Enjoying: This is a puzzling movie. Don’t sweat it. Your efforts to read through it to some meaning or theme will only spoil it for you. Just let it happen.

The movie has a plot—alas, I almost want to say. Not much of a plot—a married woman goes from her lover to her husband to her lover again. But a lot of enigmatic things happen in the process. My summarizing them would defeat the purpose of this movie the way a roadmap would take all the fun out of a funhouse. Nevertheless, if you’d like to read it, I offer a synopsis on an adjoining site.

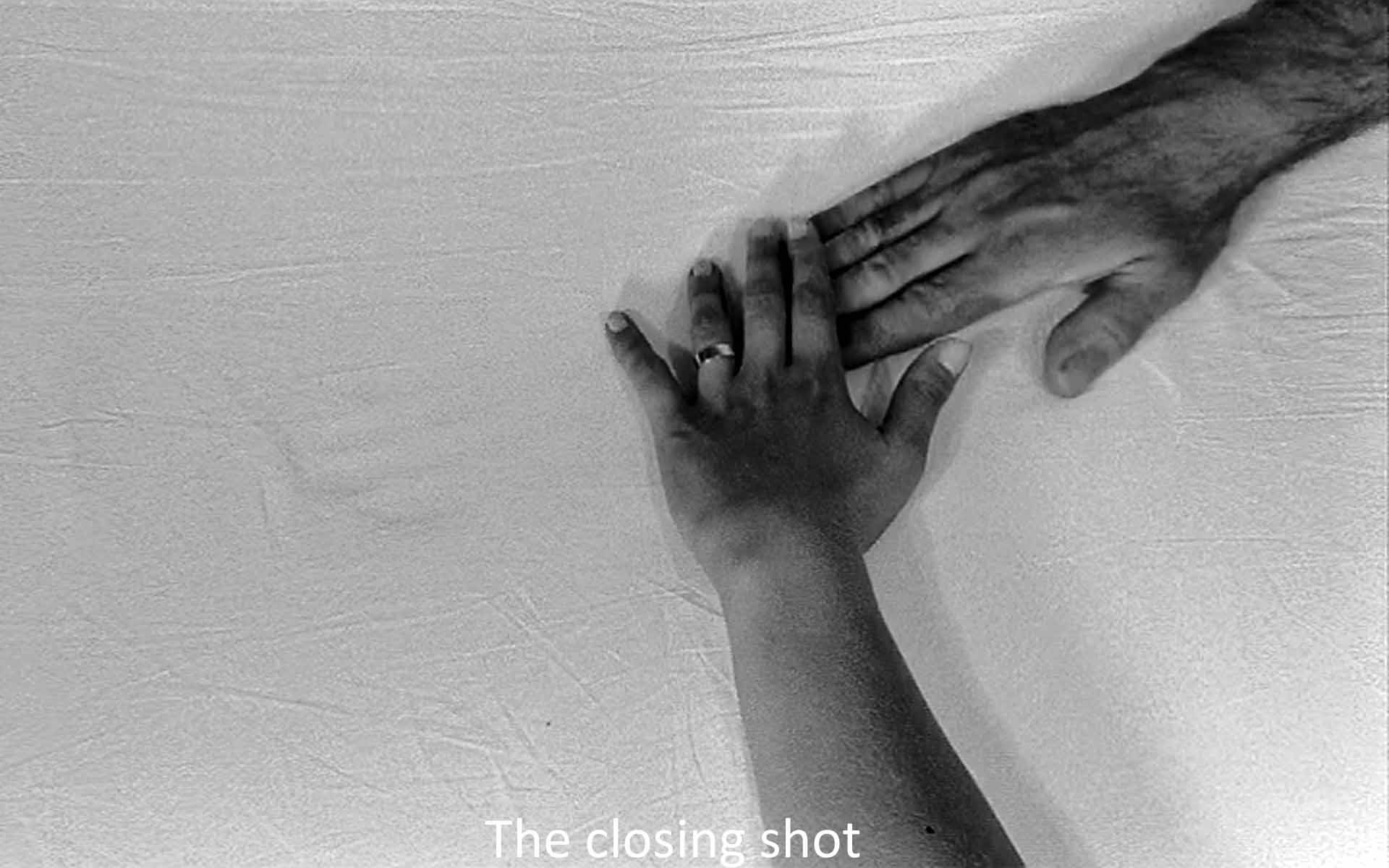

For all its postmodern discontinuities, though, this film builds on repetitions and contrasts like familiar modern films. It has lots of pairs. Twice we are told about the good Tele Avia television set Pierre and Charlotte own (associated with flight aviation). Twice we are told a joke about a Volkswagen making a right turn. Twice we hear “good night’s” to the child Nicholas. The film is preoccupied with breasts (two) and hands (two). Robert speaks at the beginning about wanting to be inside his love but he takes Air Inter (“interior”) to Marseille at the end. The film had opened with a shot of a plain white sheet with two hands, a man's and a woman's, coming into the frame. It closes with the same shot reversing.

These repetitions serve mostly to underline the more fundamental polarities of the film. The woman goes between a lover and a husband, each involved with flight and absence. She goes from taxi to taxi, lover to husband to lover. She and the lover pass back and forth a device to improve posture. They turn the car mirror first toward him, then toward her. She and her husband pass records, dishes, clothing, his child (from a previous marriage) back and forth.

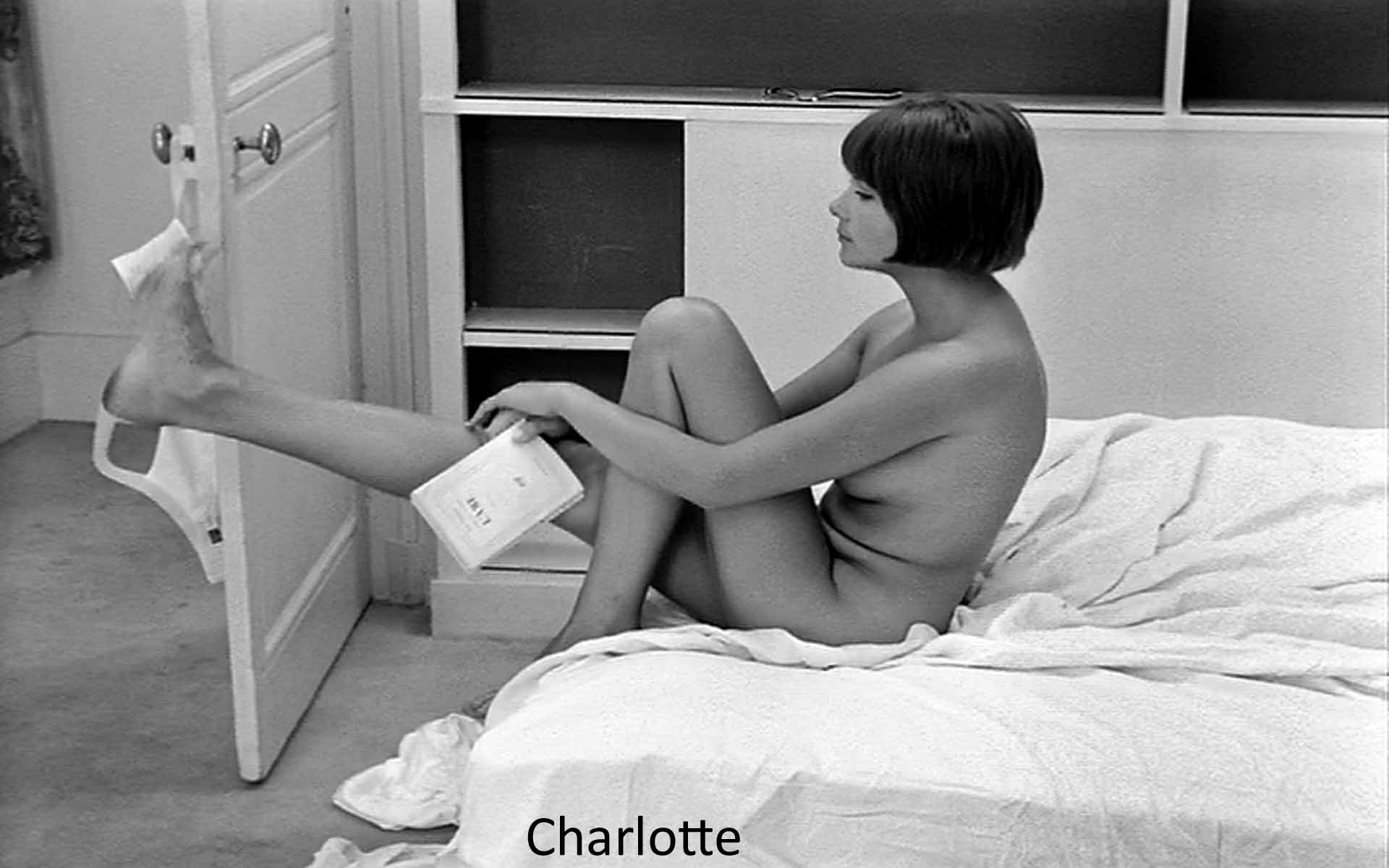

The interviews set up other dichotomies: past—present, male—female, intelligence—creation, age—childhood, pleasure—science, sex—conception, cleaning woman—gynecologist, pilot—actor, intellectual—child, “she knows”—“she doesn’t know.” But at the focus of them all is Charlotte (Macha Méril), the present, the woman with her sexe inside, at the center and inside her still another focus, the child-to-be, whose father we do not know. Her sexuality makes all these dichotomies inconclusive, undecided, unresolved.

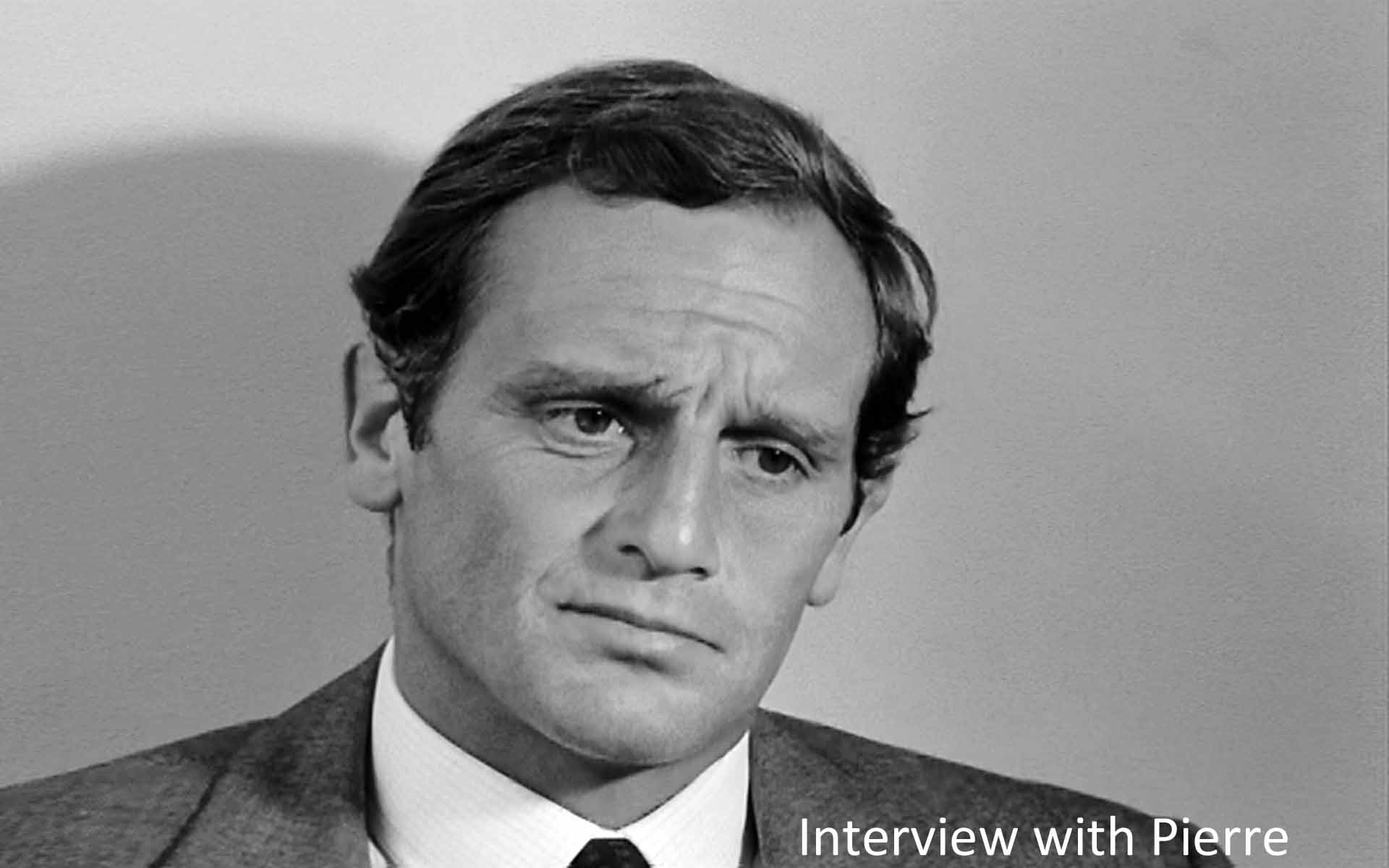

The interviews themselves are another kind of dichotomy. That is, the film moves between plot and interview—two quite different styles, one associated with narrative film, the other with documentary or television punditry, one advancing through events, the other through ideas, one with movement in the film frame, the other with just a talking head. The narrative film plot purports to give us the surface look of events. The interviews purport to give us the inside, what the character thinks—something the narrative film cannot do. In a way, I think Godard is asking, Do the interviews penetrate the surface of the narrative film? They cannot, since the speakers are still acting—as the last interview shows.

The action of the narrative film has a kind of A-B-A structure. That is, Charlotte starts out with her lover Robert (Bernard Noël), shifts to her husband Pierre (Philippe Leroy), then shifts back to Robert. The points of transition are marked by shots of an airplane and Charlotte and Nicholas on their sides and later by Charlotte’s falling in the street on her side. The match between opening and closing shots marks the completion of the whole cycle: “C’est fini.” There is, however, a turning point in the film, the interview with the gynecologist (Georges Liron). After Charlotte learns that she is pregnant, that there is a future implicit in her ambiguous present, Godard plays with words-within-words. We see DANGER (ANGE), and REVES (EVE), and Prenez Parti—"Take sides!" Choose! But we already knew she had to do that, and anyway she doesn’t do it.

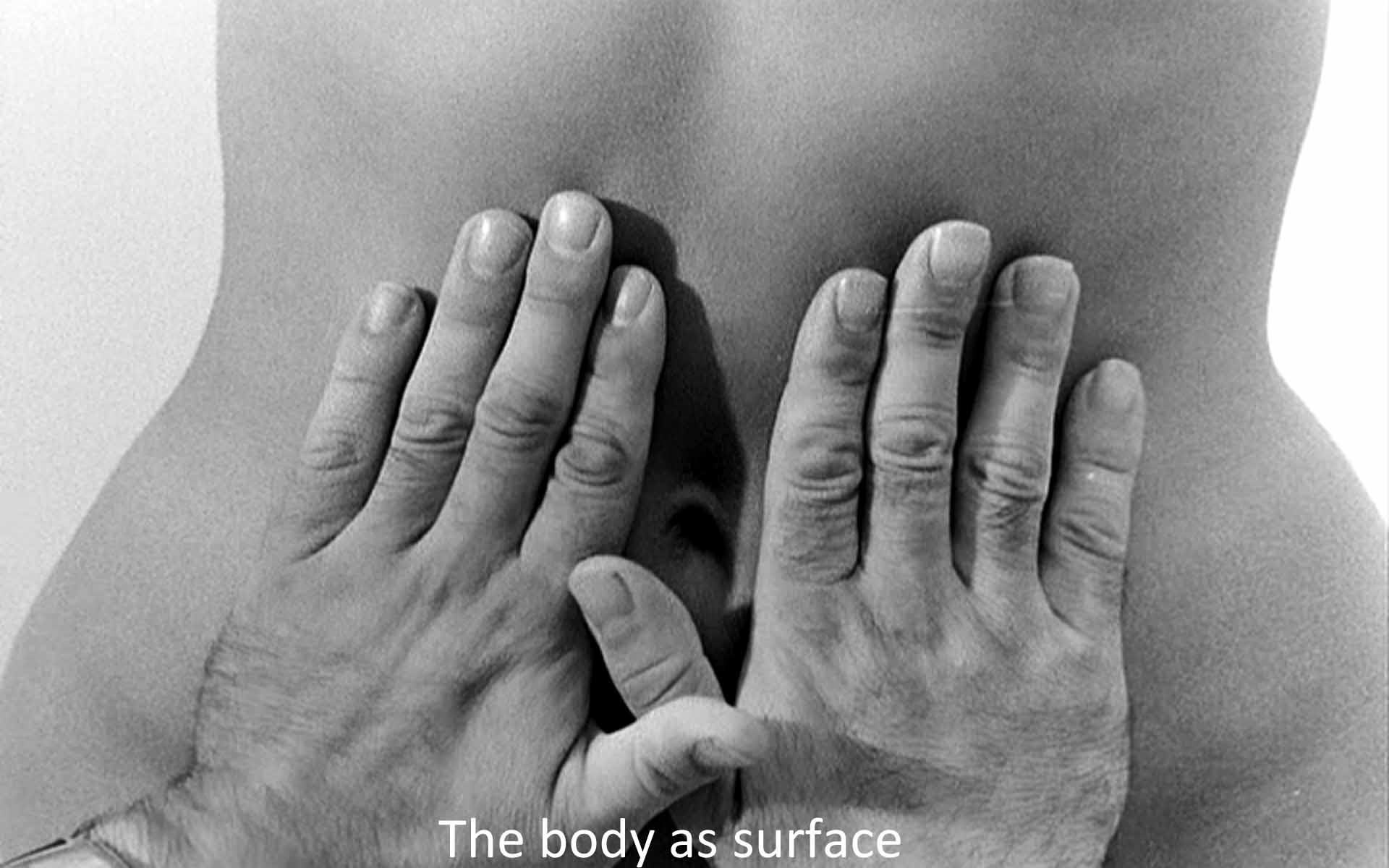

The film is preoccupied with surfaces: the bedsheets at opening and close, the texture of skin on arms and thighs, the hairy skin of legs or armpits, the anatomical book Charlotte looks at in the gynecologist’s office with its fold-out surfaces and layers. “You kiss me, but you are outside,” says Robert at the opening. Pierre worries about the surfaces of the records he has borrowed. On one record, a woman laughs over and over, but at what? The bedsheet at the opening (and close) equals the white surface of the blank film frame on which the whole film is projected. In effect, Godard is playing with a tension between a surface and what is inside or meant by the surface. The events of the film play on the surface of the surface, so to speak, the surface itself being an impenetrable enigma. But what is important is what is inside, what the characters are really thinking or the baby inside Charlotte.

I think this preoccupation with surfaces is why Godard uses so many photographs of written phrases: Demain (tomorrow), or main (hand). Hotel Cinema. High Fidelity. Libre (free, on the taxi meter). PASSAGE (PAS SAGE—not nice). Three times the characters say “Je t’aime,” but the film goes silent so that we have to lip read what they are saying. In effect, these commentaries are unnecessary, gratuitous, extra, and when we need them (the “Je t’aimes”) they aren’t there. In the same way, the talking heads—apparently ad libbed words—tell us nothing about what we are interested in: who will Charlotte choose? Which side will she take? Words, which should lead us inside the characters, don't. Instead, we are left with pictures of outer surfaces.

I haven’t counted, but I’d estimate that the most frequent image in the film is clothes. There is much putting on and taking off of clothes with attendant close-ups of hooks, straps, snaps, and garters. We see—and the characters talk about—brassieres, corsets, panties, slips, men’s undershorts and pajamas, underwear of all kinds, but mostly hers and mostly contrasted to her naked body, not the men’s bodies. The men are preoccupied with looking at the image of her body. Should she shave her armpits as in the American movies, or leave them unshaven as in the Italian? Did she use her husband’s Norelco? Did she leave her lover’s razor dirty? The magazines she looks at and the billboards she walks past are endlessly preoccupied with women’s bodies in or out of underwear. The still photographer at the swimming pool makes negatives out of models in bathing suits.

The people in the movie are absorbed in the tension between two kinds of surfaces, clothing and the body. And so am I, in the audience. For these people (and for me), desire is desire of the image, and love is love of the image of love, and self-love is love of the image of the self. That, it seems to me, is the point of the long opening sequence of Robert stroking Charlotte’s body: skin, hair. Throughout the film, she narcissistically cannot stop stroking her own hair. The body is a surface.

Clothing is a surface on a surface—a redundancy, and Godard packs this film with redundancy. 1964—the subtitle tells us what we already know from the copyright. The film is subtitled “A Film in Black and White”—and we already know that. Pierre speaks proudly of his automatic pilot, and his wife wonders why they need him to pilot the plane at all. Their dinner guest, philosopher and cinéaste Roger Leenhardt, tells a joke about a new German plan to kill all the Jews and the barbers. The German he tells it to asks, “Why the barbers?” And so does Charlotte. “I already have a child” she says, when Robert tells her he wants her to bear his child. Written titles on the screen during the dialogue between the two girls at the swimming pool duplicate what we hear them say. The film ends with “C’est fini” in the dialogue and a redundant “The End” in English on the screen. The last interview is with an actor who is acting an actor in an interview who is an actor who is (or is not) acting, and so on, through infinities of mirroring ambiguity/ surfaces.

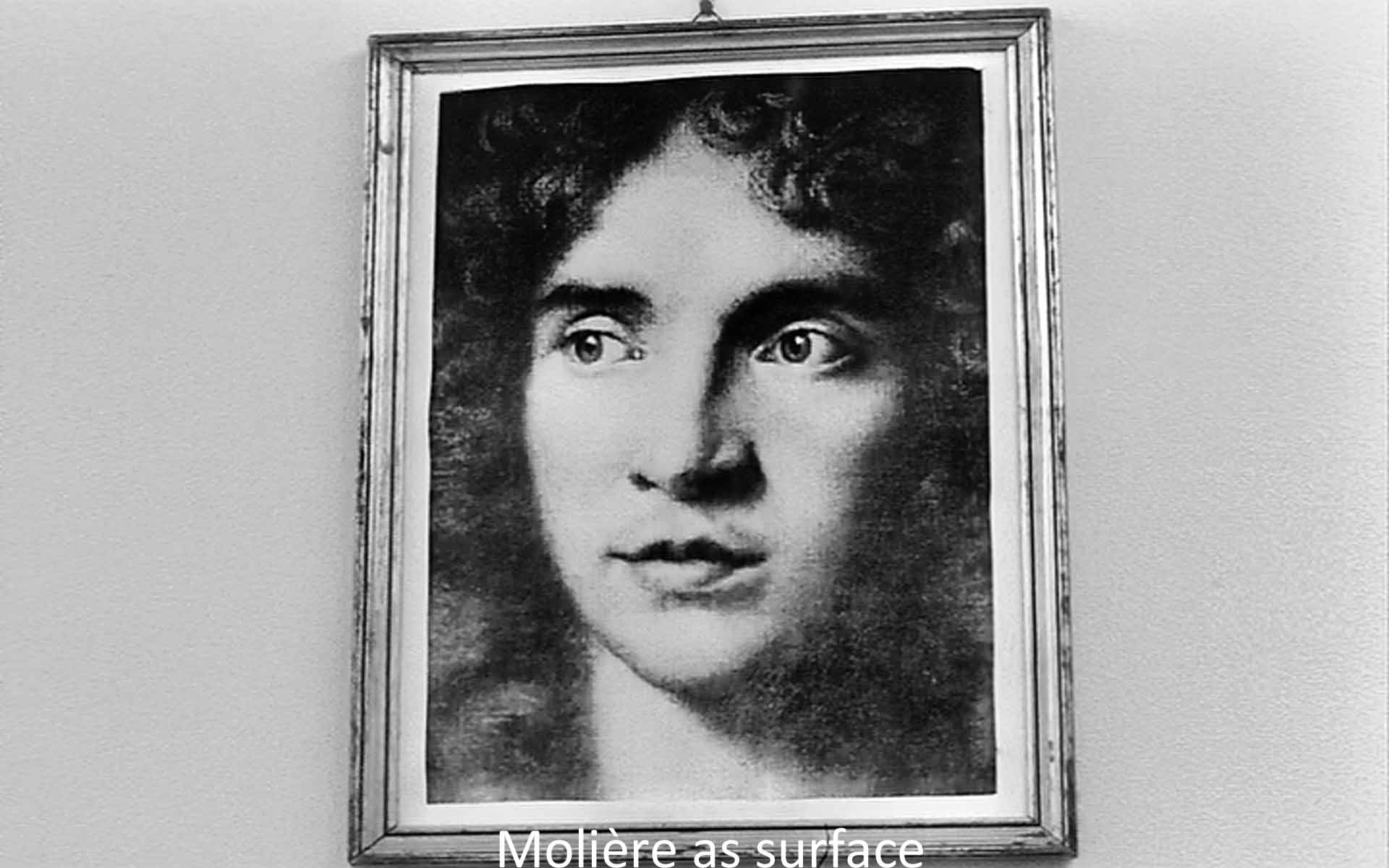

Godard introduces these redundancies, I believe, as images for the very idea of redundancy. In the same way he includes advertising, the myriad underwear ads in the women’s magazines and on the billboards or Pierre and Charlotte parroting the advertising copy for their apartment. I think the same theme underlies Godard’s inclusion of other works of art in his own work of art: Molière’s defense of comedy, Racine’ Bérénice, Beethoven quartets, Dietrich’s face (surely a work of art!), a picture of Hitchcock, a segment of Resnais’ Night and Fog, or Mme. Céline’s recital of a section from Céline’s Death on the Installment Plan. To take a picture of a picture (or of a movie) is redundant, unnecessary, like recording a recording. I read the seven interviews as another form of overkill—who needs them? They are, to be sure, interesting, but so far as the plot or characters are concerned, redundant, unnecessary, extra. Godard makes works of art tactile, objects to be treated as surfaces, not interpreted or read through to something else. In a strange sequence, Charlotte goes to a swimming pool where a photographer is photographing the women. We see what is inside the camera, the negatives—but they are as unyielding as the other surfaces, impenetrable like the asphalt on which Charlotte falls. They become surfaces like the bedsheet with which the picture begins and ends, surfaces on a surface, like clothing.

As I read the film, surfaces are complete in themselves and attempts to get inside are redundancies—these are the dominant themes of the film. To the complete woman, that is, the woman with something in her center, man and marriage are as redundant as a brassiere. Similarly, film is complete in itself. “Fragments” without conclusion, outcome, plot, or characterization are film in and of itself, pure film. Perhaps we could say Godard is illustrating some of the French postmodern claims about language: that signifiers, words, refer only to other signifiers, not to signified, meanings. Surfaces lead only to other surfaces. A film refers only to film.

Yet, as when we know the film is only a fleeting thing projected on a bedsheet, film itself is a redundancy. This is a film that criticizes the very idea of film. Images are redundant, superfluous. What counts is what is, and any image is a flight from that. When the final, redundant “The End” appears on the screen, I hear Godard, through Charlotte, saying, “This is extra. This is unnecessary. But so was the first time and so was the whole film.” This is a movie about a movie’s being only a long series of surfaces.

But it is also a movie about a woman who is pregnant and who doesn’t know whether by her lover or by her husband. What is inside remains mysterious and elusive compared to what we see on the screen, surfaces.

All art, it is said, aspires to the condition of music, and this is a film like music. It dismisses all reference to things beyond its own surface. But, at the same time, being a movie, being photography, it refers to inside its surface reality. This is a movie that in this and Godard’s other films of 1964-1976, criticizes and tests itself. Critic David Thomson calls it “one of the greatest runs of work anyone has had in film.” Godard hints at the stakes he is playing for by including masterpieces from Molière or Racine or Resnais, and I think he won. Image after image cumulates, both reinforcing and canceling out those that have preceded it, to make an amazing surface, a stunning work of art.