BAY-bul or BAB-ble—you can pronounce it either way. One way, you sound learned in languages. The other way, you get “babble,” an appropriate pun in English, as though the deity who condemned us to a world of mutually incomprehensible languages had foreseen what would happen on radio stations that have to run 24 hours in the day.

In this film, González Iñárritu lives large—or wide. Babel has four plots taking place in four countries on three continents. It uses five languages: Arabic, English, Japanese (spoken and signed), Spanish, and snippets of French and Berber. This hugely ambitious film is the third in González Iñárritu’s “death trilogy,” after Amores Perros (2000) and 21 Grams (2003). By this third film, González Iñárritu had a $25 million budget, ten times the $2.4 million budget for Amores, his first feature film. No wonder he felt free to wander the planet. And Babel made $34 million in North America and $135 million worldwide, or why the movie business can be so profitable—if you hit it right. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and two nominations for Best Supporting Actress, but it won only for Best Original Score. It did score the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture—Drama and the Jury Prize at Cannes for Best Director.

Here are the four plots. All four involve, one way or another, children in danger, and González Iñárritu dedicated this film to his children:

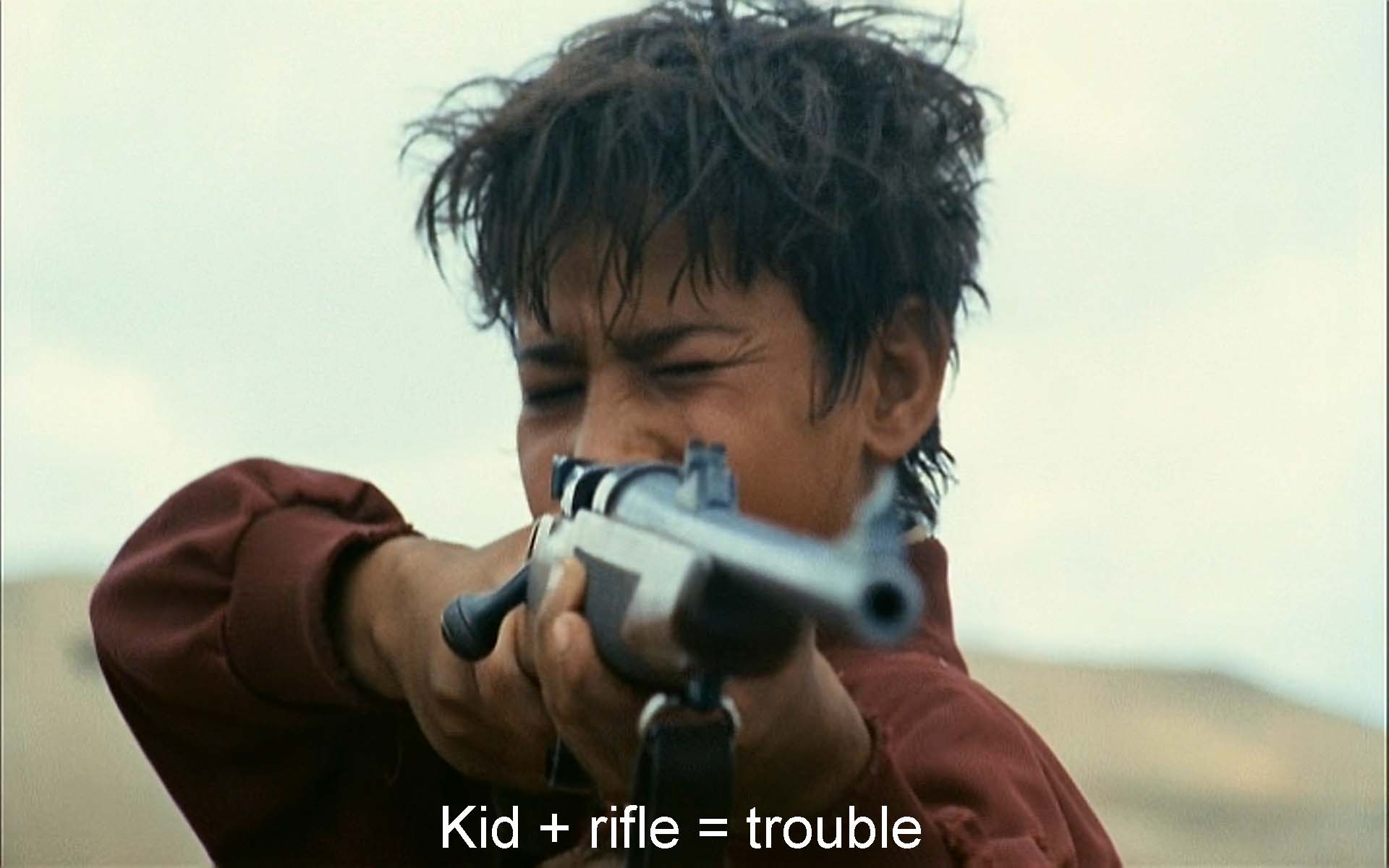

- A goat herder in Morocco acquires a high-powered rifle and entrusts it to his sons aged around twelve and fourteen. “A kid with a gun,” notes González Iñárritu, “is like gasoline and fire.” Together the kids and the gun ignite this picture.

- The younger of the two, testing the distance the gun can shoot, fires at a tour bus and hits an American tourist, Susan Jones (Cate Blanchett). The American authorities immediately assume it’s a terrorist attack, which the Moroccan authorities deny, stalling her removal to a hospital. (As a result Ms. Blanchett spends most of the movie lying in a stupor, rather a waste of her acting talent.) Richard, her husband (Brad Pitt) fights furiously to save her life.

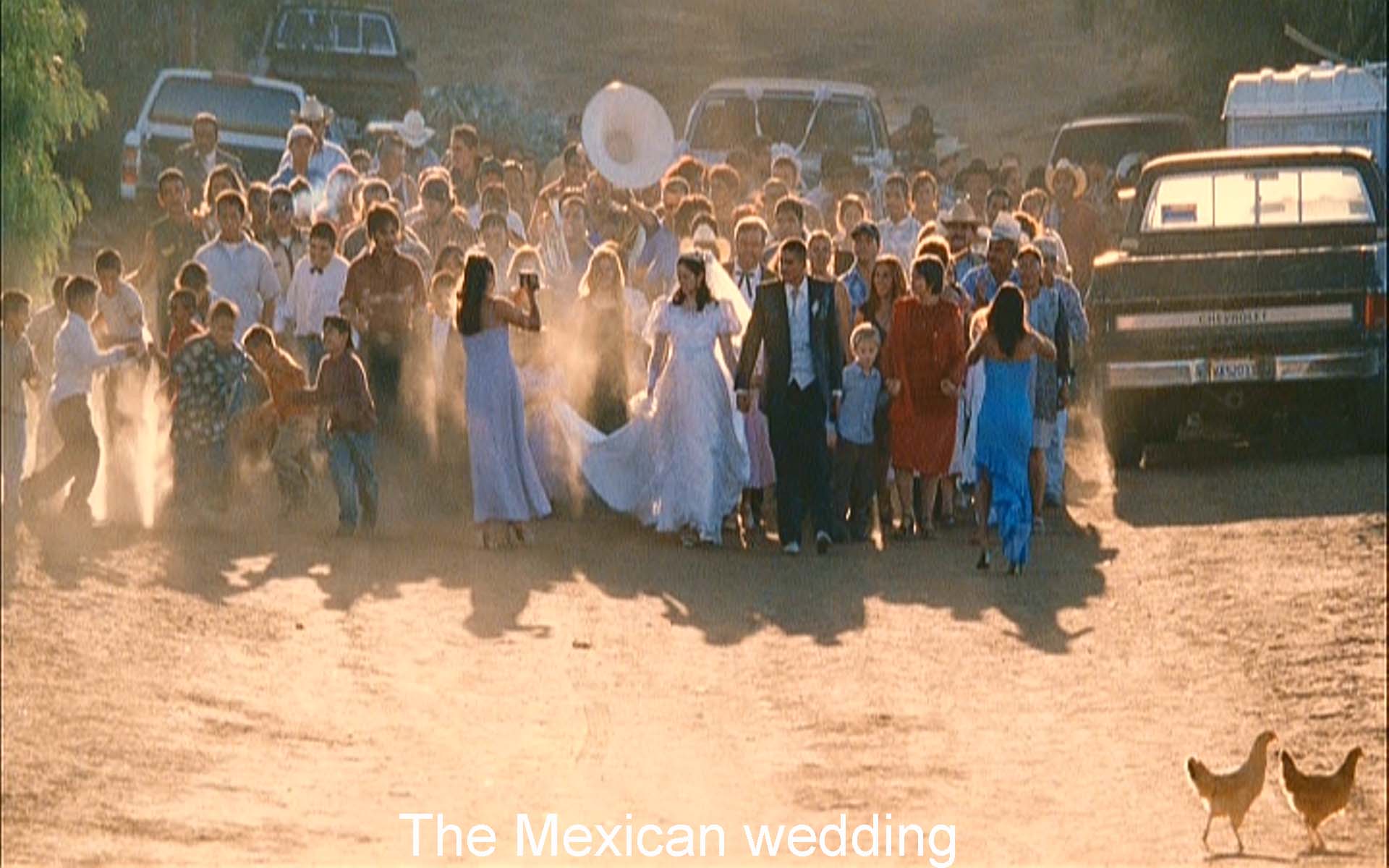

- Amelia (Adriana Barraza), a Mexican nanny in charge of the Joneses’ two children in San Diego, takes them to her son’s pleasantly dionysiac wedding across the border in Tijuana. The kids have a great time, perhaps their first experience of a culture radically different from their own. Amelia’s impulsive nephew Santiago (Gael García Bernal) is driving them home, but his drunken flight from the Border Patrol leaves Amelia and the two children dying in the desert.

- Cheiko, a deaf-mute Japanese teen (Rinko Kikuchi in a stunning U.S. debut), tries various sexual maneuvers to find affection after her mother’s suicide. She herself hints at suicide. As a snarky friend says, “She’s always in a bad mood, because nobody’s fucked her yet.” She’s working on that.

In González Iñárritu’s earlier films, he scrambled time. Here, he says, “In Babel the stories are just happening in parallel time.” That’s a technique as old as D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance of 1916. (There is a phone call early in the movie that seems out of sequence, but just that one scene.)

Incidents of intolerance tie together Griffith’s four plotlines. All four of Babel’s plots involve close calls with death, and in one the close call becomes fatal. Babel is the last film in what González Iñárritu’s calls his “death trilogy.”

Also it is death that begins the four plots. Susan’s and Richard’s baby died (SIDS?). That led them to take a trip to Morocco “to be alone” and to try to patch up their marriage, foundering because of mutual blaming for that death. And when Susan nearly dies, Richard’s fierce devotion brings them together again. In the Japanese plot, apparently the mother’s suicide led the father (Kôji Yakusho) to give up hunting and leave his gun in Morocco.

González Iñárritu has said: “In all the main characters of this film exists a feeling of anger and frustration that has to be redeemed through a connection established with the human body rather than with words. The only way we can really communicate is through touch. I am trying to emphasize . . . the hands or the glance which sometimes is our only way to build a bridge between one another.”

Touch means communication. Its opposite, absence, leads to disaster. In Morocco, the father’s sending his boys off on their own, with a gun!, causes all the trouble. Richard, confronted with the death of one of their children, “ran away,” and that has caused the trouble in his marriage. His sister-in-law in California can’t come to take care of the children, and that causes all the trouble in Mexico. The mother’s absence in Tokyo instigates her daughter’s sorry search for affection.

As a form of touch, González Iñárritu relies throughout on extreme close-ups. They let him develop character intensely, thanks to the amazing hand-held photography of his extraordinary cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto. In more imagery of flesh and the body, as worked out by set designer Brigitte Broch, the plots all share the color red. It shades toward umber in Morocco, primary red in Mexico, and pink or magenta in Japan.

Presence protects. Richard tries desperately to keep the tour bus there for Susan. Amelia tries to be with the children always. When she leaves them alone in the desert, they are terrified and disappear. Richard’s and Susan’s child died while sleeping alone. Cheiko’s mother died alone. Distance is dangerous and illusory: the gun can hit something three kilometers away—unfortunately.

Bodies touching unite and protect. Conversely, in all four of these plots, language creates divisions. The American tourists speak no Arabic, rendering them helpless and fearful. The Border Patrol doesn’t speak Spanish. The Japanese teen is a deaf-mute. And González Iñárritu demonstrates the ultimate futility of words on us his audience: the teen gives a policeman a farewell note which he reads onscreen, but he doesn’t let us in the audience learn what it says.

But this is a film not just about the barrier of language (the Tower of Babel story from Genesis 11:1-9). It looks at all barriers, especially the boundaries that separate nations and nationalities. All these boundaries involve the police. In Morocco, they shoot down supposed terrorists. In the U.S., they deport poor Amelia. In Tokyo, they investigate the teenager’s father. But in the final plot the Japanese policeman shows a fundamental decency that redeems him and the nubile, suffering teenager who tries to seduce him. The bad guys in this movie are those who break human connections: the Border Patrol; the selfish tourists who want to desert Susan and Richard; or the teenage boy who dumps Cheiko.

Babel explores metaphorical boundaries as well, like the line between teen and adult or inhibitions on sexuality and money. All the characters cross or try to cross these boundaries in a literal, bodily way. And all come close to the ultimate boundary, death. One crosses it. Susan, Amelia, and the two children nearly perish. The mother in the Japanese plot has died, her teenage daughter contemplates suicide, and the boy Ahmed in Morocco does cross and die.

Babel has incidental images of crossings: the boys trying to shoot three kilometers away; the teenagers in Japan hitting a volleyball across the net; the telephone from Morocco. There are crossings of what we might think of as sexual taboos: Richard’s kissing Susan while she urinates, the younger boy peeping at teenaged Zohra in Morocco—his father seems to think that as bad as the near-fatal shooting. Cheiko exhibits herself in Tokyo, and we in the audience peep at her nude body as the Moroccan boy peeped at teenage Zohra.

One could, and at least one review does, criticize this film as involving “cheap ironies and rigged coincidences.” But González Iñárritu is not showing us coincidences. Rather, he is tracing perfectly logical causalities, in particular, how the Japanese father’s gratefully giving his gun to his Moroccan guide triggers (no pun intended) Susan’s near-death and most of the other troubles. González Iñárritu is showing how we live in a web of interconnected causality, even from opposite sides of the globe.

In Babel González Iñárritu gives us another element in his worldview. For him, the central relationship on earth among humans is between parents and children. For all its intercontinental shenanigans, Babel is a movie deeply involved with closeness between human beings. All four plots end in touch—embraces. The Moroccan father clutches his dead son. Richard and Susan embrace, and Richard embraces the tour guide (a parent like himself) who has seen him and his wife through their ordeal. Amelia’s son embraces her. These final hugs are between parents and parents or parents and children, although one, from Casablanca to San Diego, has to be by telephone. These embraces culminate in the final shot, Cheiko and her father hugging, and then the camera pulls back to show us vast, sprawling Tokyo, hundreds of nightlit windows with millions of stories behind them, a true skyscraping Tower of Babel.

Obviously, perhaps too obviously, González Iñárritu is demonstrating a worldview. All his characters are connected, no matter how separated they are geographically. We live in a global village or at least a global city, as in the final shot. But we are connected through misfortune, near-death, and death itself. In other words, González Iñárritu has given us a fine meditation on the global village that ties our interconnectedness to the mortality and fallibility that we all share. And that was the point of the Babel legend, wasn’t it?