The film opens with shots of the Corleones’ abandoned Lake Tahoe compound (and a flashback to the killing of Fredo ordered by Michael which colors this whole film). Michael (Al Pacino) is now sixty and preoccupied with making the “family” legal, legitimate, and respected. Michael invites his now-grown children, Anthony and Mary, to a ceremony in which Archbishop Gilday (Donal Donnelly) ennobles Michael as a Commander of the (perhaps fictitious) papal knightly Order of Saint Sebastian. (He is perhaps influenced by a $100 million donation to the Church from the Corleone Foundation.) There follows a big party at which we meet Mary his daughter (Sofia Coppola) and Anthony his son (Franc D’Ambrosio). They had been brought up (for safety) by their mother Kay (Diane Keaton) whom Michael had cruelly kicked out in Part II. They all turn up at the party as does Michael’s sister Connie (Talia Shire) and his brother Sonny's illegitimate son, brash Vincent (Andy Garcia).

Son Anthony wants to be a singer, not a mob lawyer. Kay backs him, and Michael reluctantly agrees. Vincent has inherited his father’s explosive temper and is quarreling with his boss, Joey Zasa (Joe Mantegna). Zasa has been entrusted with the Corleone businesses in Little Italy, but is mismanaging them. Michael takes Vincent under his wing so that he can learn from him as Michael himself had learned from his father. But meanwhile Vincent has begun a relationship with Mary who loves him.

Michael heads off to Rome where he engages in some complicated financial shenanigans. He provides $600 million to bail out the Vatican Bank (that Archbishop Gilday has mismanaged and plundered). In exchange, Michael wants a controlling interest in Immobiliare, a huge real estate holding company controlled by the Vatican. But Pope Paul VI dies before he can ratify the deal.

An aged Don Altobello (Eli Wallach), professing deep friendship and concern for Michael, tells him that his fellow mafia chieftains want in on the Immobiliare deal. At a big meeting of “the Commission” (all the heads of “families”) Michael pays them off, hoping to end his relationship with them and his participation in the gambling that has enriched them all. (Coppola plays down the mafia’s more brutal activities.) He gives Zasa nothing, and Zasa responds with the “helicopter hit,” shooting through the roof to mow down the various dons. Vincent gets Michael out. But, “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.”

Zasa has thwarted his effort to become legitimate. Back home, though, before he can avenge the attack, Michael suffers a stroke. While he is hospitalized, his sister Connie takes over. (She has evolved into a kind of Wicked Witch character because of her devotion to Vincent.) She gives Vincent the order to kill Zasa. Cleverly disguised as a mounted policeman, he succeeds—another killing at a religious festival.. Michael is furious and reasserts his authority.

Now the family plans to attend son Anthony’s debut as an opera singer at the Teatro Massimo in Palermo. In Rome, however, various crooked schemers in the Vatican’s higher circles block Michael’s Immobiliare deal. “All my life I kept trying to go up in society where everything higher up was legal, straight, but the higher I go, the more crooked it becomes.” Looking for help Michael meets with Cardinal Lamberto (Raf Vallone), a “true priest.” Impressed by his sincerity, Michael tearfully confesses his many sins, the worst being the killing of his brother Fredo. But he cannot repent; he has to go on.

The family comes together in Sicily for son Anthony’s debut as the lead in Cavelleria Rusticana.. (The opera builds on the same rigid code of revenge that Michael is locked into.) Michael and Kay tour the ancestral town of Corleone, and he asks her forgiveness. They acknowledge their love, but she does not reunite with him. Meanwhile Vincent has been spying and now tells Michael who is behind the Vatican machinations. Michael makes him the new Don, and Vincent agrees to give up Mary, making her furious at her father. Pope Paul VI having died, Cardinal Lamberto is elected John Paul I who immediately sets about cleaning up the Vatican’s financial mess. That, of course, will never do.

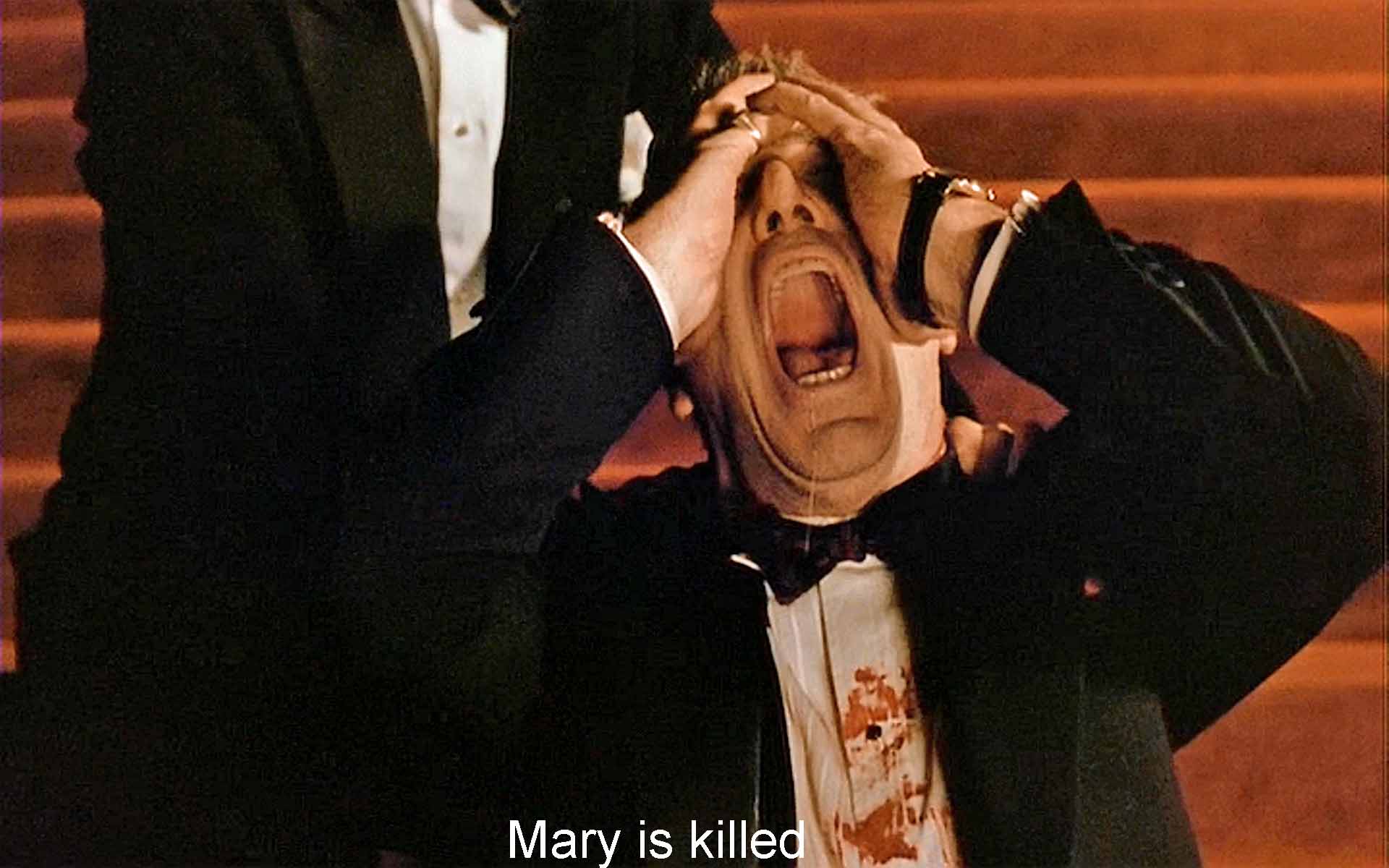

Anthony’s debut is-surprise! surprise!-a great success. Cross-cut with scenes from the opera, other scenes show Vincent and Michael’s killers murdering the Vatican plotters, but not before they have poisoned the new pope. And Don Altobello’s assassin follows the family exiting the theater, wounds Michael, but kills Mary. Michael screams in agonized grief. We get a montage of the three women whose attachment to him has hurt or killed them: Mary, Apollonia (from the first Godfather), and Kay.

The last shot shows an old Michael, broken in spirit, sitting in a chair in front of his Sicilian villa. He drops an orange, slumps, collapses, and dies, totally alone except for a small stray dog (who echoes an early conversation in which those who disrespect Michael are considered dogs and perhaps also the cat at the opening of the trilogy). By contrast, Vincent’s story is a kind of Horatio Alger fantasy. The poor boy rescues the rich man who adopts him, and then he succeeds to the rich man's business.

Yes, it’s a terribly intricate plot, and that’s one of the criticisms reviewers made of the movie-too complicated. But isn’t that the job of a reviewer, to sum up the plot no matter how involved? Anyway, the film came in for a lot of adverse comment compared to the previous two Godfathers.

Shot and released fifteen years after The Godfather, Part II, Part III’s delayed appearance hints at a variety of difficulties. Coppola himself regarded the series as finished with Part II and was reluctant to do a third, but Paramount used his financial difficulties from a couple of flops to twist his arm. He has said he regards Part III not as part of the series but an epilogue. There were casting problems. Julia Roberts, Madonna, and Winona Ryder all did not take the part of Mary, Michael’s daughter. Eventually, Coppola gave his daughter Sofia the role. Reviewers have said a lot of unkind things about Sofia Coppola’s acting; I’ll not add to them.

To play the lawyer-consiglieri of the Corleone “business,” Coppola had wanted to get Robert Duvall again. Then Michael could end the series with all three of his brothers dead. But Duvall demanded pay equal to Pacino’s, and Paramount wouldn't come up with it. That led to another less than happy choice, George Hamilton to replace Duvall. Hamilton has a slick, confident, Ivy League manner while Duvall had a worried, subservient look that I thought made the character much more appealing.

Interestingly, as a mark of Michael’s new respectability, everybody now pronounces Corleone with a silent e at the end. In the earlier pictures only the anglos did. Now even the Italian-Americans do.

In Part III, there are all kinds of echoes and continuations of small pieces from the two earlier Godfathers. Coppola continues his use of a particular “incidental imagery,” oranges, fish, and big, black cars. Crooner Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) repeats his singing a love song to Connie from the first Godfather. The drawing of a chauffeur-driven limousine that Anthony made as a little boy in Part II turns up here. Michael’s children refer to “bad memories,” the assassination attempt in Part II. And, of course, Michael’s having ordered the killing of his brother Fredo casts a shadow all through Part III. Then there are parallels. Don Altobello (Eli Wallach) copies the aging, treacherous partner Hyman Roth in Part II, and the killing of Joey Zasa during a religious parade echoes the killing of Don Fanucci. Michael’s stroke incapacitates him as Vito was incapacitated in the first Godfather, and his resigning as head of the “family” corresponds to Vito’s resignation. All three films share an opening pattern: first, a religious ceremony, then a celebratory party, then “business.” No doubt there are many other similarities. For me, the effect is to give a feeling of familiarity, the same old story, and with that a sense of fate. Michael will not escape his destiny, no matter how hard he tries. It is in Part III that Michael emerges as a true tragic hero, not just another gangster.

There is a progression in the series. Those who are trying to rein in the Corleones’ violent solutions to their “problems” get bigger. In the original, it was the New York police. In the second, the U.S. Senate. But here it is “the power of forgiveness,” represented by the good cardinal who hears Michael’s confession, then him as Pope, and finally, behind him, God. To me that gives Part III, despite all the critics’ downgrading, a richness and universality of theme beyond the first two Godfathers. In this Godfather, Michael emerges as a fully tragic figure. He wants to “get out of it.” He wants to become an honest man, as he had been at the beginning of the first Godfather, the “college boy” and Marine war hero. In Part III, he tries to get right with God but is defeated by fate, destiny, or simply the life he has chosen and lived in the past. Having killed, he dies alone and unloved. In a tragic irony, it was precisely his efforts to “protect the family” that made it necessary to protect the family.

I’ve begun to think of Coppola as having what we might call a “cross-cutting imagination.” That is, his mind seems to work by cutting from a scene of one locale or action to a scene of a totally different locale or action, making a striking contrast. This style is what made him a great director. For example, in the original Godfather he cut from the deep brown of the Don’s study and the “business” going on there to the bright colors, music, dancing, and general jollity of the wedding reception. Very dramatically, Copppola cut from the baptism of Michael’s nephew to the murders of the heads of the Five Families. In The Godfather, Part II, cross-cuts came to define the whole movie, cuts from America to Sicily, from past to present, from humble beginnings to vast wealth and power. In a more general sense these Godfather films cut from the “legitimate hypocrisy” of politics, government, and church to the franker corruption and violence of the mob.

In Part III the cross-cutting becomes larger in scope as Coppola moves from the Church to the “family.” He sets Michael’s apparently sincere efforts to become legitimate and to make the old Immobiliare into a new kind of global business against the deep, reactionary corruption in the Vatican finances. This is itself a cross-cut from fictional Michael to actual historic events: the 1978 death of Pope Paul VI and the election of Pope John Paul I followed by his sudden death and the Papal banking scandal.

Even larger, though, is the cross-cutting from Michael’s sincere and rather moving confession of his sins to the “true priest,” Cardinal Lamberto, and Michael’s subsequent lies and murders. In a sense, the whole film builds on a contrast between a man’s efforts to do good and the circumstances that, as Michael sees them, force him to do evil. Ultimately Michael is torn between spiritual and physical experience.

It is Coppola’s “cross-cutting imagination” that I think makes him a major director in the three Godfather films, The Conversation (1974), and Apocalypse Now (1979). What happened with his other films, who can say? But I’m grateful for this superb trilogy.