To many, this seems Fassbinder’s most accessible film. You can read it quite simply as just a social tract against racial discrimination and the economic oppression of the poorest members of world society. Imagine it, though, if a 1950s Hollywood director had made this story with Sidney Poitier and an aging Barbara Stanwyck. How soft and slick and shiny it would be, and how hard and strained this film seems, with its odd, off-key camera work that links it to the rest of Fassbinder’s films. In fact, this film loosely follows Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1956), a prettied-up story of an older widow (Jane Wyman) and an unsuitable marriage (to Rock Hudson as her gardener). Some current critics claim that Sirk was burlesquing 1950s Hollywood style by overdoing it. I don’t see that. I think he was just making pop movies the way Hollywood was making them in the ’50s. Nevertheless, Fassbinder learned something from Sirk, a special kind of tenderness. And Fassbinder’s film is much grittier.

Emmanuella (Brigitte Mira), a fifty-plus widowed cleaning lady, takes shelter from the rain in an all-Arab bar in Munich. That is, the only patrons its shabby blond owner (Barbara Valentin) and accompanying hookers welcome are the ausländer, foreigners, or gästarbeiter, “guest” workers, imported from Arab or other impoverished countries to work in a Germany whose own workers are too well-off to do the least desirable jobs. (Shades of 21st-century U.S.A.) To insult her, one prostitute gets one of the men, Ali, a Moroccan (El Hedi ben Salem), to ask her to dance. They talk and have a drink. She learns his long Arabic name, his real name, for “Ali” is to these workers what “Paddy” or “Sambo” or “Miguel” would be for similarly imported workers in the U.S., an epithet for any of them. He walks her home. She invites him up. The last streetcar is leaving, so she fixes him a bed. He can’t sleep and comes into her room to talk . . .

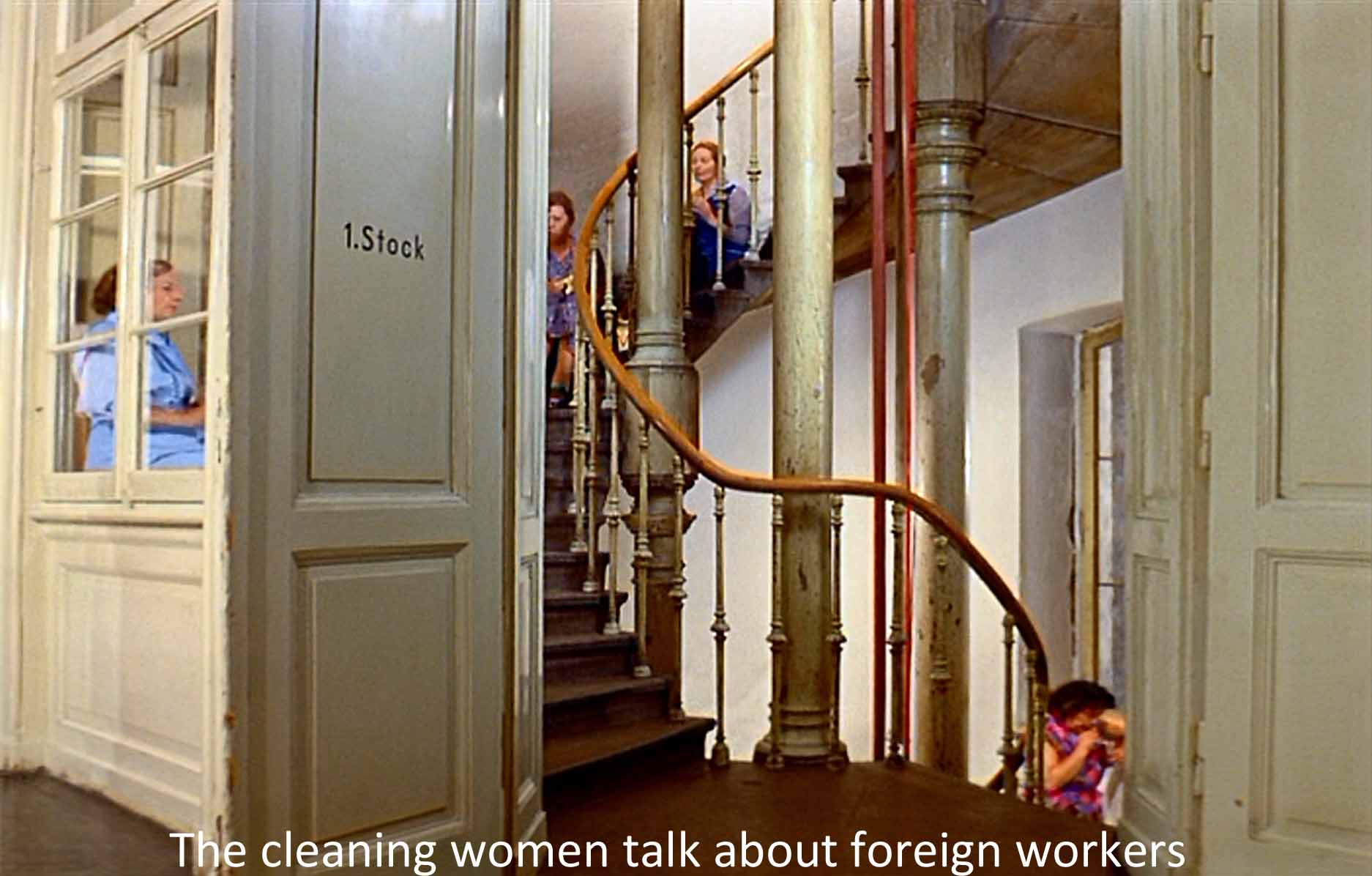

The next morning, after her initial shock, they embrace lovingly and talk (he giving the title of the movie in his pidgin German). Tenderly they part (under the spying eye of the nasty concierge [Elma Karlowa]), he to the auto repair shop where he works, she to learn from the other cleaning ladies how they and all right-thinking Germans despise these impoverished Arab (black?) workers. (They are just gossiping; they don’t know—yet—about Emmi and Ali.)

She tries to tell her daughter Krista (Irm Hermann) and her loutish son-in-law Eugen (Fassbinder himself) that she has fallen in love, but they just think she is crazy. That night, Ali is waiting outside her apartment, and with a pair of simple “Ja’s,” he moves in.

When the landlord’s son (Marquard Bohm) tries to evict Ali as a “lodger,” Emmi announces they are going to get married. Ali, to her surprise, enthusiastically agrees. They do, celebrating with an expensive dinner in a restaurant where Hitler used to eat. Then they tell the children. Her son Bruno (Peter Gauhe) is so furious he kicks in the television set, but the others content themselves with curses.

The neighbors harass the newlyweds, accusing Ali of being dirty, calling the police because he has his workmates home and they play Arabic music. The grocer refuses to serve him. Emmi’s fellow cleaning ladies shun her when they learn about Ali. The waiters in an outdoor cafe stare at them. The couple decides to escape by going on a holiday.

When they come back, things suddenly, if crassly, get better. The grocer decides he needs her trade. A neighbor lady wants her cellar storage space. Bruno wants her to babysit while his wife works. Her fellow cleaning women have a new, Yugoslav worker they can look down on. Indeed Emmi shows Ali off to her friends, and they admire Ali’s muscles and murmur, “How clean he is!”

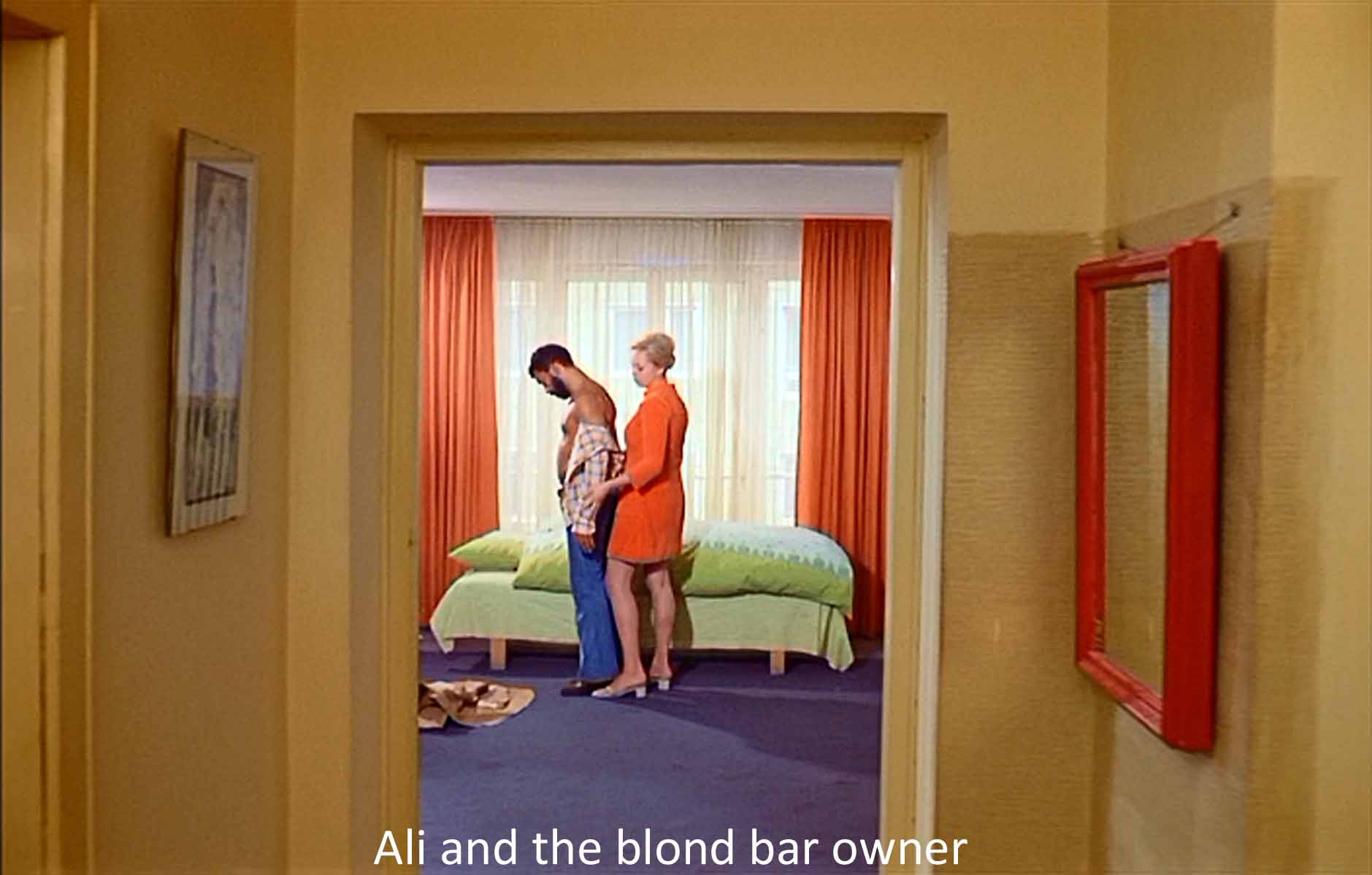

Ali, annoyed at being displayed like a boy toy, returns to the original bar and the overblown blonde who owns it. She can give him the couscous Emmi refuses—and incidental sex. Finally, he leaves Emmi entirely. When she comes to the garage to plead with Ali to come back, he joins in his mates’ cruel laughter at “his grandmother from Morocco.” Finally, as he is gambling his money away in the bar, she comes in, and he invites her to dance, as he did when they first met.

As they are slow dancing and making up, however (“Together we are strong”), he collapses in agony. At the hospital, a doctor tells her he has a perforated stomach ulcer, an illness common among imported workers because of the tensions under which they live. He will have this operation, six months later another, and so on. She promises zonked-out Ali that she will do her best for him.

You and I can read this simply as a sentimental example of the evils of racial and economic oppression, but that would leave out the Brechtian, alienating feeling people get from it. The film is complicated by the way the relationship between Ali and Emmi changes in the second half, after the outside pressures relax a bit. Now the contradictions within the relationship come to the fore. He is young and virile; she is an old woman. But she is German and he is a “neger.” She can show him off to her mates as if he were a purchased slave. Fassbinder leaves us with an open ending. We don’t know how this relationship will play out. But nothing good is going to happen—as though Fassbinder is saying, even love involves a power imbalance that will eat away at the relationship. As he said in his famous essay on Sirk, “After seeing Douglas Sirk’s films I am more convinced than ever that love is the best, most insidious, most effective instrument of social repression.”

The complication in the relationship makes this a richer, subtler film than, say, Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows. Even more enriching is Fassbinder’s extraordinary camera work that lead into larger themes. Chris Fujiwara, in a fine essay about this film, notes a recurring visual motif: “a wide shot revealing the emptiness around the couple appears at moments when Emmi and Ali are most together.” It dramatizes in visual terms the isolation and hostility the couple suffers.

Another motif: over and over again Fassbinder shoots through a door ajar, a window, an archway, up the turns of a winding staircase, down a corridor, the length of a room. Repeatedly characters in the background of the picture stare motionlessly at the principals in the foreground. Fassbinder seems almost to struggle to get his picture, reaching along a table or a bar or up a stairwell or past a shoulder to get deep into the focal range of his camera. He shoots the gaiety of Ali and Emmi’s wedding supper through a funereal doorway. He shoots a long sexual sequence between Ali and the blond owner of the bar through a doorway in her apartment.

In general, a great deal of the action takes place around doors: the door to the Arab bar, to Emmi’s apartment building, to the city hall, to a telephone booth, Hitler’s restaurant, the blonde’s apartment, the office where Emmi cleans, the garage where Ali works (including a doorless car), to the hospital ward, and so on and on. In the opening shot Emmi comes through the door of the bar, and the whole opening sequence proceeds as a series of entrances by Ali: first, to Emmi’s apartment building, then her apartment, then her bedroom, finally her.

It seems to me that the film is defining human relationships as, quite literally, penetrations: entering—or being taken into—the space of another. That’s what these guest workers do—they enter Germany.

Relationships take place around eating and drinking, that is, things entering the body. Ali and Emmi first meet over drinks in the bar. Then she takes him home and feeds him. The next morning she crows: “I’m a really good cook.” The cleaning ladies discuss their business while eating their bag lunches on the stairs. Emmi has her discussions with the landlord and the grocer while surrounded with food or drink. Ali virtually equates couscous with sex with the blond. They gamble and celebrate the wedding (both involve “taking a chance”) with food at the bar. Ultimately Ali’s perforated ulcer images both the penetration and the eating. It acts out on his body his statement (in his poor German), “Fear eats the soul.”

The opposite of this penetration is distance, often established by characters staring or glaring (particularly from the depths of the frame toward the principals in the foreground). For example, the Arabs in the bar stare when Emmi first enters, a scene mirrored later on when Germans stare at Ali and Emmi in a sea of yellow chairs in an outdoor cafe. The cleaning ladies first move away from Emmi, then in a later scene from the Yugoslav. The neighbors stare at Emmi and Ali on the stairway (twice). The waiter in Hitler’s restaurant stares, as do the angry grocer, Emmi’s assembled children, and Ali’s workmates when she comes to his garage.

Fujiwara makes an excellent point:

There’s a sense throughout the film that the world has become still-a feeling of timelessness, conveyed not just through the long, strange moments of silence and immobility, but also through the way the characters of Fear Eats the Soul constantly generalize about life. “Fear eat soul” (a closer translation of the film’s ungrammatical German title, Angst essen Seele auf). “Time heals all wounds.” “Money spoils a friendship.” “In business you have to hide your aversions.” “Half of life consists of work.” “Germans with Arabs not good.” “Think much, cry much.” “Dark clothes look so sad, don’t they?” “It’s no fun drinking alone.”

A special kind of staring has to do with mirrors. Emmi gets up after her first night with Ali and stares at herself in the mirror. At various points in their relationship, he stares in the mirror. The blond bar owner comes home from a day’s work and stares at herself in the mirror. Ali slaps his face in front of the mirror when he is trying to sober his drunken brain while gambling. Finally Fassbinder shoots the hospital ward through a wall mirror. I read the mirrors as the opposite of the jumbled colors and the penetrations. In a mirror the self collects and integrates itself, as in psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s “mirror stage” or perhaps as in Ali’s mirror-phrase, Kif-kif, Who cares? When he says it, Ali goes back into his Arab fatalism, complete unto himself, indifferent to any other.

I also sense in Fassbinder’s colors and shapes contrasts between relationships which are separated and contained and relationships which are close and interpenetrated. Emmi’s apartment is like her dresses, a jumble of colors and shapes. By contrast, the blond’s apartment has a well-defined decor, large clear shapes and clear echoings and contrasts, for example, of her red drapes and her red dress.

All three times Emmi and Ali were dancing in the bar a lurid red light formed around their heads. Red as the intimate and sexual, but there is messy sex (Emmi and Ali) as opposed to distant sex in which the partners are coolly using each other (Ali and the blond).