As always, the opening shot has much to tell us, and Godard tells us what it is saying in the quotation with which he ends the scene: “‘The cinema,’ said André Bazin, ‘substitutes for our gaze a world more in harmony with our desires.’” But, as several critics have pointed out, this is not by Bazin, who was a favorite of the Cahiers critics like Godard, but by one Michel Mourlet. Bazin being one of Godard’s mentors, he would not lightly argue with him, but this other fellow? I think the rest of the film is designed to contradict this statement.

I think Contempt shows how cinema—and people—misunderstand and so frustrate desires. Godard has already done that. The opening shot shows a camera and cameraman taking a long tracking shot of pretty Giorgia Moll (who plays translator Francesca Vanini in the film to follow). She is walking along, reading some kind of booklet—the script of this film perhaps. I would like to see more of her; I’d like to know what she’s reading. This film denies me both. During her walk a voice over gives us the credits for the film, not written out so that I can see them, but spoken. Finally Raoul Coutard, the immensely talented cinematographer for this film, swings his camera round and focuses on me, us, the audience. We might like to see what he filmed, but we never do. Frustration.

The scene that follows the pseudo-Bazin quotation also frustrates our desires. It shows Brigitte Bardot (playing wife Camille Laval) nude on a bed with her husband, screenwriter Paul Laval (Michel Piccoli). Godard put this scene in at the insistence of the American producer Joe Levine, known for producing and distributing Hercules and Godzilla, King of the Monsters!. Levine complained that he was spending all this money, five million francs, to get Bardot into the picture, and he wasn’t getting any of what she was famous for, namely, nudity. So Godard obliged with this three-plus minutes nude scene. But he filmed her beautiful body through, first, a red filter, then natural light, then a blue filter. He de-eroticizes her. We (and Joe Levine) can’t really enjoy her nudity.

By his filters, Godard denies us the customary illusion that we are seeing real people and forces us to accept that this is “just a movie.” In the same vein, Bardot as the biggest European star of the time never stops being Bardot. Red and blue, by the way, will recur throughout the film, red the color of desire, blue the color of no-desire.

As the density of these first few minutes of the film might suggest, the film as a whole is thick with ideas and themes. Some deal with Godard’s constant subject, cinema. Paul Laval is a writer of detective stories and would-be playwright, but producer Jerry Prokosch (Jack Palance) has brought him in to rewrite the script for the film he is making of the Odyssey. He had first brought in the great German/Hollywood director Fritz Lang (played by himself). Lang plans a very classical (and static) film with lots of Greek statues that takes the Odyssey literally. Jerry who is probably a caricature of Joe Levine, wants a film with lots of sex in which Penelope is unfaithful. Paul is caught in the middle. He needs the money to pay for an apartment Camille wants (or may not), but he is not sure about Jerry’s ideas. And to make matters still more uncomfortable, Jerry is coming on to his wife.

In other words, the film plays with a whole series of desires that are frustrated. Paul wants money from Prokosch and love from his wife. Lang wants to make a “straight” Odyssey film, but his rushes are dull and static; Jerry hates them. Camille would like to love Paul, but is troubled by what she thinks he is doing. Jerry would like to make a blockbuster, but he doesn’t. In other words, film does not give us a world that accords with our desires. Film, real film, Godardian film, frustrates our desires and those of the characters, pace Bazin/Mourlet. Godard has always claimed he makes essays, not films, and desire defeated is one point of his essay here.

The film proceeds in the best Godardian manner by a series of long discussions. The first deals with the future of cinema, prompted by producer Jerry’s magnificent entrance. As in a Roman theater, he strides through giant doors. He orates about the empty buildings of Cinecittà, empty because yesterday he fired everybody. Now he proclaims, “Only yesterday there were kings here, and queens, liars and lovers, all kinds of real human beings.” And he is the master of all of them.

Jerry’s godlike entrance sets up the basic parallelism of the picture, between the Odyssey and filmmaking. The producer is to director and writer as the gods are to humans, and specifically as Poseidon is to Odysseus. (it is one of the boorish aspects of Prokosch’s film that it uses the Roman names for the characters although the Odyssey is in Greek. I’ll stick to the Greek.) Jerry gets his godlike pronouncements from a little red book like Chairman Mao’s, another man-deity. While he views Fritz Lang’s dailies showing a council of the gods, Jerry responds, “I like gods! . . . I know exactly how they feel.”

A god-image recurs: a statue of Poseidon hurling a now-lost trident, sometimes staring down at Paul who stands for Odysseus in Contempt. There is a back story to Poseidon’s feud with Odysseus. The hero, in order to save his crew from the man-eating Cyclops Polyphemus, burned out the giant’s one eye. Then, fleeing, he hurled insults at the now-helpless giant. Polyphemus was Poseidon’s son, and it was the insults, the loss of honor, that got to the god. He was forbidden to kill Odysseus, but he could torment him, and he did, afflicting him with various perils and temptations so that it took ten years for him to reach wife and home. I think the one-eyed monster is the huge camera that we saw in the opening scene, staring at us and Prokosch/Palance is, heaven help us, the god. Incidentally, Poseidon was the god of horses, and Jerry has lots of horsepower in his bright red roaring Alfa-Romeo 2600, an emblem of phallic power if there ever was one.

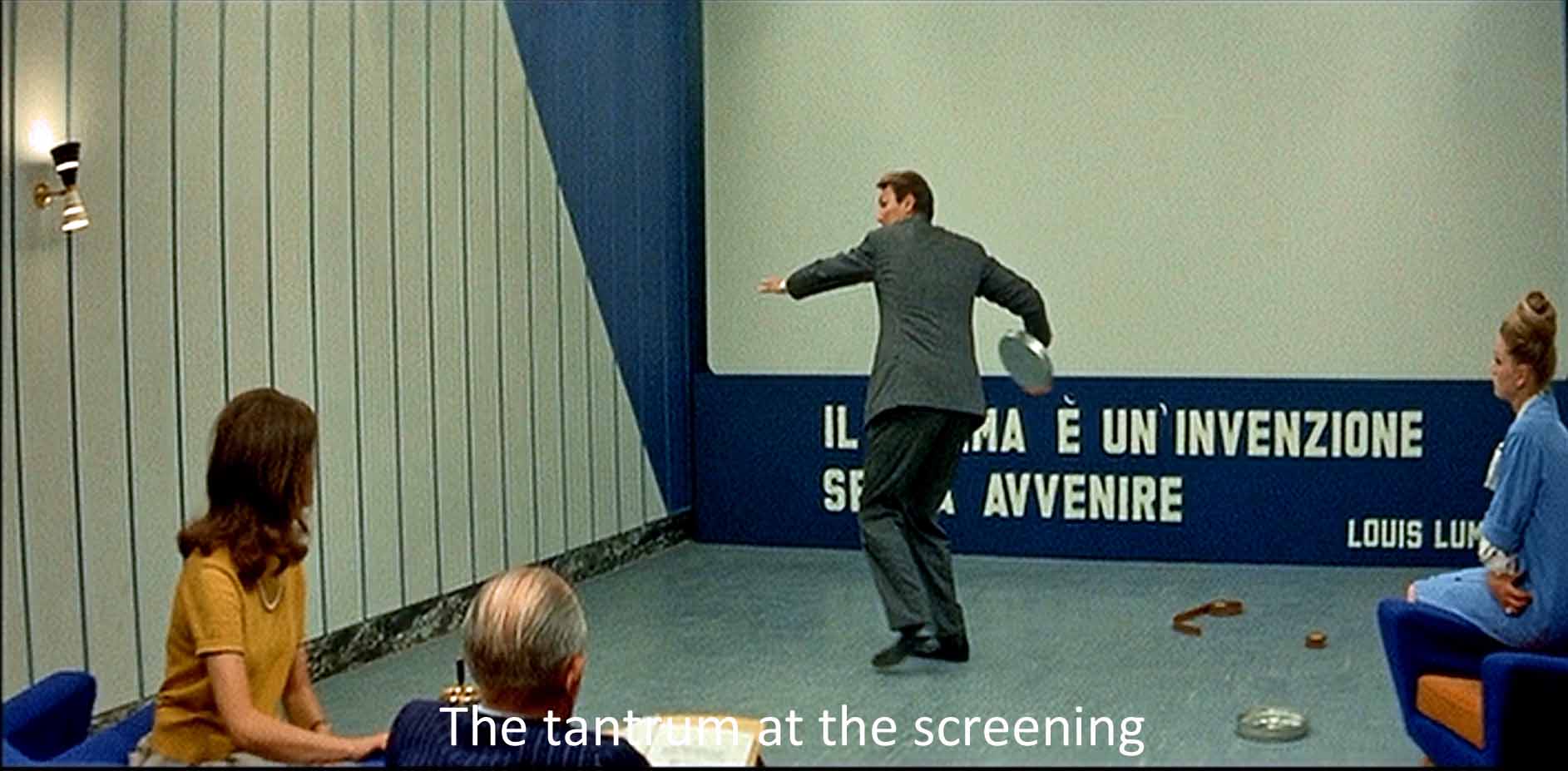

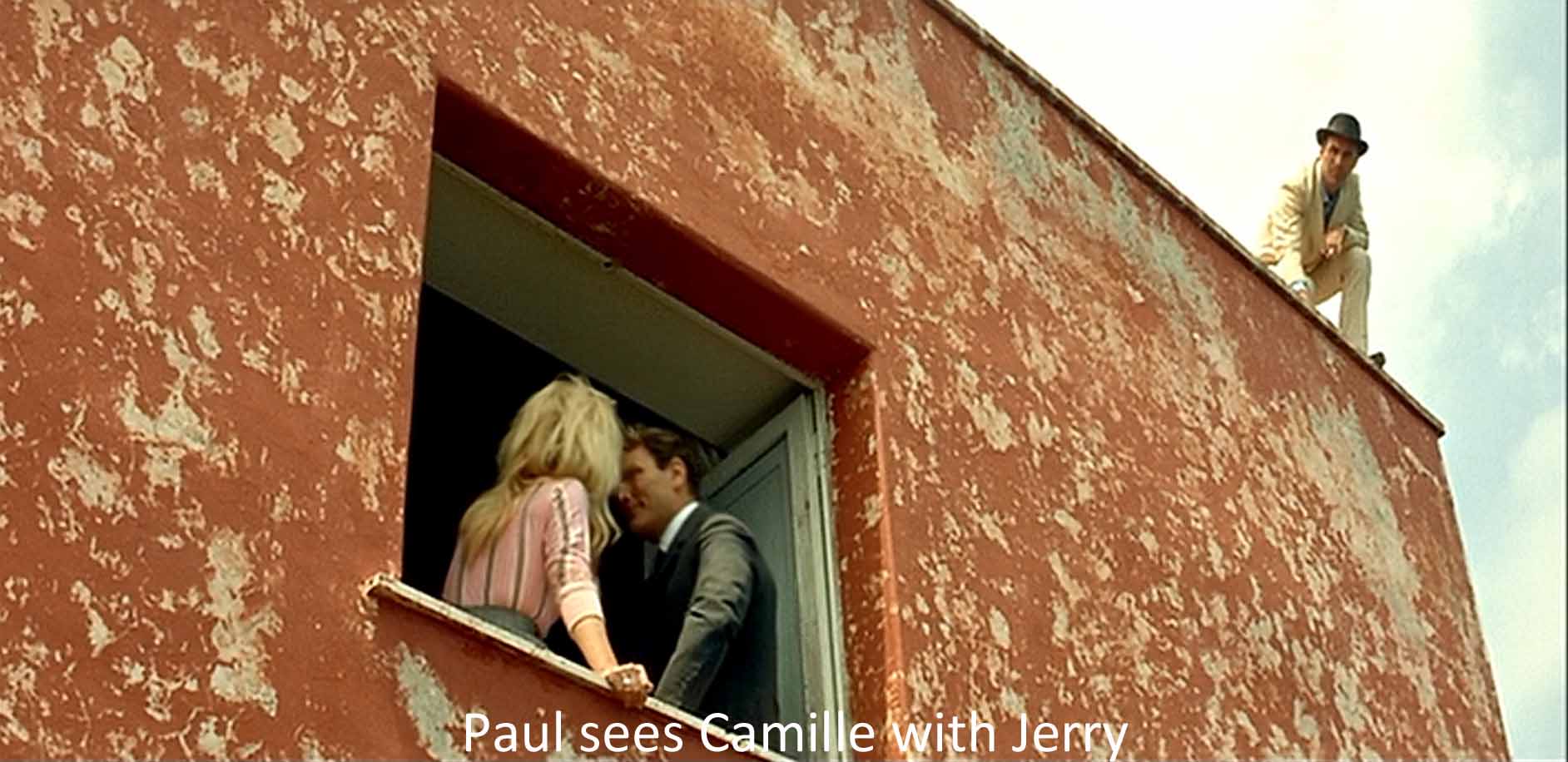

Jerry throws a tantrum after watching Lang’s rushes, and that leads to some discussion of the Odyssey and the perhaps hiring of Paul to rewrite the plot according to Jerry’s ideas. Jerry tells the group to come to his villa and, in a key moment, Paul urges a reluctant Camille to ride in Jerry’s sports car. He himself arrives at the villa a half hour later, leading to Camille’s idea that Paul is pimping her to Jerry to get money—salary. Is this why he bears the last name of the prime minister during the Vichy regime, executed as a traitor?

Paul and Camille return to their apartment. In a tangled 31-minute conversation done in long takes, in which Paul and Camille drift through the flat, undressing and dressing, getting into and out of a bath, wearing towels like togas, telling stories, lying. At one point Bardot dons a black wig that makes her look like Anna Karina, Godard’s then-wife with whom he was having difficulties. The film has turned autobiographical in the best postmodern tradition. Paul as Odysseus/Ulysses moves constantly and never “hangs his hat” anywhere except in the opening love scene. His hat signals that he is the wanderer.

In the long takes of the 31-minute scene, each tries to understand what the other desires. Do you really want the apartment? Do you want to go to Capri? Do you want me to take this job? Do you want me to get sexy with Jerry? Husband and wife both fail. Camille challenges Paul’s submissiveness to Prokosch: “You are not a man.” They quarrel until the marriage finally falls apart with Camille saying, “Je te mépris” [I feel contempt for you] and “I no longer love you.” And this is the ultimate frustration Godard hands us: we never really know why the marriage breaks up; it just does.

I don’t believe there are such things as spoilers, but I know that most people do. OK. I won’t tell you the ending—just that it contradicts (yet again!) Lang, his idea that “violence solves nothing.” It brings this puzzling movie to a definite end.

The final scene shows us Lang filming, the only character who seems about to satisfy his desire. Godard in a possible tribute to a master serves as his Assistant Director. He wears a hat like Paul’s. Echoing the opening shot, the camera dollies to follow a sidestepping Ulysses looking out to sea. (Lang is faking the rocking of a boat.) Godard shouts the final word: Silencio!, and the screen fills with blue sea—the end of words and deviousness and defeated desire.

The film has lots of other themes. The European characters quote all kinds of works of art: Dante’s Divine Comedy, poems of Hölderlin, “B.B.” (Brecht, but with a hidden reference to Brigitte Bardot). They know films: Lang’s Rancho Notorious and M; other films: Hatari, Rio Bravo, Viaggio in Italia. All this culture is what makes Lang, the director, the real artist (but old-fashioned!) and wordsmiths Paul and Francesca intellectuals but mere wage slaves. The producer Jerry is god, king, tyrant, dictator, even though his words come from a tiny red book. The Europeans have languages and cultures as opposed to brutish Jerry, but Jerry gets what he wants.