In 1963 when 8½ landed on the international film scene, the professionals gave it all kinds of prizes: two Academy Awards and three other nominations, the New York Film Critics Circle (best foreign picture), the 3rd Moscow International Film Festival, and so on. It was shown out of competition at Cannes, but received enthusiastically. In 1963, though, reviewers, me included, were somewhat nonplussed. I reviewed the film back then for the Hudson Review, and like most critics of the day, I was disconcerted by an autobiographical film. Other reviewers found 8½'s mixture of realism and fantasy confusing. Since then, critics (as opposed to reviewers) have written about and written about 8½ less impressionistically and more analytically: at least seven books, two collections of essays, and more articles than I could shake a footnote at. Like virtually all writers about this film, I've come in 2015 to be as enthusiastic as I was negative in 1963.

8½ is autobiographical. Its hero is a film director, Guido Anselmi, played by Marcello Mastroianni, His name is a combination of a poet and a painter, both of women. Guido means "guide" as this Guido will more or less do. Anselmi means "helmet of the gods," and presumably this refers to the hat, like Fellini's own, that Guido wears throughout. Guido stands for Fellini himself making this film, but he is blocked.

8½ weaves three strands together: Guido/Fellini's professional life in making 8½; his personal life with wife, mistress, and friends; and, binding the other two together, his inner life of dreams and fantasies.

The film opens with a dark, mysterious dream (of which more later). Guido wakes from the dream at a spa where he is "taking the cure," that is, drinking the waters but also making his film. We first see his face at this point, as though his very identity grew out of this therapy. Guido's problem is that he has made a smash hit, like La Dolce Vita, and what will he do next? Everybody wants to know, most of all, Guido.

At the spa's fountain (water always being transformative for Fellini), he has his first healing sight. He imagines a beautiful girl (Simonetta Simeone),"young yet ancient" (he later tells us), offering him a glass of purifying water. The vision stands as a moment of silence in a cacophony from the Ride of the Valkyries accompanying lines of ancients tottering to the magic waters, gossips' chattering, priests, and middle-aged (to put it charitably) women peeping into the camera. (Fellini loves to photograph faces coming in and out of the frame. He sought these faces out at an aristocrats' retirement home.)

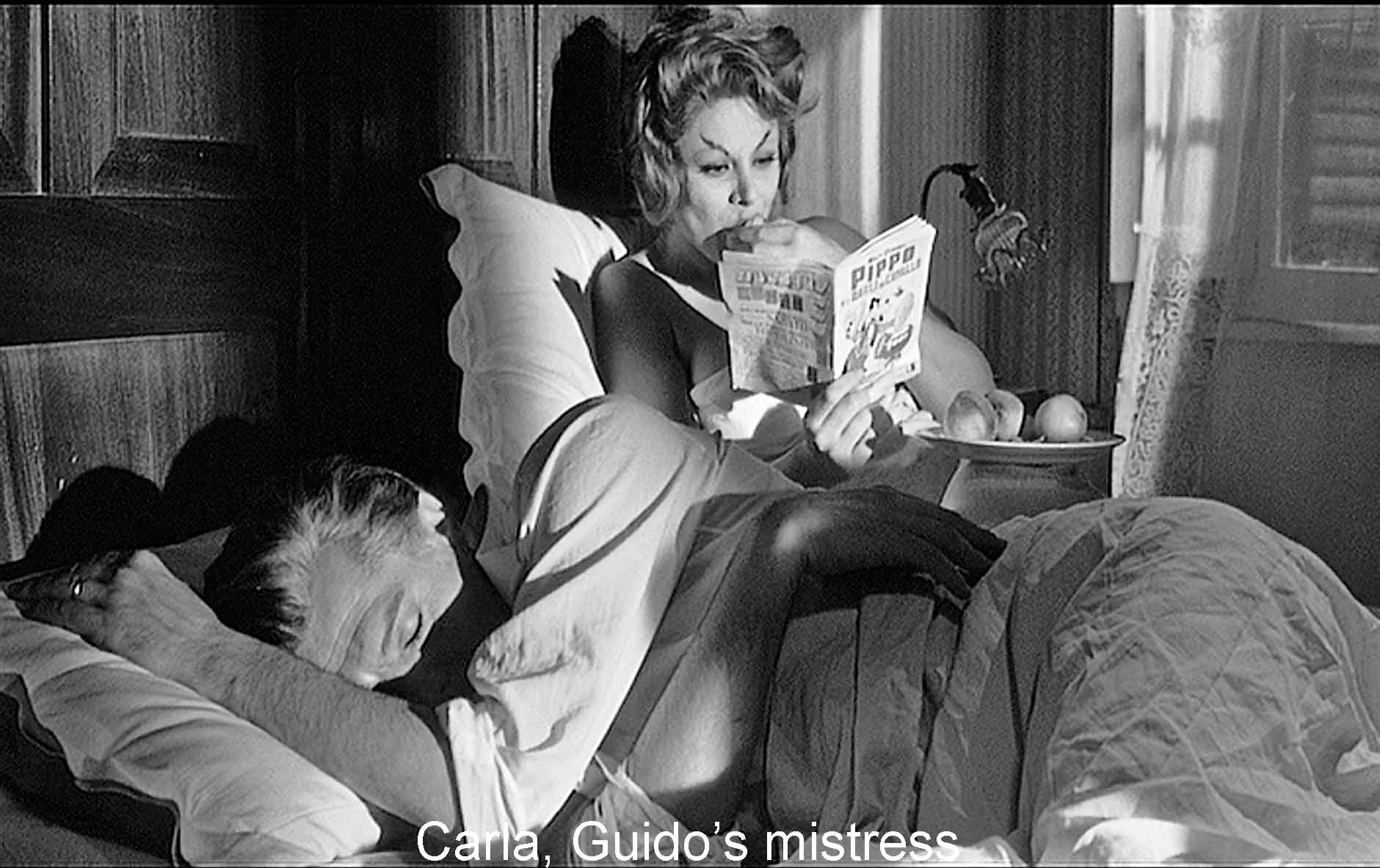

To look at others' faces at is better than to be looked at, sight is better than sound, and images are better than words (as in La Dolce Vita). Sound embodies the wordy criticisms coming from his snide collaborator on the script, Daumier (Jean Rougeul). Guido turns from him to find an old crony, the second of many references to aging. His friend is being rejuvenated by his young mistress, Gloria (Barbara Steele). Elfin and existentialist, a daughter to this father, she is attuned to flowers, and she inspires Guido to go to the station and meet his own mistress, Carla (Sandra Milo) as she arrives at the spa.

As preoccupied with clothes and chatter as the fey Gloria was with nature, Carla pops into bed with Guido—after he has gotten her to make up as a prostitute, parade herself, show him her body, and generally bestow on him what I take to be a basic theme for Fellini, the gorgon-like, all-powerful image of woman. His subsequent sleep is troubled by another dream that develops the father-strand of his current life. He turns (in the dream) from his loving mother to his mild father (Annibale Ninchi) who wants his tomb built higher, who frets with the producer about his son's "failure," and who tries to drag him into the ground. Guido turns to his mother, but she has been transformed into Luisa, his wife (Anouk Aimée). Men, in this as in other Fellini films, try to rise, but sink down, grow old and die; women offer life.

Life at the spa means going to the evening entertainment at the spa with the producer, his mistress, a pesky American journalist trying to interview him, various functionaries and friends, notably the old-friend-and-young-mistress. Now she preoccupies everyone with the almost inaudible "happy waters" bubbling under the ground. As the evening itself bubbles into a stream of empty chatter, the program peaks with a satanic or Death-like telepathist (another old friend of Guido's [Ian Dallas]) and his mindreading lady. Reading, not bodies like a film director, but minds, they elicit from most of their subjects' words. Not so Guido—they get from him a series of nonsense-syllables (again, downgrading words). The word is ASANISIMASA. It is the Italian word for "soul" or the Jungian anima (the female principle in the psyche), transformed by a kind of pig Latin that inserts extra syllables. The word leads to another dream-sequence.

His loving and seductive Mama (Giuditta Rissone) scoops up her darling Guido (a boy again) and carries him into a vat of grapes for "a bath" with the other children screaming and squealing as they trample the grapes. In effect, he plays Dionysus to his mother's love-goddess, but as he goes to sleep his sister tells him the magic nonsense-syllables, asanisimasa. She says they will make the eyes of his tomcat uncle's portrait seek out a buried treasure—a capsule statement of the film's male principles: looking, lust, verbal knowledge, and money. The magic word will make a picture move, just what Guido cannot do, make a moving picture.

Meanwhile, back at the hotel, Guido ogles a real woman gently murmuring into a telephone, "I forgive." She is an adored movie star from Fellini's youth (Caterina Boratto), but instead he gets an indefatigable French actress (Madeleine LeBeau) trying to find out about her "part." Guido retreats to "the production office," a helter-skelter of photographs of girls, drawing boards, a mock-up for the new picture's space ship, one irretrievable lecher in bed with two prostitutes, and an old man who complains about growing old. Like Guido's father in the dream, he tries to make Guido sink and fail.

Guido goes to bed, where he has another healing vision of the "young yet ancient" girl, now a chambermaid who seduces him as he lies on a mound of photos of actresses. She laughs at the words of men and books and murmurs that she wants "to create order and cleanliness." Guido lacks just those things, and a chambermaid would seem to be just the person to provide them.

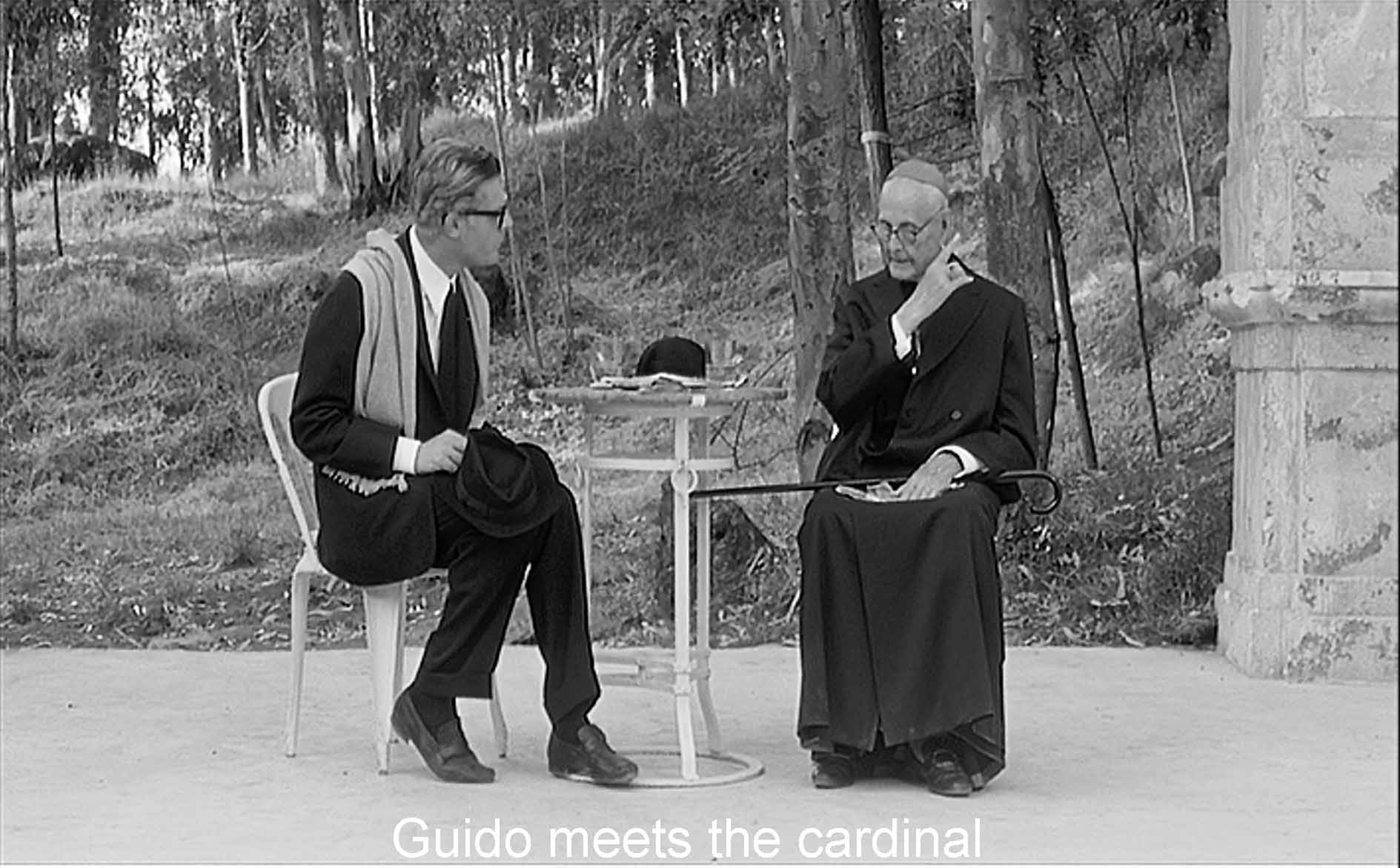

Unfortunately, his producer insists that he talk to a cardinal for guidance on the film. The cardinal, however, speaks only of a bird's sobs for Christ, while Guido, staring at a peasant woman, lapses into another dream. He is a schoolboy again, resorting to Saraghina (Eddra Gale), a great mound of a prostitute-by-the-sea, who puts on a hilarious rumba for her enthralled pre-teen audience. Two priests from school come and hale Guido off to punishment and shame (in handsome patterns of black and white)—but the boy eventually goes back to her anyway. ("Is this to be a film about the Catholic conscience in Italy?" the journalist had asked.)

Guido next turns up in a Dantesque sequence where all the characters, wrapped in toga-like sheets, descend to the inferno of the steam-rooms (men and women separated). He is summoned again to see the cardinal in his steam bath. (Earlier some ecclesiastical functionary had said he could not make a movie in which the hero meets a cardinal in a mud bath.) This time the Cardinal can only urge Guido to remind himself, "Outside the Church, there is no salvation," the words of Origen (whose achievements, as I remember them, included allegorizing the Song of Songs and castrating himself).

When Guido flees again, he finds his wife, and for a brief time they are happy and loving until the producer insists on taking the whole crowd out to the fake launching-pad he has had built for Guido's picture—although Guido as of this moment has not the slightest idea of script, cast, or theme for the film or what to do with this huge construction. The towering network of beams in the gantry seems to represent an expensive superstructure of lies, the intellectual superstructure that is about to be erected on Guido's movie, and also the lies he has told his wife. Indeed, when Guido and Luisa go to bed that night, they fight bitterly over Guido's infidelities and deceptions.

The next morning, the fight continues when Guido's mistress turns up at the cafe where they are breakfasting. Guido retreats into the sixth and most famous dream-sequence, the harem scene. He returns home on the Feast of the Epiphany(!) to a house like his mother's where all his women live as houris running about in the steam-bath sheets, loving him, never jealous of one another, always peaceful, submissive, and seductive. In this glorious male fantasy, all the women greet him with joy as he gives presents all around to Gloria, Carla, Saraghina, the mysterious, majestic "I forgive" lady, and so on. His wife returns the favor by presenting him with a new black girl whom he had admired. They bathe him, bundle him up in sheets as his mother had done (she's there, too), and all is tranquility until his first actress objects to being sent upstairs where the ladies who are "too old" are kept. A great hue and cry follows with the ladies insisting that they should be loved until they are seventy. Finally, Guido lays about him with a long bull whip—to their great delight: "He's like this every night." His wife restores peace, Guido makes an after-dinner speech, and she resumes scrubbing the floor.

He awakens into a viewing of all the screen tests, old and new, of the actresses he has interviewed for this new film (a kind of celluloid harem), and, in a little after-piece to the harem dream, he has Daumier, the wordy writer who has been criticizing his script, hanged. From this point on, Fellini's movie takes a unique turn—the movie creates itself as it goes. The screen tests show actresses acting out events we have already seen that could not possibly have been filmed previously—words spoken in momentary passion by Guido's wife or mistress, his own memory of Saraghina, and so on. At the same time, as Guido repeats the lines to the screen, they constitute a dialogue with his wife a few rows in front of him. The barriers between art and life fall down. To some extent, the film has already been doing this—we knew about meeting the cardinal in the mud bath before Guido met him there (or was it a steam bath?). The launching pad is just as tenuously connected to 8½ as to the picture Guido is ostensibly making.

The screening of the tests ends when Claudia Cardinale, in her very proper person, appears. She looks quite like the girl he has dreamed of as the "young but ancient" chambermaid in the healing visions, and he now wants her to play the part. She insists that the trouble with the man in the film (who is, of course, Guido and Fellini) is not his lack of religiosity, but his inability to love. Yet, when Guido confesses there is as yet neither part nor film, she accuses him of betraying her (his Muse?) and leaves.

The producer bulldozes Guido into a huge party cum press conference at the launching-pad to celebrate the start of shooting on his film (as yet neither cast nor scripted). There, baffled by the jabber and squawk of the word-mongering journalists ("He has no ideas," "He has nothing to say," they shrill), Guido crawls under the table (as he did to escape his mother's dunking him in the wine) and blows his brains out with a revolver thoughtfully provided him by a public-relations man. After this self-sacrifice, his wife comes to him (apparently in dream, but the usual boundaries are utterly blurred at this point). Guido makes a very hammy speech about love and giving oneself, but surely if Fellini has any taste at all, this is parodied by what follows: the most moving of the dream-sequences and the high point of the picture.

All the characters from his dreams and fantasies, father, mother, mistress, wife, prostitute, emerge in the same white as the girl of the healing vision. They are somehow purified, brought to order (by the whipping? the screen test? the death and rebirth?). A clown band appears, led by a little boy, and the Death-like mind-reader forms the characters into a line of march like a Totentanz. Then down from the top of the launching-gantry pour all the minor and major characters of the film (earlier, the producer had complained about the cost of all these extras). The mind-reader forms them into a long line, although the cardinal is excused. They begin to dance along in time to Nino Rota's wonderful music, round and round the launching-pad. As the darkness falls, they disappear, and one by one the members of the band take their leave. Finally, only the exquisitely evocative little boy is left, dressed in a white version of Guido's black student uniform, looking like a toy policeman as he plays his flute, the purified director of it all, the incarnation of Fellini's sense of wonder. He has ordered the disordered personages of his disorderly mind into images of cleanliness, light, and innocent acceptance. Fade out, and against the black screen appear the characters' names, white still, and finally the great baroque 8½ in white lines against the black background.

What was Fellini up to? As in La Dolce Vita, he was turning people into mere images and sounds. He flaunted his fantasies about women: they are either all-powerful good or all-powerful bad, either a virgin-mother-goddess who would bring utter happiness and fulfillment or a Saraghina, sexual sin incarnate. In comparison, men (Daumier, Guido himself, his father) are impotent creatures of words and thoughts, empty. For instance think about the two cardinali in this film. There is the male cardinale, an old, incoherent man nattering on in set speeches about guilt and salvation and the Church, clearly missing the point so far as Guido/Fellini is concerned. The other is Claudia Cardinale, a Muse, a goddess whom he had hoped would bring cleanliness and order and sex and free up Fellini's imagination. But, as it turns out, he is too weak and confused for her help. He is just another helpless male.

One random thought I had recently as I was watching this film yet again was that it is Fellini's answer to Ingmar Bergman. I began to notice similarities among the differences between Bergman's films of 1955-1960. and 8½. For example, Bergman's Seventh Seal ends with a dance of death. That particular image, Bergman's typed characters silhouetted against a brooding sky as the allegorical figure of Death leads them off in a dance, became the iconic image of avant-garde cinema in the late 1950s. Fellini's dance of life at the end of 8½ exactly parallels, contrasts with, and comments on Bergman's dance of death.

Contrast Fellini's final dance of the human comedy with the statement of the intellectual, Daumier, in 8½, at his first interview with the filmmaker about the script he has just read. "Your main problem is, the film lacks ideas, it has no philosophical base. It's merely a series of senseless episodes... It has none of the merits of the avant-garde film and all the drawbacks." I think it's hard not to say that Fellini was feeling competitive with this other avant-garde filmmaker so full of philosophy and ideas.

Peter Bondanella, in his massive 1992 study of Fellini, shows how Fellini's decisive encounter with Jungian psychology led to his interest in dreams and (starting in 1960) his keeping of dream notebooks. His interest in dreams led in turn to the dreams, surrealism, and metacinema of 8½ (150-163).

It is in 8½, it seems to me as to most critics, that Fellini finally and decisively broke with realism, turning wholly to fantasy. Indeed, that is what this film is about. He shows us how difficult it was for him to go off into this new kind of film. He shows us how everybody around him doubted what he was doing, his producer, his assistants, the press, the critics, the intellectuals. He shows us his helplessness as he tries to make a totally new genre, new for him, for anybody, really. All this happened in real life: Fellini deliberately manipulated the press to make it happen. As Fellini so often pointed out, though, Guido never succeeded in making his film, but he, Fellini, did.

In general, I see Bergman's own preoccupation with tormented intellectualizing as against the simple appeal of life, running all through his films from Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) until the time of 8½ (1963). If I keep Bergman in mind as I see 8½, the figure of "the intellectual," Daumier, becomes important. Notice how Daumier even looks like Bergman.

When Guido wakes up from his opening dream, Daumier is the first person he sees from his film world, and he is the last person Guido sees before the dance of life at the end. His name is that of an artist who brilliantly combined words and caricature (Fellini was an expert caricaturist) to create cartoons of acid social criticism. In 8½, Daumier is the spokesman for the word. He is the intellectual, committed to verbal meaning and social criticism. He beckons, indeed commands, exactly the opposite path from the one Fellini-Guido is finding for himself. His name is French, and France was certainly the center for making intellectual comments on film in those days and perhaps now. Daumier reminds me of Steiner in La Dolce Vita, the failure of words and intellectualism. "You are.... primitive as a gothic steeple," one of Steiner's friends tells him. "You're so high that our voices grow faint in trying to reach up to you."

That image brings me to my second random thought: Why did Fellini build the launching pad? One particularly fine study of Fellini up through Juliet of the Spirits in 1965 is Peter Harcourt's. He comments on a rather peculiar image that recurs in Fellini's work, the random structure: He points to the beach structures in I Vitelloni, the metal scaffolding next to Cabiria's cottage, and the metal swing on which we first see the White Sheik. But the quintessential useless structure to end all structures is the launching pad in this picture. Harcourt suggests that the people walking up and down the structure in 8½ are like the little boys who are constantly clambering around the poles outside Cabiria's bungalow. He concludes that both sets of climbers continue a theme in Fellini of purposeless activity, "a kind of physical meaning to the absurdity of life," "movement without direction, life essentially without a goal" (11-12).

I think that makes sense, but I see another possibility. These useless constructions go up. They point to the sky. To my mind, they connect to another theme I see in Fellini, the vertical, the theme of altitude. We first see the White Sheik high up on a swing. We can hardly forget the airborne statue of Christ that opens La Dolce Vita. In the opening dream in 8½ Guido flies high, and is pulled down in an Icarus fantasy of flying and falling. His father wants his mausoleum built higher. In other words, I think we are looking at a good old-fashioned phallic symbol. They seem to me linked to phallic striving, to male aspirations, pretensions, and intellectuality. Steiner was like a gothic steeple.

Following out my associations, I notice that 8½ involves various agings: Guido's aging, Guido's father's death, the assistant that Guido/Fellini dismisses as "old man", and Fellini's own aging. Many men fear aging as a decline in sexual powers, a phallic loss.

As many people have pointed out, this motif of verticality recurs in Fellini's work. David Herman tells us that Fellini himself spoke before 1963 of "the fear of falling, of being buried.... Each day, each minute, there is a possibility of losing ground.... of falling toward the beast" (258; Herman is quoting an interview with Gilbert Salachas). When I put Fellini's words alongside his images of men trying to be high or flying, I hear him complaining: they demand that I try to do these futile, even ridiculous male things. I have to show abstraction, philosophy, ideas, social criticism, religion, this "high" stuff. If I fail, I fall. I will be engulfed, overwhelmed. I will drown.

This is the fear behind the dark, black dream that begins the picture. The hero is blocked (as Guido/Fellini is in making this film). He is stuck in a silent traffic jam, locked in his black car, staring at the people in the surrounding cars and they at him. A noxious vapor comes from the passenger side (where Daumier will sit in the finale). Guido begins to suffocate (later in the film he will speak of "strangling in his own emotions"). He crawls out the top of the car and floats off into the sky, like the Christ at the opening of La Dolce Vita. He rises above the huge scaffold of the launching pad.

Fellini cuts abruptly away to a man in a cloak riding a horse along the seashore, silhouetted against the sunlight (perhaps another echo of The Seventh Seal). A second man is lying on the beach—we will see both of them later, as part of Claudia Cardinale's entourage. The second man pulls on a rope attached to Guido's ankle. As he does so, he calls out to the cloaked rider, "Avvocato, lo preso," literally, "Lawyer, I've got him." The fact that one of these men is a lawyer (with a skull medallion on his forehead) suggests that this rope refers to some contract that ties Guido/Fellini to making the mysterious, intellectual film that uses the scaffolding we've just seen. Contractual obligations tie Guido's soaring fantasies about Cardinale as a Muse to the low practicalities of actually making a movie. The men pull Guido down into the sea. The lawyer cries, "Giù, definitivamente." "Down, definitively down." And Guido wakes as he falls into the sea, wakes to the doctors and "la cura," the cure, the therapy, if I can use that word.

As I read it, the dream deals with the fear of being blocked, suffocated by a vapor from the "passengers" involved in his film. Flying and verticality express phallic wishes, if you will, and the dream associates them specifically with Guido's film project. He tries to rise, to soar out of the blockage, to fly, and the spacecraft launching station serves as the phallic symbol of that wish. But he is pulled down by his contract to make a film, and his phallic failure ends in therapy.

Therapy. That's a third random thought. Guido is undergoing, or trying to, some kind of therapy or psychotherapy at this spa with supposedly curative waters. A number of psychoanalysts have written about 8½ as a failed attempt at a cure for Guido's blocked creativity, and they conclude that the treatment failed because Fellini's pictures after 8½ are—and the critics generally agree on this—less successful than La Dolce Vita (1960) or 8½ (1963).

Fellini is stifled in his dream, but wakes to doctors who don't give him what he needs. His mistress, his wife, Claudia Cardinale, his producer, his film crew, none of them give him what he needs. At the same time, he is not giving other people what they need. His producer who wants him to cast the film, his staff who want him to start shooting, the actress who wants to know about her part, the writer who wants themes in the script, the journalists who want to know his ideas—they all need something from him, but to none of them does he give what they want. And what does Guido give them? Fantasy. Dream. Escape. The answer Fellini makes to his and Guido's and everyone's needs is to imagine, to fantasize total gratification, in effect, to make movies. You satisfy your needs, not through reality, but by play. The images of satisfaction in 8½ are Guido fantasizing with his mistress, Guido in an idealized childhood, Guido in the harem scene, Guido at the end in the dance of life. All unreal. All fantasy. Guido/Fellini replaces the practicalities of film making (producers, screen tests, money) with fantasies and dreams. He invites us to think of his film freely, imaginatively. That is why I based this comment on my free associations to the film, Bergman, the launching pad, therapy.

This is what Fellini is striving for, to judge from Irving Levine's 1965 interview with him: "In my films, what is constantly repeated is the attempt to suggest to . . . . modern man a road of inner liberation, of trying to accept and love life the way it is without idealizing it, without creating concepts about it, without projecting oneself into idealized images on a moral or ethical plane." In other words, just enjoy the movie, enjoy the story, enjoy the poem. How that would liberate my profession of literary criticism from its laborious, jargon-ridden "theory."

This is a film about how great it can be just to have images and sounds and experiences, particularly of sexy women. Why do you want themes? Abstractable meanings? Alas, I am altogether too Daumier-like just to relax and enjoy Fellini's fantasies. I need to make sense of things, to interpret. So I've come to a paradox, the essential contradiction one faces in writing about Fellini. We are to be playful, relaxed, accepting, but we also need to accept ourselves. For me that means accepting my need to make critical sense of Fellini's creative work, and I think that's a need most people who see this film share. We are who we are. Get used to it. I have to accept that I, another Daumier, cannot live up to Fellini's wise advice. My need to understand the film conflicts with my simple enjoyment, and I think that is probably true for you too. This paradoxical response shapes any thinking person's experience of this film. We need to accept that we are what we are, inquiring beings, and that we are going to stay that way. That 8½ can evoke such a painful, profound, and true paradox testifies to its status. It is, quite simply, one of the greatest films ever made.