Most critics see this first film by Jean Vigo as his finding his unique and witty style by making a documentary about the city of Nice with a certain political point of view. This film is surely that. We get shots of the city, the idle rich idling, and the anything but idle workers. But we also get the cemetery statues, and the eternal sea, and a lot of shots up the skirts of some young women dancing. A lot of the film, it seems to me, doesn’t answer to a political interpretation.

I think there’s a rather different way of reading it. The famous French critic André Bazin spoke of Vigo’s “almost obscene appetite for the flesh.” I think we could interpret Vigo’s theme as the old Biblical curse on Adam: work and death (at least for male human flesh). In a way, this film plays a theme and variations on the French word fin or its English equivalent end. Both words have a double sense: termination, things finishing but also a second sense, aim or purpose, as when I say I work to achieve a certain end. We have to die, end, and we must work; we must have some purpose, some end.

The opening shot is of fireworks: BOOM! and it’s over. This is perhaps the last time we see a fully completed action. Other endings are less final. Cut to aerial shots of Nice, especially the sea and the marinas. Then two tiny tourist dolls get off a toy train and an invisible croupier’s rake pulls them onto a roulette table. Then, les jeux sont faits, and they go we know not where.

More shots of the sea and city: motion without end in either sense. Some workers clean the sidewalks. Other workers carry on their jobs aimed at entertaining the tourists, setting up tables, painting the carnival figures—repeating their jobs “without end”—at least we don’t see them conclude with their function fulfilled by tourists eating breakfast or walking, at least not yet.

He gives us shots of buildings and sidewalks whose end is the walkers endlessly walking along the Promenade des Anglais. Newspapers—endless? A cameraman films, but we do not see or know his film. Vigo’s fast motion gives the scene a jittery futility aided by the incessant accordion music added to this silent film by Marc Perrone. A garbage man and a beggar woman do their things—which never end. And the tourists, endlessly walking or endlessly sitting. In one of Vigo’s comic touches, he gives us one brief shot of an ostrich watching all this purposeless activity.

Then we see a series of the most flagrantly endless images, images that, for me, set the sans fin or endless theme for the whole documentary. A seaplane that does not lift off. Racing boats that do not cross the finish line. One side of a tennis game. Men playing pétanque, but we do not see where the boule lands. A racing car that does not cross the finish line. Limousines that drop off elegant women to go who knows where.

More activities follow, endless in both senses: tourists sitting; tourists reading newspapers; shore birds assembling; tourists dozing in the sun; street musicians being ignored; finally the legs of the sleepers, legs not being used for walking or anything, just being tanned. Then one of Vigo’s comic bits: a woman’s clothes changing and changing until she is nude—ah, there is an end, nothing further. Later there will be another such parody shot: a shoe shine rubbing down to the bare foot. Vigo is exposing these people! But they expose themselves on the rocky beach, tanning, throwing a ball, even swimming. One man tans himself until he turns black. Buildings sit in the sun with their Art Deco facades. Alligators bask in the sun.

Then Vigo cuts to an altogether different kind of building: shots up between crowded apartment buildings—the workers’ homes. We see women doing laundry that one must do over and over. There is no end to laundry, alas. Workers carrying food pans on their heads look like Chinese coolies; workmen shoot craps and play some kind of hand game like rock, paper, scissors: The lower classes amuse themselves as the upper classes do. Cut from the workers to dancers in evening dress, and we do not see the dance end. It’s not just the upper classes who do purposeless things, the workers do as well.

Now Vigo takes us to Carnival in Nice, and here again we get the ideas of ends and endlessness. Carnival marks the beginning of Lent and the ending to a gay and playful time when these people are allowed to eat meat and play around, although I suspect few observe such old-fashioned religious rituals. Vigo has fun with the gigantic heads being paraded and the costumes and masks and flowers being thrown—no end to these, and no end to the labor of painting and picking them. And inside, carrying the huge masks: workers.

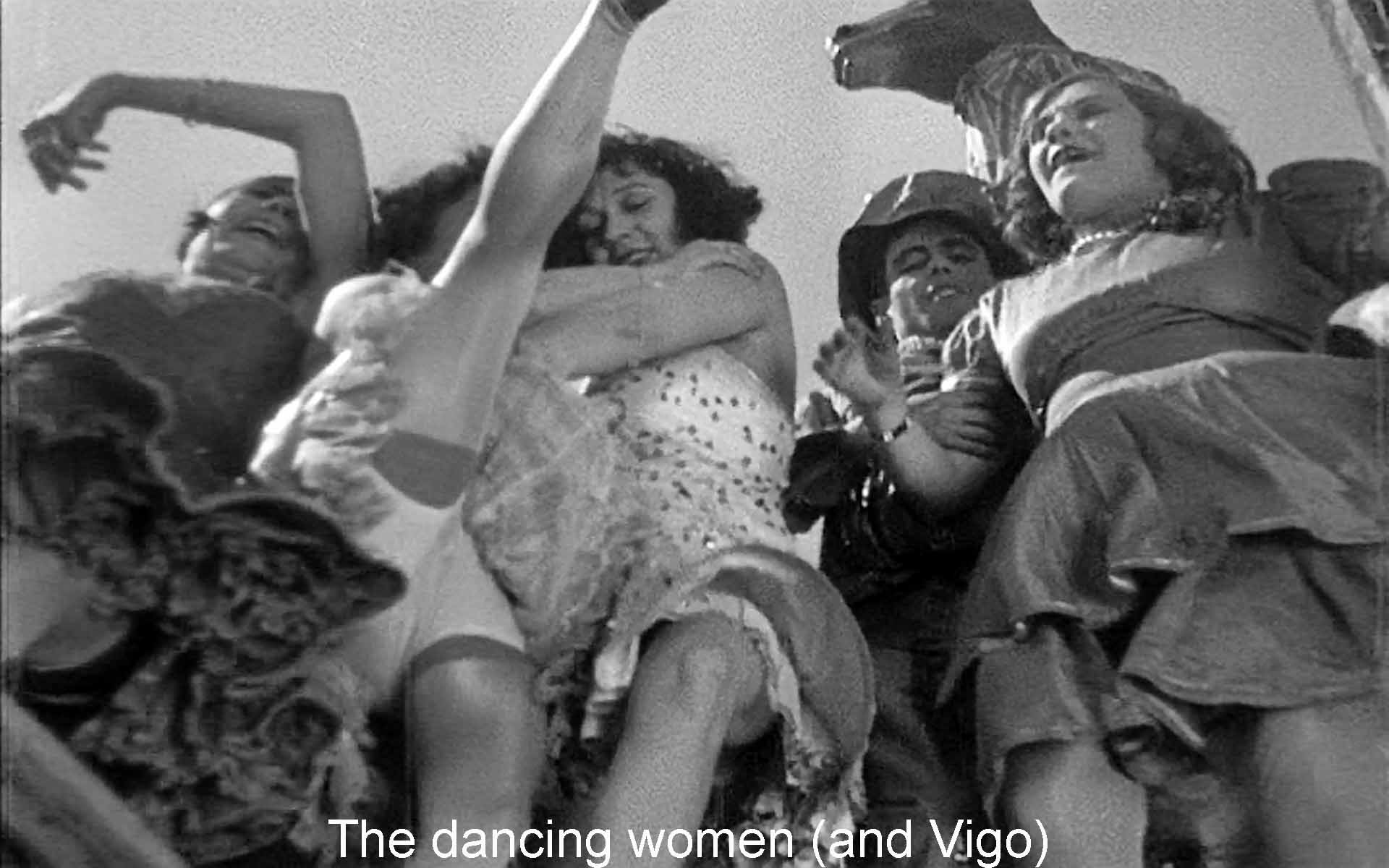

Vigo then gives us a shot that will recur to the end of the film, a shot up the skirts of some young women dancing on a platform, a kind of jiggling dance on and on with equally jiggly music. But cross-cut with the dancers Vigo gives us a military officer riding, a military parade, cemetery crosses, warships (?) in the harbor—the serious things of life and death—a priest who is the sign of disapproval of the dancing (and Vigo’s shots) but only the sign; it doesn’t happen. Then Vigo cuts to a funeral procession in the street (a painful contrast to the frivolous carnival parade and the military parade). It represents an end, surely, but it is also a procession whose end we do not see.

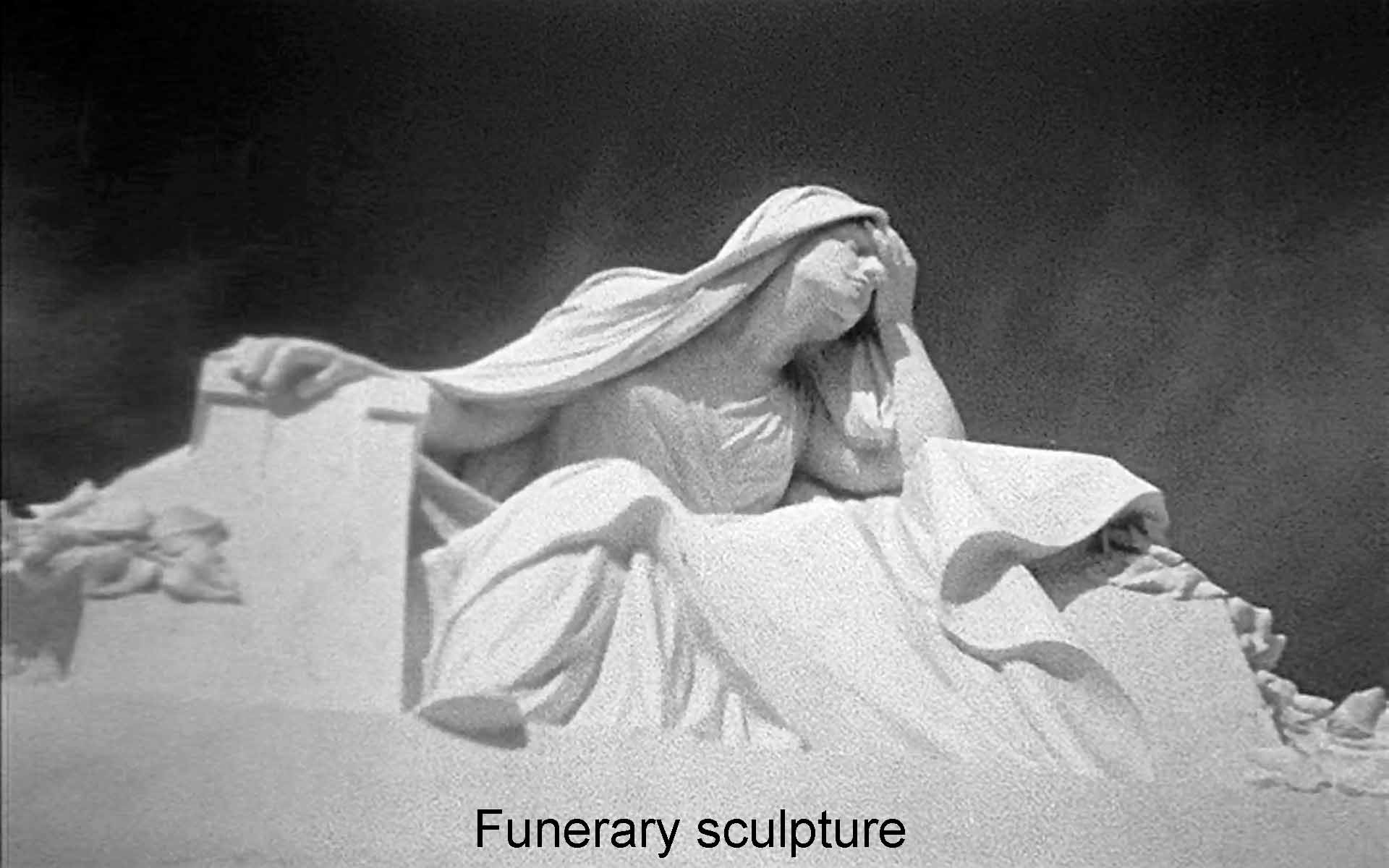

Back to the tourists and an officer with medals and a joke shot of the shoeshine down to the bare foot, a joke surely, but cross-cut with cemetery art a reminder that we are all flesh. He follows it with a shot up the pants and skirts of people walking over a manhole. Then back to the dancing girls. A man works on his abs—more flesh. Vigo makes a bawdy joke with the crotch of one of the statues, reminding us, me anyway, of the shots looking up the dancers’ skirts.

This flamboyant series of rapid cuts from the first shot of the dancing girls to the end of the film—I counted thirty-five— deserves a shot-by-shot analysis, but this is not the place for it. Some motifs are clear: the contrast between the dancing, jiggly girls, flesh, sex, opposed to the solemn stillness of the cemetery statues and the eternal sea and trees. Shots of sea, sky, and trees remind me, in this context of birth and death, of the long cycles of nature as opposed to the jittery, purposeless activities of the tourists.

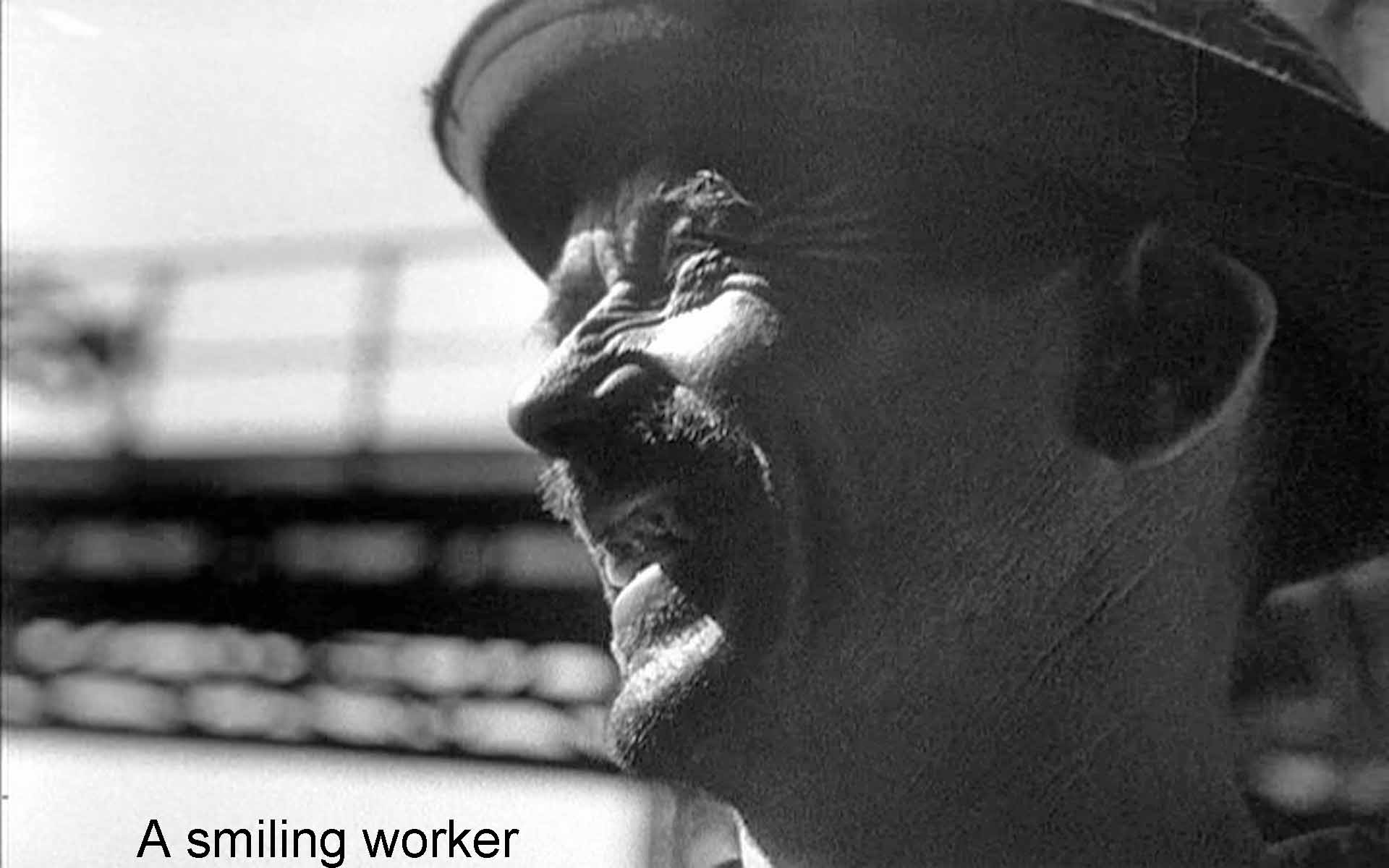

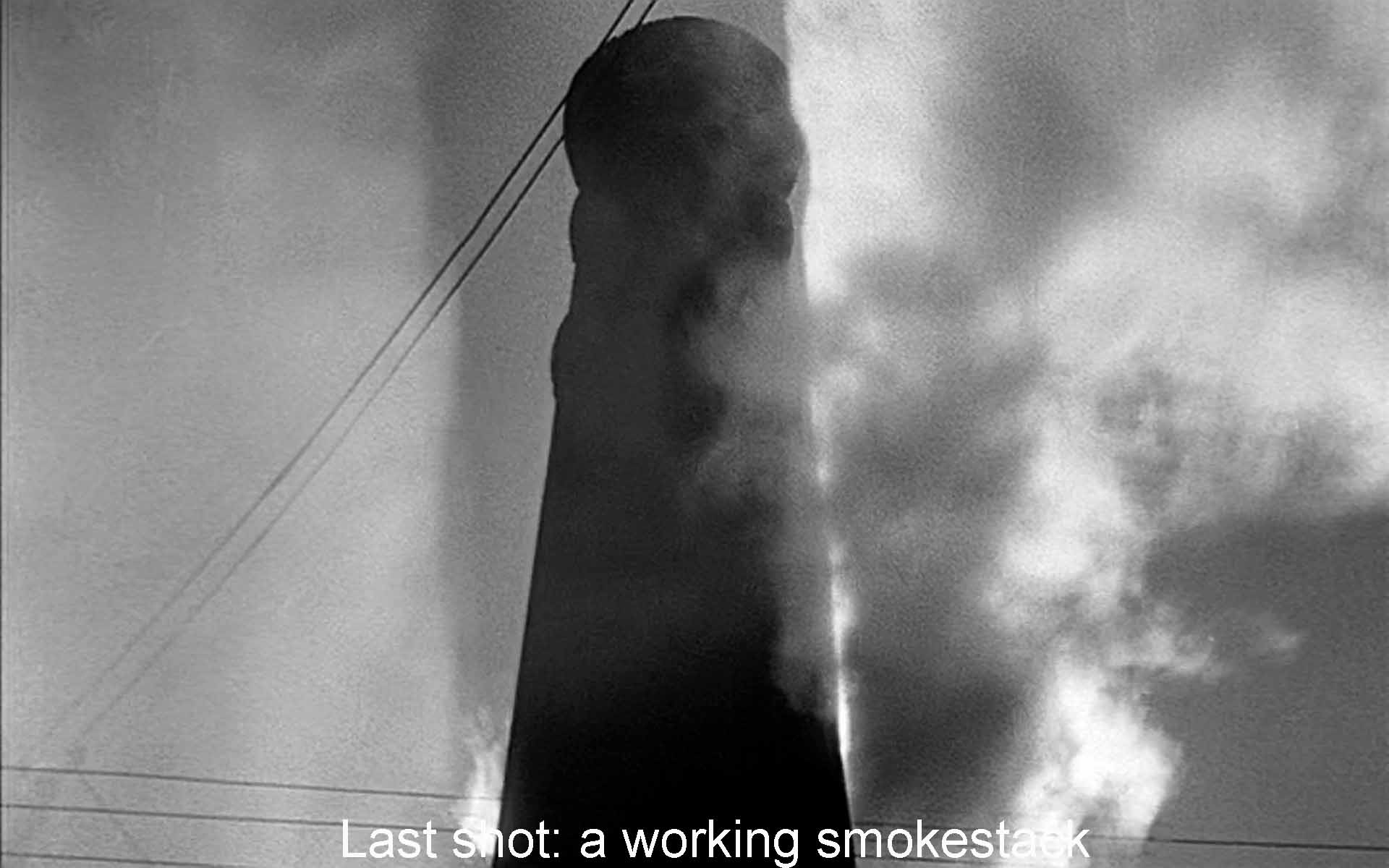

A break in this pattern comes with the first appearance of a factory smokestack, this time with no smoke coming out of it, contrasted with a chattering older woman. Then Vigo shifts to factory chimneys that do have smoke coming out—purposeful activity. And we see laughing workers. One man shovels coals into a blazing smelter, purposeful activity. The closing shot shows a furiously smoking smokestack, presumably purposeful, certainly a contrast to the quick, purposeless flash of the fireworks in the opening shot. Vigo has contrasted the first part of the film, the aimlessness of touristy Nice, with, in the ending, the purposeful activity of workers and their glee at the transition. Even the chattering woman seems pleased.

Many critics write off á propos de Nice as simply Vigo’s freshman effort, inventive, witty, but ultimately a simplistic political documentary. I find that reading unsatisfactory, given the cemetery statues, the funeral procession (a comment on the other parades), shots up the dancing girls’ skirts, as well as the frankly humorous shots of the tourists endlessly walking and sunning themselves. I think Vigo was developing his witty, pararealistic style to a more serious fin or end, and the result is a film I can genuinely admire.