Laura Hunt is dead, blasted by a shotgun. (Über-beautiful, buck-toothed Gene Tierney, once one of young JFK’s girlfriends, played Laura.) Detective Mark McPherson (rough, tough Dana Andrews) is out to find her murderer. Dana Andrews was in five Preminger films, Gene Tierney in four.

In the opening shots of the movie, McPherson ambles disapprovingly around the apartment of her great friend, Waldo Lydecker, a widely-read columnist. Clifton Webb plays the acidic columnist, who writes with “a goose quill dipped in venom.” His brilliant performance should have made his career—and happily, it did.

For the first half of the movie, we learn Laura’s story in lengthy flashbacks monologued over by Lydecker. Trying to make her way in an advertising agency, she interrupted his lunch to solicit a product endorsement (appropriately enough, for a pen). He rudely refused, then repented his rudeness, came to her office, apologized publicly, gave her the endorsement, dated her, and boosted her career to the point where she now heads her own agency and has become a figure in the swankiest circles of New York. Now she wants to marry shady but handsome social climber Shelby Carpenter (Vincent Price). To break up that romance, Waldo tells her of his various misdeeds and infidelities. She goes away for the weekend to think things over. And then her shotgunned body is found. Laura is dead.

All this we learn in long, long flashbacks. McPherson settles in for the night at her apartment to think things through. In one of the especially admired scenes in this movie (full of director Otto Preminger’s long takes) he prowls around as he had done at the opening in Lydecker’s apartment. He stares at her portrait, looks at her diary, handles the dainty items in her bureau, reads her diary, drinks her whisky—and falls asleep. Suddenly there is Laura! She wasn’t dead after all. The dead girl was a model in her agency that Shelby had been dating.

McPherson continues to pursue clues, and, in the best film noir tradition, he confronts all the suspects gathered together. Finally, even though he has fallen in love with her, he takes Laura to the police station where he brutally accuses her of murdering her rival. And there she accepts his love. Warning! Spoilers after this point.

Laura somehow made it through false starts (changes in director and stars) and the meddlings of executives to become the great favorite it has always been. This movie, like Casablanca, only happened because of some lucky Hollywood accidents. Even so, I have trouble with this film. The women’s clothes—those hats! those padded shoulders!—seem ugly. How could any woman fall for weak, oily, corrupt Shelby Carpenter? Laura’s haughty aunt Ann (the great classical actress Judith Anderson) talks in the formulas reserved for the rich Other Woman. And she is too old even for Shelby. Often, Shelby’s, Ann’s, and McPherson’s lines seem trite and unconvincing (to me, at any rate). What redeems the dialogue is Lydecker’s wit.

The story is riddled with flaws. The narrator is a dead man (the Sunset Boulevard tactic). Mcpherson behaves as no detective would, taking first one, then two suspects along while he questions other suspects. He leaves the murder weapon overnight in a potential victim’s apartment. Yet despite all this, the film was a hit and remains one of the movies people most remember from the film noir of the ’40s. I think that may be because it retells one of the enduring classical myths.

As you watch the scenes of the movie, you may begin to notice again and again what the French would call objets d’art in the background: paintings, small sculptures, vases, a special baroque clock. The first and last shots both show objets d'art. The clock is particularly important: it appears in both the opening and closing scenes and off and on throughout. Finally, its face is smashed like the face of the murdered woman. The over-decorated rooms crowd every image with objects to look at and admire. The completely bare room at the police station makes a stunning contrast. Things, things, things, and the high priest of things is Waldo Lydecker.

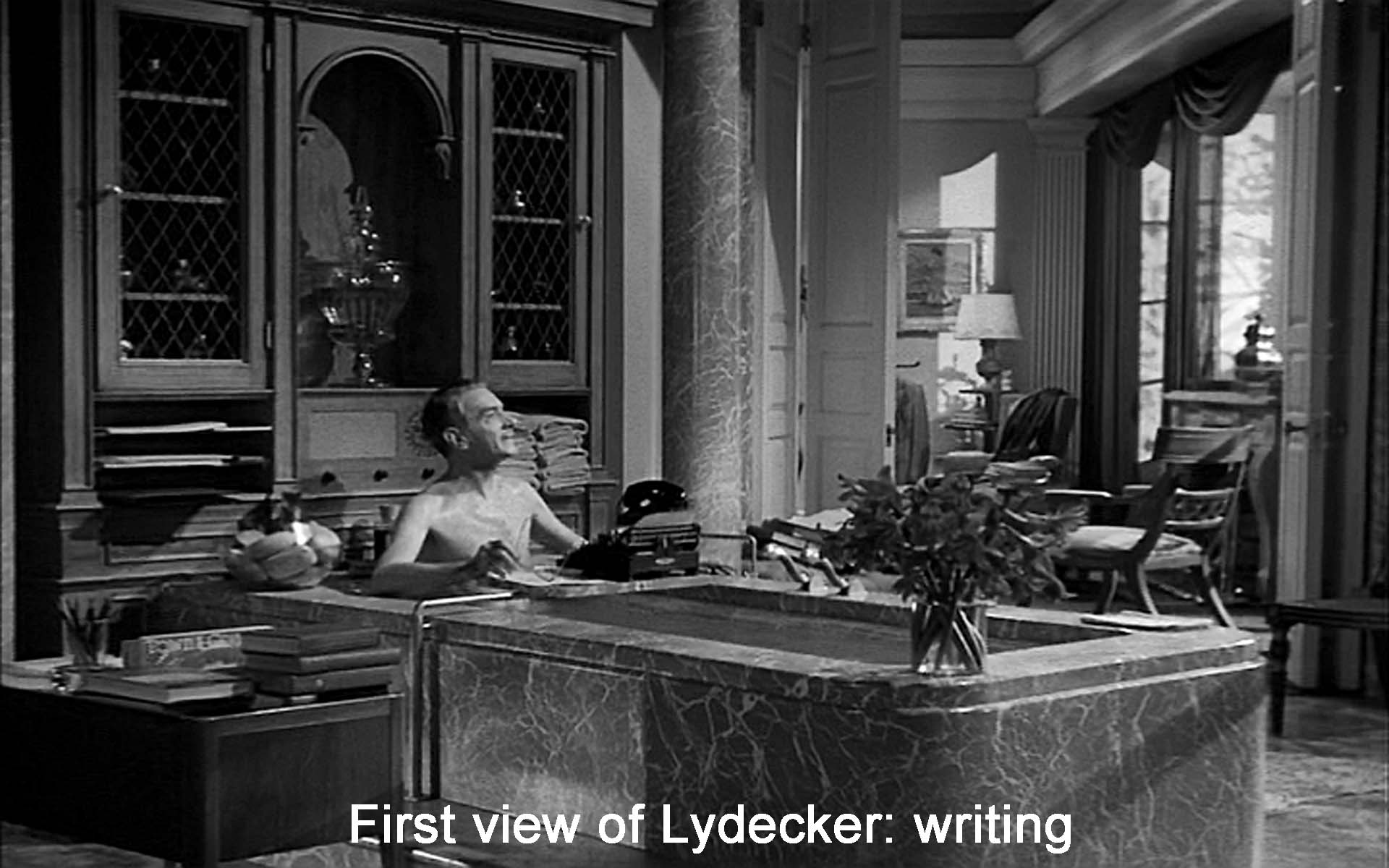

Lydecker is a critic and columnist, the toast of New York. He writes about works of art and incidentally people, judging them like a critic. (The four scriptwriters modeled him after the New Yorker columnists and Algonquin wits of the 1940s, in particular, Alexander Woollcott—see The Man Who Came to Dinner, 1942). The first shot of the movie shows us detective McPherson skeptically inspecting the art works in Lydecker’s apartment, including the baroque grandfather clock that will be crucial to the plot. Within the movie Lydecker creates Laura for us in his long recounting of their meeting, their relationship, and her turning to other lovers notably the smarmy golddigger Shelby Carpenter (Vincent Price). Indeed Laura in this picture is the famous portrait (actually an enlargement of a photograph, painted-over to look like an oil). As Tierney herself said, expressing her doubts about the role, “Who wants to play a painting?” And she is the famous melody composed by David Raksin that became a popular song (#1 on the Hit Parade of those days). Laura is works of art.

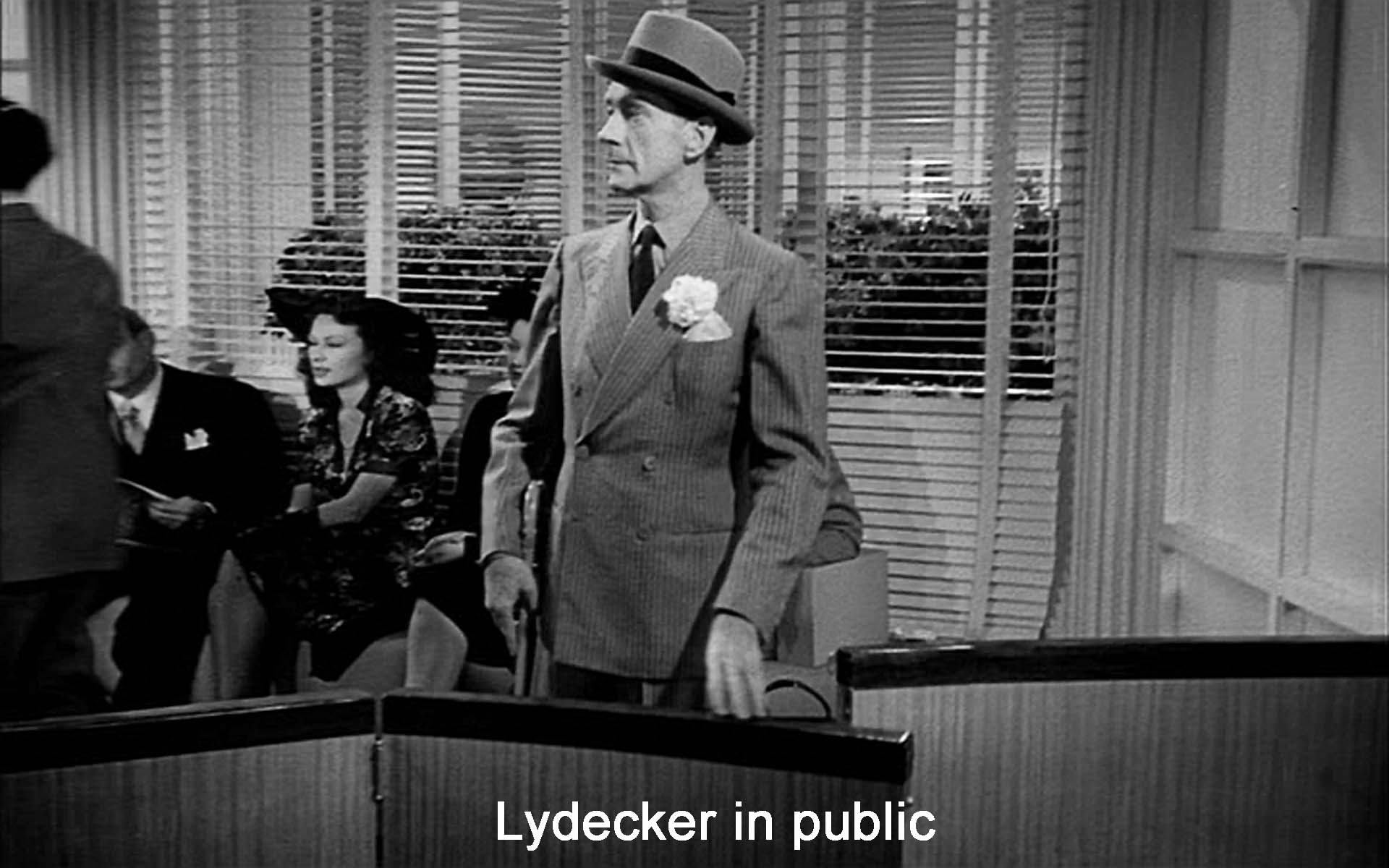

We tend to forget that the whole movie, from beginning to end, purports to be told in voiceover by Lydecker. Lydecker creates Laura. He also creates himself. An arrogant poseur and a stager of the witty put-down, he presents himself to the world as a work of art. He covers his skinny body with the smartest British tailoring, adorned with a boutonnière and a carefully fluted handkerchief. (Even when he collapses near the end of the picture and has to stretch out gasping on a couch, the next time we see him, he has put himself together in this elegant fashion.) And Laura is part of the Lydecker picture: “She became as well-known as Waldo Lydecker’s walking stick and his white carnation,” he tells McPherson.

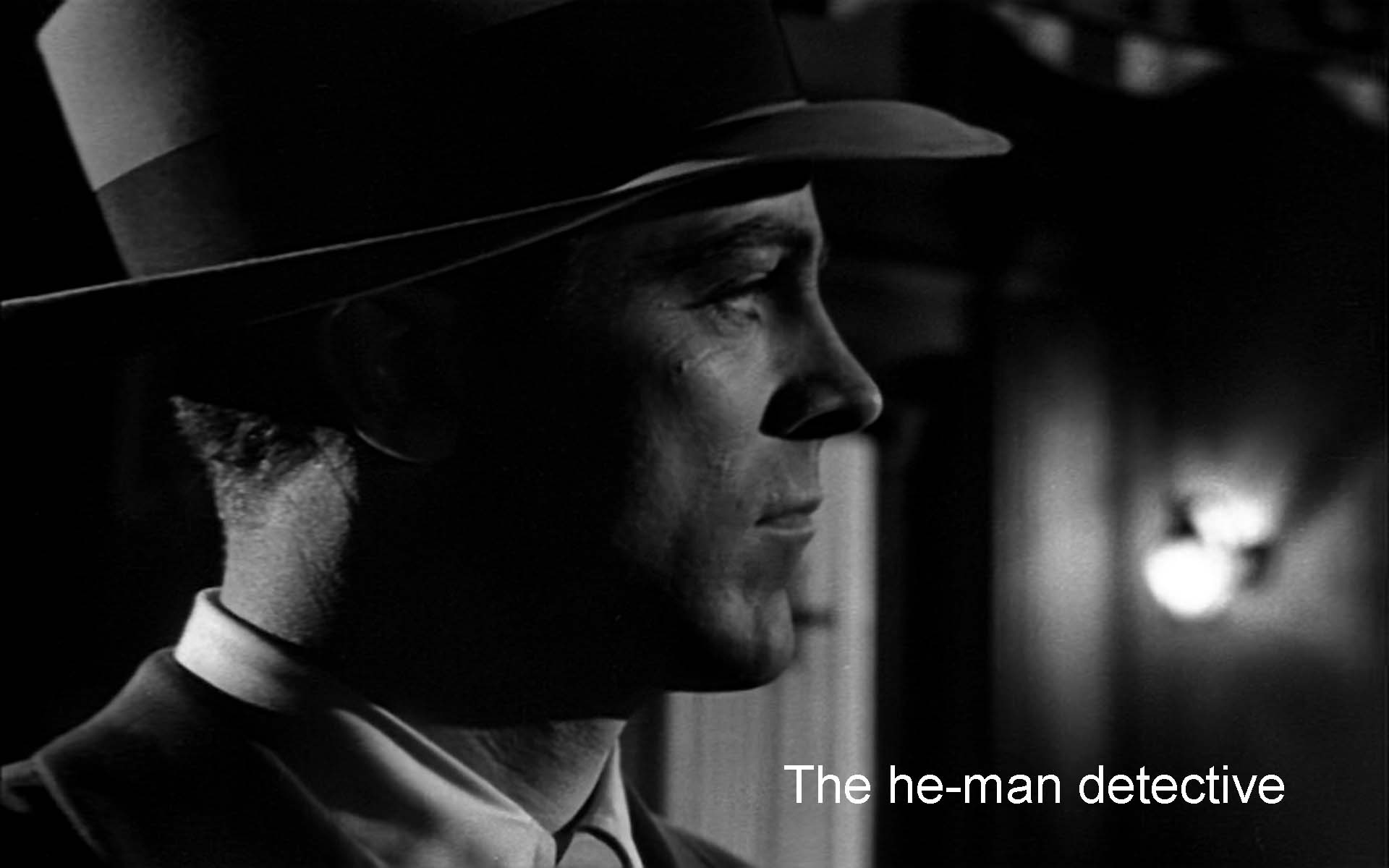

By contrast, McPherson himself is your square-jawed, big-shouldered, no-nonsense All-American Guy, complete with an interest in baseball. He distrusts women. He treats ‘em rough. He calls women “dames” and “dolls,” and he, of course, is the one who wins her heart. When did Hollywood ever not value rugged ignorance over skinny intelligence? (Waldo doesn’t trust her either, though, a reflection of classic Hollywood’s eternal doubts about Woman.)

In creating Laura, Leydecker becomes Pygmalion, the sculptor-creator of classical myth. A worshipper of Venus (beauty), Pygmalion sculpted a Galatea so beautiful and wonderful that he himself fell in love with her. Venus graciously gave the statue life. (Ovid gives a pleasantly erotic account, and the best version of the story is, of course, Shaw’s play.) Laura is Lydecker’s creation—a beautiful objet d’art. The thought of another man’s handling her drives him crazy.

McPherson falls in love with Laura through her things: the decor of her apartment, her diary, the contents of her bureau, her perfume, her whisky, but, above all, her portrait. (And the Laura theme plays as he does so.) A couple of times McPherson smirks when Laura denies loving other men, a tip-off to his attraction. But unlike Lydecker, McPherson, the detective, no critic or artist, can lust after and perhaps love the woman as woman. Artist Lydecker sculpted her as a work of art, a possession, not another human being. McPherson acts out our role—he is the audience, the non-professional participant in the experience of beauty. The little put-the-balls-in-the-holes pocket game that he plays neatly symbolizes his relation to objets d’art. The little balls are his version of people-as-things. People are tiny, easily manipulated, not to be revered. The box echoes the frame around Laura’s portrait. He does not worship works of art that make people into figurines or paintings as Lydecker does. Things are small to him, to be used and experienced, not just admired. That is why he can be the right man for Laura. Key is the love scene in the bare room at the police station in which he accuses her of the killing. She has to be more than just a beautiful object. She has to be a human being with a conscience.

One can read the final falling-in-love more darkly, though. McPherson rather brutally pulls Galatea down from her Galatean pedestal. He treats her with suspicion. When she phones after he has told her not to, “Dames are always pulling a switch on you,” he wryly remarks. Ultimately, he accuses her of the murder in front of her friends. He bullies her in the scene in the police station. Leydecker creates Laura and idealizes what he has created: “The best part of myself—that’s what you are.” By contrast, McPherson treats her as a desirable woman. a woman to be bullied and cut down to size. Then he can fall for her, and, as he says, “It was getting so I felt I needed official surroundings.” Dana Andrews, with his thin-lipped mouth and jaw clenched, wears a perpetual sneer that fits this attitude to a T.

The movie, then, acts out Pygmalion, but with a twist. It splits Galatea’s lover into two men. One is the sculptor-creator. The other is the lover-enjoyer. One treats Laura as a possession he has created. The other treats her as a sex object to be lusted after and dominated. Read that way, the film gives us two unsatisfactory ways of relating to Woman: idealizing her or making her just a sexual object. Indeed, Laura gives us not just these but two other variations on How to Treat a Woman. Golddigging Shelby and hoity-toity Ann also treat people as things. “I can afford him,” Ann says of Shelby. Shelby treats Laura as someone whom you can get things from, a kind of golden goose. Her friend Ann treats her, as one woman might treat another, as a rival. By contrast, the humble, lower-class maid Bessie (Dorothy Adams) can love Laura for herself and treat her as a real live person. Laura is a film about obsession, yes, but also about all the ways we relate to our fellow human beings as things and as people.

Of the four relationships, it is Lydecker’s that shapes the movie. But his relationship isn’t love or even sex. He doesn’t desire Laura except as a possession or an aspect of himself. His walking stick, with which he threatens an office boy, is an aggressive phallic symbol with which he compensates for his impotence. In the real world, a protogée like Laura would be Leydecker’s mistress, and the rivals he destroys would be her lovers, but this was 1944. You couldn’t say that under the Production Code. Hence he has to look asexual, and does. Or homosexual, and you couldn’t say that in 1944, either. A lot of critics have said it, though.

They see Leydecker, not as impotent or a sexual zero, but gay. Lydecker fits the stereotypes: he is effete, a dandy, an aesthete, a social gadabout, a wit, and not attracted to gorgeous Laura. In the film, McPherson smirks as he glances below nude Waldo’s waist in the bathtub scene. Indeed, to Roger Ebert’s eye, “The only way to make [the Waldo-Shelby-Laura love triangle] psychologically sound, would be to change Laura into a boy.”

Sexuality aside, this movie is asking, What is a human and what is a thing? What is living and what is dead? That’s the great mystery in this film of mysteries. Laura is dead and comes back to life. Leydecker comes back to life to narrate the film, apparently from a tape for his radio column. Waldo ends this radio program by saying, “Love is stronger than life. It reaches beyond the dark shadow of death.” The line is doubly true, for it comes from a man who has resolved to die with his love, he himself becoming some kind of ultimate work of art, namely, the movie Laura. After all, that is what movies do—make people into things.