Enjoying: Everybody loves this film. You ought to view it and just enjoy it without my comments.

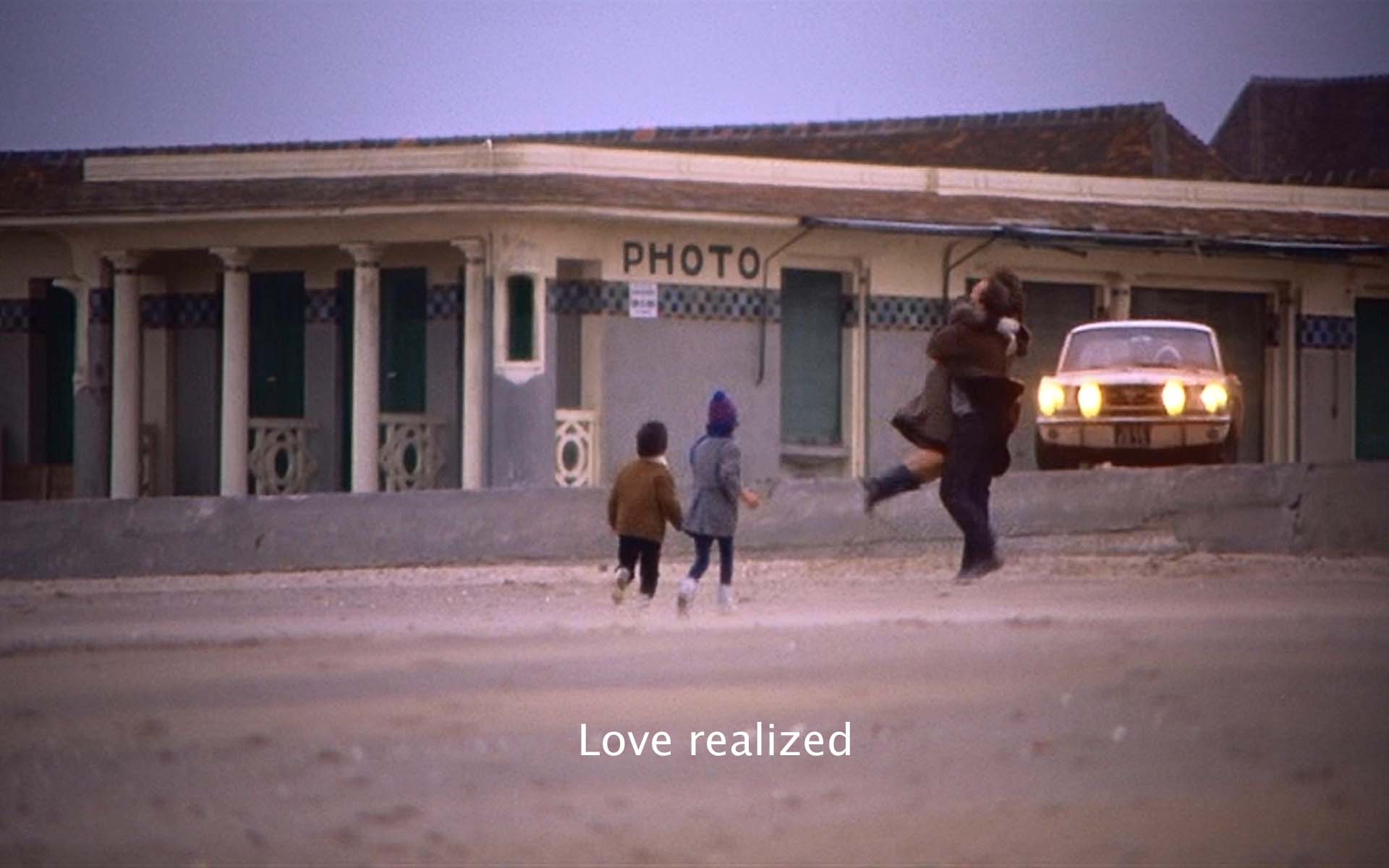

The story of A Man and a Woman is very simple. Jean-Louis (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne (Anouk Aimée) are widower and widow respectively with children parked at a boarding school in the seaside resort of Deauville. They meet when they are visiting their children. In the course of his driving her back and forth from Deauville to Paris, they reveal themselves. He is a racing driver. She works in the movies. Her husband died in an accident on set, and his wife committed suicide. Eventually Anne and Jean-Louis become intimate, but her memories of her husband intrude on the moment, and she leaves him. He races to catch her train as it arrives in Paris (or Rennes?). The film ends with their embrace.

Over and over again this film subjects its characters to the cold and wet of the summer resort of Deauville in a nasty Normandy winter. Lelouch has a character in a later movie of his describe this one as “a movie about windshield wipers.” The characters are constantly bundling up, putting on a racing costume, or nuzzling against a warm sheepskin coat. As against this cold, we have the growing warmth of the love story culminating in the scene in bed, when the lovers are anything but bundled up.

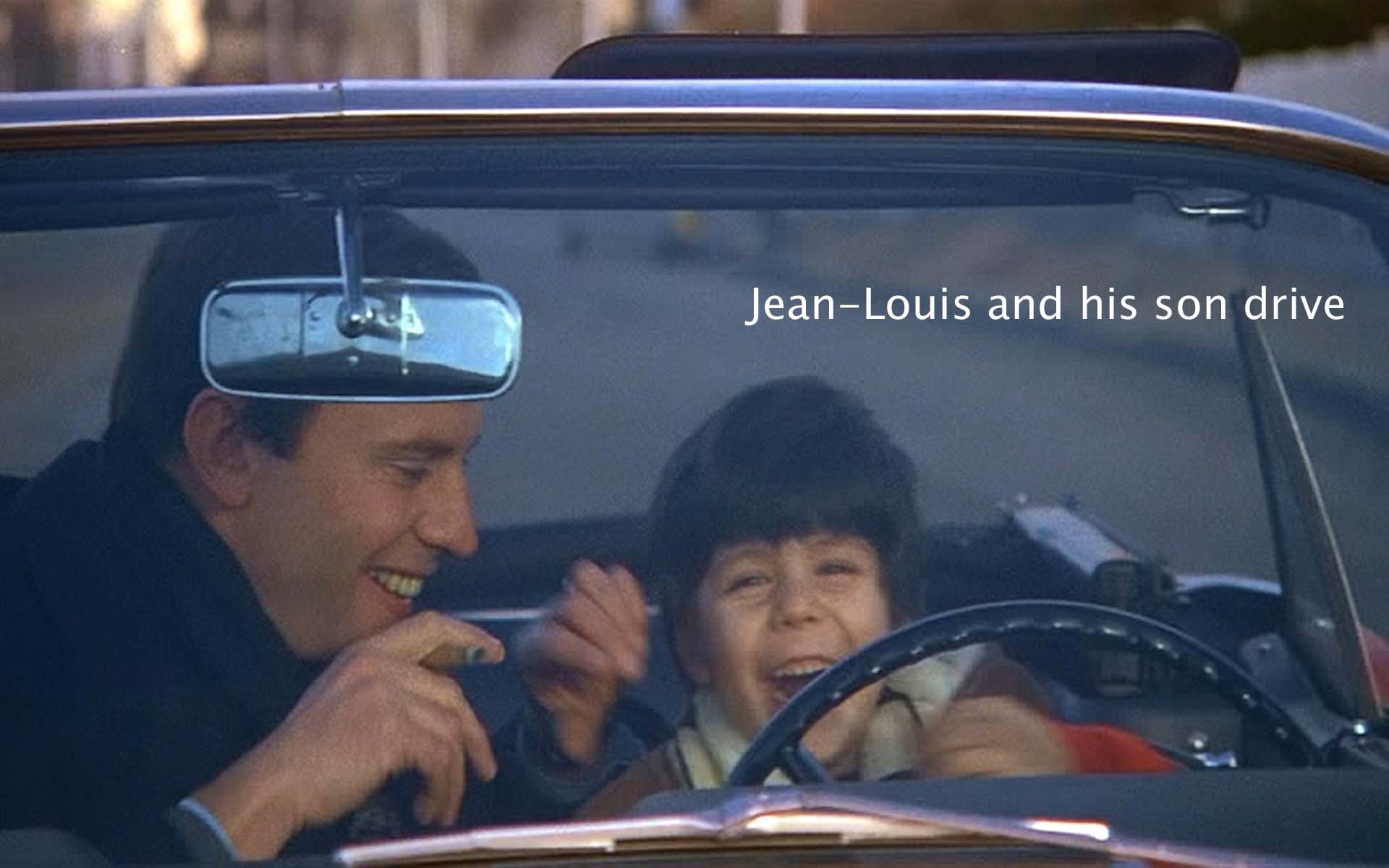

At the same time that Lelouch emphasizes the cold, he also emphasizes an intense, strong, vibrant energy. Mostly it takes the form of Jean-Louis' fiercely driving around, our hero being a racing-car driver. “Life-affirming energy,” one critic calls it. But I also understand Jean-Louis as having a particular sense of time. We start somewhere and then we race to an endpoint with great energy and force.

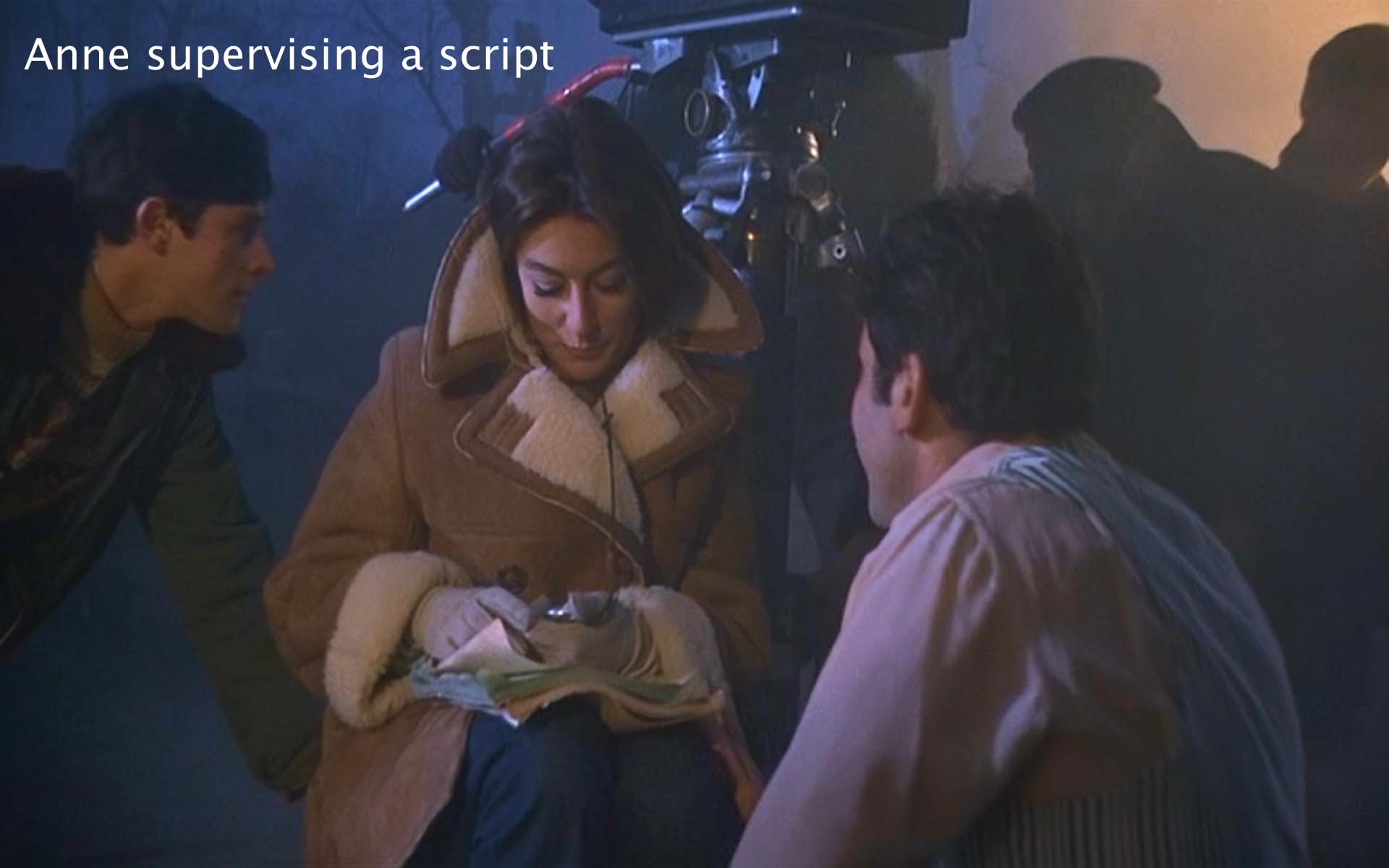

Lelouch contrasts this manly world of hard, technical realities with Anne's world of stories and fantasies. She works as what used to be called a “script girl” but is now called a “continuity supervisor.” In her job, during a movie shoot, she makes sure that what appears on the screen is consistent from one shot to the next, no matter how much the film jumps from one time period to another.

With these two worlds, the film embodies two time schemes. One speeds straightforwardly from start to finish, like an auto race. This is the overall arc of the film, but there are all kinds of flashbacks and flashforwards and fantasies (Jean-Louis as pimp, for example).

The film, as I read it, identifies its straight-line time scheme with the male in the story. He goes from meeting this attractive woman to becoming more and more interested in her and finally going to bed with her and beginning what he hopes will be a full-fledged relationship.

The other scheme jumps around in time and space, like the time scheme of a movie. It is really psychological time. This movie-psychological time mostly happens inside Anne's mind. In this psychological, story-time, she opens the film by telling the finale of Little Red Riding Hood. When she recalls her stuntman husband, she gives us a Western, a bunch of car crashes, a vampire(?) movie, and finally the war movie in which her husband dies. “Your story is like a soap opera,” says Jean-Louis. But in her relationship with Jean-Louis, this psychological time, her memory of her husband, intrudes on their love-making scene in the manner of a movie cutaway. (It is, of course, literally a cutaway.) And that ends the relationship, at least temporarily.

The contrast between these two time schemes seems to me the core of the movie. In a documentary about the making of this film (recorded on the DVD), Lelouch commented: “We do not tell the story in a logical way. It is the couple's sense of time. We make constant incursions into the past and future of the characters. We keep the past constantly in mind in order to know what the present and the future will bring.” He too was, apparently, thinking in terms of time.

As for me, I identify these two time-schemes with the reality of the racing industry where people really die and with the fantasy world of stories and movies. I identify the two schemes also with the Man and the Woman of the title. I suppose I will lose my feminist credentials for suggesting this, but isn't this straight-line, no-nonsense, start-to-finish forcefulness prototypically male? And isn't the circuitous, interrupted, wandering kind of time line prototypically female? I had probably best leave the answer to the Jungians and the Freudians and the other psychologists. But at least such a reading would justify the title of the film: A (prototypical) Man and a (prototypical) Woman.

Lelouch made this film in the heyday of the French New Wave. He used the same bewildering techniques developed most notably by Jean-Luc Godard in Breathless (1960), but practiced by all the New Wave directors, Truffaut, Resnais, Chabrol, Malle, and the rest. Bewilderment was the order of the day. (I labeled their work back then “The Puzzling Movies.”) And Lelouch dutifully bewilders us with jumbled time schemes, shifting from color to black and white and back again, an inconclusive ending, and so on.

Nevertheless, the film was a huge critical and commercial success. It received two Academy Awards, for Best Foreign Film and for Best Original Screenplay. It got the Grand Prix at Cannes. And it got an award from the International Catholic Office of Cinema—for reasons best known to the clergy. Ultimately, critics have said, it became the ultimate date-movie of the mid-1960s. People love A Man and a Woman, and I am sure you will, too.

But, alas, I have had a lot of trouble with this movie. I can come up with only two ideas for you, the two time schemes and male-female. As an old New Yorker, I would call this movie schmaltzy. The excellent critic, David Thomson calls Lelouch, “slick, meretricious, and high-minded.” His work “manages to be profitable by smothering the prickly realities of people and by insinuating the style of advertising into fiction.” Lelouch, he says, “works like a still photographer for a glossy magazine.” “Lelouch persistently films in telephoto: this leads to soulful close-ups of people cut off from their environment. The background is unnaturally flat, foreground detail is out of focus. There is an accumulating claustrophobic sterility in his films because the characters have no three-dimensional existence. They live only in the mind's maudlin telephoto, forever gazing sadly at their factitious predicament.” “Lelouch's style proclaims a callow hack.”

Whew! As for me, I share Thomson's feeling that the people are too pretty and the story too sentimental, and the children are too adorable, and I can't stand that damned dabba-dabba-dah, dabba-dabba-dah music. But I'm reluctant to pass that kind of value judgment unless I can fully understand what I am watching. And, frankly, I don't understand this movie. It leaves me with a host of questions that I cannot answer.

And so on.