This is no ordinary wuxia film, that is, no ordinary action or martial arts film. That is, according to Ang Lee, “the most populist, if not popular, genre in film history.” “The drama is itself choreographed as a kind of martial art, while the fighting is never just kicking and punching, but is also a choreography in which the characters can express their unique situation and feelings.” Women warriors were crucial to the wuxia style in fiction and film. That is why this is a romantic drama, driven by sex, even if the fights were designed by the martial arts master Yuen Wo Ping who designed the fights for another amazing film, The Matrix (Wachowski Bros., 1999). Ang Lee says, “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, the hidden dragon is, to me, the repressed sexuality, you know. So I think that’s the emotional truth to Chinese psychology.”

Ang Lee builds his film around two pairs of lovers (from an early twentieth-century novel that innovated by mingling romance into martial arts fiction). Instead of the thumps and bangs of the conventional martial arts film, Lee creates a romantic, ethereal movie with more flying in it than impacts. At the beginning, sixteen minutes elapse before we get the first fight. That’s not like the usual Hong Kong martial arts film which starts off with a literal bang.

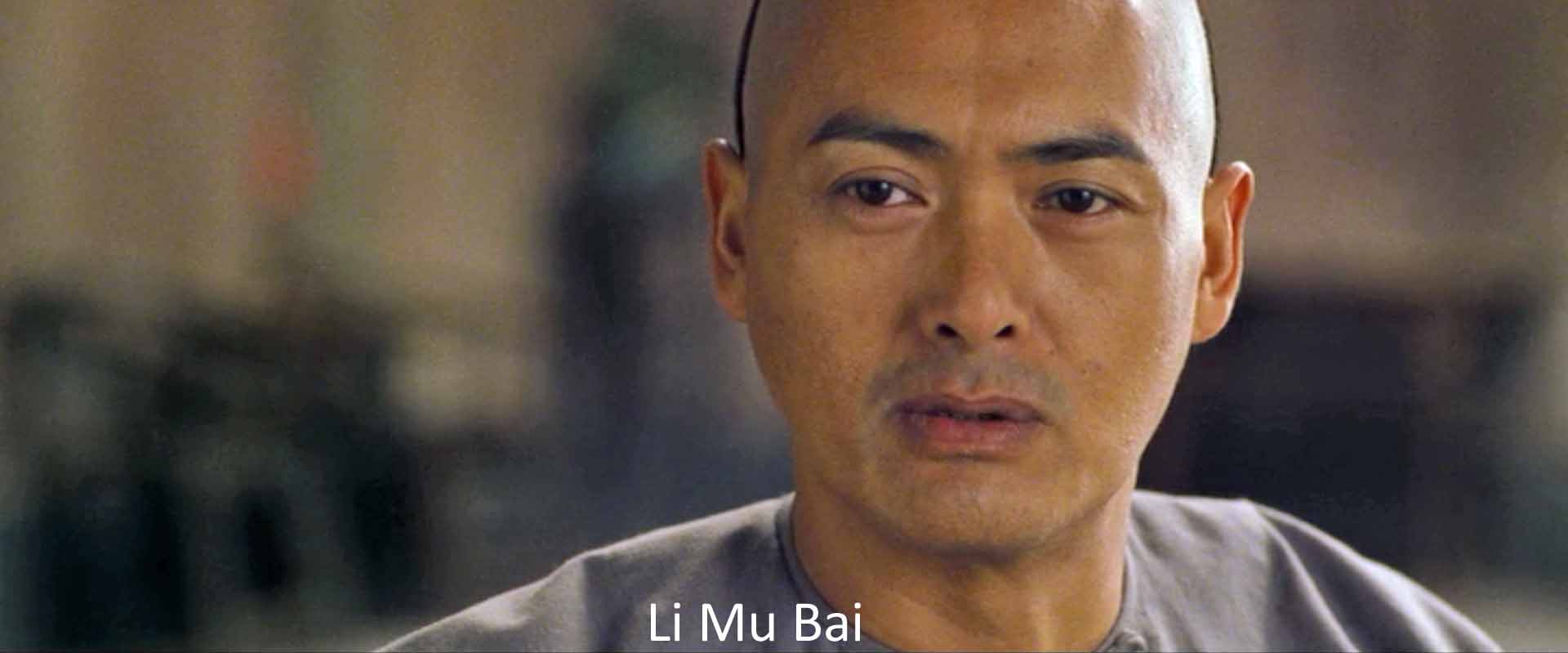

One of Ang Lee’s pairs of lovers is thirtyish, the other quite young. The older pair includes Li Mu Bai (played by the popular action film star, Chow Yun Fat). He has come to see Yu Shu Lien (another famous action film star, Michelle Yeoh). She is a warrior who heads a security company in the business of guarding commercial shipments. The older pair, Li Mu Bai and Yu Shu Lien, have loved each other for years but have been unable to express that love, much inhibited by traditional codes of decorum and modesty. Both are famous fighters in the world of jianghu,

The word means “rivers and lakes,” and it refers to an underworld of wandering outlaws in which traditional martial arts stories take place. A knight-errant tradition began in China in the fourth century B.C.E. and became a fictional genre in the Tang dynasty in the ninth century C.E. These stories flourished in the seventeenth century C.E. and later, culminating in the wuxia pian or martial arts films from the 1920s on. Fighters in these films are a bit like Robin Hood. They have a code of honor and go here or there fixing injustices. They also challenge one another as the young heroine of this film challenges the people she meets. To me, the world of jianghu and wuxia is quite like the King Arthur stories in Malory’s Morte d’Arthur (1485) with knights roaming about, following a chivalric code, but challenging any other knights they meet just for the heck of it.

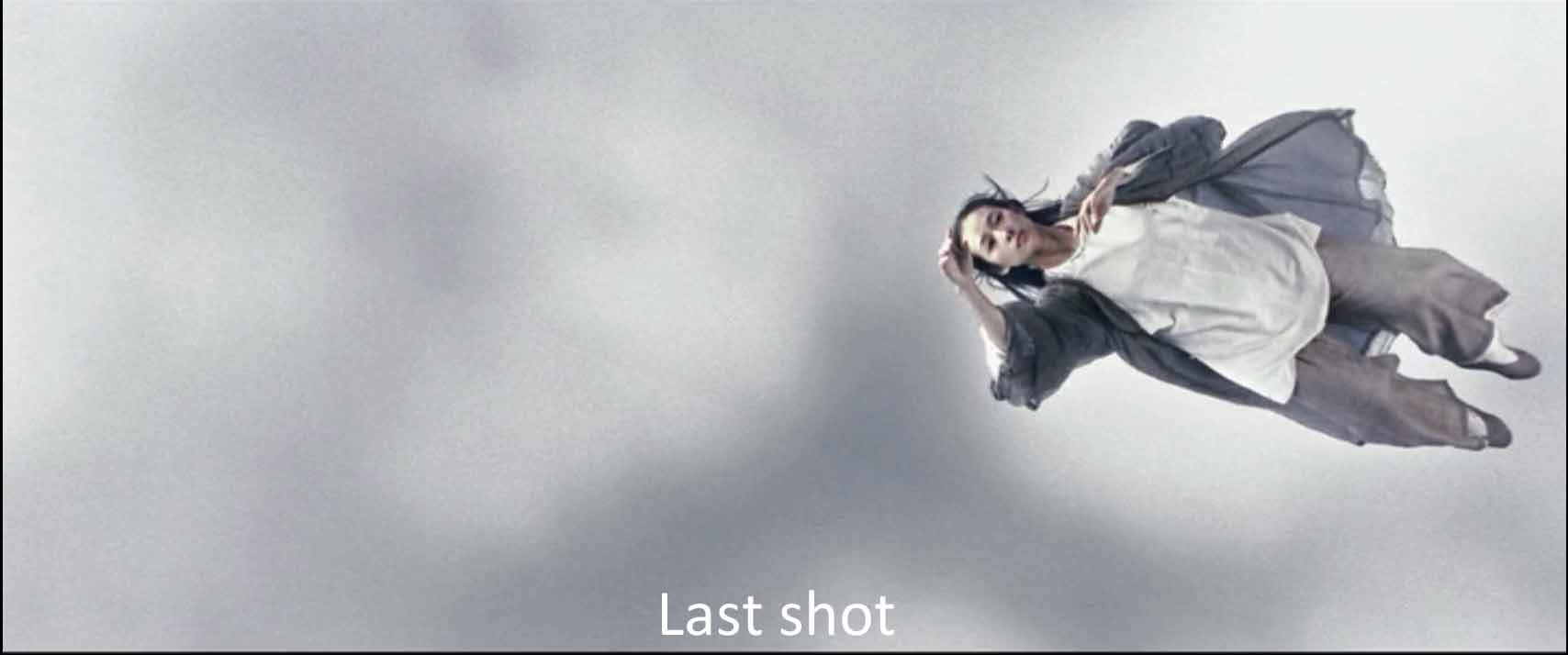

The younger pair consists of a beautiful young aristocrat, Yu Jiaolong (Zhang Ziyi, who went on to star in many mainland films) and Luo Xiaohu (Chang Chen). He is an outlaw who (in a flashback) raided her elaborate caravan (a contrast with the shipments Shu Lien guards). He stole her treasured jade comb, and she chased him to get it back. With fighting as foreplay, they became lovers. Where the older couple follows decorum, these two flaunt their lack of inhibition. He is a bandit given to bold exploits. She is hugely talented in martial arts, but she lies, steals, fights, kills, and has sex with this bandit. Visually, she flies upward again and again as if to suggest her rising above ordinary rules.

Mandarin-speaking critics complain of the subtitlers who call these two Jen and Lo. The girl’s full name means “winsome dragon” and the boy’s “little tiger.” These obviously refer to the title of the film, as critic Pauline Chen explains:

The significance of the film’s title, which is a Chinese idiom referring to hidden or unsuspected forces or powers, is glossed in a key line spoken by Li to Shu Lien . . . . “In jianghu there are crouching tigers and hidden dragons, just as there are in men’s hearts. Blades and swords conceal evil, just as men’s emotions do,” he reflects . . . This line is translated in the subtitles simply as, “Giang Hu [sic] is a world of dragons full of corruption,” which inadequately conveys the original insight on how internal conflicts, unacknowledged desires, and impulses for destruction and betrayal hamstring the characters’ pursuit of the love and happiness they purport to want.

Wikipedia adds that the title comes from a poem by the ancient Chinese poet Yu Xin (513-581). It translates as, “Behind the rock in the dark probably hides a tiger, and the coiling giant root resembles a crouching dragon.”

The young heroine’s name is Jen Yu (in Mandarin) and Jiao Long (in the dubbed English version). The last character in her name means “dragon.” Lo (Mandarin) or Luo Xiao Hu—the last character in the bandit’s name means “tiger.” The point of their names is, I take it, that it is their emotions, their lack of inhibition, that mostly drives the film. Even so, for simplicity’s sake, I’ll call the younger couple Jen and Lo to match the subtitles such as they are. Alas, as if to confuse matters, Jen’s mother is called “Madame Yu,” confusing her with Yu Shu Lien (whom the subtitles sometimes call Yu).

We probably should not complain of the subtitlers. They faced an impossible job, for the Mandarin characters that the actors were speaking have roots that are millennia old. “The Chinese embedded in every word of this movie,” says its co-writer James Schamus, “has layers and layers of culture and meanings. They simply don’t exist to a Western ear. It is one of the truly delicious ironies of this movie that although I co-wrote it, I’ll never fully understand all of its meanings.” We need to do as well as we can with the subtitles and enjoy the visuals.

The film begins as Li Bai returns to Yu Shu Lien and her security firm. This is the world of commerce and combat and jianghu that Li Bai had temporarily given up to seek deeper, more mystical training at the Wudan monastery. Roger Ebert comments in his review of this film: “The best martial arts movies have nothing to do with fighting and everything to do with personal excellence. Their heroes transcend space, gravity, the limitations of the body and the fears of the mind.” In other words, when the characters show off their amazing martial skills, they are really showing off their amazing mental discipline.

These fighters, good and bad, glory in their almost supernatural powers that surpass ordinary humanity. But in the beginning we have not yet seen this transcendence. Li Bai gave up his meditation training because something was pulling him back—and we may surmise it is both his need to avenge his murdered master and his love for Shu Lien that he cannot express, a crouching tiger, a hidden dragon. He wants to give up the world of jianghu and, with it, his invincible sword Green Destiny. He asks Yu to take it to Peking and give it to Sir Te (Sihung Lung, the father-figure in Lee’s first three films).

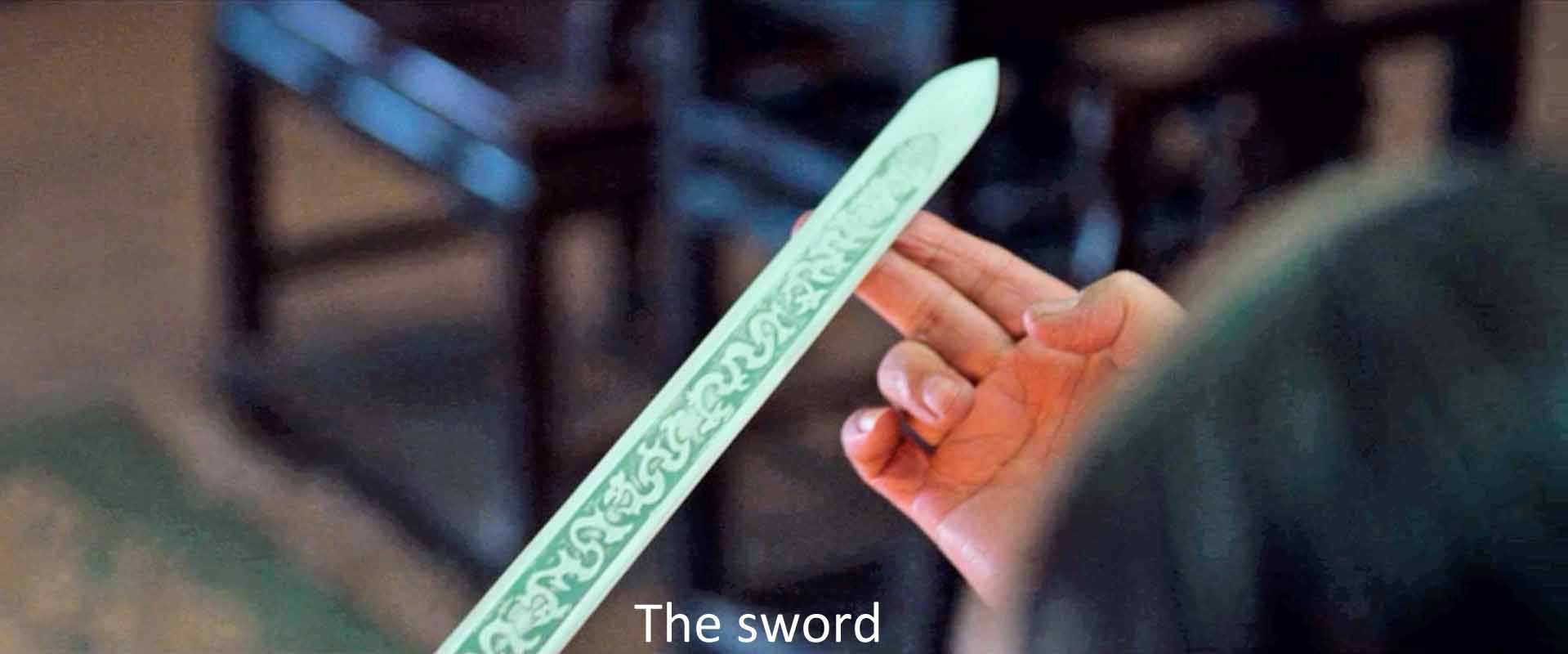

Something of a mentor, Sir Te urges them to express their love. “When it comes to emotions, even great heroes can be idiots.” Shu Lien delivers the sword, but demonstrates it to Jen. Though a governor’s daughter, an aristocrat, Jen longs to be a warrior like Shu Lien and Li Bai, “totally free.” But Shu Lien demurs. “Fighters have rules too: friendship, trust, integrity . . . Without rules, we wouldn’t survive for long.” But Jen doesn’t give a damn for rules. She steals the sword and maintains her theft by a dazzling display of skills.

The sword is an obvious phallic symbol, substituting for real sex between Li Bai and Yu Shu Lien, but illicitly enjoyed by Jen. Four hundred years old, amazingly carved, and flexible as a whip, every time it appears on screen there is a magical whir. It stands for the nobility of the true warrior, Li Bai, who has tried to perfect himself in the manner of Tao mysticism at the Wudan monastery.

In this film knowledge is power, and teaching is precious. (Echoes of Ang Lee’s “father knows best” trilogy.) The master-student relationship runs all through this film. In the background, there was Meng, now dead, Li Bai’s master, who was engaged to Yu Shu Lien. That is why she feels custom does not allow her to give herself to Li Bai. Meng was killed by the villain of this film, Jade Fox (Pei-pei Cheng), and Li Bai is duty-bound to revenge his murder and kill her before he can give up his jianghu life and the magical sword Green Destiny. Contrasted to the decorous Li Bai and Shu Lien are the totally indecorous, untaught Lo and self-taught Jen. Li Bai himself sees great but undisciplined potential in Jen, and he wants to become her teacher so as to perfect her skills as a martial artist. The core question of the film is, whom will Jen take as a master noble, Li Bai or evil Jade Fox?

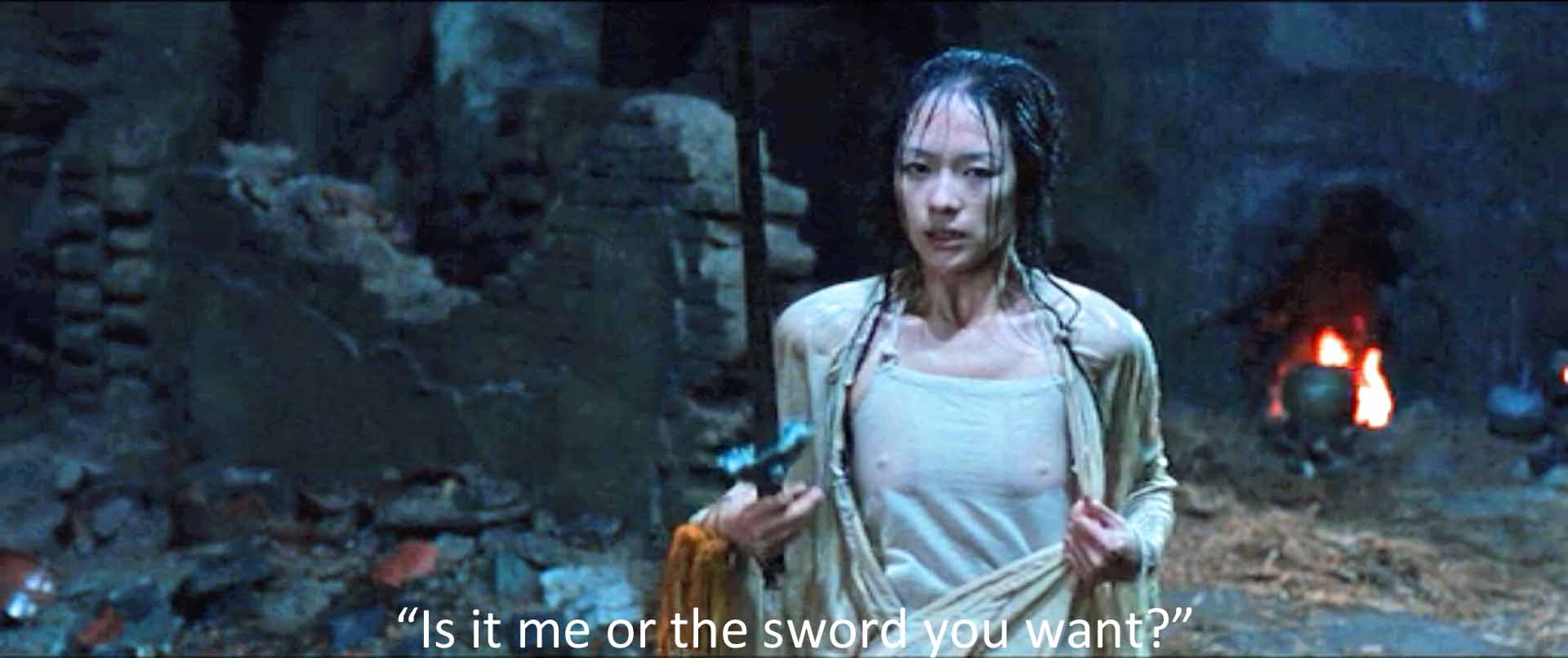

But the master-student relation has gone awry. Rather than secure Confucian decorum, it has proved disruptive. The original act that turned Jade Fox into a villain was her Wudan master’s taking advantage of the master-student relation to have sex with her. Ever since then she has harbored a rage with which she has infected Jen who in turn inflicts it on Li and Jien. Jade Fox uses poison, potions and poisoned arrows, and that is completely contrary to the martial arts code. Poison symbolizes her corruption. But even Li Bai is sexually tempted. He keeps telling Jen that he wants to teach her so that she can perfect her remarkable powers. Just give the sword back. But Jen (in a wet t-shirt) asks him, “Is it the sword you want or me?”

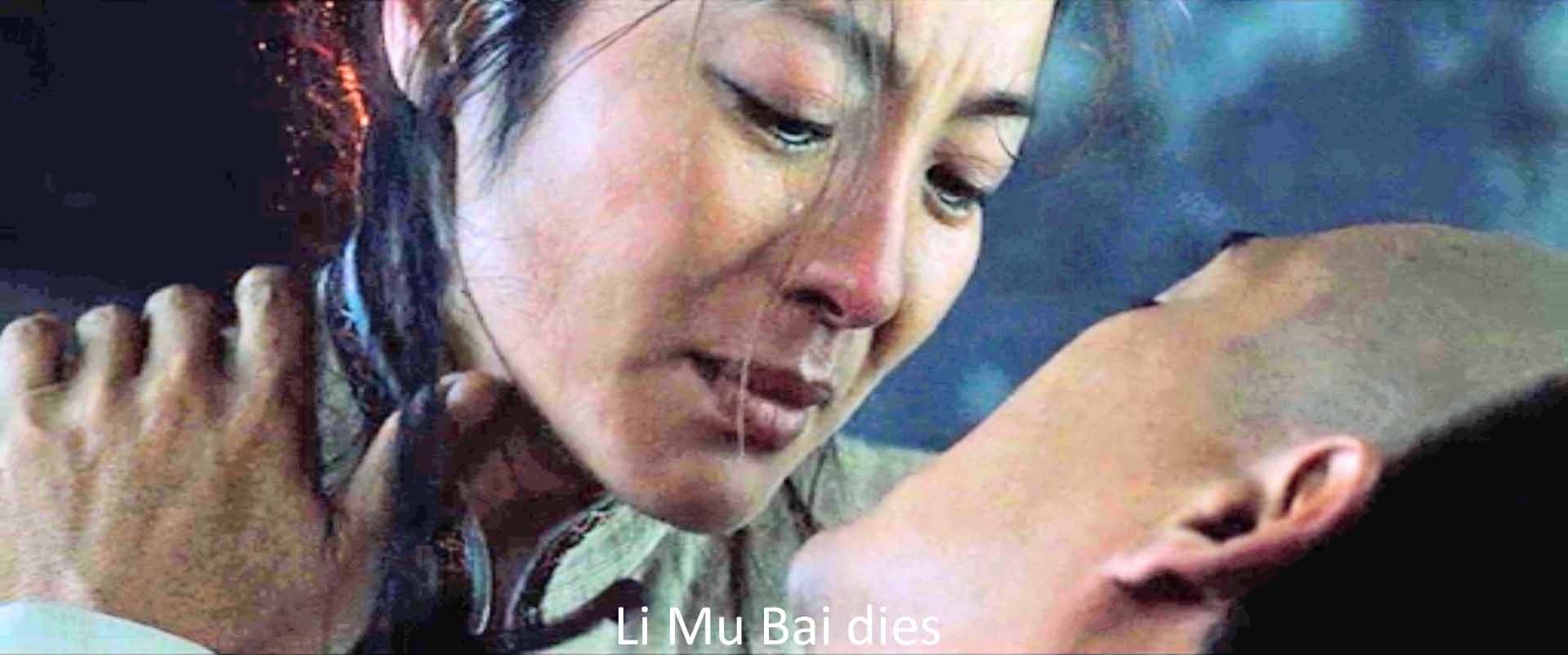

In short, for all that this is a martial arts movie, it is acknowledged and unacknowledged sexual desire that drives the plot, both the explicit sex of Lo and Jen (unusual for a Chinese movie) and the suppressed sex of Li Bai and Shu Jien. In the back story, predatory sex motivates Jade Fox. In the opening, sexual desire keeps Li from perfecting his meditation and fighting skills at the Wudan monastery. And at the end it is sexual desire that leads Jen to take her final leap, whatever it signifies.

Like all good art movies, Crouching Tiger is open-ended. Jen jumps off a high cliff, and we last see her floating among clouds. No Hollywood happy ending here. Is she going transcendently up or calamitously down? She is following a legend told by Lo about a son on this mountain with desperately ill parents. He wished for their recovery, and, “He jumped. He didn’t die. He wasn’t even hurt. He floated away, far away, never to return.” “A faithful heart makes wishes come true.” What does Jen’s jump imply? What wish is she hoping to gratify? Li Bai’s recovery? Reunion with Lo? Training for herself? There are several possibilities. Perhaps she dies to liberate herself, rather than marry and sustain tradition. Or she sacrifices herself to the Confucian values of order, authority, and obligation. Or she sacrifices herself, but she finds fulfillment in sacrifice. Or her death serves to give the film the resonance of classical tragedy. And I am sure there are other possibilities. If we are a good art film audience, we won’t try to choose among them.

Instead we will re-enjoy the extraordinary balletic fights among the characters, the sage and steady Li Bai, rash Lo, thoughtful Shu Lien, and flighty Jen. They are accompanied by extraordinary music: created by the well-known composer Tan Dun and, the cello solos at least, played by Yo-Yo Ma. We will recognize that the fights not only offer spectacular visual and aural effects, but demonstrate character and, above all, the Confucian values that Ang Lee wanted to offer the West, values identified, interestingly, as li, order, decorum, restraint, responsibility.

Anthony Lane has made the intriguing suggestion it may be Asian directors who will rescue current American film from its lame aesthetic of comic-book movies, rom-coms, and teen saviors of humanity. Perhaps we can look to directors like Ang Lee, Hou Hsaio Hsien, Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige, Takeshi Kitano, or Apichatpong Weerasethakul to resuscitate perennially sick Hollywood. Perhaps we can look to Asian talent as in the 1930s and ‘40s we turned to the European talent that had fled Hitler, people like Ernst Lubitsch, Michael Curtiz, Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, or Fred Zinnemann.

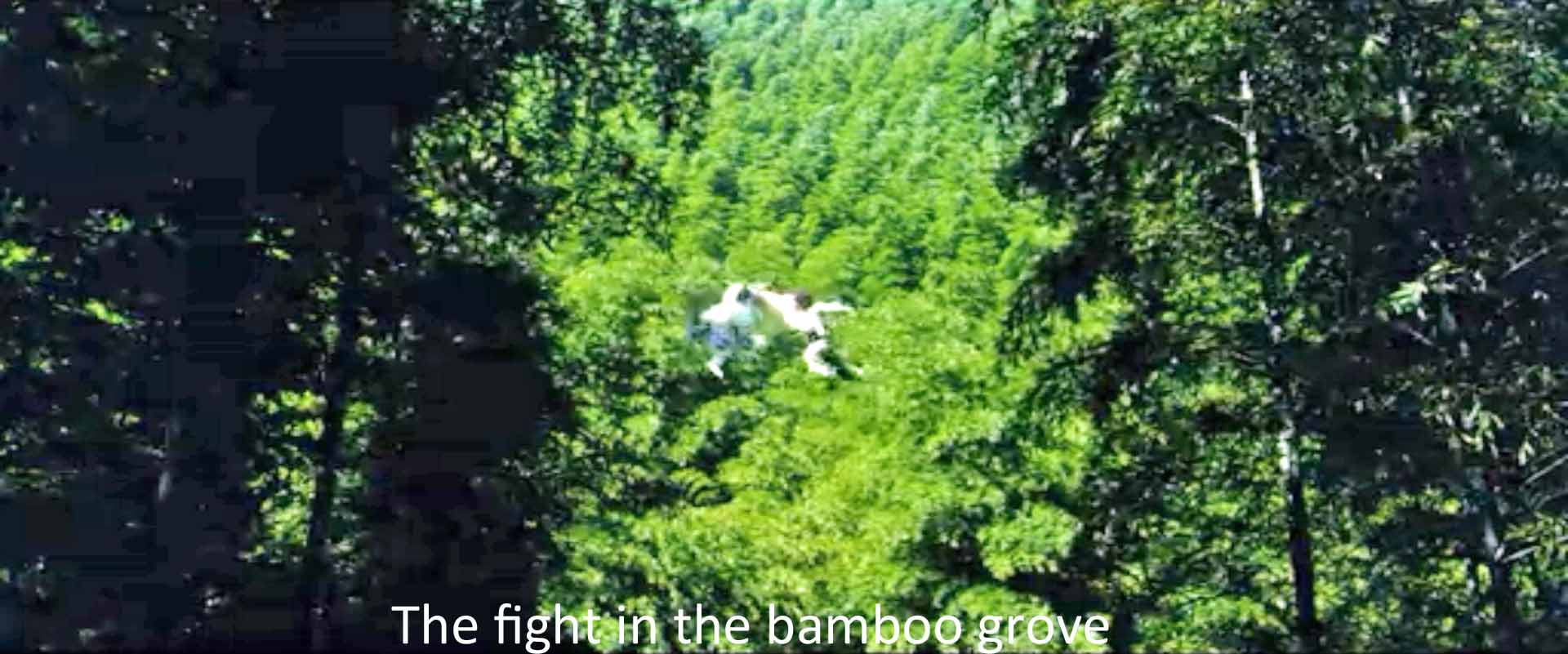

Be that as it may, in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Ang Lee has created a remarkably beautiful and inventive film with extraordinary scenes like the fight in the bamboo grove and “flying” up walls and across water. Yet even in these exaggerated actions, the actors’ faces convey thoughts and emotions that transcend the stunts. Not so much their voices, for Mandarin is a tonal language that restricts the raising and lowering of the voice.

Predictably, when Lee made a film that presented Chinese values to the West, he was accused of “orientalism.” That is, some critics claimed that he took a patronizing and essentializing attitude toward Chinese culture, packaging it for the West by portraying it as static, undeveloped, and something to be viewed for artistic pleasure, but not something to be seen as having value equal to the culture of Western colonizers. I think this is a knee-jerk reaction and unfair. Lee has written that he wanted to direct a martial arts film out of “nostalgia for classical China. The greatest appeal of the kung-fu world lies in its abstractions. It is a conceptual world based on ‘imaginary China.’ This world does not exist in reality and is therefore free from its constraints.” Think of the “flyings” or that extraordinary and quite impossible fight at the tops of the bamboo trees. Given such a purely fictional and aesthetic world, Lee’s point is simply that Confucian values are worthwhile and to be imagined and emulated. He wants to bring those values to the West, and he has succeeded. The box-office success of this film should be cause for admiration among Chinese, not regret. This is a film that we Westerners can learn from and admire. It is quite simply a great film.