Countless film buffs have said that this is the greatest film ever made. It has evoked many books and a legion of articles. I doubt if I can add anything new, and inevitably, I will repeat points others have made (and in a footnoteless format). My aim is not to add to this scholarly mound, but to give you a route into enjoying this masterpiece.

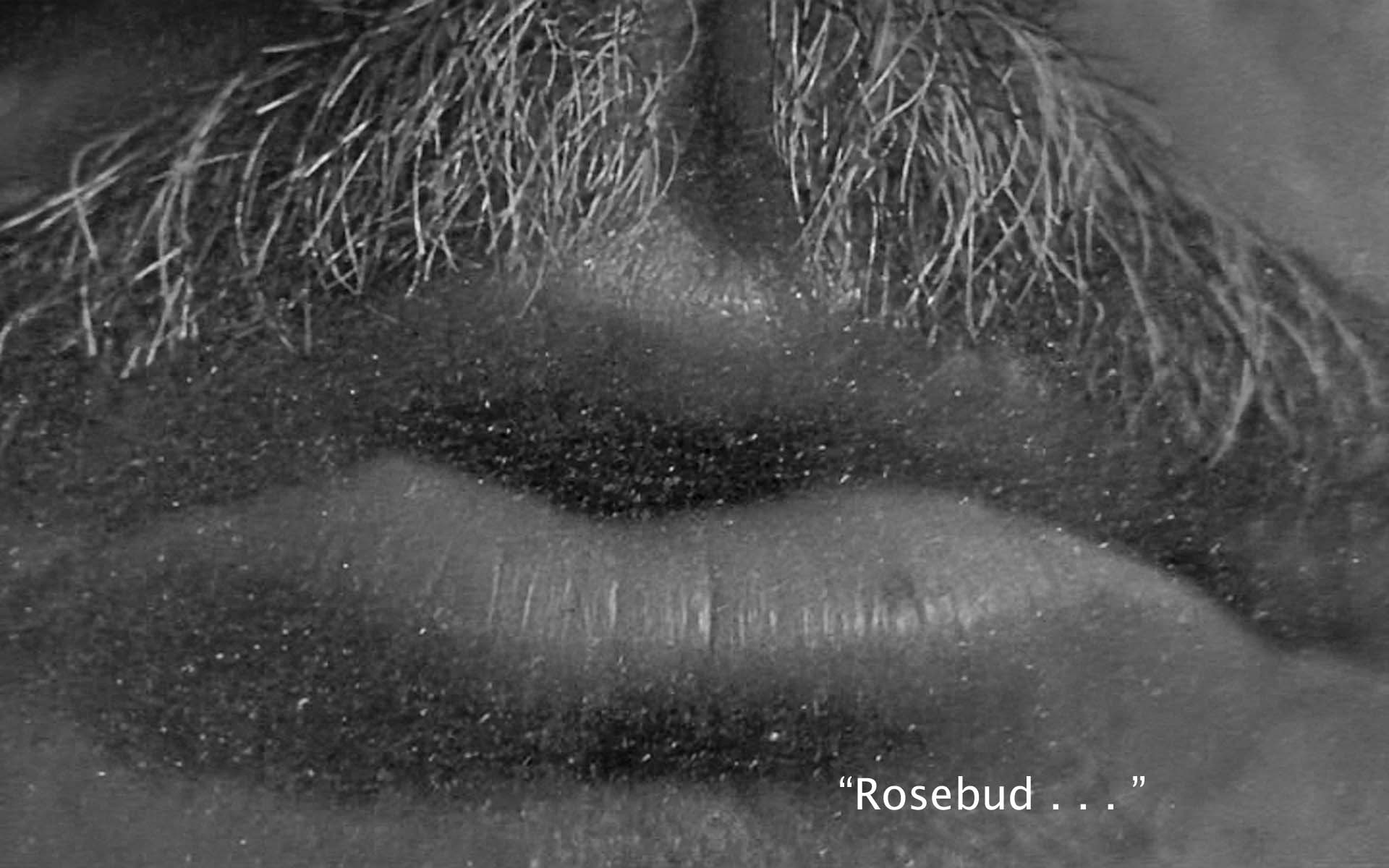

You can begin with the artful structure of Citizen Kane. The film opens and closes with a “No Trespassing” sign. Nevertheless, in the opening, the camera penetrates fences and gates into quite artificial shots of Xanadu, the vast estate of Charles Foster Kane, a castle topping an exotic landscape. We see, first, monkeys, then gondolas, followed by architecture from every period to find a high gothic window and the huge lips of Kane (played by Welles himself) whispering “Rosebud!” as he dies. At the end of the movie, the camera reverses this path, backing away from the chimney smoke (of the sled, presumably) until the last thing we see is the “No Trespassing” sign again.

The two No Trespassings contain the rest of the film, which consists of two parts. First, after that shot of Kane dying, the film cuts to a “News on the March” newsreel (like the old March of Time shorts). It tells the public story of Kane’s life and career. But what did “Rosebud” mean? The editor assigns a reporter, Jerry Thompson (William Alland) to find out. “Rosebud, dead or alive!”

News On The March shows us the outside of the Kane story: the gold mine that made him rich, the newspaper empire, the fantastically wealthy public man running for office, the elegant first marriage and the scandalous second, hobnobbing with Hitler, and pronouncing on the nations issues. We see him as the buyer (and hoarder) of numberless masterpieces. In old age, he is Xanadu’s reclusive landlord, as fabulous as Coleridge’s Kubla Khan.

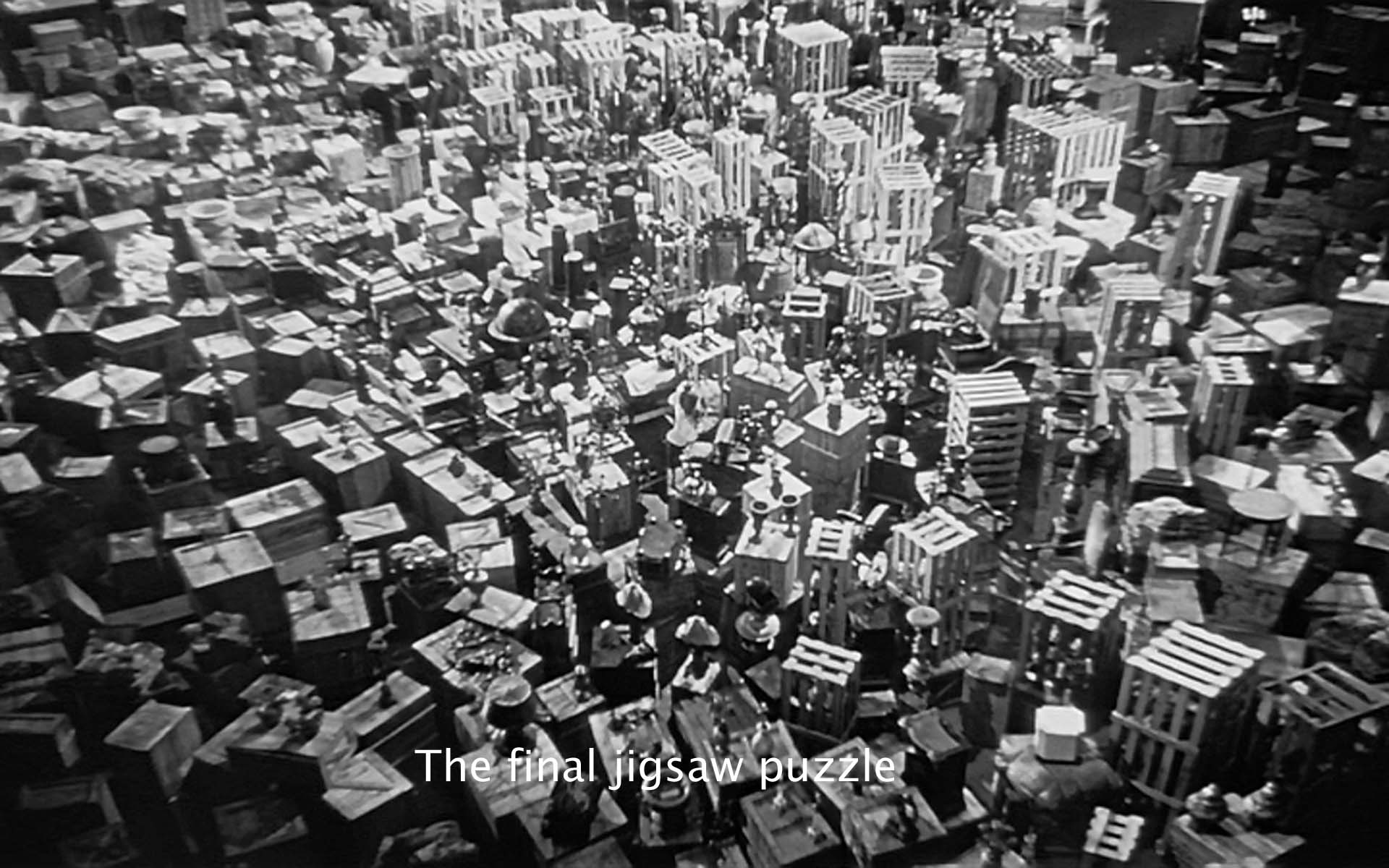

With the newsreel, we have seen the public Kane, Kane from outside. The rest of the movie seeks the private Kane, Kane from inside, as the reporter interviews five narrators (with the reporter himself always photographed from behind, until the end of the film). These five fragmentary interviews finally fail to come together to let us really know that private, inside Kane. We are left with the unassembled pieces of a jigsaw puzzle (a metaphorical image that comes up several times in the film).

The five (or six) interviews give us fragments of the private Kane. The first interview, in a sense, doesn't count. The reporter tracks down Susan Alexander, the second wife, a “singer,” now in a rundown Atlantic City nightclub, played by Dorothy Comingore. Drunkenly, she refuses to talk. But the interview establishes a number of the motifs of the film. First there is the penetrating camera, artfully finding Susan after passing through the nightclub sign and down through a broken skylight. The genius cinematographer Greg Toland’s camera makes many, many such penetrating moves, and his celebrated deep focus shots do the same. The camera acts out our desire to know, to get inside, to learn the secret.

Susan's drinking establishes another theme—I think, the major theme of the film—desire and particularly oral desire. Her apparent sorrow at his death cues us to think about Kane in terms of love, who loved him and whom he loved. Finally, we learn (from the server) that Rosebud is something that even those closest to Kane do not know—or are silent about, a secret.

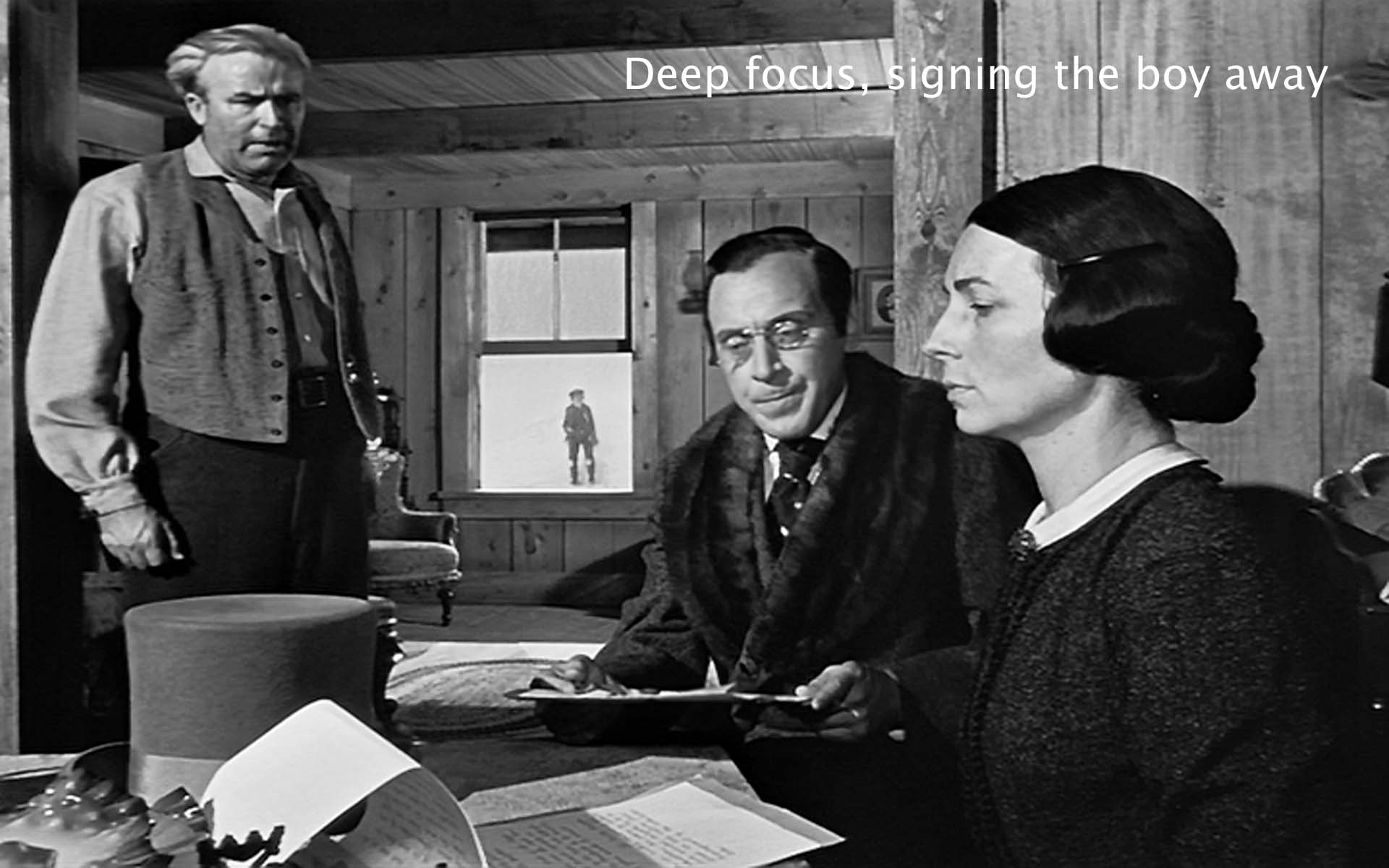

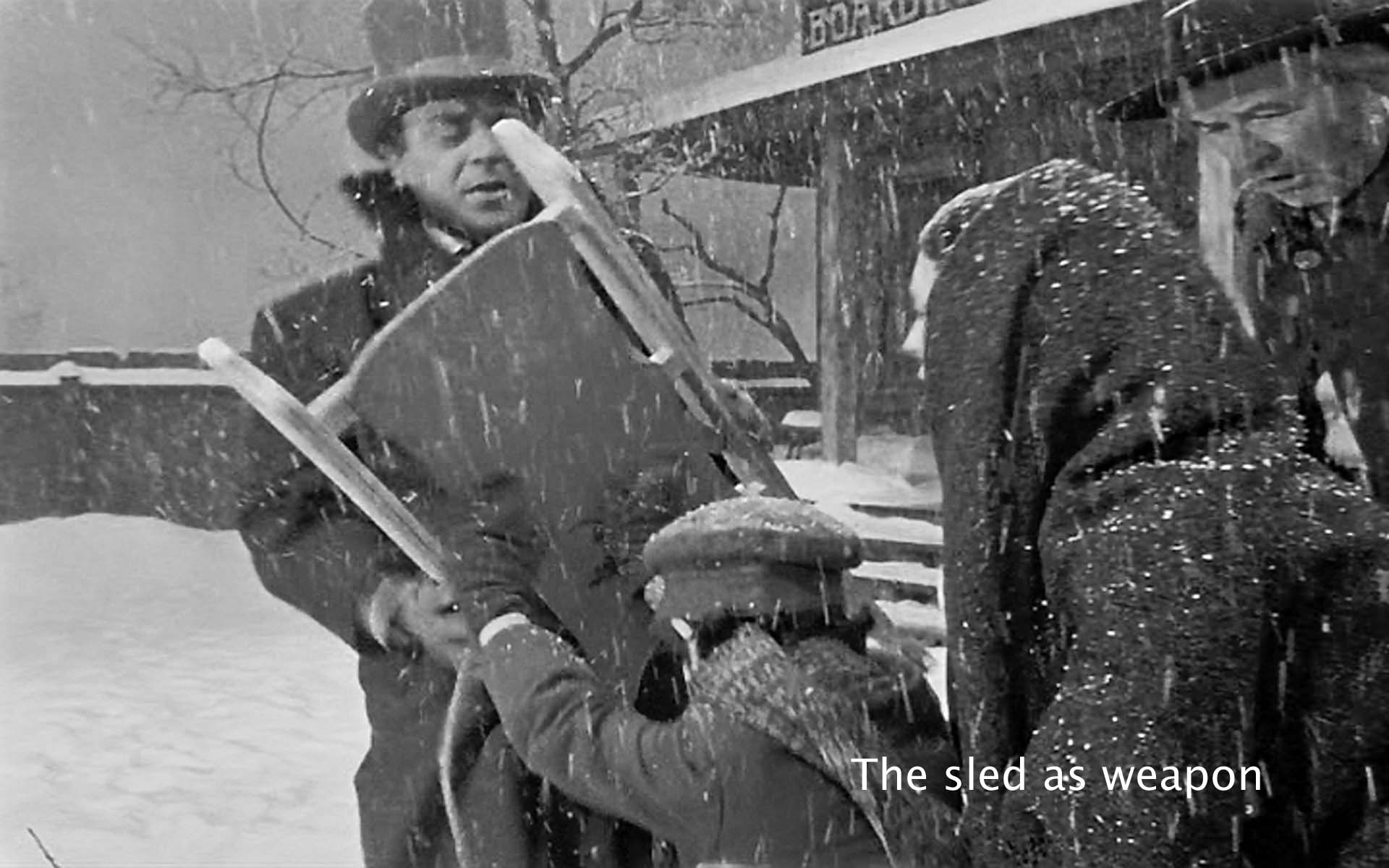

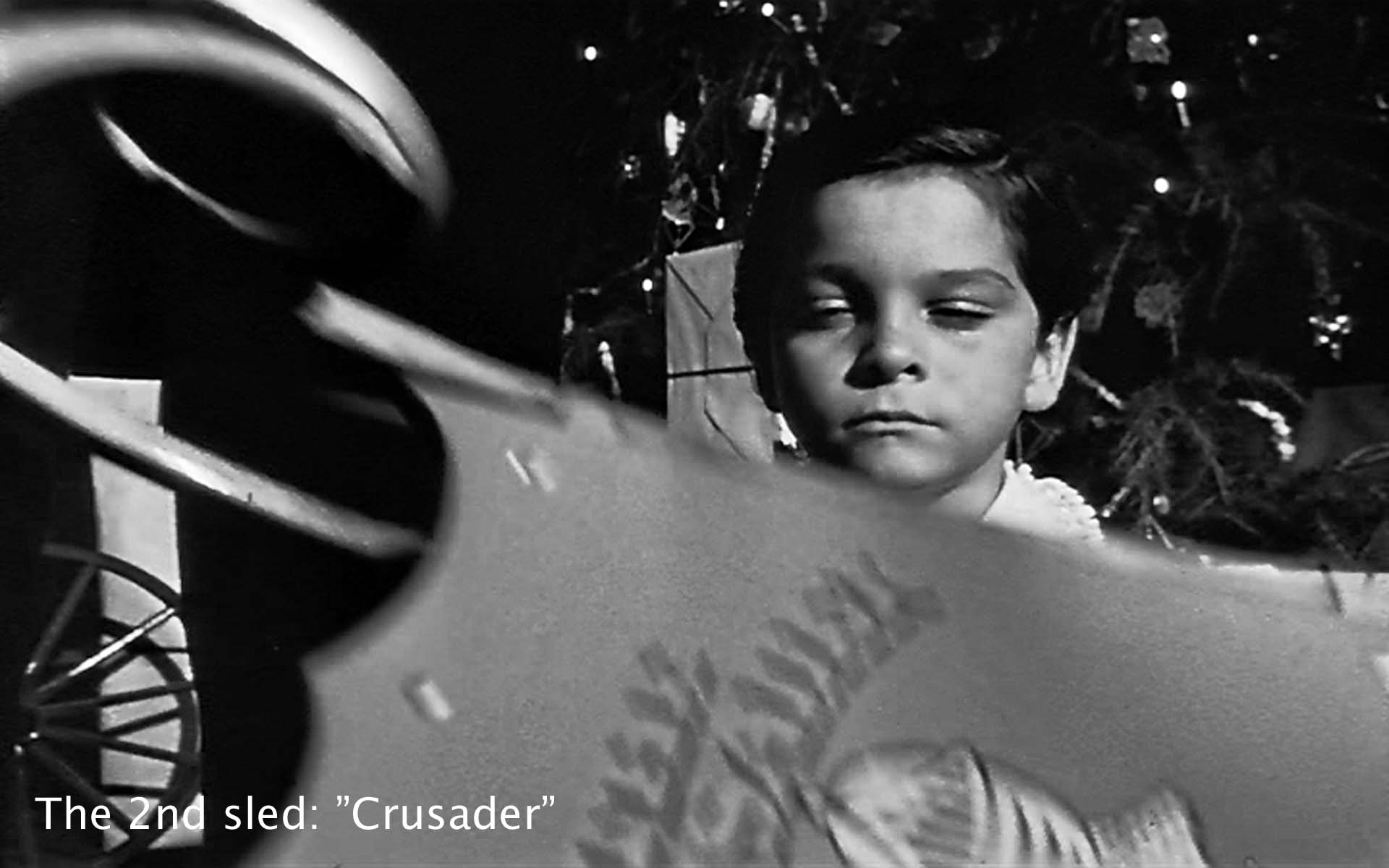

The second interview takes us to the echoing, tomb-like Thatcher Memorial Library, There reporter Thompson is allowed to read the millionaire banker’s memoirs. Thatcher in flashback (George Couloris) tells how, in 1871, Kane’s thin, cold mother (Agnes Moorehead) came into a gold mine and the mother sent him East with Thatcher to be raised as a rich boy; how the boy disliked Thatcher on first sight and struck Thatcher with his sled; and how the adult Kane took over The Inquirer, a small newspaper, and turned it to muckraking yellow journalism, attacking the wealthy (like Thatcher, like himself). Finally, in a flashforward to the 1929 Great Depression, Kane loses this and all his papers.

Thompsons second (or third) interview takes him to Bernstein, Kane’s business manager (Everett Sloane). Kane never calls him by his first name, and we never learn it. Bernstein is of a different social order and Jewish, and Kane, for all his supposed love of the common people, never forgets that. Bernstein himself never calls Kane anything but “Mr. Kane.”

Bernstein recalls early days on the paper, days of reform, trust-busting, stealing the opposition’s star reporters, youthful enthusiasm, exuberance, and celebration. His narrative culminates in Kane’s marriage to Emily Norton, niece of the President (Ruth Warrick), whom he has “collected” as he has been collecting statues in Europe. Asked by Thompson about Rosebud, he recalls, in a seemingly irrelevant aside, a glimpse of a girl in white whom he never knew but has never forgotten. Maybe that was something he lost. Mr. Kane was a man who lost almost everything he had. Desire again, this time for what one has lost, Bernstein’s girl in white.

Bernstein sends Thompson to his third (fourth) interview, Kane’s best friend from schooldays. Jed Leland (Joseph Cotten) is in a nursing home (under the recently-completed George Washington bridge). He had been Kane’s college chum, an impoverished aristocrat. He influenced Kane toward liberalism and reform, but watched him decay into yellow journalism. Leland recalls for our eyes the slow chilling of Kane’s marriage to Emily and his reform campaign for governor, built on attacks on the corrupt machine of Boss Gettys (Ray Collins). He remembers the night Kane met Susan Alexander, who then becomes his mistress. At a mammoth political rally, Gettys uses this fact to try to blackmail Kane into abandoning his campaign. Kane refuses—and is roundly defeated by the scandal. His first wife leaves him. This is 1916, and from this point on, his career goes downhill. Disappointed by Kane's failure to live up to the liberal principles he had at first announced, Leland leaves him to become drama critic for the Chicago paper. As he departs, Kane offers a revealing toast: “A toast, Jedediah, to love on my terms. Those are the only terms anybody ever knows—his own”.

Kane pushes Susan’s operatic career to a dreadful opening in Chicago, and after Leland’s devastating review (completed by Kane), Kane fires him. Leland tells Thompson, about Kane’s efforts to push Susan into stardom, “He was always trying to prove something. That whole thing about Susan being an opera singer. That was trying to prove something.” Psychologically Leland is pointing to an over-compensation for something Kane doesn't or cannot himself deep down believe.

Thompson returns to the El Rancho nightclub where drunken Susan now carries the narrative through Kane’s relentless forcing of her puny voice into the semblance of a career, her miserable, discordant appearances onstage, and her suicide attempt. She tells Thompson, “Everything was his idea, except my leaving him.” More over-compensation. She says to Kane, “You don’t know what it is when a whole audience just doesn’t want you.” And Kane replies, “That’s when you have to fight them.” But, with her potential suicide a source of scandal, his newspapers going or gone, he gives up promoting Susan. They retreat to the vast Floridian gloom of Xanadu, he stalking aimlessly here and there, she doing huge jigsaw puzzles and vainly asking to go to New York and have fun.

Finally she packs her bags to leave him. He begs her not to, but she points out how he is reacting: “It’s you that this is being done to! It’s not me at all. Not what it means to me.” And she leaves him. Yet she tells Thompson that she feels sorry for him, another clue that Kane has somehow missed the mark. He never got what he really wanted—desire again.

Susan sends Thompson to the sinister butler Raymond (Paul Stewart). He picks up the account of Susan’s leaving with—at this point—a famous shot of a screaming cockatoo. It reminds us of Susan in her feathers with her screechy voice. It signals (among many things) the unreality, now, of Xanadu. Raymond remembers the one time before when he said, “Rosebud.” As Susan left, Kane began deliberately smashing her room but stopped, and, muttering the fateful word, picked up a toy glass ball containing “snow” and a winter scene, the glass ball that would fall from his hand and break in the moment of his death.

Raymond accompanies the reporter through the sea of Kane’s jumbled crates. As the reporter decides his quest is pointless, unknown to them, a workman tosses the sled named “Rosebud” into a fiery furnace. Its smoke rises into the sky behind the sign that says “No Trespassing.”

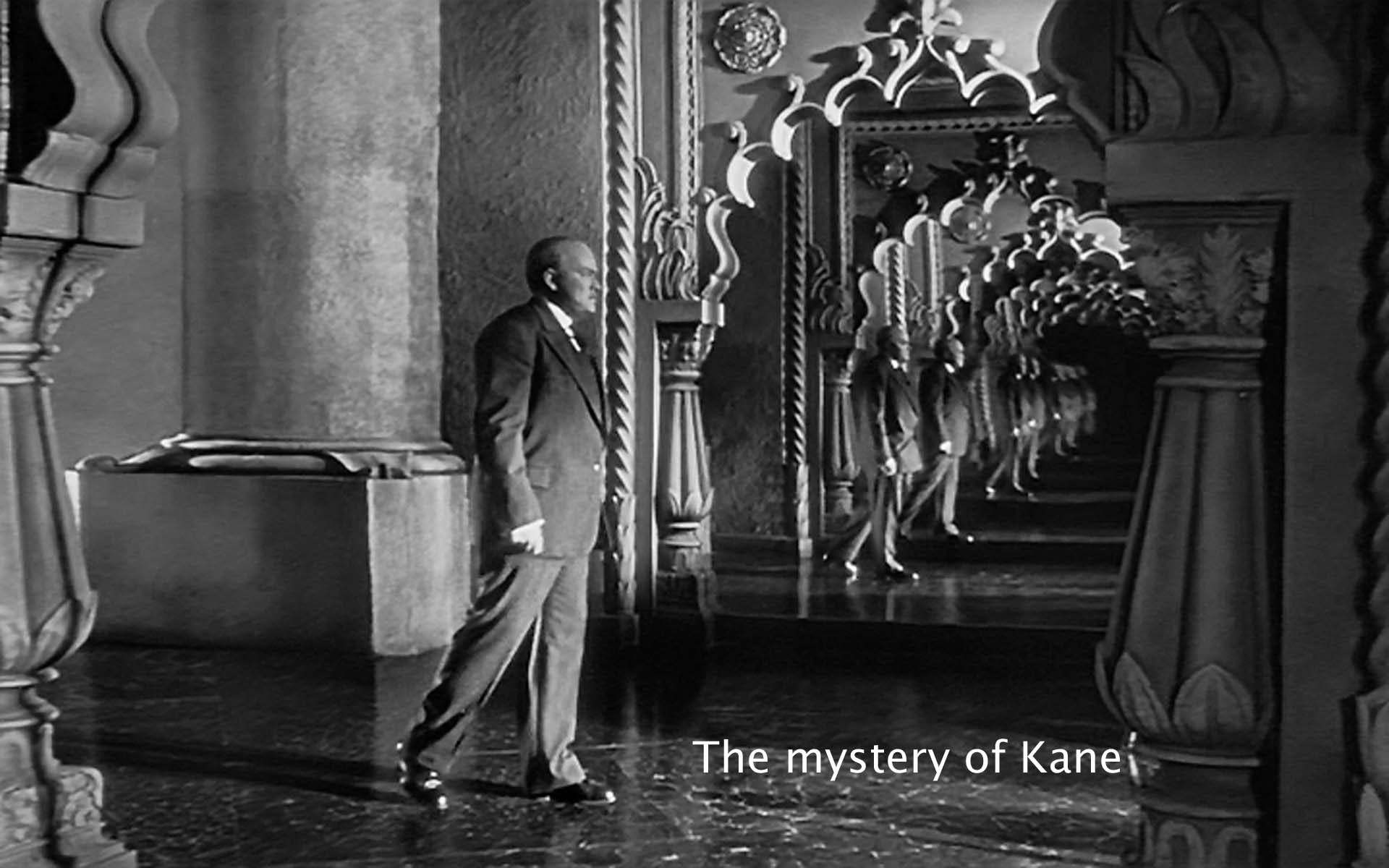

At the end, that huge “No Trespassing” sign is accompanied by quite unreal-looking pictures of Xanadu like those at the opening of the film. This is a film that mixes the unreal—as in those shots—with the intensely real, the kind of material that could—and does—go into a newsreel, shots of Kane with Hitler or Teddy Roosevelt (the latter adapted from a real newsreel of T.R.) But Xanadu looks unreal. In fact, the matte drawing that was rear-projected for these opening shots was drawn by Disney artists. Later, the “Everglades” of Kane’s huge, unhospitable picnic will be background shots taken from one of the King Kong movies, complete with animated pterodactyls (or are they only bats?). It is at Xanadu that we will hear the weird cry of the cockatoo and see in the incredible crane shot of the finale the vast jigsaw puzzle of the “things” Kane has collected. It is here, the newsreel portentously tells us, that Kane is like Kubla Khan or Noah or even, perhaps, Adam in a world devoted to his own wellbeing, “Xanadu’s lord.” He retreated to Xanadu to lord it over the monkeys. Kane is man himself, in an evolutionary sense.

The film builds, it seems to me, on a fundamental contrast between its realistic body and this fantastic unreal Xanadu, emblem of insatiable desire. Welles’ and Gregg Tolands celebrated camera techniques build a similar contrast. The subject they render is realistic—enough like William Randolph Hearst to have earned Hearst’s enmity and opprobria from Hearst’s newspapers—yet Welles’ (and Toland’s) camera render it surrealistically. Lightning sound mixes compress time into the space of a dialogue. “Merry Christmas, Charles,” says Thatcher, “and a Happy New Year” but between Christmas and New Year fifteen years have passed. Ceilings suggest fateful limits pressing down on the characters, and swish pans compress time into space (as in the famous sequence of breakfast-with-Emily). The deep focuses collect long spaces into the flat film frame. Extreme close-ups make the tiny huge. In the scene of Susan s suicide her medicine bottle at the front of the frame is bigger than Kane’s head five feet away. In general, there are vast differences in scale (like Kane’s enormous face on the political poster over the actual Kane on the rostrum).

If I identify the fantastic Xanadu and the exaggerations of the camera with the power of desire over reality—in one case, Kane’s, in the other Welles’s (but surely they are the same!)—I would also think of the structure as an instance of desire. The film is organized, like a Tale of King Arthur or like a mystery story, as a Quest. Who was Kane? What was Rosebud? And the reporter must go to various strange places and seek answers of strange helpers. Both reporter and Kane’s newspaper are “the Inquirer.”