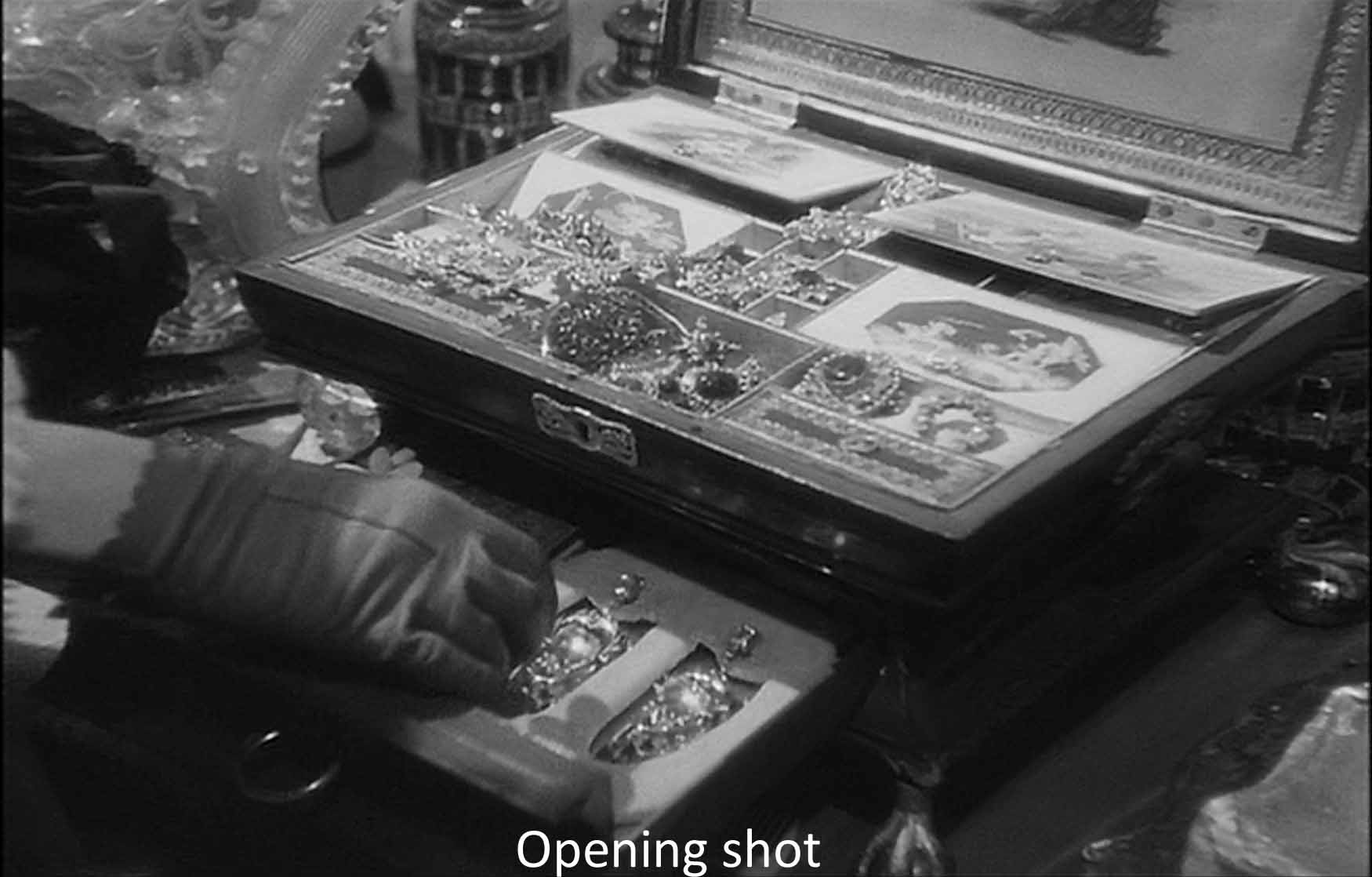

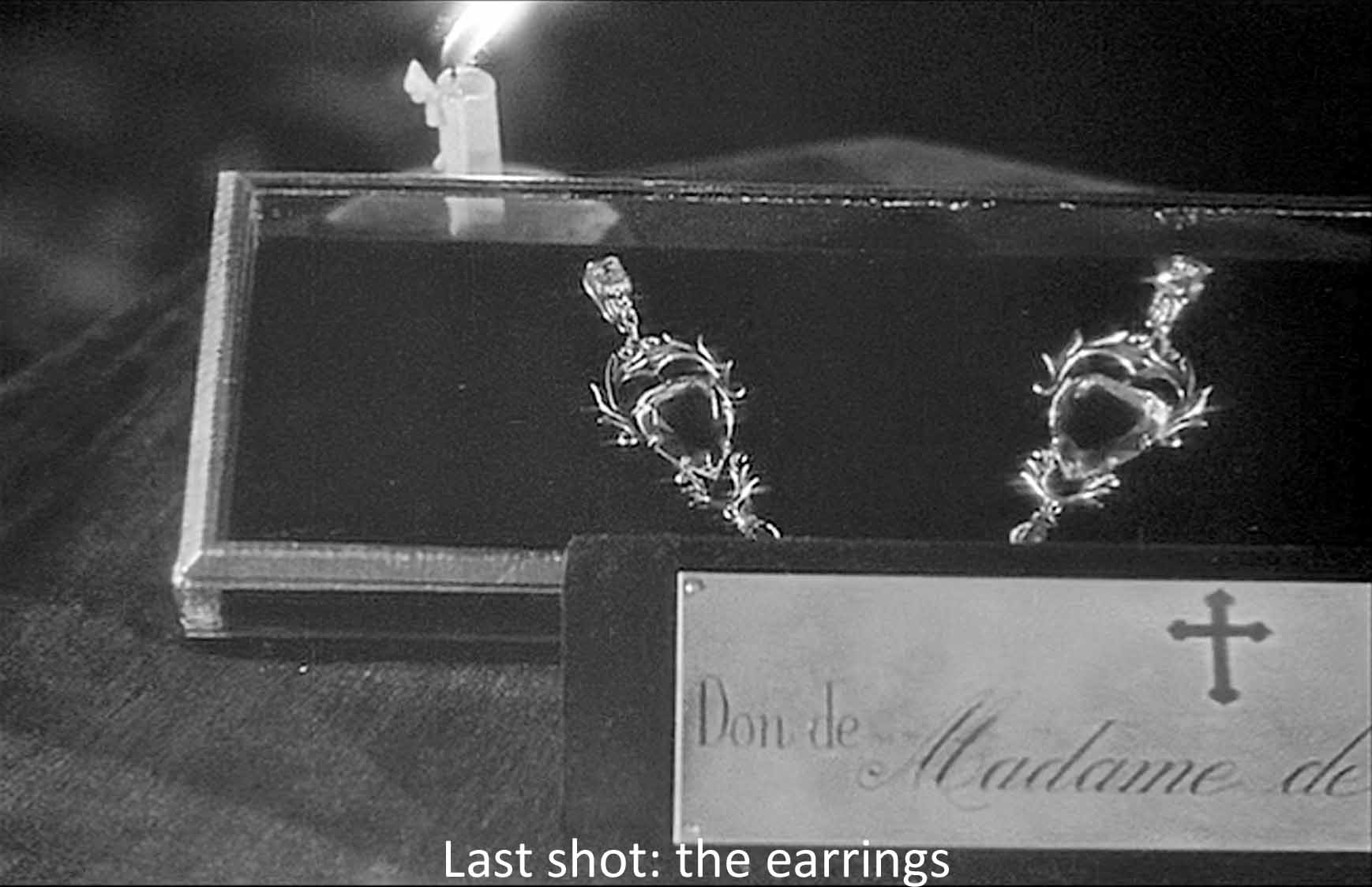

In this charming film, the travels of a pair of heart-shaped diamond earrings impel the plot: the husband (Charles Boyer) gives them to his wife; the wife (Danielle Darrieux) needs cash and sells them back to the jeweler; the jeweler sells them back to the husband; the husband gives them to his departing mistress; the mistress sells them in Constantinople; there an Italian diplomat (Vittorio de Sica) buys them and gives them to the wife with whom he has fallen in love; and on and on, until comedy becomes tragedy. Money, money, money, the earrings equal money on which this gorgeous society rests, and the glittering, hard hearts on which it relies.

The husband is “le Général,” an aristocrat. “André de . . .” ; the de, three dots or no, tells us his status, to say nothing of his upper-class bearing and tact and household. He looks forceful with his elaborate uniforms, his military posture, his irony and graceful condescension toward inferiors like the jeweler. He and his wife address each other with vous, the formal second person. The Italian diplomat, Baron Fabrizio Donati, shares André’s noblesse, but his body language is more flexible as befits a diplomat, his language less ironic as befits a lover, and he is more volatile and voluble as befits an Italian. He is open to passion in a way that would be unthinkable for the general. And Madame, Louise, is the very model of a turn-of-the-century grande dame, beautiful, flighty, manipulative, but chilly. We first see her face in a mirror, after seeing her hands touching, trying to choose among her furs and gowns and jewels. The many staircases these characters ascend and descend signify, I think, that all three rank in the highest strata of society. All three are on display.

The earrings thing sounds gimmicky, but not to some leading critics. Auteur theorist Andrew Sarris repeatedly called Madame de . . . , flat-out, “the greatest film of all time.” He quoted New York Times critic Dave Kehr as an ally, “Should the day ever come when movies are granted the same respect as the other arts, The Earrings of Madame de . . . will instantly be recognized as one of the most beautiful things ever created by human hands.” New Yorker critic Pauline Kael simply said, “Perfection.”

Let’s look at it. I see four forces at work, driving this plot.

One is chance, which the characters call le destin, destiny or fate with a capital F. Louise and Donati just happen to see each other in a customs office. Their carriages just happen to collide. (These incidents, by the way, Ophüls introduced; they are not in Louise de Vilmorin’s novel on which he based the film.) Donati just happened to be seated next to her at a state dinner. He just happened to be in Constantinople and happened to buy these particular earrings. And so on until, at the end of the film, the general takes command and orders events his way. No more chance. As the feminist critics point out, masculinity and patriarchy take control.

The fate idea touches on religion. Louise twice prays to St. Geneviève, the first time successfully, the second not. In the last shot we see that she has donated (or bequeathed?) the determining earrings to the altar of her saint. Religion or superstition? Her old nanny tells Louise’s fortune with cards, and sometimes she’s right. Either way, the female characters believe in an overarching, perhaps supernatural force at work.

Cooperating with le destin is a second force at work: the overwhelming passion Louise and Donati feel. Both fight it, but neither can resist it, though both realize how dangerous it is. The film starts with Louise’s money worries. It ends with her grande passion.

The great theme of French movies is humans in (or against) society. Here, Donati and Louise adorn society, but are imprisoned by it, too. In this exquisitely formal culture, passions are dangerous. Cool is what you need. This is the way the general describes his marriage to his wife in a last-ditch effort to get her to snap out of the depression she has been suffering since Donati left her: “Up until now, though I didn’t play a large part in your life, I was the only one. There was camaraderie, even gaiety, between us.” As for her depression, “I’m your friend. Let me help you.” Pallid words to describe his desperation at the threat to their marriage..

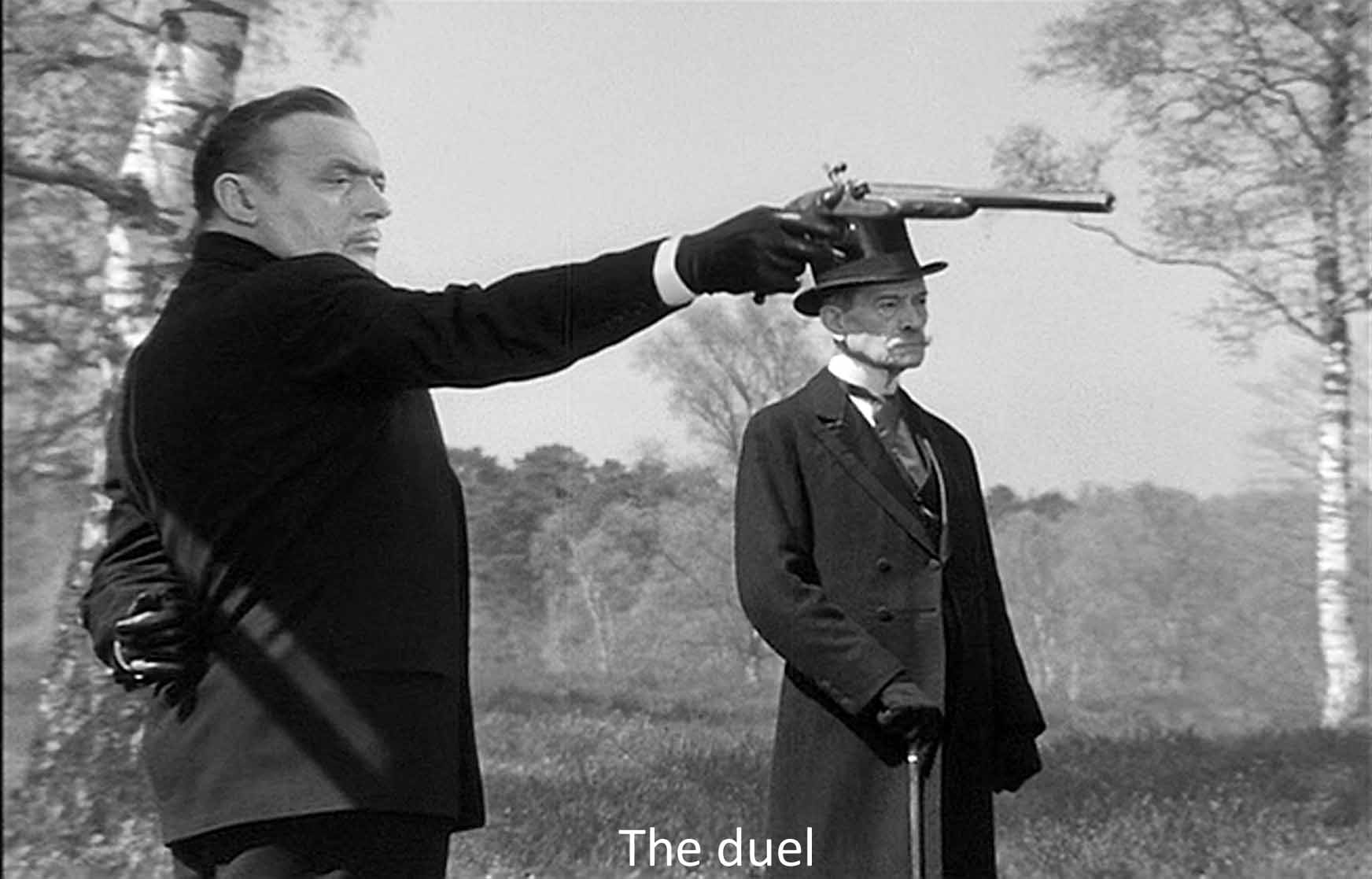

It’s at this point that he takes over, directing events, forcing an ending different from the novel’s. The general challenges Donati to a duel that the general will surely win. We see him at target practice, putting three shots in the heart on the target (echoing the heart-shaped earrings). Strong passions (like Donati’s, like Louise’s) are dangerous. They call down retaliation from the injured husband, representative of a masculinist society, a third force generating the plot.

Did the lovers have sex, justifying the general’s action? We do see one passionate embrace. But Louise says to Donati, “You, know we’ve given him no reason.” And, praying to Ste. Geneviève, “You know that we were guilty in thought only. And what are thoughts?” Would she lie to her lover or the saint?

I don’t think so, although she lies constantly to cover up the wanderings of those earrings. Her lies reveal her deceptions to André, and they eventually disgust Donati, leading to his dropping her and to her depression. Fate, passions, and patriarchy are three forces driving the action.

Lies are a fourth, and as such they raise one of the most interesting ideas prompted by this film. Lies—the question almost asks itself. Isn’t fiction itself a lie, an untruth? Isn’t this film? Just as Louise’s lying causes particular events in the plot, doesn’t the auteur’s lying impel the whole thing? That was a classic Puritan objection to fictions—they are lies—and probably one reason authors well into the eighteenth century assured their readers they were telling a true story. And even today, American Sniper’s credits in 2015 proclaim that it is “Based on a true story.”

But as Sir Philip Sidney famously answered, “Now for the poet, he nothing affirmeth, and therefore never lieth.” Ophüls isn’t claiming his story is true-or is he? There’s that curious trick in this film of the three dots after de in the title (”ellipsis” for the English teachers among us). By artfully concealing what comes after the aristocratic de whenever it is about to be revealed, Ophüls is pretending this is a real woman and André is a real husband, both of whose reputations and names need protection. The three dots suggest that this isn’t a fiction, but a true story.

Among other things, then, Ophüls is playing with the nature of art as, well, play. It doesn’t (usually) claim truth-value, but it shows in a make-believe situation truths, here, that true love can transform people, giving them a depth and solidity they lacked before. And true love is a threat to an excessively rigid society while flirtation is not. Early in the film André described Louise as an “incurable flirt.” In the best French manner, he dryly tolerates the men whom she “tortures by hope”; the Italian Donati is irritated by them. By the end of the film her love and her shame at betraying it by her lies have gained tragic weight. Sarris described the film as exploring “the transformation and transfiguration of an initially frivolous and flirtatious society woman into a tragic victim of romantic rapture.”

True, and the glamorously beautiful Darrieux makes that transformation visible in a great performance that takes her character from glamorous beauty to wretchedly depressed woman. One should mention, too, the portrayal of the general as cool, stiff, determined, and aristocratically ironic in the French tradition. Charles Boyer, arching his remarkably angled eyebrows, gives a splendid performance. So does Vittorio de Sica as the quite different Italian. Softer, flexible, passionate, sometimes bewildered by his situation, his body language contrasts neatly to the military bearing of the general.

Is this “the greatest film ever made”? I’m not sure I’d go so far, although it has amazing things like the circling dance sequence in which Louise and Donati fall in love. It combines weeks of time, space, manners, and art to re-create, like nothing else in movies, that extraordinary emotional moment. In scene after scene, Ophüls’ long tracking shots sweep up and down the many staircases, around the ballrooms, and, finally, the length of the dueling ground. He demonstrates throughout that he is a master of the moving camera and one of the truly great artists in film. This is one of his greatest films.