Michael Ondaatje (pronounced the way you might think) wrote a complex, brilliant, postmodern, poetic novel. Anthony Minghella (director) and Saul Zaentz (producer) made a visually beautiful melodrama out of it, thanks to the cinematography of John Seale and the editing of Walter Murch. More of that later. For now, break out your Kleenexes for the finale.

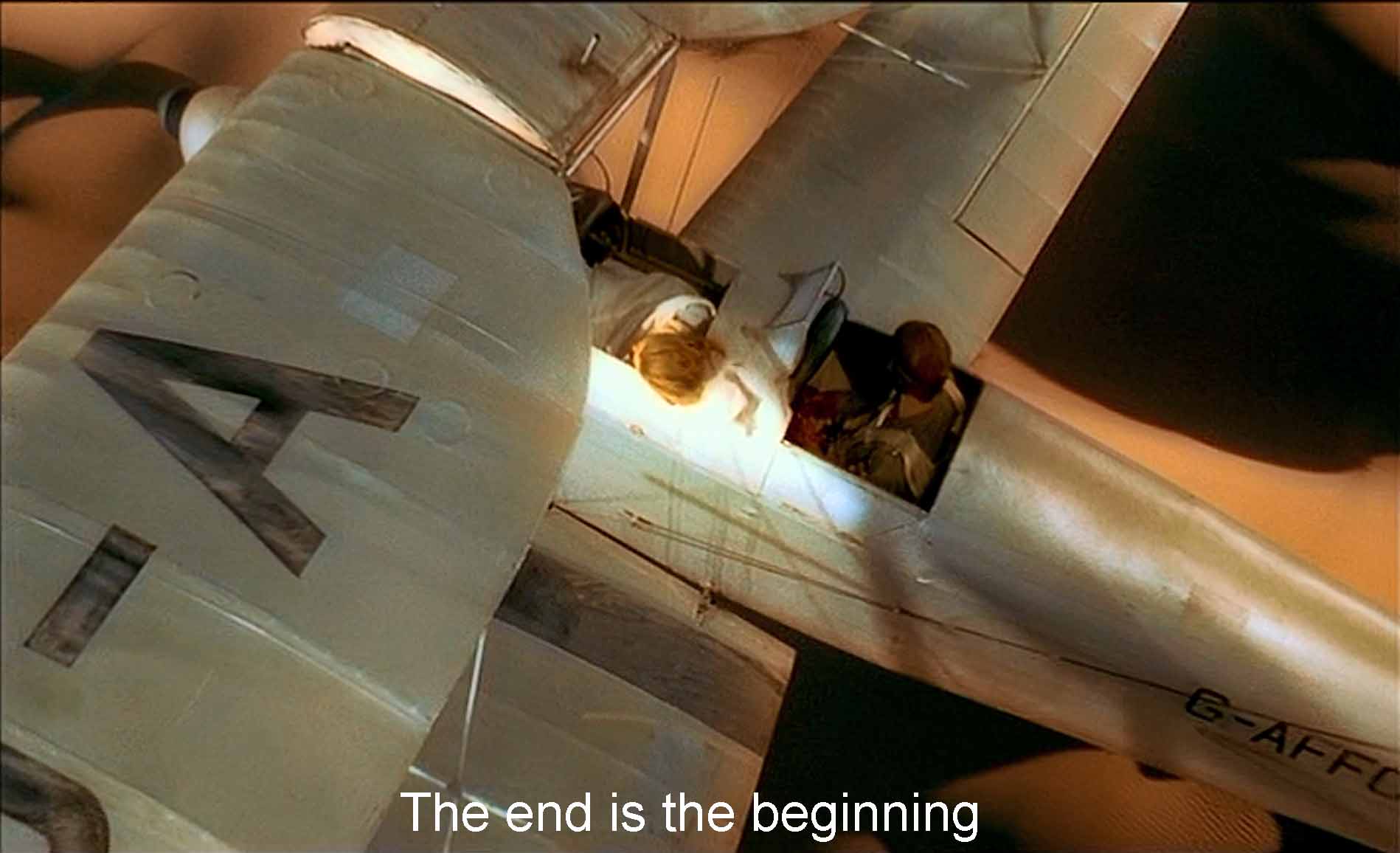

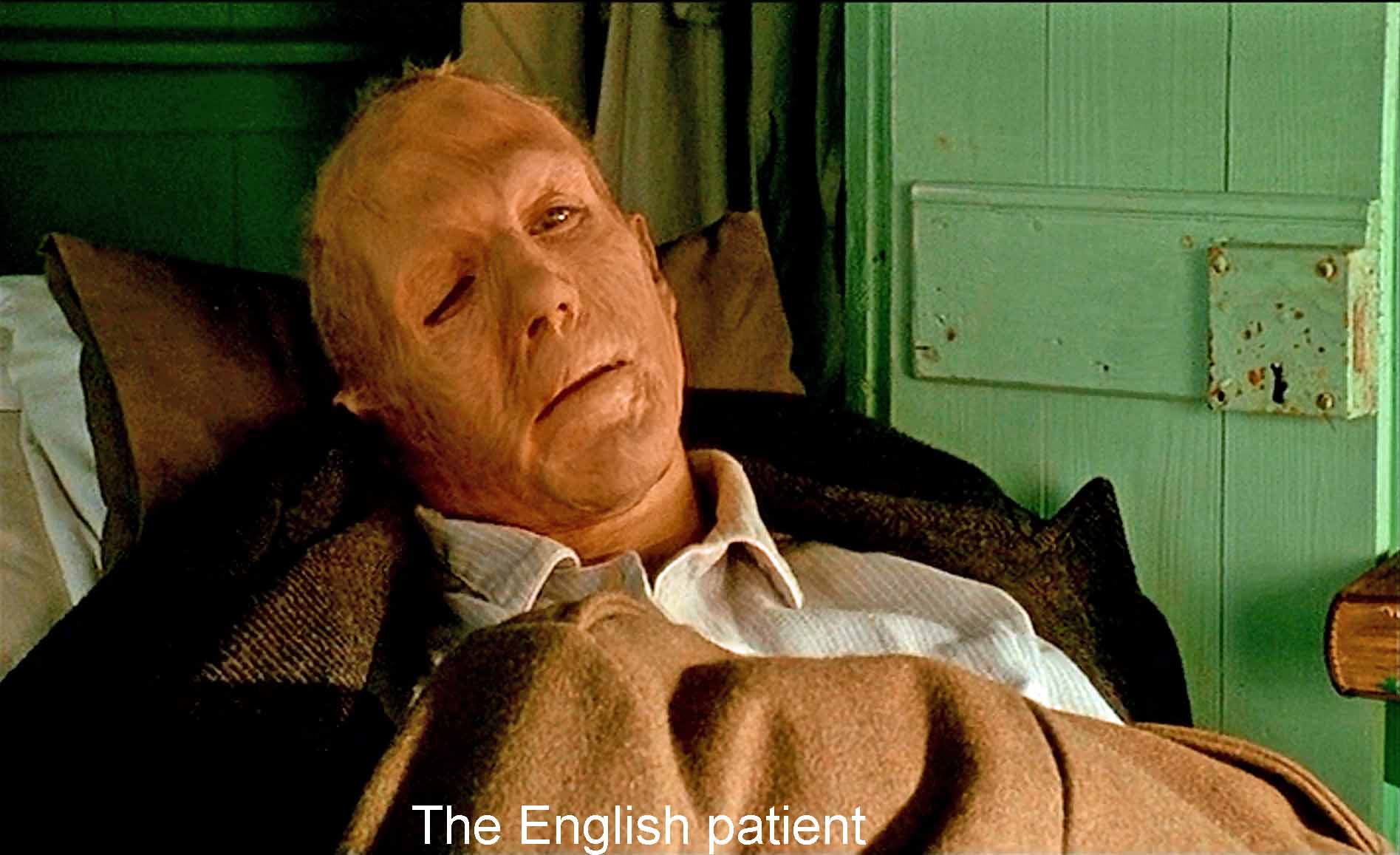

Here the first thing we see (in the film proper) is in fact the final event of the story. The whole story takes place during World War II, the North African and Italian campaigns. It’s told in flashback in chronological order (unlike the flashbacks in the book). “The English patient” (Ralph Fiennes) is an unidentified man horribly burned when his plane was shot down in the opening scenes. He has lost his memory and is identified (wrongly) as English. He is being nursed by a French Canadian nurse Hana (Juliette Binoche) who settles him in an abandoned monastery in a liberated section of Italy. The so far anonymous patient recalls in flashback being on a prewar international exploring team, mapping the canyons of the Egyptian desert and making what archaeological discoveries they could. Especially important are the cave drawings they find of people swimming that we saw under the credits. Swimming? In the desert?

The expedition is joined by a young Englishman Geoffrey Clifton (Colin Firth) and his glamorous, somewhat flirtatious wife Katharine (Kristin Scott Thomas). “The English patient” is Count László Almásy, a Hungarian. When Clifton, who is covertly spying for the British, is called away, Almásy and Katharine are left together, then swallowed up in a sandstorm. They fall madly, passionately in love. Naturally this must end tragically, and it does. The British re-take North Africa from the Germans and move on to Italy. There Almásy bit by bit remembers, flashes back to, his love story.

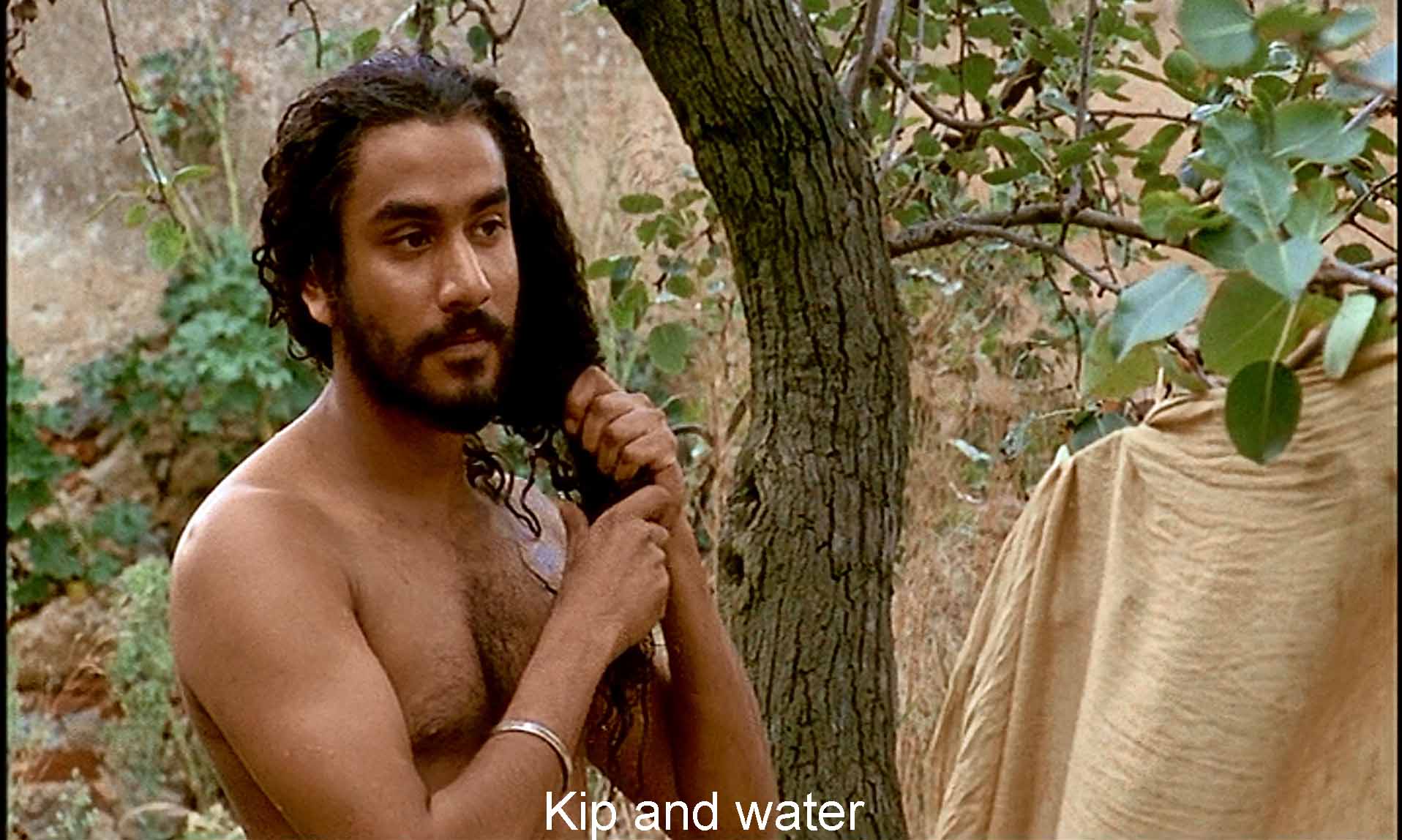

There is a secondary plot involving Hana. She and Almásy are joined in the monastery by David Caravaggio (Willem Dafoe), a Canadian spy whose thumbs the Germans have cut off. It is Caravaggio who identifies the English patient as Count Almásy whose information may have led to his mutilation. Caravaggio has come to get revenge. Then comes Kip, a Sikh lieutenant in the British army (Naveen Andrews). He has the perilous job of defusing mines and bombs. He and Hana fall in love, but when the British Army moves on he has to leave. They promise (vaguely) to meet. Finally Hana gives the English patient a merciful death by morphine.

Near the beginning of the film a wounded British soldier wants his nurse to kiss him. Another soldier asks to see someone from his home town. Much later Almásy muses, when Hana enjoys her Montreal connection with Caravaggio, “Why are people always so happy when they collide with one from the same place?” In line after line and scene after scene the film gives us its preoccupation with nationalities and boundaries and possession. (Why else would Hana play hopscotch?) All are bad, and it is up to love to transcend them.

Almásy sings all kinds of popular songs (mostly American). They are beyond nationality; everyone owns them. The exploring team was exemplary: “We didn’t care about countries, did we? Brits, Arabs, Hungarians, Germans . . . None of that mattered, did it? It was something finer than that.” Even so, the explorer team at the opening is, in a way, taking possession by mapping these archaeological sites, and their maps finally allow the Germans to occupy North Africa. The ultimate preoccupation with possession, of course, is the war with the British and Germans fighting over who “will own North Africa.” And “international,” as drunken Almásy complains, has become a bad word.

Nationality, boundaries, possession, war: these are the things that love tries to transcend—and melodramatically fails. With Katharine, Almásy tells us what he hates most: “Ownership. Being owned.” But later he will claim possession of her shoulder blade and her “suprasternal notch.” His and Katharine’s love breaks the bonds of matrimony, another kind of possession.

The film’s cyclical structure creates something indeterminate, without the clear boundaries of a linear plot, particularly in the opening and final scenes when we cannot tell who is doing the seeing. We do not “possess” the story until the very end.

The transverse story of Candaules and Gyges involves more possession. When the explorer team is spending a night in the desert, each does something to amuse the others. Katharine tells the story of Gyges and Candaules (from Herodotus, whose book is a symbol throughout of humans caught in history). Candaules, bragging about his wife’s beauty, invites Gyges to hide in their bedroom and peep at her nude. The wife catches him at it and gives Gyges the choice between murdering her husband and making himself king or of being put to death himself. He chooses the former and succeeds at it. Katharine tells the story in so shyly enticing a way that I think the men around her, notably Almásy, imagine seeing her rather than the queen, naked. King Candaules’ foolish act makes another instance of possessing another person.

The relation between Hana and Kip is a much milder thing. There is no question of either possessing the other. Rather, Kip’s job is to break connections in mines and bombs. In the ending, Kip is moved north, and Hana simply accepts his leaving with indefinite plans to meet after the war. Boundaries (racial, national, military) separate them.

Flight throughout the film is a way of traveling above and beyond boundaries—until it fails, that is, until Geoffrey Clifton crashes his plane, until Almásy is shot down. There is one lyrical scene of two tiny airplanes floating past huge ocher dunes. In another extraordinary scene (thank you, John Seale), Kip hoists Katharine in a sling (”flies” her) with a flare so that she can see some beautiful frescoes high up on church walls—again flying transcends limits..

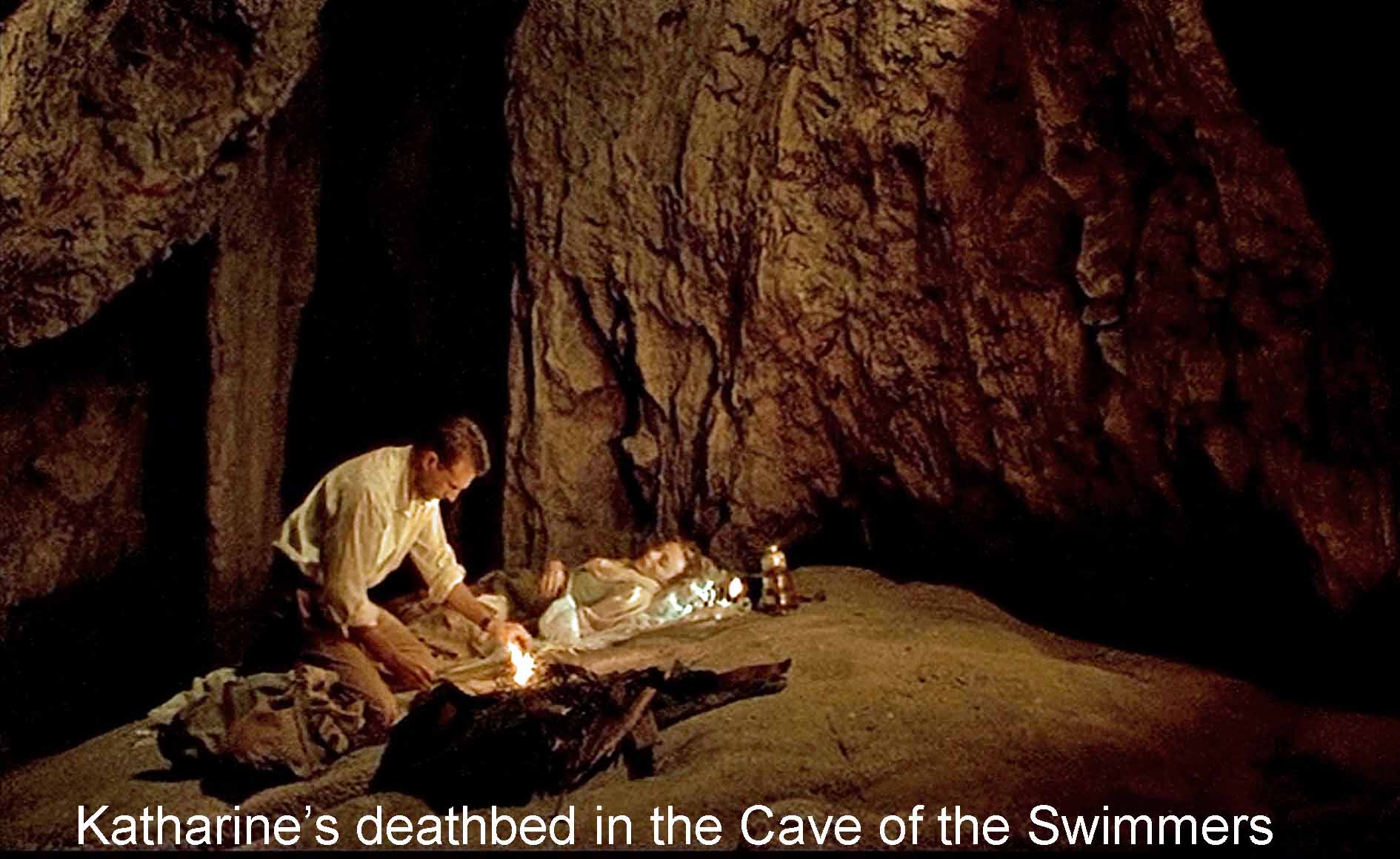

Flying suggests air, and the four elements, earth, air, fire, and water, permeate this film. We have earth, obviously, in the huge dunes and the vicious sandstorm that buries the exploring team, throwing Almásy and Katharine together. The many fires and explosions, the campfires and lanterns, all exemplify fire. Then, as Almásy writes, “the heart is an organ of fire.”

Most intriguing is water—those strange swimmers in the desert. Once upon a time there was water here. Water and liquids are identified with the women, Katharine in particular. Her husband says of Katharine, “She’s in love with the hotel plumbing. . . . She swims for hours. She’s a fish.” And, of course, there’s the scene where she gets in the bathtub with Almásy. It is she who so carefully draws the swimming figure in the image behind the credits. We also see Hana washing repeatedly, and there’s the morphine she gives out. Liquids flow over boundaries. Morphine ends boundaries.

The elements are all unbounded, a contrast to the boundaries and possession of the human institutions: war, territory, marriage, and, indeed, love. Hence the last shot of the unbounded sky. We would like to hold onto the people we love, but this film suggests that we can’t. The finale implies that we cannot even bury them, an ultimate irony.

When you make a film of so celebrated a novel as The English Patient, the bait that most movie reviewers snap at is, Is the movie “faithful” to the book. A silly question. As Hugo Munsterberg pointed out way back in 1916, in the first book of film theory, it is impossible for a film to be faithful to a narrative, because film and narrative are two entirely different art forms.

One, film is a visual medium; the less reliance on title cards, voiceovers, and even dialogue, the better. Two, the storyteller can spell out the states of mind of his characters; the filmmaker cannot. In compensation, filmmakers can show the look and sound of everything and everybody in as much detail as they like; the story teller had better not. (See the exhaustingly exact physical descriptions in the 1950s nouveaux romans of Alain Robbe-Grillet.)

By “fidelity” to a novel most people mean keeping the various incidents in the plot and making the characters look and act the way they are described in the book. Here the filmmakers (with Ondaatje working beside them) have converted his complex, poetic, postmodern novel into a very good Hollywood-style melodrama.

Melodrama—the term gets thrown around pretty loosely when people are talking about classic Hollywood style. Ben Singer’s definitive book points to: heightened emotion, particularly pathos; sharply drawn good and evil; lots of chance and coincidence; and an emphasis on violent action. You’ll find all of these in the movie of The English Patient (with a sadistic German officer providing the evil). As with any genre, there is good melodrama and bad melodrama, and this is surely good melodrama, but melodrama it is. And let’s not kid ourselves that the film is “faithful” to the novel. In the novel Hana is the most important woman, and the book has a complicated back story of Caravaggio and Hana in Montreal—omitted in the film. Most importantly, Minghella gives us romance instead of Ondaatje’s development of an anti-racist and anti-colonial theme; that idea gets reduced to Kip’s meager discussion of Kipling. In the book Kip is infuriated at the dropping of the A-bomb on Hiroshima. They would not have dropped it on a nation of white people, he bitterly complains, and leaves.

Let’s take this film for no more than what it is, a beautiful—and it is beautiful!—revision of a fine novel made with the writer’s cooperation and wisdom, postmodernism converted to melodrama.