Sarah Polley was only twenty-seven when her astonishing debut film Away from Her opened at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2006. She was adapting (and got an Oscar nomination for her adaptation) a short story by Alice Munro (who would win the Nobel in 2014). The story was “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” which appeared in The New Yorker in 1999. Polley has written (for a post-film re-issue of Munro’s story) that she was deeply moved by it. “This might actually be the only love story I've ever read. The only true love story,” she said in an interview with Scott Macaulay.

In linear form, the film's love story goes this way:

Grant and Fiona (Gordon Pinsent and Julie Christie) have been married for more than forty years. A professor of literature, he had a number of affairs with students twenty years ago (as did his colleagues), but he repented. He retired from the university, promising Fiona a new life. They live in her parents’ cottage by a lake, happily reading to one another and cross-country skiing in the Canadian winters.

But Fiona is slowly dementing. She realizes that she must go to live in a nearby home, Meadowlake (sic), but Grant cannot face this. She prevails, however, and moves in. Meadowlake has a rule that a new resident must get no visits or phone calls from the relatives she is leaving behind for thirty days. Grant reluctantly and with difficulty complies.

When the month is up, he finds that Fiona no longer recognizes him. Instead, she has adopted a mute, wheelchair-bound resident, Aubrey (Michael Murphy), mothering him. Aubrey’s wife Marian (Olympia Dukakis) had parked Aubrey there while she went on a trip. On her return, she takes him back to their house, and Fiona collapses into depression.

Grant tries to get Marian to bring Aubrey back to Meadowlake, but she refuses. The two of them begin a sexual relationship, however, perhaps for ulterior reasons. Grant hopes to persuade her to let him take Aubrey back to Meadowlake. She perhaps hopes that she will not have to take care of Aubrey at home. Marian moves in with Grant, and she lets Grant take Aubrey back. But Grant finds Fiona temporarily improved, recognizing him and remembering a little.

This film is anything but linear, however. For one thing, we see everything from Grant's point of view. For another, there are three regions of time. In the present, Fiona has moved to Meadowlake. She has lost most of her memory and is mothering Aubrey. Grant is calling on Marian to persuade her to take Aubrey back to Meadowlake. In the recent past, Grant and Fiona were living in their cottage, reading and cross-country skiing, but she had begun to lose her memory. She moved to Meadowlake and took to mothering Aubrey. Then Marian took Aubrey home. In the remote past, Fiona’s parents emigrated from Iceland to the cottage she shares with Grant; Fiona dated a boy one summer who may or may not have been Aubrey; Grant and Fiona were about to take a ferry when she proposed to him; Fiona learned she could not have children and adopted two dogs; Grant had affairs with the “sandaled” young women in his classes; he left the university, and gave Fional “a new life” in the cottage. The film pivots on present time. It flashes back again and again, but slowly brings out the recent and remote past and develops the present relationship between Grant and Marian, the relationship that develops the film’s major theme, fidelity.

Marian is tough-minded and a bit contemptuous of Grant’s susceptibility to the “noble” deed of bringing Aubrey back to Fiona. “What a jerk!,” she says after they first meet. Throughout, the women are wiser than the men. Fiona recognizes that she has to go into a home and pushes Grant into accepting that fact. Meadowlake supervisor Madeleine (Wendy Crewson) uses her rules to bring Grant to reality. Nurse Kristy (Kristen Thomson) helps him adjust. And Marian finds a way to do the right thing for Aubrey. He, however, is inert throughout, and Grant is deeply into denial, at least in past time.

This film insists it is Canadian with lots of little touches: place names, chain store names, a Maple Leafs hockey match, and the occasional “aboot” and “oot” (contrasted to Marian’s strong American, perhaps New York, accent). Canada implies cold and snow, lots of snow. We see Grant and Fiona bundled up, skiing away. An interesting contrast to their boots are the “sandaled” students Grant has affairs with—they are “hot”?

Few scenes do not have snow in them, but one such scene stands out. Grant and Fiona have gone for a walk in a nearby conservation area (“conservation” of memory?). She comes upon a cluster of bright yellow flowers, skunk lilies, and she bends down to touch them. She reaches inside the petals and feels the heat of the blossom. “I can’t be sure if what I’m feeling is the heat or my imagination.” (Later, she remembers this episode and carved skunk lilies will adorn the sign identifying her room.)

At the outset, Fiona is associated quite literally with warmth: she makes the fire at the house and she puts a frying pan away—but in the freezer. She had “the spark of life,” according to Grant. At Meadowlake. warmth turns figurative as we see the various characters. Madeleine the supervisor is institutionally friendly—cold, while nurse Kristy is truly warm, helping patients and their families. One female patient at Meadowlake flirts with Grant—warm. Grant warms up the adolescent Monica who finds the place “fucking depressing.” Grant tries unsuccessfully to warm up Marian, but the ultimate warming is Marian’s warming up Grant. That culminates in the scene with them in bed together. (It parallels an earlier scene of Grant and Fiona in bed).

That warming up began with a message on Grant’s answering machine, just as this film originated in words, Munro’s words. Words as such occur again and again in the action. Grant is a professor of (apparently) mythology—words that are by definition untrue. Robert McGill has identified a variety of literary references: “Nurse Kristy reads to Aubrey from Alistair MacLeod’s novel No Great Mischief, while Grant reads to Fiona from Michael Ondaatje’s poem ‘The Cinnamon Peeler,’ and later from W. H. Auden and Louis MacNiece’s Letters from Iceland. Indeed, a passage he reads aloud from Auden’s poem ‘Death’s Echo’—one which urges the reader to ‘dance while you can’ —implicitly licenses Grant to dance with Marian both literally and figuratively soon afterwards”.

Less literarily, Fiona reads to Grant from a book on Alzheimer’s. Nurse Kristy recalls a church sign that said, “It’s never too late to become what you might have been,“ a line that—perhaps—licenses Grant’s affair with Marian. One of the residents at Meadowlake is a play-by-play commentator on hockey games and describes even his own walks through Meadowlake.

Polley’s calling attention to words this way may explain a very curious detail that she created. It isn’t in Munro’s story. Fiona recalls a story Veronica, a long-ago girlfriend of Grant’s, told her about German soldiers patrolling in Czechoslovakia during World War II. “She told me that each of the German patrol dogs wore a sign that said Hund. Why? said the Czechs, and this Germans said, “Because that is a Hund.” But surely the important thing is not the story, but Grant’s affair with Veronica and Fiona recalling this (but not other, pleasanter things) and now his being made visibly nervous by Fiona’s recalling the affair. These matter, but instead we get this odd anecdote about an unnecessary word.

Words accompany the journey which is life, the way Hund pointlessly labels the dogs. Words go alongside life, not changing anything—only actions change things. Words make a play-by-play commentary, which may well be superfluous. (Not very complimentary to Munro or literature, but then Polley is a filmmaker.)

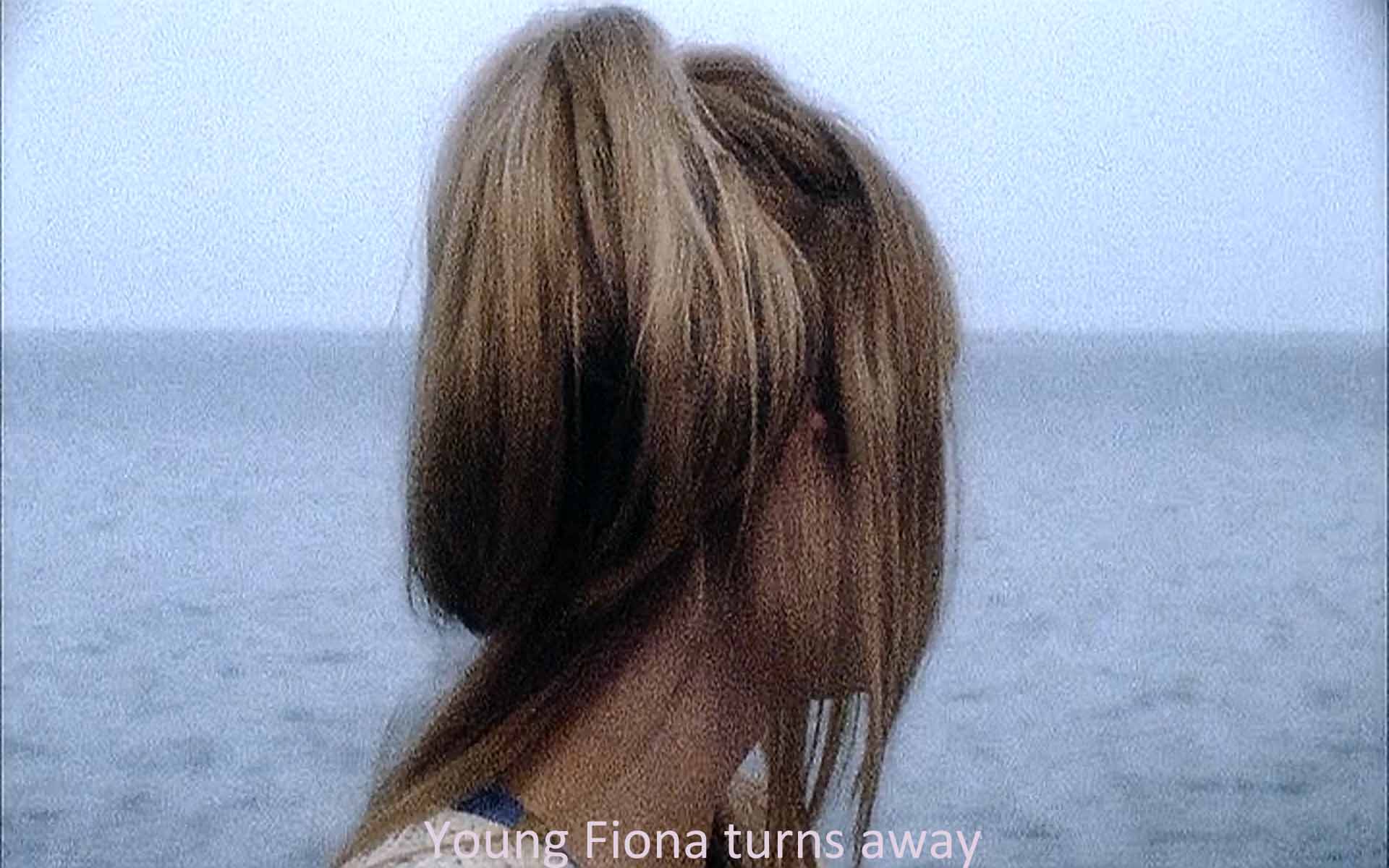

And life is a journey. That is one of the great metaphorical systems in Western culture, and Polley uses it to the fullest in Away from Her. I’d say the word that describes her theme is “going.” As Fiona says, “I’m going, but I’m not all gone.” The action as a whole tells of Fiona going away from Grant, although, he says, “I never wanted to be away from her.” The opening shot shows Grant going to Marian’s for the first time. The closing shot shows Fiona, aged eighteen, turning away (going) by Lake Huron where she and Grant long ago were about to take a ferry and where she proposed to him. We get many, many shots of cross-country skiing. The parallel tracks suggest Grant’s and Fiona’s forty-plus years of “going” together; the scene where Grant’s tracks are at right angles to hers perhaps suggests the time when he was having affairs.

As her dementia progresses, Fiona’s “going” becomes a directionless wandering. She gets lost in the woods and Grant finds her on a (symbolic) bridge. Grant tries to get her to recognize the home where they have lived for twenty years, but she cannot. Her last move is from the first floor at Meadowlake to the second. And then Marian moves (goes) from her house to Grant’s. (I assume; this is not in Munro’s story.) Grant drives back and forth to Meadowlake and to Marian’s again and again. Finally he drives Aubrey to Fiona at Meadowlake. Everyone is “going” —living.

Iceland enters the movie via Auden and MacNeice’s Letters from Iceland, and Polley gives us some found footage of that island’s fabulous combination of cold snow and hot volcanoes. Fiona’s ancestors emigrated from there, and Grant used to teach its myths. As he and Fiona talk about Iceland, Grant recalls, “You always said, there ought to be one place you thought about and knew about and maybe even longed for—but never did get to see.” Iceland is that place, an island that is constantly remaking itself, a place that is beyond poor Fiona in her demented state. Instead, the strange new place is the one Marian and Grant have gotten to: she has moved in with him perhaps so that she can put Aubrey permanently into Meadowlake. This is at best implicit in Munro’s story, but Polley spells it out. All the “going” has come to this strange place, and we are all constantly re-making ourselves, like Iceland.

Marian has redefined fidelity; so has Grant. As matters end up, the highest fidelity is Grant’s infidelity with Marian and her infidelity with him. Both are still married, as she reminds him, but they do the best for their spouses by allowing Fiona and Aubrey to continue their own infidelity at Meadowlake. The film is paradoxical. Fidelity is infidelity, not the kind Grant carried on with the students, something altogether different, even “noble,” as Grant and Marian first call it.

Curiously, all three of Polley’s films (as of 2014) deal with infidelity. As her last, autobiographical film (Stories We Tell, 2013) shows, her own family, indeed her own parentage, comes from infidelity. It would be interesting to speculate how this works into her two earlier feature films—but it would only be speculation and unseemly at that. I’ll just say that this, her first feature film, makes an extraordinarily subtle and paradoxical point about infidelity, one that turns one’s usual notions inside out and upside down. No wonder the critics all say how “promising” this film is, how it augurs great films to come. But I’d say at least one of those great films is already here, Away from Her.

Items I've referred to:

Macaulay, Scott. “Speak, Memory.” Filmmaker - the Magazine of Independent Film 15.3 (Spring 2007): 34-39.

McGill, Robert. “No Nation but Adaptation: ‘The Bear Came Over the Mountain,’ Away from Her, and What It Means to Be Faithful.” Canadian Literature/Littérature Canadienne 197 (Summer 2008): 98-111, 200.