effects, such as the false perspective shot of John looking out a barn window across the river at the distant silhouette of the implacable villain. Brown was able to photograph the entire trip downriver in a sound stage. And finally, in an unusual step, Laughton had the editor Robert Golden on the set with him while filming. Laughton did not film scene by scene, slating between each. Rather, he let the camera run for the whole ten minutes of a reel, doing a scene again and again on the one piece of film. Golden made sure it would work.

Composer Walter Schumann was as important as Cortez. Schumann developed the four musical themes that, said Cortez, guided his camera work. For Miz Cooper a “Hen and Chicks” theme; for Ruby and Willa in love, a dreamy waltz (with scary variations); for Preacher, “a pagan motif consisting of clashing fifths in the lower register” (Callow 49). For the journey on the river he composed a twelve-minute tone poem interweaving two earlier songs associated with the children, the lullaby “Dream, my little ones, dream” and “Pretty Fly.” He too was constantly on Laughton’s set, for, as Simon Callow says, the music has “a controlling function.”

The budget was low, just $600,000. Even so, casting was yet another piece of luck. For the villain, Harry Powell, aka “Preacher,” the team secured Robert Mitchum who perfectly provided latent menace and insinuating sexuality. (They had asked Gary Cooper. Bad idea.) The two child actors, Billy Chapin for John and Sally Jane Bruce for Pearl) worked out splendidly. (Chapin had won an acting award the year before.) Shelley Winters played the wife Willa Harper with just the right note of vulnerability so that Preacher can flip her guilty sexual yearning into hating herself for her desires. Peter Graves ably did the small part of Ben Harper, executed shortly after the opening. The three minor characters, Icey Spoon (Evelyn Darden), the reluctant and humiliated Walt Spoon (Don Beddoe), and Uncle Birdie (James Gleason) were all right on the mark.

The great triumph in the casting came when Lillian Gish, aged 61, came out of retirement to play Rachel Cooper, the quasi-supernatural heroine. She provided the perfect link to Griffith’s style that Laughton wanted so much. It was an incredibly gifted team, able to complete shooting in 36 days. All contributed, but as Stanley Cortez said, “In the end, Laughton had the final judgment” (Callow 43).

Unfortunately, the studio suits didn’t know what to do with the picture. “Too arty,” was the verdict. In 1955, the studios had enough on their hands trying to compete with television. They were counting on 3-D and Cinemascope, and they skimped on distribution for Night of the Hunter. It flopped. Curiously, it was not until the film began appearing on late-night television that movie buffs found it, recognized it for the extraordinary work of high art it is, and proclaimed it a masterpiece and a classic. But the damage was done. Laughton, dispirited, was never able to direct again. Even so, the one film he made ranks among the greatest.