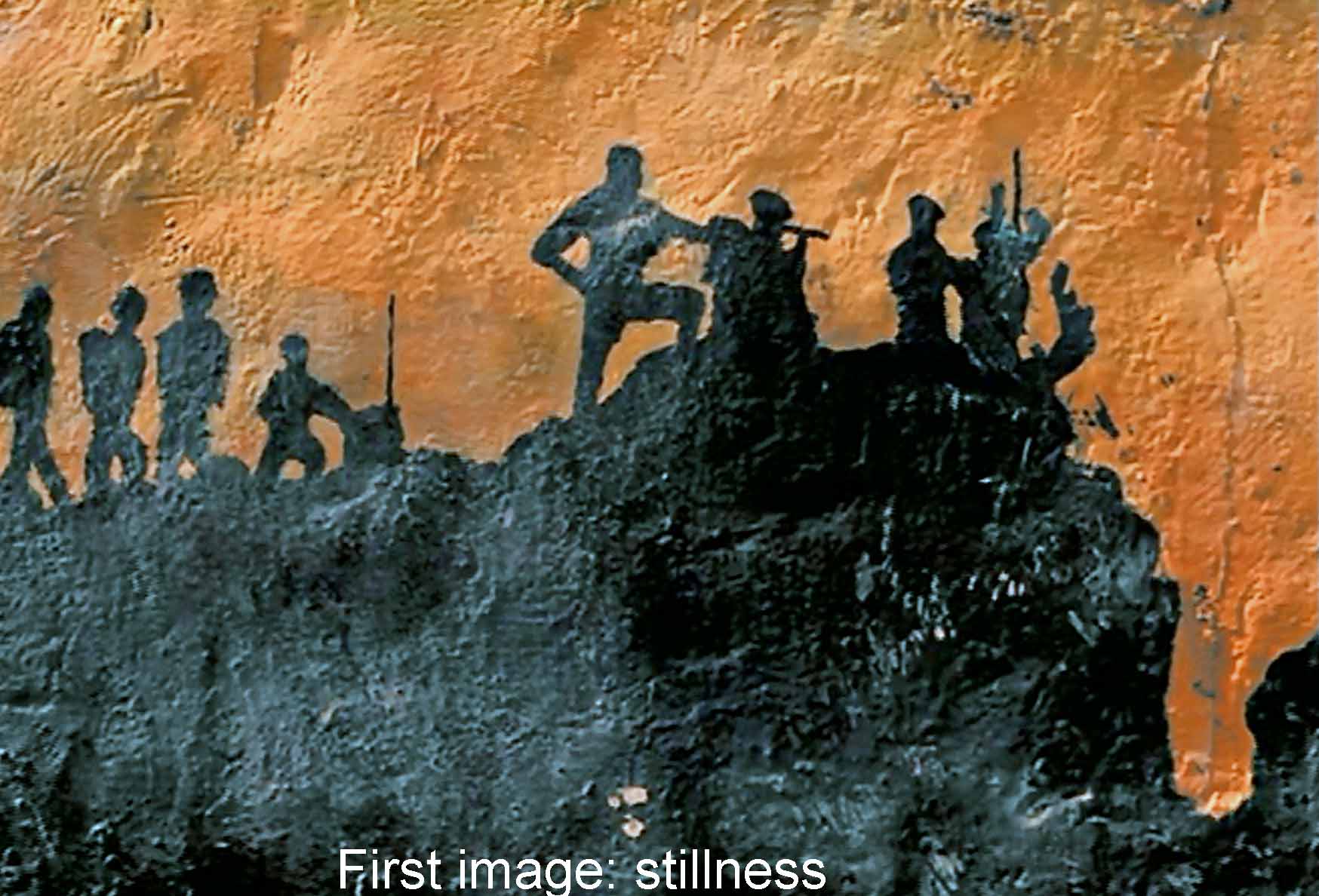

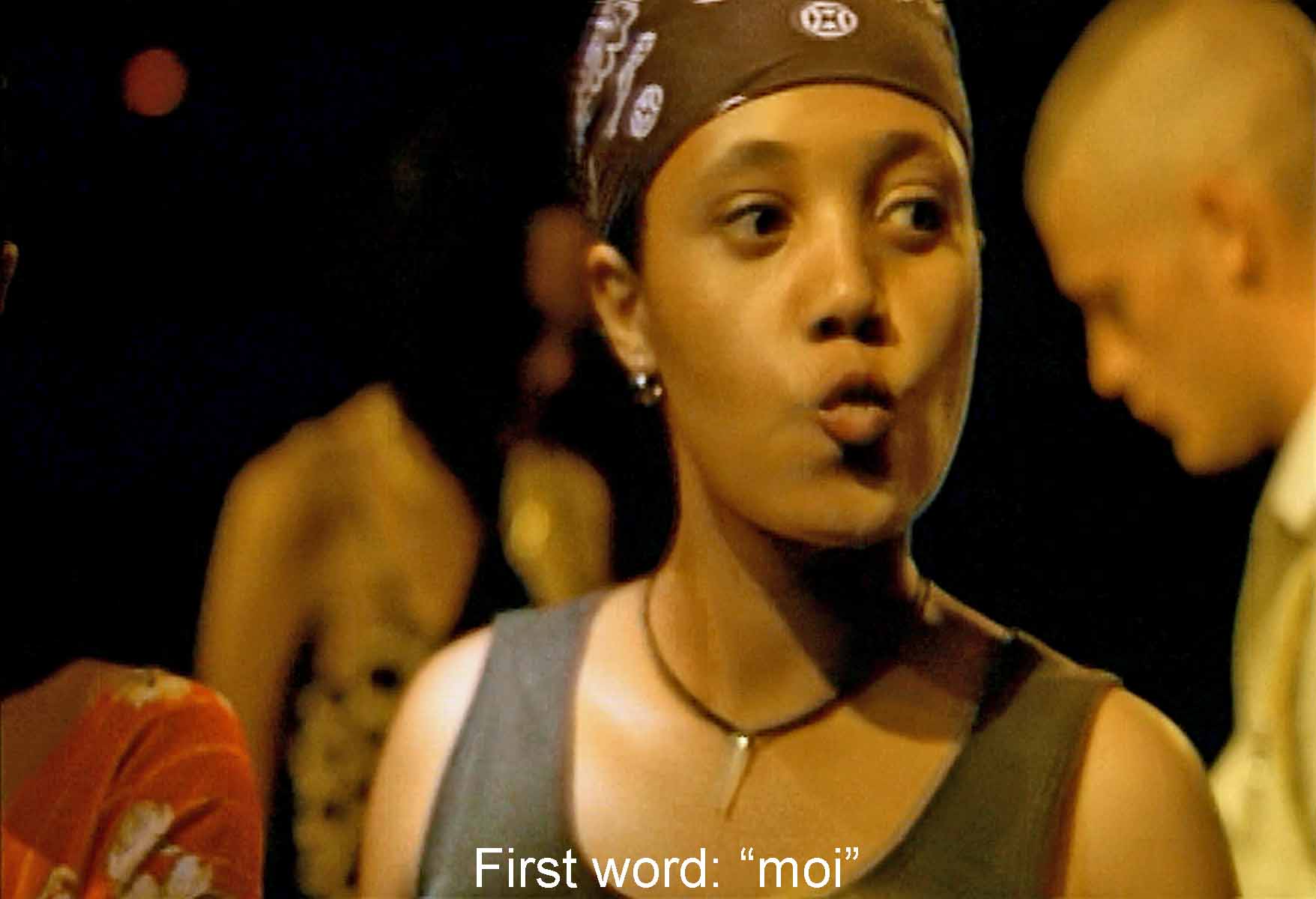

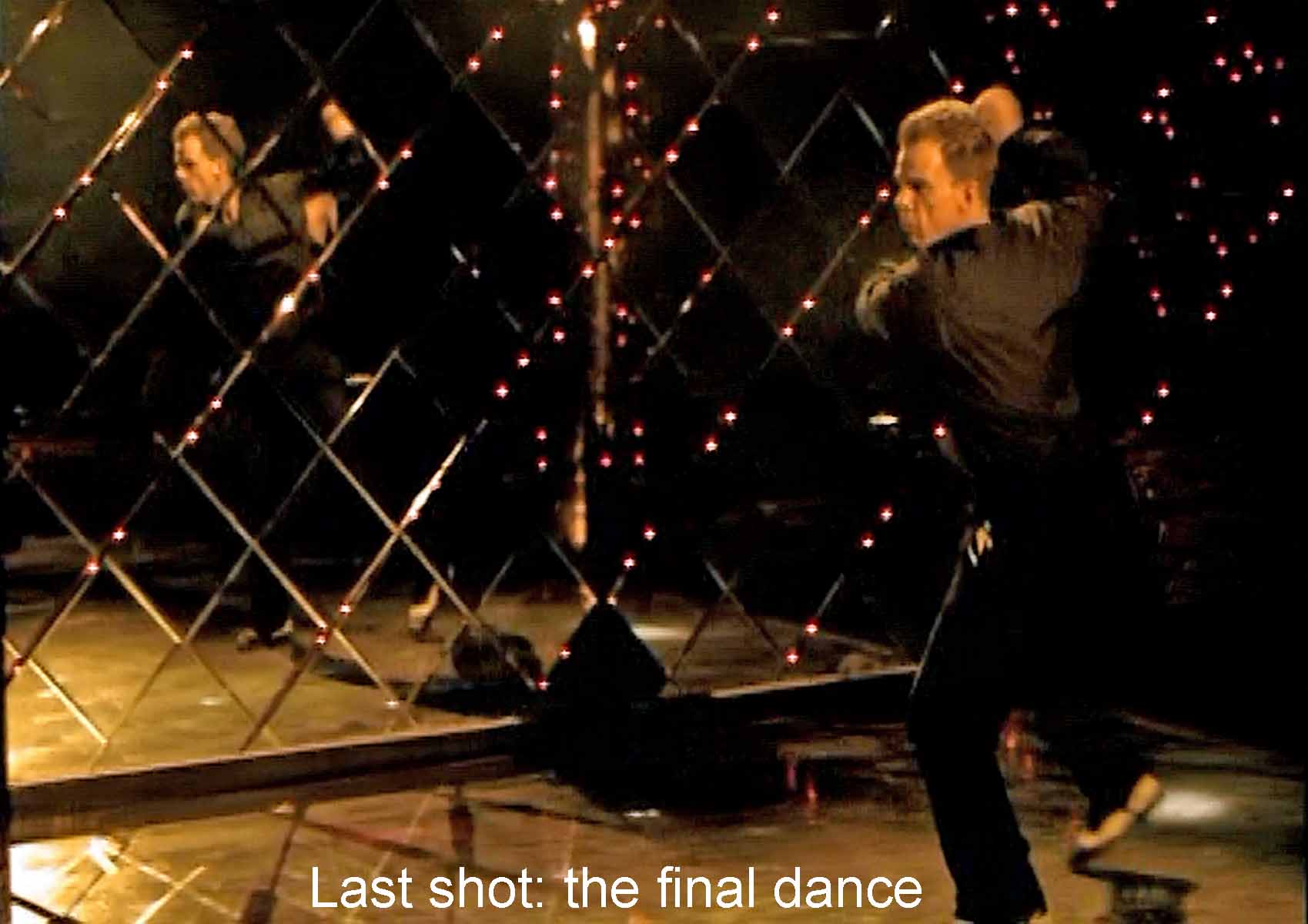

This film begins with utter stillness, a wall painting of Foreign Legionnaires. Then comes a dance by a native girl and the first word. She mouths a kiss at the camera saying “moi,” me. What is this film saying about “me”? The film also ends with a dance, a break dance by a character who may very well be dead.

What's with that last dance? Claire Denis has made a “puzzling movie.” She has scrambled the time scheme with present action and flash forward and flash back all mixed together. This is a film that shows a lot of half-naked men's bodies, and maybe the plot involves a gay love triangle. The film begins and ends with a dance, and it features the French Foreign Legion sustaining colonialism. These are all topics to titillate today's critic.

The mystique of the French Foreign Legion is that anybody physically up to it can join, and you do not have to say who you are. It's a place to escape from the police, a tragic love affair, somebody's vengeance, a wife wanting alimony—whatever. The Legion lends itself to novels and movies about identity. Earlier movies tended to give the Legion a romantic, heroic treatment. Denis gives us a much tougher yet almost balletic Legion. And she uses it to raise questions about identity, character, and psychology that send critics into mysticism and rhapsody. Fair enough. The film merits such a response, and certainly Denis' radically scrambled time scheme invites it. So what's it all about?

The film takes place in a Foreign Legion post in a French colonial possession, Djibouti, a tiny country sandwiched between Eritrea and Ethiopia in the horn of Africa. A train ride near the beginning shows what a desert wasteland this colony is. The action must take place between 1962 when the Algerian War ended and 1977 when Djibouti gained independence.

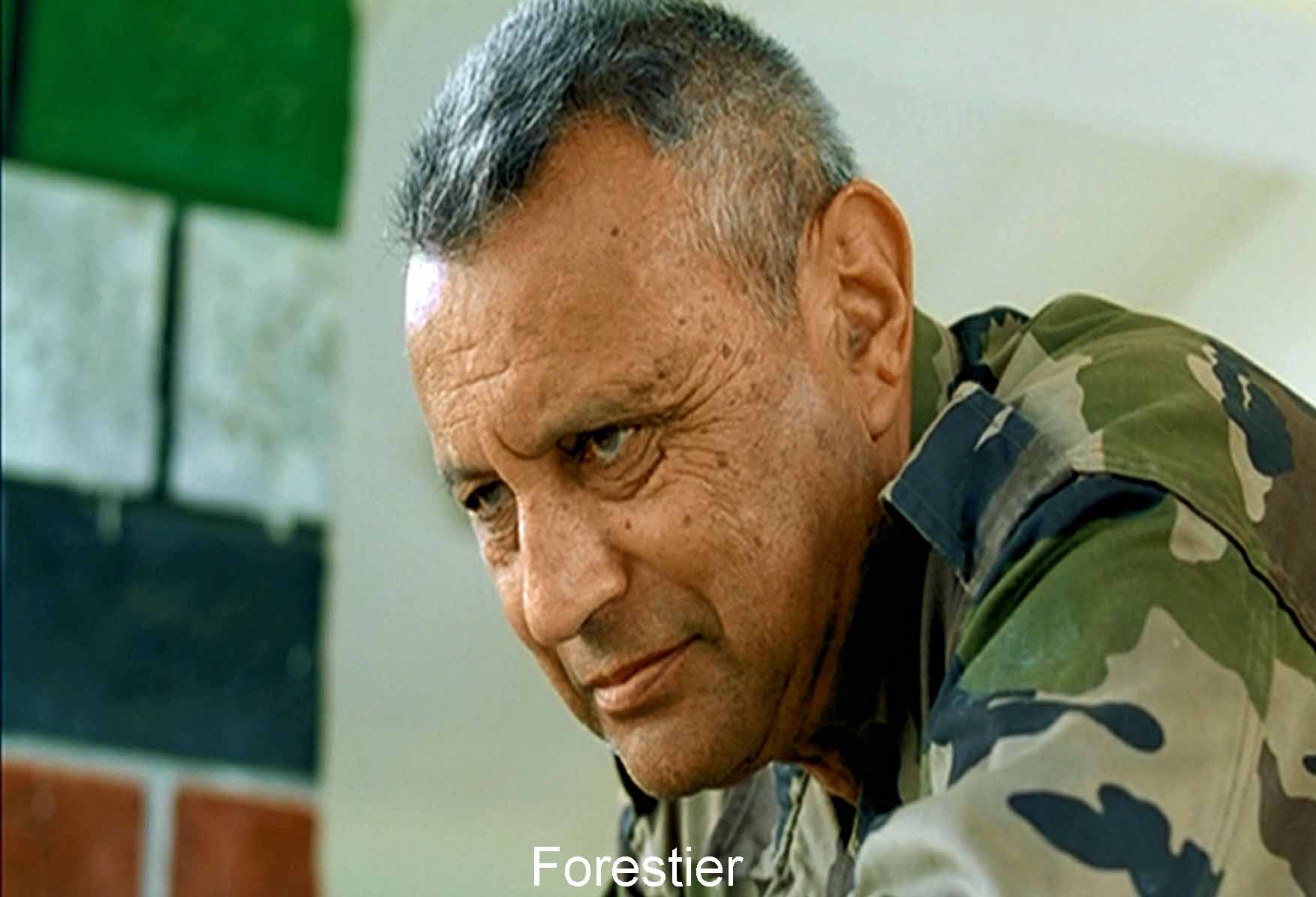

The post has a commandant, Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor), a veteran of the Algerian War which stuck on him “rumors” (of torture?). With this casting Denis gives a nod to Godard’s Le Petit soldat (1960) in which Michel Subor played a character also named Bruno Forestier.

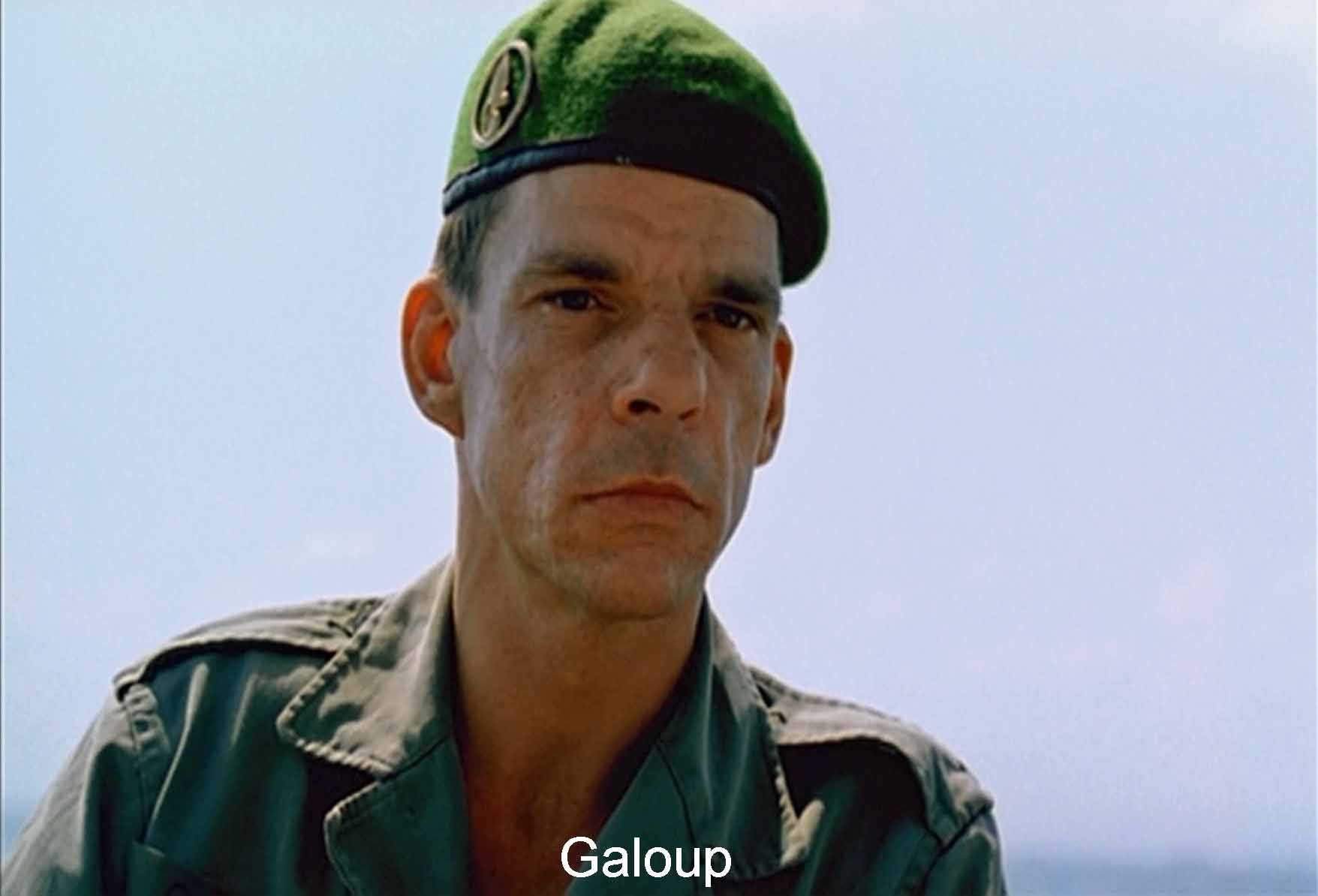

Under him is Master Sergeant Galoup (Denis Lavant), a tough, demanding ‘watchdog” for Forestier’s “flock” of “bastards.” Galoup obeys, admires, and “loves” his commander as the Legion demands. Then there are about twenty enlisted men. A good, if severe leader, what Galoup demands of his men, he does himself—even more strenuously. He, like Forestier, keeps himself separate from them on their play time. He keeps and apparently loves an Arab mistress.

An airplane plus longboat brings a new recruit, Gilles Sentain (Grégoire Colin), who sets the plot in motion. He becomes a favorite among the men. Forestier recalls, “Sentain seduced everyone. People were drawn to his calm, his openness.” But not Galoup. Galoup resents him. “He had no reason to be with us in the Legion.”

A helicopter crashes into the sea, killing one man, and Sentain heroically rescues the other from the sea. In an inspection line-up, Forestier publicly praises his bravery (enraging Galoup). Later when Sentain is standing watch at night, Forestier compliments him on his attractiveness.

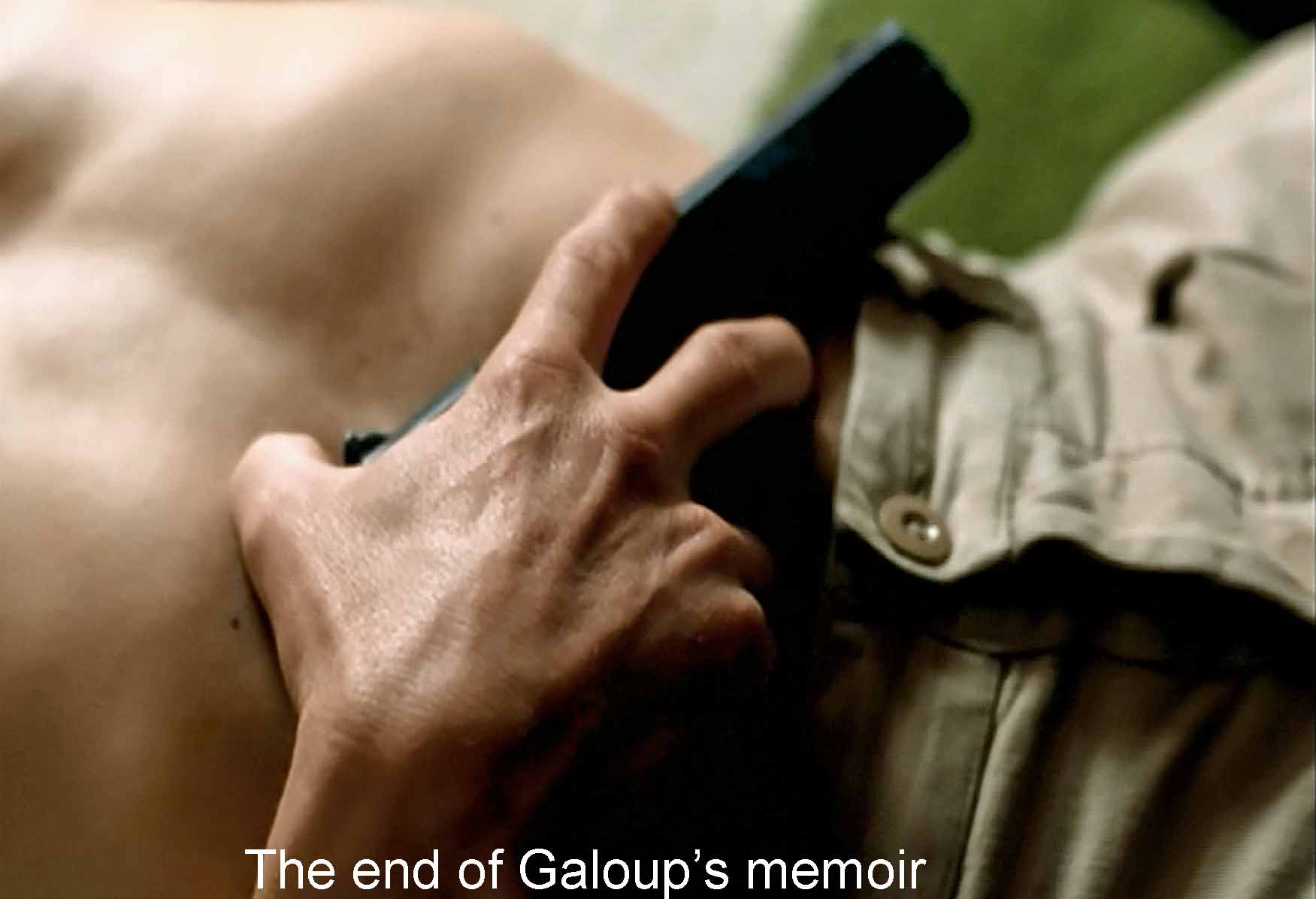

At the funeral for the dead airman, Galoup recalls in his memoir, “That day something overpowering took hold of my heart.” “I thought about the end, the end of me, of the end of Forestier.” He resolves to kill Sentain.

Denis has said that she based her film very loosely on Herman Melville’s profound novella, Billy Budd (unpublished at Melville’s death in 1891). And she used in spots music from Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd (1951).

In 1797 Billy Budd is impressed from an American merchant ship onto Captain Vere’s British warship (vir = man). First mate Claggart envies Billy for his beauty and innocence and popularity with the men. Claggart accuses him of mutiny to Vere. Billy, muted and frustrated by his stutter, strikes Claggert who falls dead. Captain Vere insists that Billy be executed under the wartime laws in effect. Billy’s last words are “God bless Captain Vere.”

As I read it, the novella raises all kinds of questions about right and wrong, law and justice, and one’s responsibility to one’s fellow man. Denis takes a different tack. She keeps the basic plot but she makes some interesting changes. She keeps the triad of commander, non-com, and enlisted man. She keeps the idea of the non-com’s deep resentment of the enlisted man and the non-com's accusing the enlisted man to the commander. But she changes the denouement. It is Claggart/Galoup who passes sentence; it is Claggart/Galoup who kills or tries to kill Billy/Sentain; it is Claggart/Galoup who tells the tale in his memoir. Forestier/Vere’s role has been cut back from judging Billy/Sentain to just dismissing Galoup from the Legion when his crime is discovered.

Some critics have generated elaborate philosophical ideas about identity to explain Galoup’s irrational hatred of Sentain which even he does not understand. Others have suggested a repressed homosexual desire. Certainly these are possibilities, but I think there is a simple answer: sibling rivalry. Forestier is an obvious father-figure, and until Sentain arrived Galoup was the favored eldest son. Galoup played chess and billiards with Forestier, and they conversed on familiar if not equal terms. Forestier had complimented him, “You’re a rock, the epitome of the Legion.” When Forestier admired and praised Sentain, Galoup feared that Sentain would take the father’s love and admiration from him, and he hated Sentain. Even more simple: Forestier is the only relationship Galoup has in the Legion. The possibility of losing it is appalling.

If Forestier be father and Galoup son, then the Legion could be a nurturing mother, not only for Galoup but all the men. It (she?) supplies food, home, love (in limited quantities) and supervises every aspect of their being.

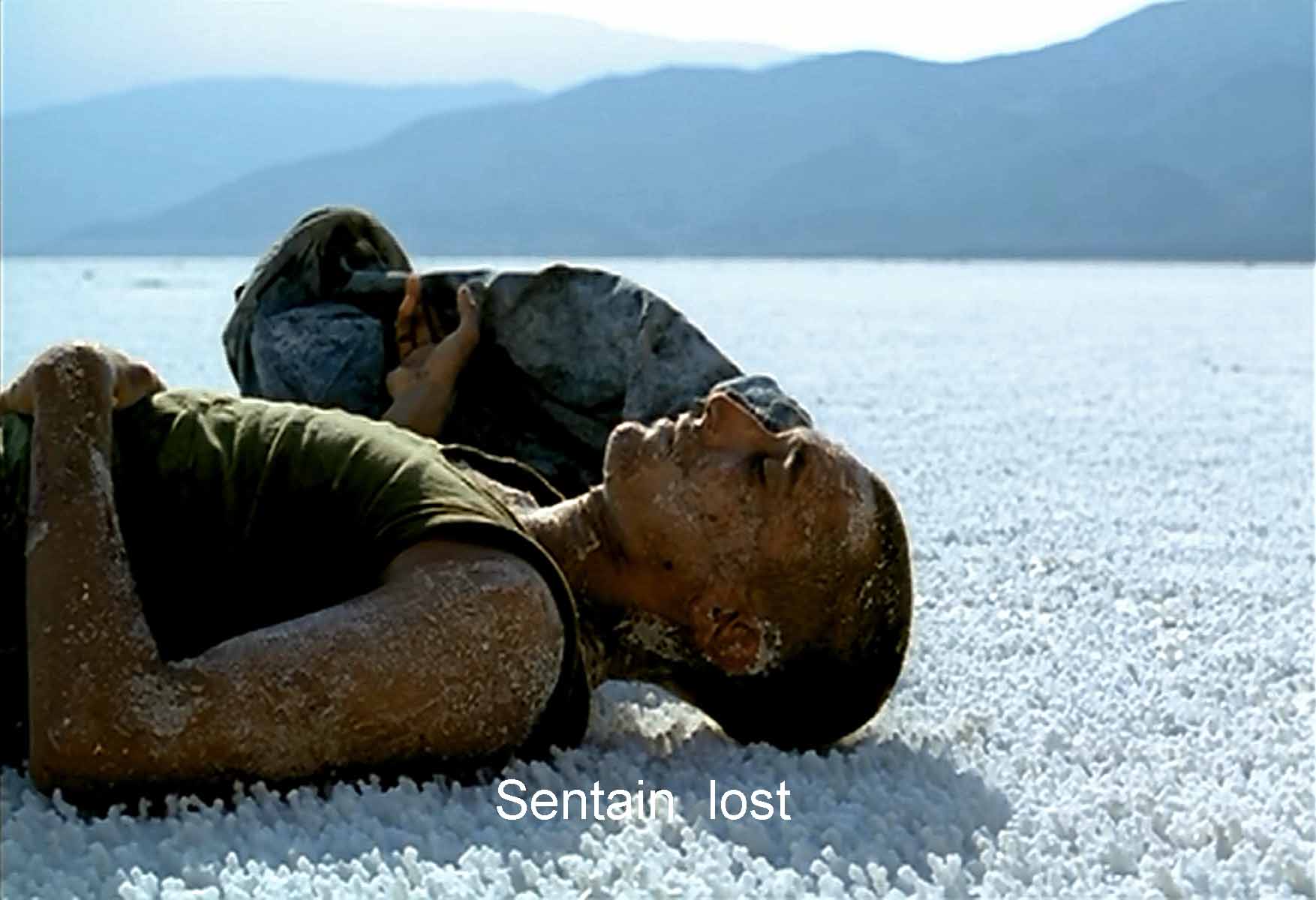

Galoup creates a plan to kill Sentain. Carefully, he gets the men off the base to repair a far-off road that needs no repair. (Most of the squad’s labors seem pointless.) He abuses one of the men, knowing that Sentain will try to intervene. He does and strikes Galoup (like Billy Budd). But Galoup does not die; instead he administers Sentain’s punishment himself. Legionnaires drive Sentain far out in the desert and leave him to make his way back if he can. He cheerily expects to do so. “Say hi to the Commandant,” are his last words, as if to taunt Galoup with his role in the older man’s affections. But secretly Galoup has buggered his compass, and Sentain becomes hopelessly lost.

When the crime is discovered, Forestier dismisses Galoup from the Legion. Galoup’s response: “Admit that you hate me for it,” as though the real loss for him is Forestier’s love, the father’s love. When at the end of the film, Galoup has been kicked out of the Legion he says he is “unfit for life.” He is like a child kicked out of the nuclear family, bereft of everything he had or was. He has become nothing.

That idea of the Legion and commander as family leads to another theme: identity or the self. What is it? In this film, the self, at least for the legionnaires, is the body. They are only what they can perform with their bodies, push-ups, jujutsu, underwater fighting, plunging through obstacle courses—that is what you are. Even some strange mystical movements are treated as group calisthenics. The Legion defines you. Forestier speaks of a certain “elegance” he wants in his legionnaires. Hence they have to have perfect creases in their pants, neatly ironed collars, carefully creased short pants that that show off those bodies. Pointless as these and their other exercises are, they become the legionnaires’ identity, in Forestier’s term, an interior “elegance.”.

The bodily moves we make are our identity—that seems to be Denis’ point. The film begins with stillness, a wall painting of legionnaires—no motion at all. Then we see a group of native women dancing. One speaks the first word of the picture: she mouths a kiss as she says “moi‘—me. The movement of the dance defines her “me.” (Later we will see some native women define themselves by the number of stripes in the pads they sell.) And the film ends with a dance, a particularly energetic and puzzling break dance.

Denis’ point seems to be that who we are, our selves or identities, is what our bodies do. In the Legion our body movements are defined from outside. In the dance, or in the legionnaires' off-hours, the men define their movements for themselves. The natives whom we see from time to time also define themselves. Given that our identities are what our bodies do, outside control of our bodies robs us of a personally generated identity, something Sentain has and something Galoup cannot tolerate. Galoup’s and the other men’s identities are imposed from outside by the Legion.

As for bodily movements, both the dance and the Legion’s push-ups are equally useless. But as between the two, dance gives pleasure. If you are to be defined by useless motions, at least let them give pleasure.

Denis herself seems to have escaped that kind of definition from outside. She quite avoids Classic Hollywood Style. Instead she shoots her film according to a script but then rewrites it in the editing room. She has created her own method of “shooting fast, editing slowly.” There is very little of shot-reverse-shot or master shot then closing in, very little dialogue, a great many quick, radical cuts, and a very jumbled time scheme. For Denis, it is the characters’ bodies that tell the story. Remember that Beau Travail begins and ends with a dance.

With dance, you are not controlled from outside. You can improvise, you make up your own moves, the young woman’s shimmy but particularly the break dancing with which the apparently dead Galoup ends the film. Denis has said, “If filming means you have to control everything, I‘d shoot myself.” Her style, then, is like an improvised dance. Get something on film—shoot quickly. Then sit down with a film editor and make up the film.

As for this film, I wouldn’t use my favorite term of praise and call it a masterpiece. I think it’s too jagged for that. But it is certainly one very brilliant film, deserving of all the praise and admiration it has received. .