As always, pay attention to the opening. The film begins with some couples frantically jitterbugging, but alongside and behind them are their shadows and doubles out of synchronization. It's a curious image (made possible by one of Hollywood's favorite special effects techniques, the blue screen, but Lynch makes the blue screen explicit as if to say, This is going to be “only a movie.”) I also think the dual image tips us off that this is going to be another of Lynch's “two worlds” pictures (as in Lost Highway, Twin Peaks, Blue Velvet, or Elephant Man). One world will be pretty or pretty normal, the other will be black—grotesque. One will be good, one will be evil. And the existence of the dark world will make even the seemingly normal world seem unreal.

In the opening sequence, the image then shifts to a spotlit image of our heroine, Betty Elms (Naomi Watts), as a movie star receiving applause, then to red bedclothes, again, a tip-off that one of these two worlds will be a wish-fulfilling dream-world. A little later come more images of a brunette sleeping while she is hidden in bushes, then in an apartment she has sneaked into. Then an account of a scary dream by a character we see again only for an instant late in the movie. Dream, sleep, dream—we are about to see a dream, a wish-fulfilling dream.

I see Mulholland Dr. as contrasting two traditional movie stories, clichés, really. A young girl comes to L.A. and Hollywood determined to become a movie star. One story ends happily: she finds her dream, stardom, and love, and one story ends miserably: she fails at acting, is dumped by her lover, resorts to crime, and is driven to suicide out of guilt.

Given these two stories, then, Mulholland Dr. consists of four parts:

The first part (1h45min) appears to be a more or less straight story with two threads:

Perky blonde Betty Elms (Naomi Watts) comes to L.A. to become a movie star or great actress, either will do. A brunette amnesia victim, “Rita” (Laura Elena Harring), hurt in a car crash, hides in the apartment Betty has been lent. Betty succeeds in an audition, then goes into Nancy Drew mode and teams up with Rita to find out who she really is. Finally she falls in love with “Rita.”

Director Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux) suffers from cuckolding and the Mafia's overruling his choice of female lead in the movie he is directing.

There are other happenings, seemingly unconnected to these two threads.

Next comes a brief episode (10 min.) in which Betty and Rita go to the Silencio Club.

We get a new but obviously related story #3 of, now, Diane (formerly Betty, still Naomi Watts), Camilla Rhodes (formerly Rita, still Laura Elena Harring), and Adam Kesher. Story #3 is much darker than #1. And shorter: 27 min. Camilla (formerly “Rita”) has invited Diane (formerly “Betty”) to a party at Adam Kesher's house. Camilla humiliates Diane in various ways, notably by hinting at a new lesbian lover and having Dianne listen to Adam's announcement that he and Rita are getting married. Diane then pays a hit man to kill Camilla.

A very brief (8 sec.) closing shot at the Silencio Club. A blue-haired woman onstage says the one word, “Silencio.”

Throughout, there are small elements in story #1 that “leak” into story #3 where they don't belong. They tip us off that basically the two stories are two versions of one story. Words like “We don't stop here” or “This is the girl” or Adam's telling the party in story #3 about his wife's misbehavior in story #1. The opening of story #3, showing Betty/Diane asleep on red sheets rhymes both with the red sheets in the opening of story #1 and with the woman dead in apartment 17. The opening foreshadows Diane's ending.

Throughout, identities are fluid, and when we go from story #1 to story #3, characters change identities (as in Lost Highway). The “Betty” of story #1 is a name adopted from a waitress’ name tag in story #3. In story #3, “Betty” is now “Diane.” “Rita,” a name taken from a Rita Hayworth poster, is now Camilla Rhodes. In story #1, she loved “Betty.” Now she rejects her. Friendly Coco, who concierged Betty's apartment, now is Adam Kesher's mother and distinctly unfriendly. The friendly older couple whom Betty apparently met on the plane into L.A. now become avenging demons. A scary homeless man from story #1 with no connection to Betty now becomes another tormentor in story #3. There is a blue key in story #3, but it's a realistically shaped key, not the triangular prism of story #1, suggesting, I think, like these other details, that story #3 is real or realistic and #1 is not or is, at best, symbolic. But as always with Lynch, no matter how realistic the narrative looks, it is a simulation that displaces “real reality.”

And then there are the usual, as I call them, why's in a Lynch picture, mysterious characters like the Cowboy or the incompetent hit man or the woman in apartment 17 or the people at Betty's audition (with its wonderful spoof of directorial non-communication: “Don't play it for real until it becomes real”). Why are they there? I’ll put those into a different file and focus on the main puzzle.

The big puzzle that critics have been trying to solve is, What is the relation between story #1 and story #3? This is another of Lynch's “two worlds” structures (as in Lost Highway or Twin Peaks or Blue Velvet). One world is over-pretty, the other over-terrible.

There are all kinds of theories: that story #1 is Diane in the afterlife; that the two stories are parallel universes; that the two stories are new lives for the two women after bargains with the devil; that story #1 is a movie made up by the Diane/Betty of story #3; that story #1 is a schizophrenic's version of story #3, and on and on.

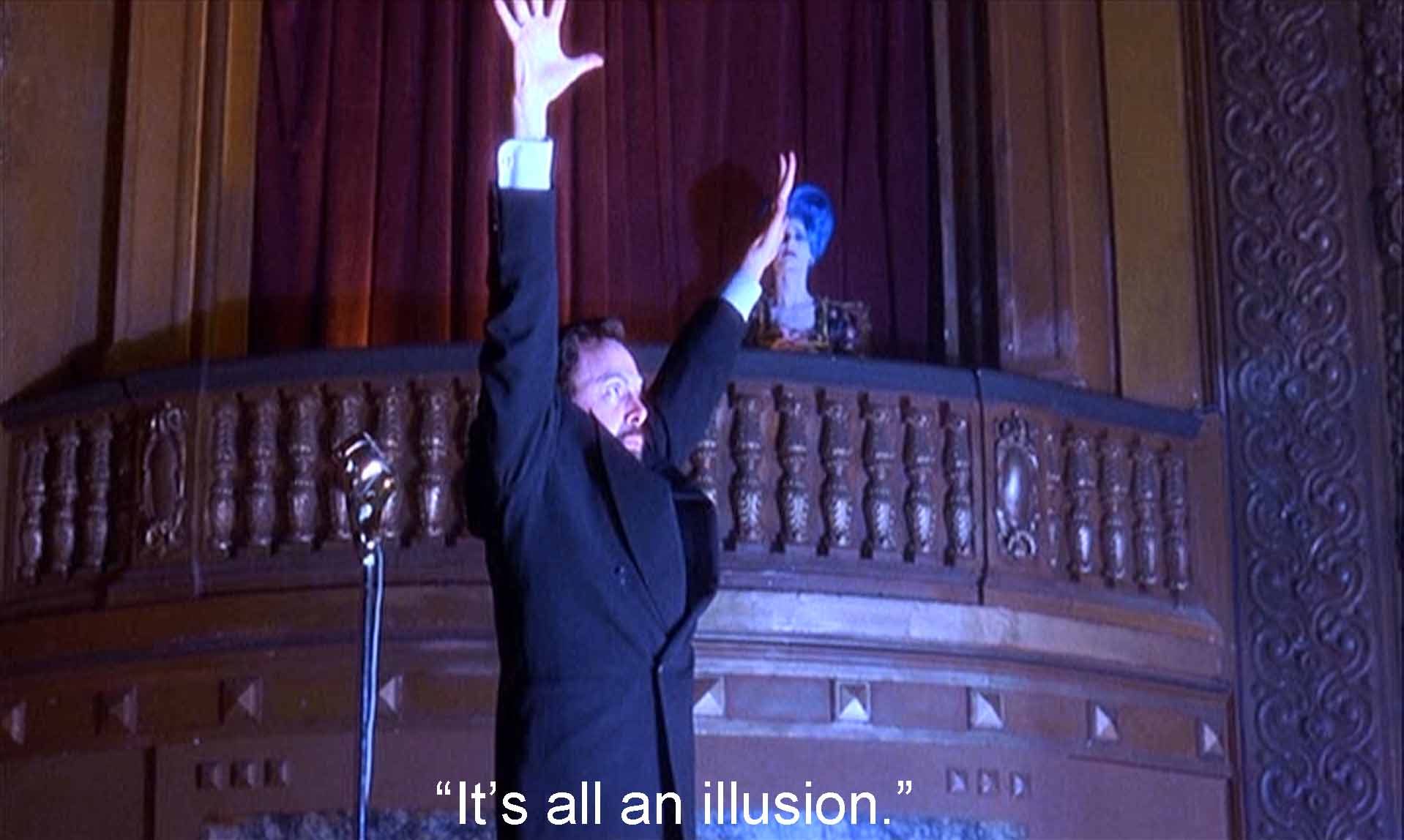

I find a key to the film in the two episodes in the eerie Silencio nightclub. The first begins with the words “No hay banda,” apparently heard by Rita in her sleep. “There is no band”—in Spanish. We hear a clarinet, then a trombone, then a trumpet with trumpeter but “No hay banda,” the MC-magician tells us. It's all a tape. It is an illusion. Why in Spanish? Because I think this is the other, the dark, hidden side of Los Angeles, shown in neither story #1 nor story #3, just as we are opening up the dark, hidden side of Betty Elms.

Then comes a song by Rebekah del Rio, “Llorando,” Roy Orbison's “Crying” (in Spanish). This is Lynch's recurring theme of “a woman in trouble.” But this too is a tape. The singer collapses, but the voice continues. It is a simulation that substitutes for reality, like this movie, like all movies. Story #1 and story #3 are equally simulations of this kind: neither represents a reality, only itself.

That, I think, is Lynch's point: that we 21st century humans live in a world of representations. Life itself has become submerged in television, movies, music, visual art. They are our reality. Our lifelong struggle, the struggle of our societies, is to control those representations, that pseudo-reality, to be to the world and to our own lives like a successful actor or director controlling the representation. Self has become split into representation and controller of the representation—like the two heroines of Mulholland Dr.

The first Silencio sequence ends with Rita finding the blue box that accepts the improbably shaped triangular key the two women had found earlier in Rita's purse. She opens the box, and the film swirls into story #3.

What is the blue box? Blue—always a significant color for Lynch, sometimes blue sky and innocence, sometimes something sexually intense and important, like a fetish (as in Blue Velvet). The box is possibly Pandora’s box, releasing the evils of story #3. Perhaps it is a Freudian box, symbol of femininity, and inserting the key a sexual act that gives birth to story #3.

Story #3 ends with a dead woman on red sheets (as in story #1). The two images again suggest to me that story #1 is a dream version of story #3. And most critics say the same: story #1 is a wish-fulfilling hallucination, fantasy, or dream version of story #3 that distorts and pretties up its grim events. I agree, and frankly, this movie would make a lot of sense if the first part were shown last, and the last part first. But that would be no fun, and who needs sense, anyway?

I’ll settle for a minimal claim that doesn't involve complicated psychology: story #1 shows Betty in a good light, as she wishes she were; story #3 shows her as a bad person, Diane, as she in fact is. But, of course, she was nothing “in fact”: as the MC in the Silencio Club says, “It's all an illusion,” which is Lynch's point.

“Silencio” is the last word of the film. Why “Silencio”? Perhaps because “The rest is silence”—Hamlet's dying words (a complicated pun), and now, indeed, the rest is silence—Diane dies and the film is over.

That last “Silencio“ is spoken by the blue-haired woman in a final brief moment in the nightclub. In the first Silencio scene, she was a spectator. Now she is the actor. I read her shift in roles as our shift in roles: we were spectators of the film, now we are in charge. It is we who must make sense of it—if we choose to. But I also hear in “Silencio,” philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein's famous statement, the closing words of his Tractatus: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” And perhaps that is good advice for the many who have tried to “solve” Mulholland Dr..

Mulholland Dr. began life as the pilot for a tv series similar in manner and complexity to Lynch's successful Twin Peaks. ABC didn't greenlight the series, but a French company stepped in with money to turn this into a film. (Lynch is a huge favorite in France.) So Lynch cut here and there and added here and there to make what might be a coherent film. Might be. I think this origin explains why there are so many subplots and appearing and disappearing characters. In the many hours of a television series, Lynch might have handled them better than in a feature-length film.

I would find it satisfying to be able to situate each detail in a coherent work of art, but I think that is asking too much of Mulholland Dr. given David Lynch's method for getting “ideas.” “I'd have coffee, sometimes six cups, along with the [milk]shake, and I'd have sugar in my coffee. By then I would be pretty jazzed up, and I'd start writing down ideas.” (Nevertheless, one Alan Shaw has made a heroic effort at doing just that: “A Multi-Layered Analysis of Mulholland Dr.” (2004), 114 pages.)

Only in The Elephant Man (1980) and perhaps the ill-fated Dune (1984) has Lynch made a conventional story-film. All his other work, I think fits into the similarly obscure style of avant-garde films after the mid-twentieth century triumphs of Antonioni, Bergman, and Fellini. I'm thinking of filmmakers like Raul Ruiz (post-60s), or Andrei Tarkovsky (post-60s), or Béla Tarr (post-#1990s). Within that company Lynch stands out for his telling use of color, his willingness to risk the screen going black and the sound fading out, his camera angles, his interest in paraphilia, his attention to the folkways of the mass media, and his willingness to abandon traditional ideas of sequence, story, character, and motivation. All these filmmakers, like Lynch, focus on representation as a substitute for a realistic reality.

The more I look at this film, the more its many details fall into place and make a coherence. But rather than try for that full explication, let’s just settle for the idea that Mulholland Dr. is bold, riveting, and incredibly imaginative. We can be grateful for it.