People read the title Amarcord as “I remember” in the local dialect of Rimini, the town on the Adriatic where Fellini grew up and the let’s-pretend site of this movie (although it was mostly photographed at Cinecittà). Accordingly people think of this movie as autobiographical, as reminiscences of Fellini’s adolescence. But he objects: “I’m always a bit offended when I hear that one of my films is ‘autobiographical’: it seems like a reductionist definition to me, especially if then, as it often happens, ‘autobiographical’ comes to be understood in the sense of anecdotal, like someone who tells old school stories.”

Rather, “Amarcord” for Fellini means “a way of thinking that is doubled, controversial, contradictory, and basically the coexistence of two opposites, the fusion of two extremes, such as detachment and nostalgia, judgment and complicity, refusal and assent, tenderness and irony, weariness and agony. It seemed to me that the film I wanted to make represented all this.”

I think Fellini is right, that his film does present a “doubled” way of thinking, and of course he presents it in his episodic, circus-y style. He gives us a succession of events in one year in the life of this town. To show us the whole town, he uses a big cast, and it helps to know some of them before seeing the picture:

- Titta. The fifteen-year-old hero (Bruno Zanin)

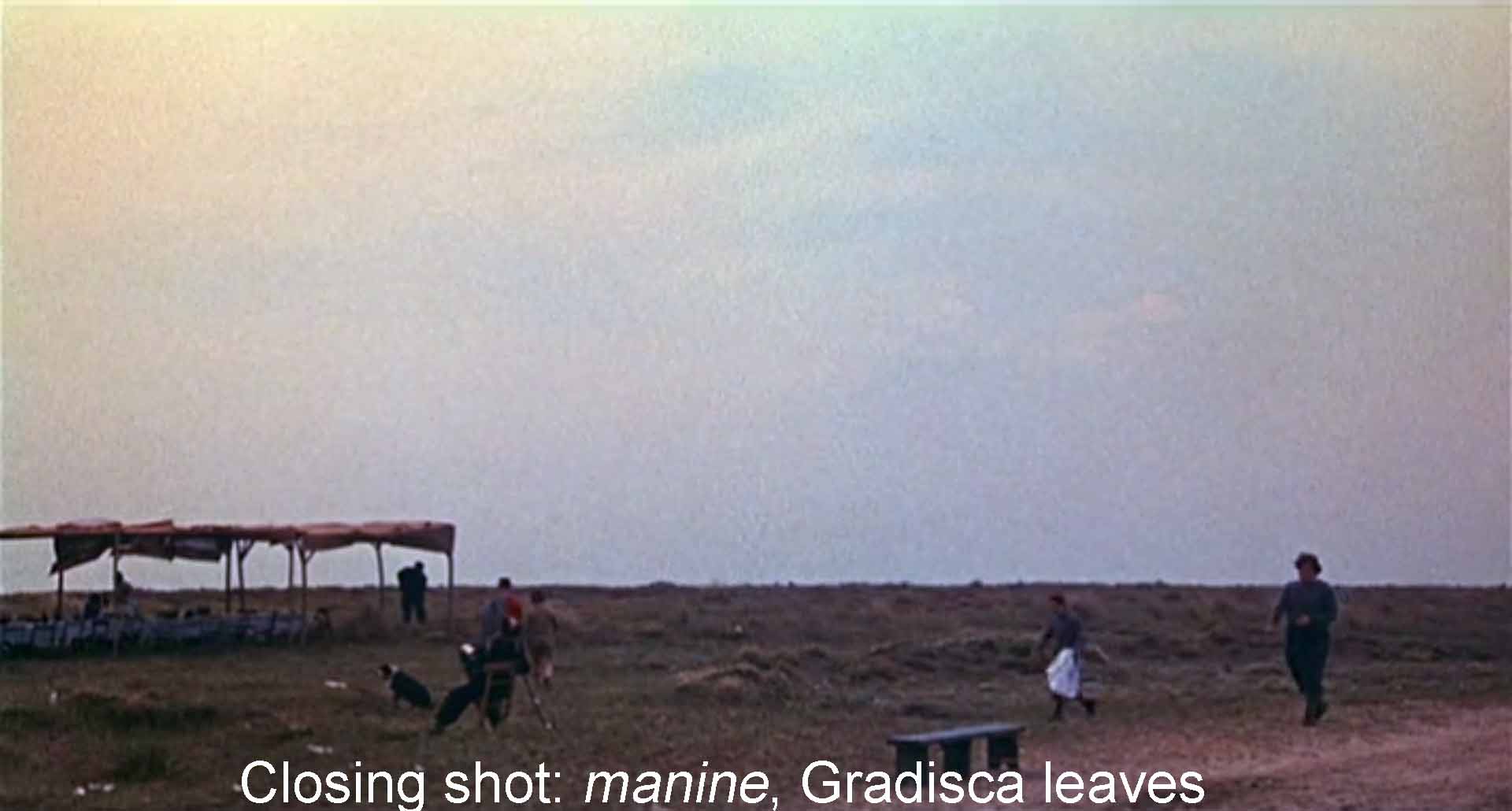

- Gradisca. The town beauty, adored by Titta (Magali Noël).

- Aurelio Biondi. Titta’s father who has an explosive temper (Armando Brancia).

- Miranda Biondi. Titta’s equally furious mother (Pupella Maggio).

- Lallo. Titta’s uncle, a Fascist layabout (Nando Orfei) pampered by his sister, Titta’s mother.

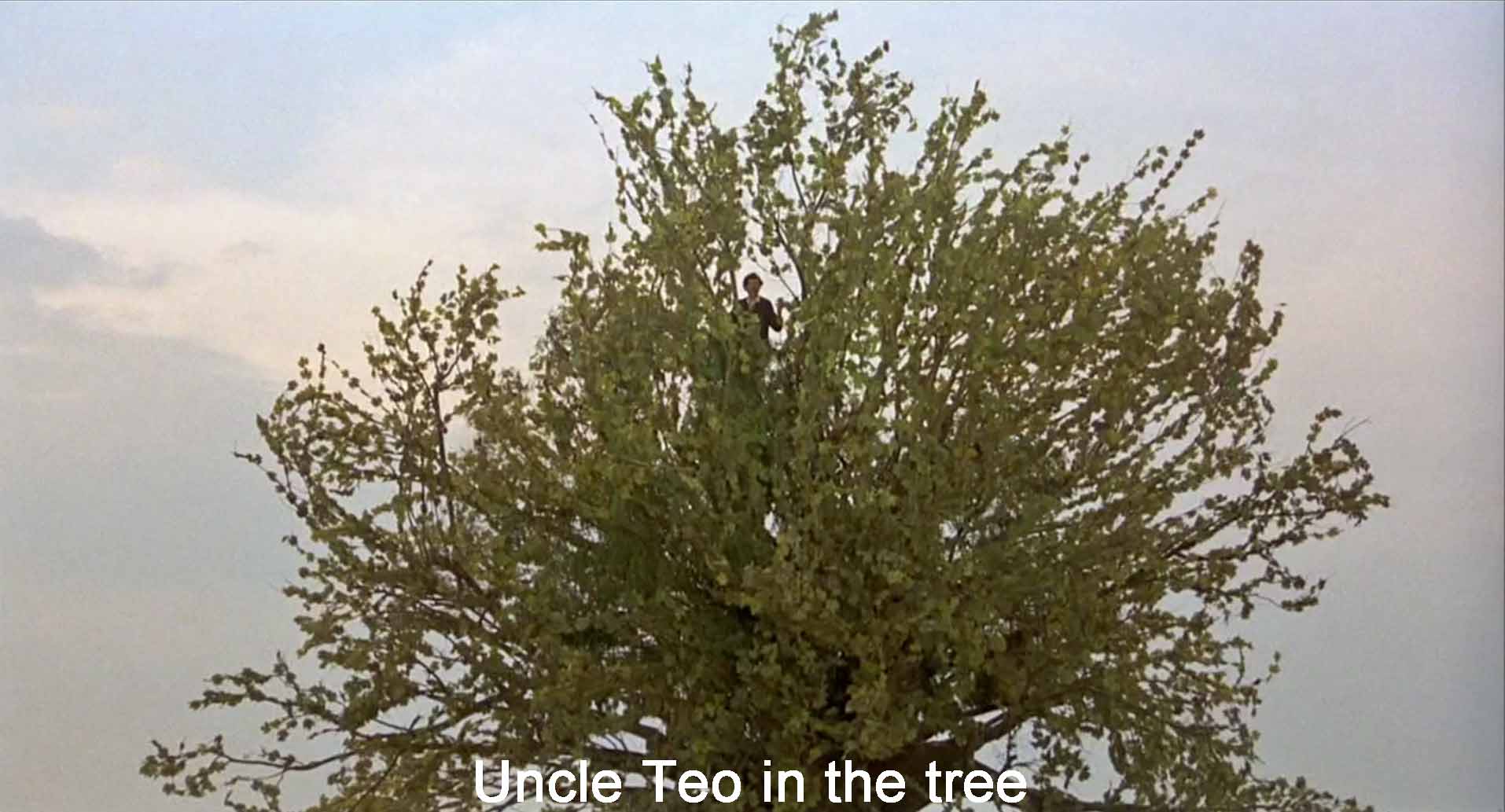

- Teo. Titta’s crazy uncle, Aurelio’s brother, usually in an asylum (Ciccio Ingrassia)

- Volpina. The town nymphomaniac (Josiane Tanzilli)

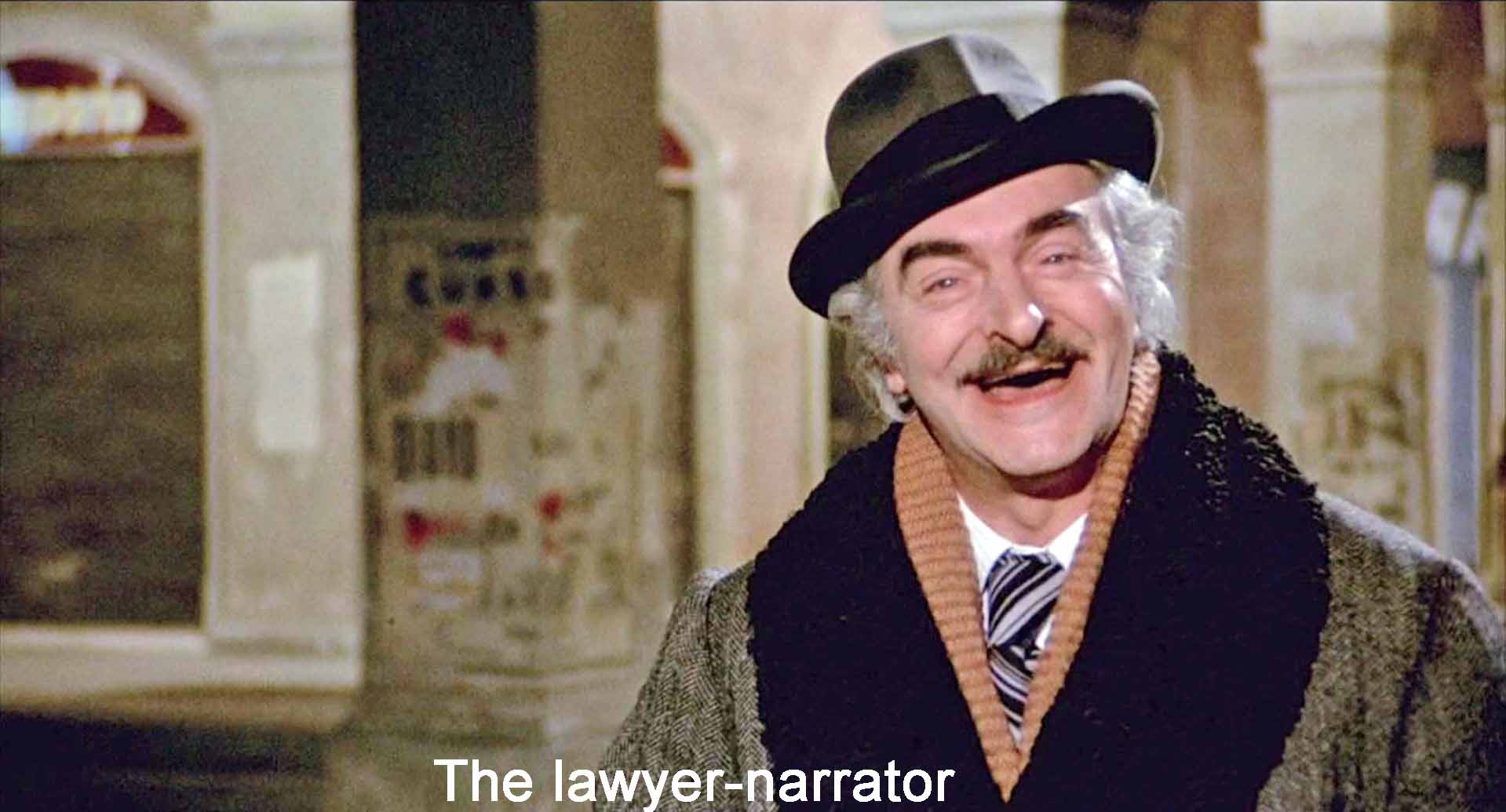

- The lawyer-narrator. One of several characters who speak directly to the camera (Luigi Rossi)

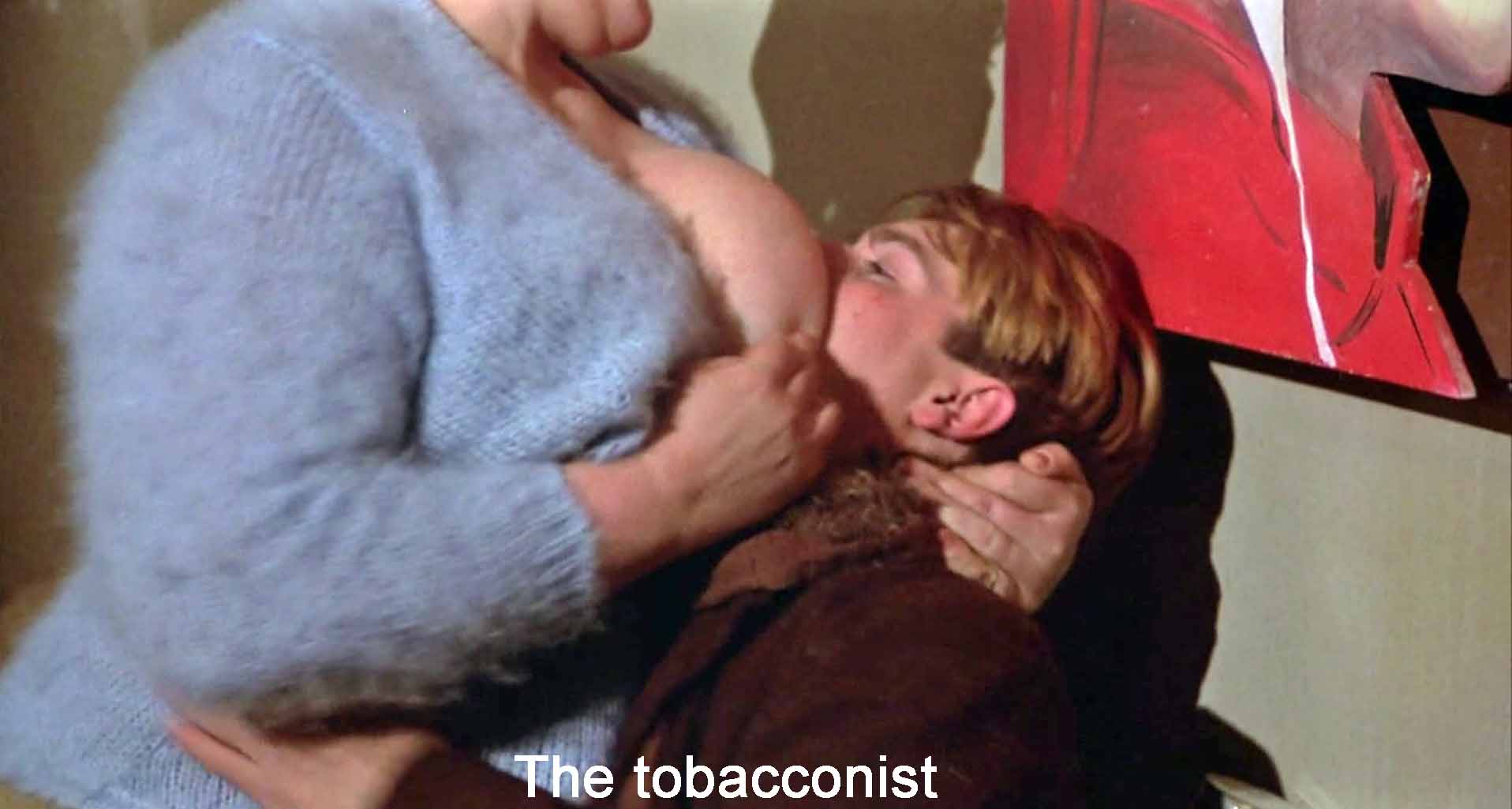

- The tobacconist. Her incredible breasts become Titta’s sexual adventure (Maria Antonietta Beluzzi)

Back to the film: “Another title I wanted to give it was Il borgo in the sense of a medieval enclosure, a lack of information, a lack of contact with the unheard of, the new.” In this vein, one recurring image in Amarcord is fog or smoke, a visual emblem for the superstition and ignorance of the people of Rimini. The Church and the Fascist regime and the dreadful schooling all compound this ignorance.

Adding to the confusion are the nicknames. Nobody goes by their right name. Everybody is addressed by a nickname usually based on some body feature like “Nose” or some obscenity like “Patacca” (= cunt) or some striking incident like “Gradisca” (=“Please do,” based on her night with a visiting prince). The nicknames limit the social circle of the townspeople to the townspeople—an outsider can’t figure out who’s who. Further confusion comes because all the local institutions set out to persuade the kids that Fascist Italy really embodies the glories of ancient Rome, that Fascist Italy is “young and ancient.”

”Young and ancient”—interestingly this was a phrase Fellini used in 8½ to describe the cleansing Muse his hero so desperately sought. Here the words belong to the bosomy professor of mathematics as she ecstatically applauds the regime’s identification with antique Rome. Lallo, one of the vitelloni (=big calves) who have found a berth in the Fascist regime, translates her praise into a testicular obscenity (in the best manner of Silvio Berlusconi or Donald Trump).

More indoctrination and confusion comes from mass culture, especially the movies. In one key scene Titta feels his way up Gradisca’s thigh as they both are watching a movie, Beau Geste (Wellman, 1939). Mass culture—movies, this movie—sets Gradisca to looking for her Gary Cooper (in his Foreign Legion uniform no less). Titta and his buddies sit in an old car masturbating to fantasies about movie actresses. Dance music helps Titta’s uncle Lallo seduce middle-aged tourist ladies. Sex is inflected through pop culture.

Sex. Sex drives this whole film. The opening scene shows the arrival of manine, airborne poplar seeds that mark the beginning of spring. We go on from there to an ancient fertility ritual, the burning of the witch of winter. And then we see the sexy teacher of math, the men admiring the new women coming to the brothel, the priest’s preoccupation with the boys’ masturbating, Titta’s loafer uncle making out with the middle-aged tourist women at the Grand Hotel, Titta’s crazy Uncle Teo high in a tree shouting, “I want a woman.” Then comes one sexless interlude as the townsfolk go out to sea to see the ocean liner Rex. But we come back to sex with Titta and his pals dreamily waltzing as they fantasize about women at the Grand Hotel, Titta’s effort with the hefty tobacconist, then reality with the death of Titta’s mother, and finally the year’s cycle comes to an end with the return of the manine and Gradisca’s marriage to her balding, pot-bellied “Gary Cooper,” a carabiniere, one of the regime’s enforcers. Throughout, we have watched the boys lusting after every female culminating in Titta’s escapade with the big-breasted tobacconist.

As T. Eliot summed up life, “Birth and copulation and death.” Via sex, we have journeyed through fantasy and reality as Fellini develops universality. He systematically takes us through air, fire, earth, and water, with piss and shit thrown in for good measure. More tellingly, Amarcord deals with a human universal, adolescence.

Two things define human adolescence: sexual desire and growth in size. One can hardly miss the theme of sex in Amarcord, but changes in size are all through as well. Fellini began his career as a cartoonist and caricaturist (the word literally means overloaded). The caricaturist exaggerates a facial or bodily characteristic, Obama’s ears or Kim Il Jung’s babyface. In Amarcord Fellini has that kind of fun exaggerating. He gives us big bottoms, big bosoms, and big bombast from the Fascists. Think of the grand Grand Hotel or the gigantic Rex towering ominously over the little boats from town or the huge breasts of the tobacconist or the massive snowfall or the motorcyclist roaring through town with incredible speed.

The least explicit but most startling instance of size is the way Fellini has interpreted a big national political movement through individual psychology, here a perpetual adolescence. Fellini has spoken of the “perpetual adolescence” that led Italians to fall for Mussolini’s fascism. And one might understand the preoccupation with size as referring at some deep level to that part of a man that grows in size in response to sex.

In this connection one striking instance of exaggerated size is the huge liner, the Rex, towering over the small dinghies of the townsfolk. Historically the regime touted Rex as showing fascism’s technical ability on a par with the builders of the Queen Mary, the Bremen, and the Normandie. But Fellini lets us see that this Rex is really a cardboard cut-out floating on a sea of plastic sheeting.

In short, this is a film that looks at adolescence, both real adolescence and the perpetual adolescence of a small town kept childish by the church, the schools, the political regime, and its own foolishness and superstition. Really, then, what Fellini has created is a study of a universal human experience—adolescence, but here it’s adolescence year after year, leading to an understanding of fascism as a kind of comic exaggeration.

Is anyone in this picture really grown up? What is so wonderful about Fellini is the way he can so ridicule these people and even show contempt for them and enlist us in that contempt, and yet at the same time, love them. That is truly amazing. It is what makes people love Fellini and go on loving him years after his death.