This is the fifth in Éric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales, and once again he and we focus on a smug, self-satisfied, and ultimately self-deceived man. Our hero is Jérôme (Jean-Claude Brialy, one of the stars of la nouvelle vague). In the opening sequence he tells us he no longer chases girls, for he, pushing forty, is about to get married in Sweden. But chasing girls is all he does in this film. And talk about it endlessly, since he is a Rohmer hero. For all that, he is quite mistaken about the teenage girls he pursues.

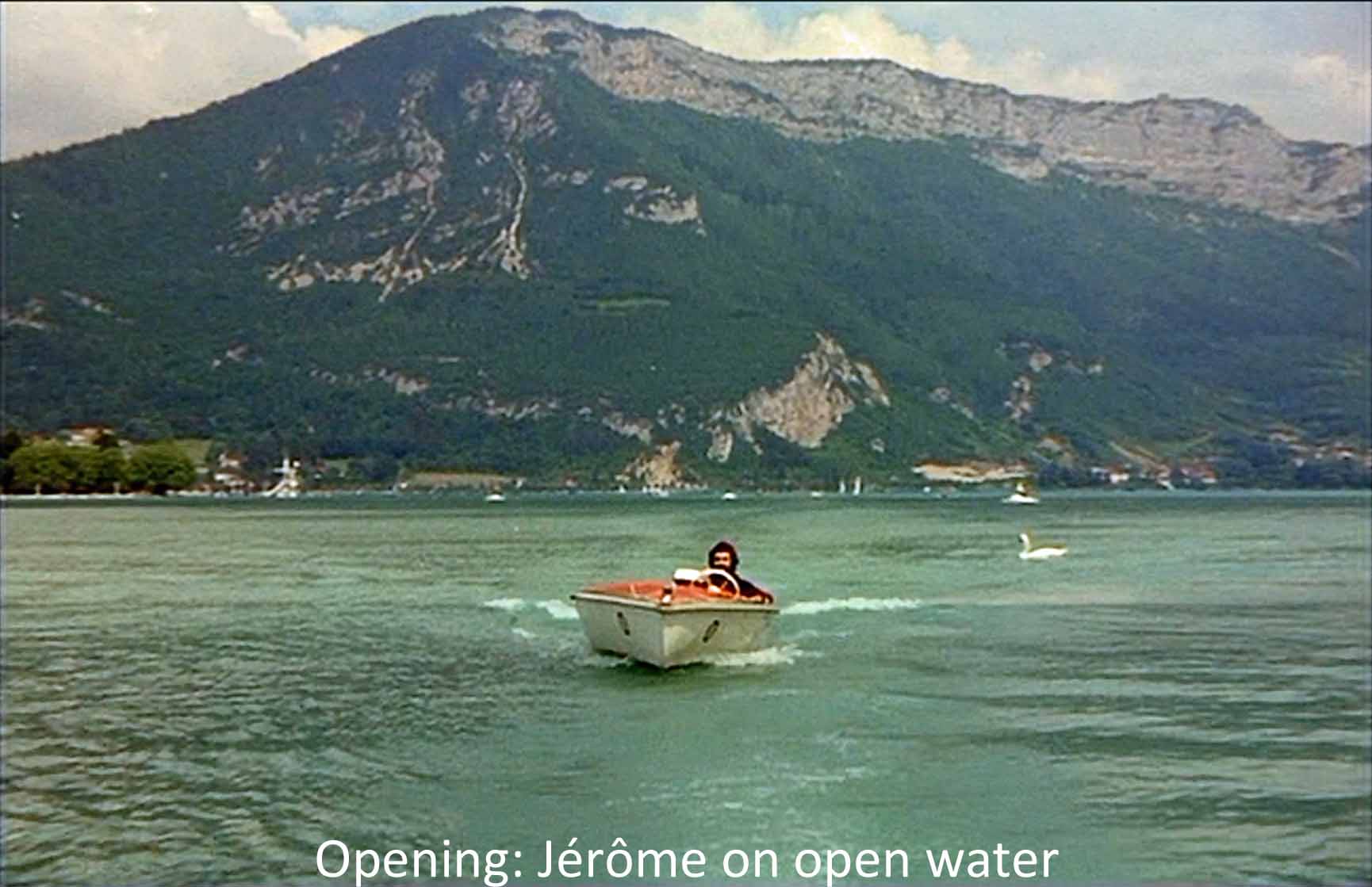

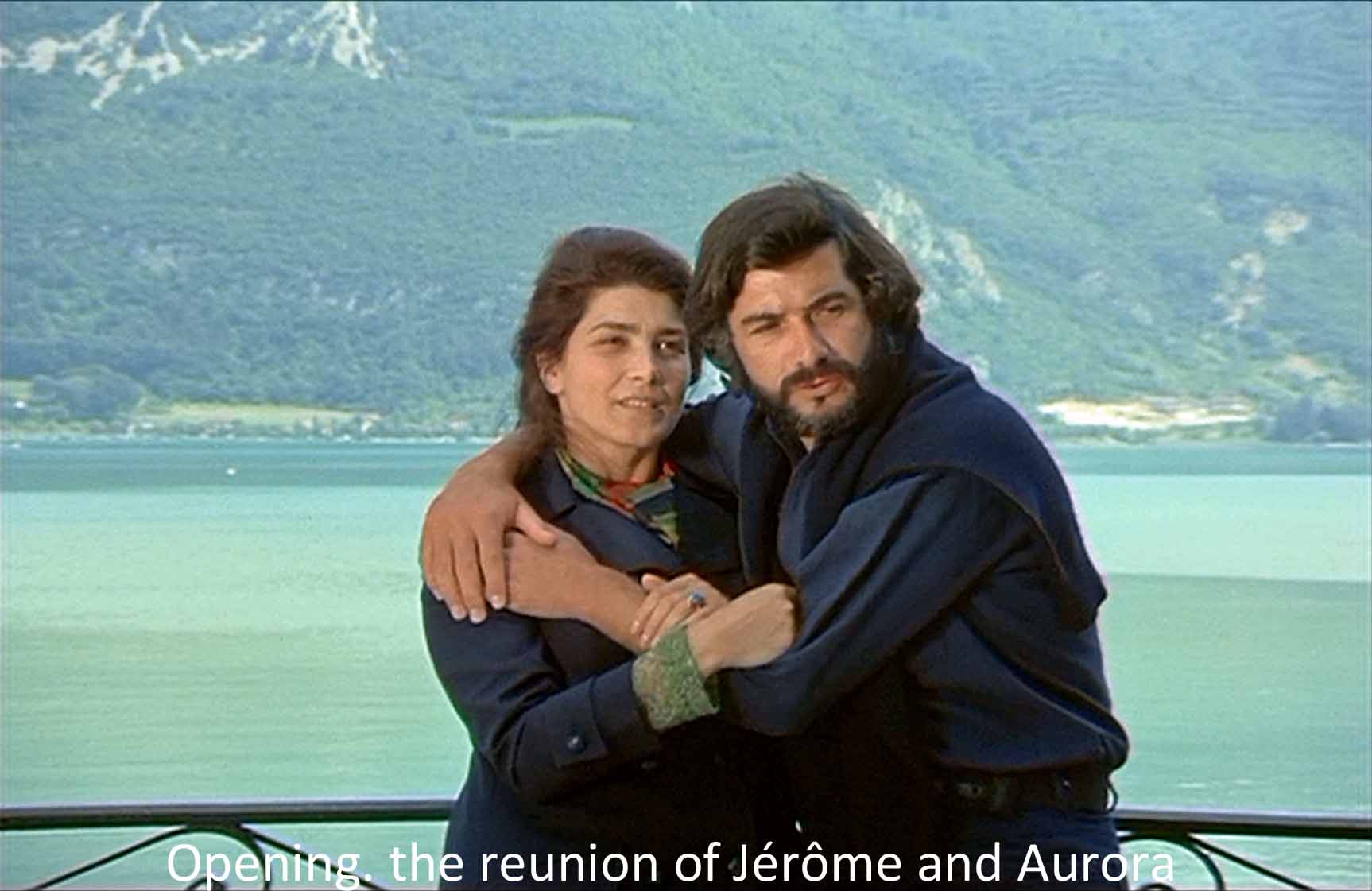

As ever, the opening sets up the situation. The first thing we see is a page with a date written on it in a feminine hand. We are going to see, not events as such, but events as written down by—someone. We then see Jérôme cruising in a speedboat on open water in beautiful Lake Annecy, bridging the border between France and Switzerland (the first of many bridges). He is on open water. Next shot: he is putt-putting down the narrow Canal du Vasse. Above him, a woman standing on a bridge calls, “Jérôme!” He rushes to her, and they embrace enthusiastically, noting how chance has brought them together. She is “Aurora,” and a real person, identifiable by her thick accent. She is the Romanian writer Aurora Cornu, who is playing, in effect, herself. As such she not only stands on a bridge, she is one, a bridge between the fiction of the film and our real world. And the bridge is called “Lovers’ Bridge.”Jérôme is a diplomat—another bridge.

Jérôme and Aurora are obviously friends. Were they also lovers six years ago in Bucharest or more recently in Paris? Perhaps—they can hardly keep their hands off each other.

Jérôme is at Lake Annecy to sell his family house there. Aurora is vacationing, having taken room and board with Mme. Walther who has two daughters, Laura and Claire. (The short story version of this film says they are both sixteen. To me, Laura looks fourteen or fifteen and Claire eighteen plus, but who am I to say?) Aurora takes Jérôme to Mme. Walther’s where he chats with her and Laura.

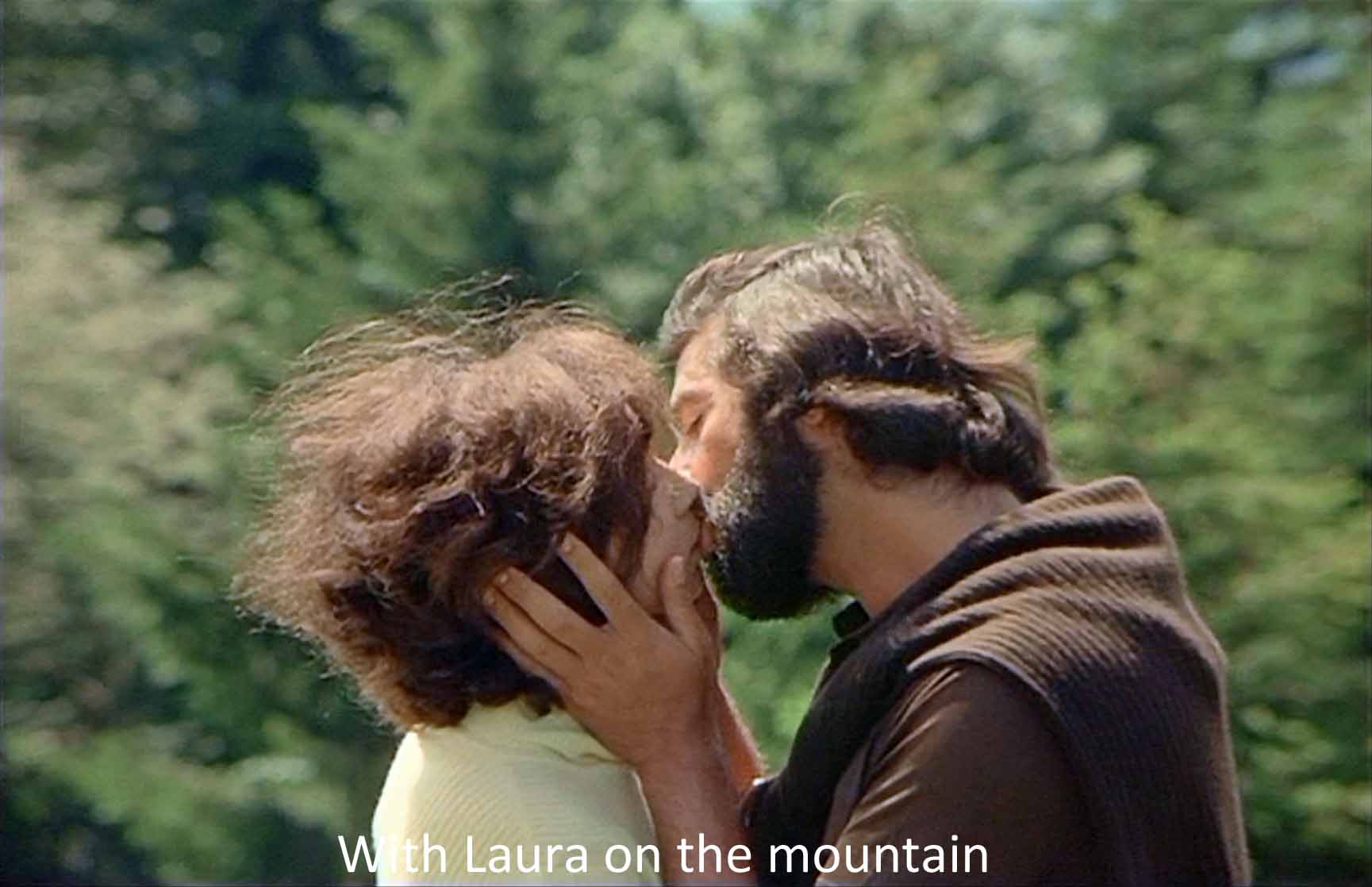

The next day Aurora tells Jérôme that Laura has fallen in love with him. (Béatrice Romand plays Laura, and she became a favorite actress for Rohmer.) There are more chats, and Laura and Jérôme plan a hike up one of the mountains that surround the lake. Perhaps they will stay overnight at an inn at the top, and Mme. Walther is ok with that. On this hike full of potentialities that they talk about, Jérôme kisses Laura. Perhaps as a result of a kiss rather too penetrating for an inexperienced girl, she runs off. Nothing else happens—no overnight at the inn. And when they return to the lakeshore, Laura seems to have lost interest in Jérôme. She pays much more attention to Vincente, a swain her own age, though less mature than she. (Fabrice Luchini plays him, and he too became a Rohmer favorite.)

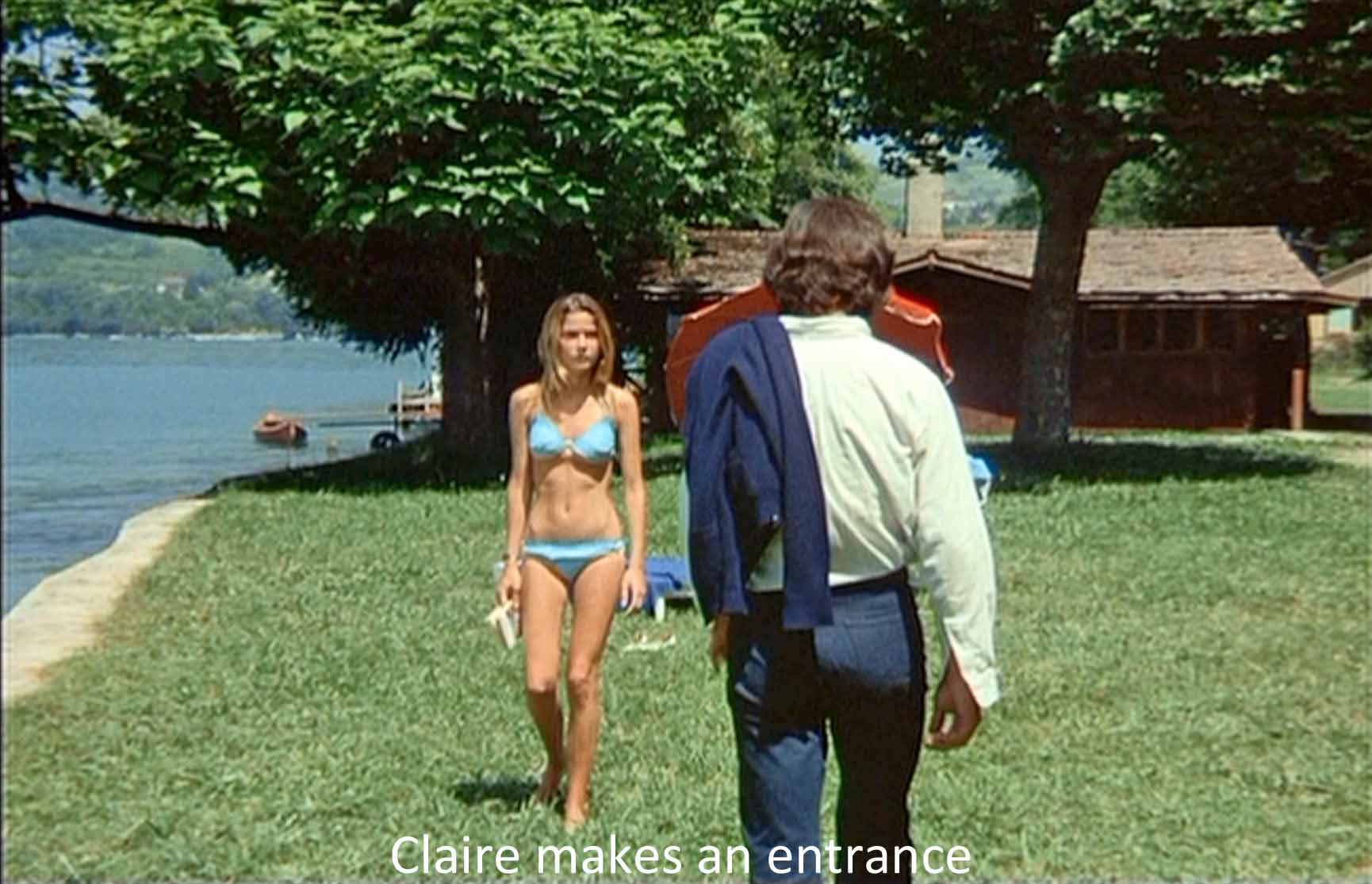

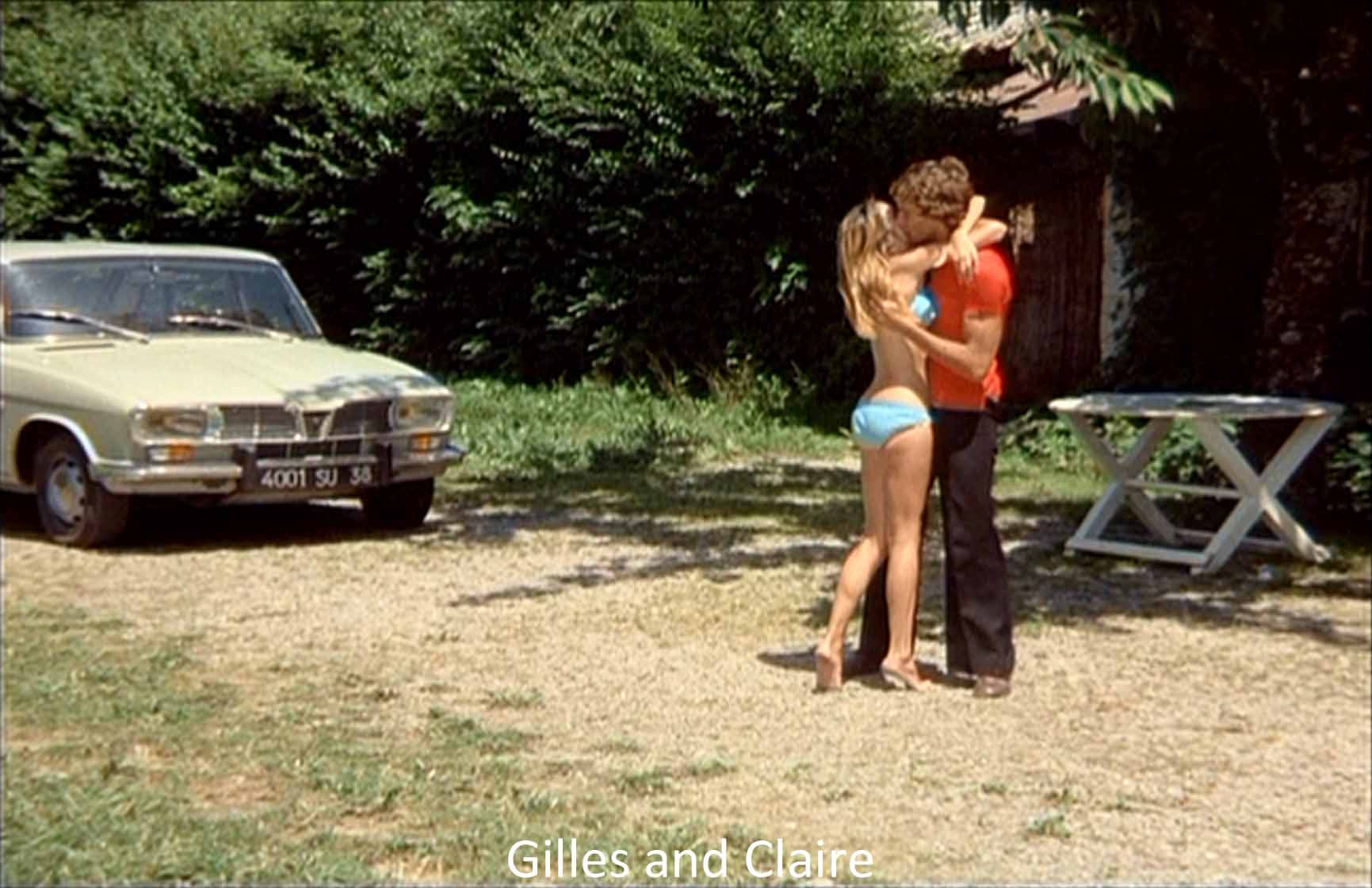

Claire appears and Jérôme transfers his attentions to her. She is a slim, blond, vapid “hottie” (Laurence de Monagham). She shows no interest in Jérôme at all, for she is heatedly in love with Gilles (Gérard Falconetti). He is a rather testy and unpleasant hunk in (probably) his late teens. He can put this hand on Claire’s knee and does—no problem. But our hero, pushing forty, when he becomes fixated on Claire’s knee, is full of fears and hesitancies.

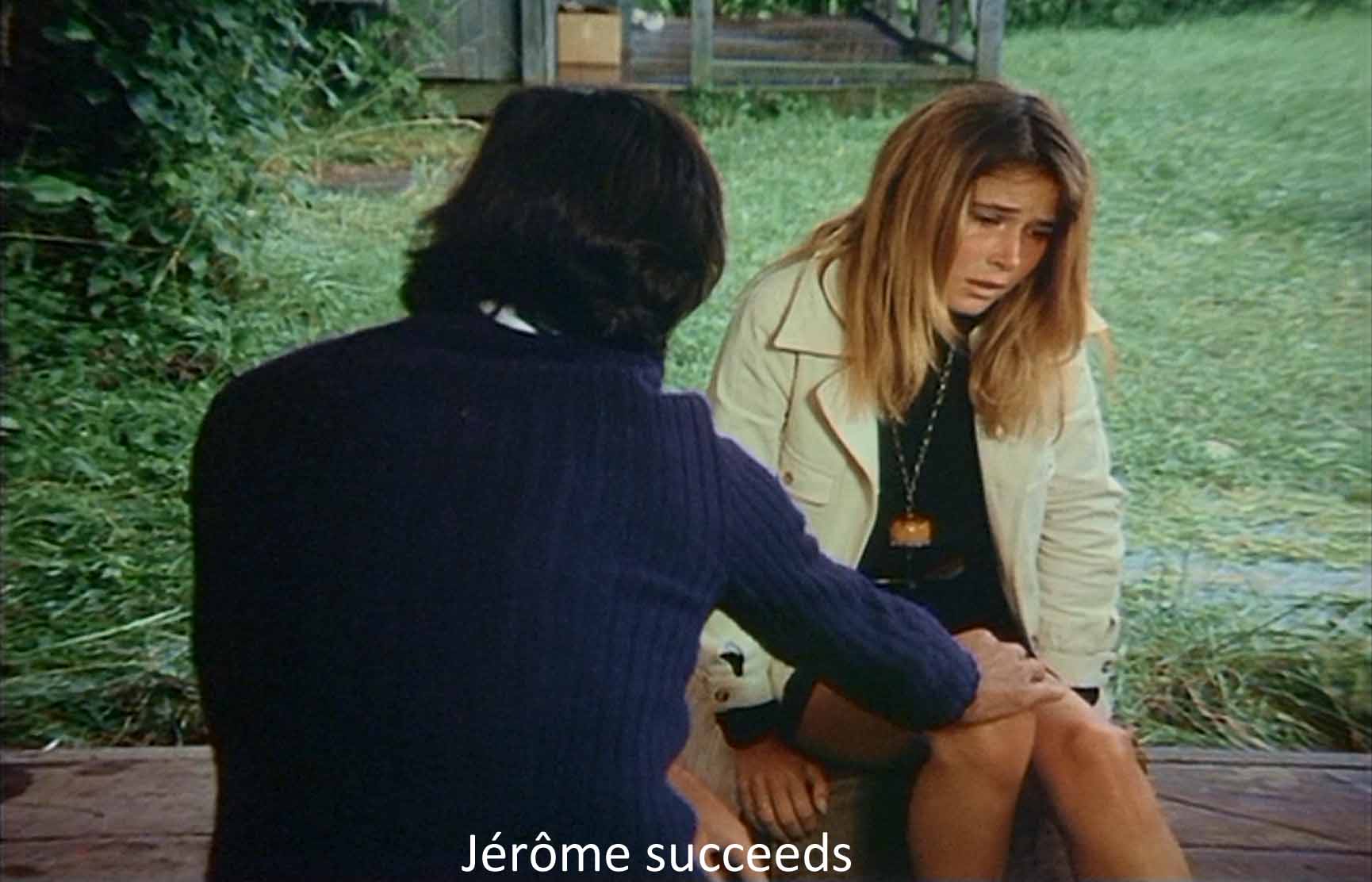

Nevertheless, he does succeed in touching it. Through a series of chance happenings, Jérôme finds himself alone with Claire in a shed—it’s raining outside—and he is able to tell her that he saw Gilles embracing another girl when he was supposed to be visiting his mother. She cries bitterly, and he is able to caress her knee by way of consolation.

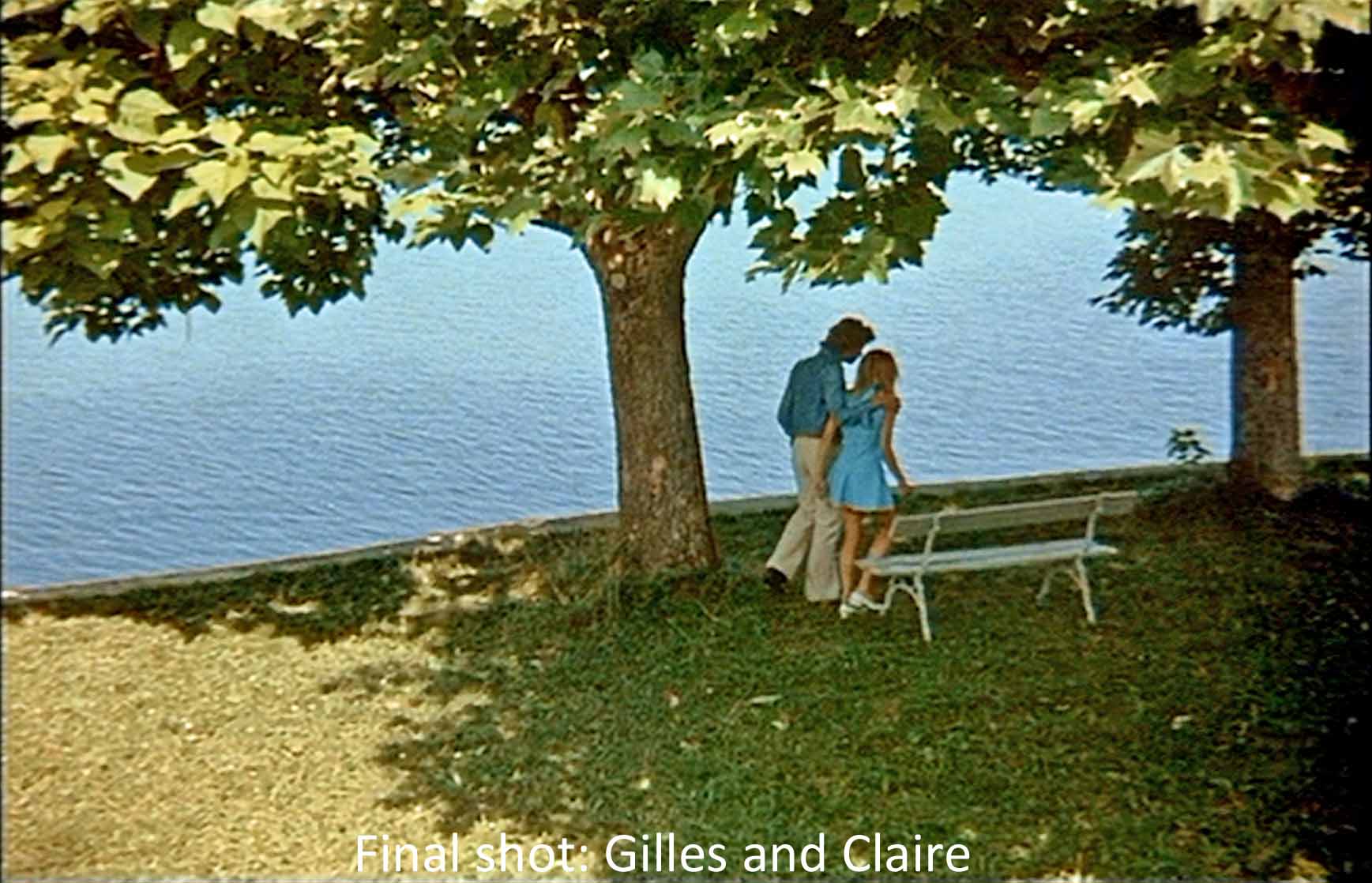

But it turns out—and we see this through the eyes of Aurora after Jérôme has left—that Gilles’ being with the other girl was quite innocent. The final shot shows Claire and Gilles reconciled at the shoreline (a bridge between and water?).

But why does he so intensely, sexually desire to touch Claire’s knee. (Incidentally, we do not meet Claire until 45 minutes into the film, and Jérôme does not home in on her knee until nearly an hour after the start.) The critics answer, predictably, “fetishism.” A man—it’s always a man—displaces his sexual desire onto something other than the appropriate object, a woman’s genitals, because they frighten him. Earlier, Jérôme had told us that he usually knows in advance when a certain woman desires him and pursues accordingly. All his “conquests” are thus scripted. Claire, clearly, is not going to be one, no matter how much he wants to touch her knee, and perhaps that is why he makes a fetish of her knee; he wants an unavailable woman. In an earlier version of the script, Rohmer had Jérôme become fixated on Laura’s ear. That is surely an orifice more sexually appropriate than a knee, as suggested by a famous, not to say notorious, essay by Freud’s English disciple, Ernest Jones (the ear as vagina). But Rohmer retreated to a chaster and more literary source.

Like Pascal in Ma nuit chez Maud, Rousseau provided Rohmer with a scene for this film: the famously erotic cherry-picking episode in Book IV of the Confessions. Rousseau is in Annecy (another connection and bridge). After he lunches with two ladies, they all agree to go into the orchard and pick cherries. Rousseau climbs into a tree and throws cherries down.

One time, Mademoiselle Galley, holding out her apron, and drawing back her head, stood so fair, and I took such good aim, that I dropped a bunch into her bosom. On her laughing, I said to myself, “Why are not my lips cherries? how gladly would I throw them there likewise!”

As you can imagine, this episode created no end of interest, when we read it in French class in my all-boys school. Rousseau, though, followed up no more than we. During the rest of the day, “My modesty, some will say my folly, was such that the greatest familiarity that escaped me was once kissing the hand of Mademoiselle Galley.” But he assures his readers that this act gave him more real pleasure than others that only begin with a kiss and go on from there.

And so with Jérôme. The rounded knee may stand for the rounded breast. Anyway, just caressing the knee satisfies him, but he is proud of what he has done. “First, I exorcised my desire . . . . It’s as though I had possessed her.” “Second, I performed a good deed, in that I opened the poor girl’s eyes to the truth about her boyfriend.” And off he goes to his marriage in Sweden.

Jérôme’s cherry-picking was both less and more sexy than Rousseau’s. In the film, Gilles is the one up in the tree, Claire is halfway up the ladder looking at him, and Jérôme is standing on the ground looking at Claire’s knee (but perhaps higher up—look at the image). Laura sees what he is doing and walks off with a bit of a sneer.

In describing his “good deed,” Jérôme omits to mention his pre-existing hostility to Gilles. Earlier, Gilles had recklessly driven Jérôme’s speedboat too close to some swimmers at a neighboring camp. When the camp counselor bawled him out, Gilles almost provoked a fistfight. That averted, Jérôme came on like a bossy father threatening him and taking the speedboat away. Gilles responded with his own hostility. Jérôme was fulfilling the role destined for him by French psychoanalysis, le nom (or non) du père, Lacan’s lapidary but all-embracing theory about “the law of the father.”

Throughout, Jérôme’s age has been a problem. Like Mme. Walther, another representative of the parental generation, Jérôme consistently misinterprets the young. Compared to Laura but even more, Claire and Gilles, he is overdressed. They show off their bodies; he wears long pants and long sleeves. They play sports; he sits on the sidelines. They embrace and kiss; he desires. He gives fatherly advice to Vincente. At a Bastille Day dance, both the young girls reject him, and he retreats to the sidelines to watch grumpily the flirtations of Laura, Claire, and Aurora.

In his belief that caressing Claire’s knee is a good deed, as in all else, Jérôme is totally self-satisfied—and quite mistaken. We learn in the finale that he has misread who is getting married. We have seen him mistake what Laura wanted. Jérôme is also mistaken about Claire’s boyfriend. We see Gilles and Claire reconcile in the closing scene through the eyes of scriptwriter Aurora after Jérôme has left: Gilles explains to Claire that his being with the other girl was quite innocent.

Notice that Jérôme is mistaken purely because of chance happenings. He just happened to see Gilles in town, whose car just happened to fail and who just happened to see the other girl who just happened to be in the middle of some amatory crisis that called for a hug. Rohmer returns again and again to the question, How can we be moral beings when so much of what we face and what we choose to do depends on chance?

Just as Aurora as real person and real writer bridged from the film to reality, so the reference to Rousseau bridges from the film to fiction, and that is perhaps the real theme of Claire’s Knee. The day after that first get-acquainted chat in Mme. Walther’s garden, Jérôme takes Aurora to his house, where they look at some tiles a Spanish soldier painted in the eighteenth century. (More chance.) They show the blindfolded Don Quixote and Sancho on a horse, and some nobles are fooling them into thinking they are on a flying horse soaring to the sun. Don Quixote is another-self-deceived man like our hero and like him a man who enjoys talking about his adventures as much as having them. The picture leads to a discussion of fiction in which Aurora concludes that not only are the heroes of fiction blindfolded, we all are. Otherwise, if knew what things really were like, we’d undertake nothing. Later she will say (as writers usually do) that the characters that she writes act according to their own desires, not hers. She just records. Uh-huh.

In other words, this film appears to be the story of Jérôme’s adventures at Lake Annecy in the usual manner of films. But we could be watching Jérôme and the others act out a script Aurora has written (the dates that divide the movie into chapters). Are the characters all predetermined? Predestined? Or are they doing what Aurora (=Rohmer?) scripted? Or is it all chance? The realism of film calls for the answer, Both! All! Rohmer has commented on the Don Quixote episode:

One can see the blindfolded Don Quixote as an allegory for the film’s central subject. Jérôme will be blindfolded throughout. He is misguided to the end . . . . Ultimately everyone in this film is simply wrong, about some basic fact (Leigh, 42).

Being mistaken about what we think and do in a world of chance happenings—I think that’s one thing this film is ultimately about. But Rohmer has also said, comparing Jérôme to Don Quixote: “What he really enjoys is not so much his own adventures—anyway there aren’t any of those—but the possibility of telling the novelist what happens afterwards” (Leigh, 42).

Jérôme and Aurora discuss his upcoming marriage to Lucinde and his giving up womanizing (although both parties to the engagement have been having affairs). Aurora assures him that Laura has fallen in love with him, and together they arrive at the idea of a story in which a middle-aged man becomes involved with a schoolgirl. And this is the story—the script— of the film to which Jérôme repeatedly refers.

Notice how the opening sequence imitates the way a fiction takes shape in the mind of a writer. First, Jérôme has no particular direction—free association. Then he is narrowed into to a specific channel: focus. Then chance or luck brings two people, a writer and a character, together and starts a plot.

The film comes in sections, marked by title cards with handwritten dates on them. They mark off the scenes of the movie like days in a diary. Whose hand is it? It’s a woman’s, and probably we are to think Aurora, for only she sees it all.

In short, we have a film which pretends to be about a middle-aged man’s flirtations with two teen-aged girls, but it is really about our lives as fictions. Do we determine the things that happen to us? Do we determine our own actions? Or are they scripted? Or are they the result of chance? Then, what does choosing (free will, if you will) mean? When I think about a Rohmer film, I find myself annoyed at the slowness and the endless talk. Then, suddenly, I feel as though I’ve stepped into an abyss. And as Nietzsche has said, if you stare into an abyss long enough, the abyss stares back into you. That mot feels as though it applies to Le genou de Claire, but I’m not sure how.

What I am sure of is that I am trying to write about a film that seems entertaining, charming, even trivial, then, suddenly, it opens into deep human fears about who and what we are. Do we have free will or does chance govern our actions or does some higher power? It’s a remarkable film, quite unlike 99% of the films one sees, a small masterpiece from a most un-flamboyant director.