Ingmar Bergman, The Seventh Seal (Det Sjunde Inseglet), 1957.

Norman N. Holland

Ways to enjoy: Surely this masterpiece deserves to be seen first without my commentary.

Even if you have seen it before, view it again. When you do, focus on two things.

First, watch for the contrast between the two forms of religion that Berman shows.

Second, be alert to things moving up off the ground (jumping, standing on a stage,

ladders, heights, juggling, and so on).

Aside from giving us a masterpiece, Ingmar Bergman in The Seventh Seal has

created a strange and wonderful paradox: a singularly modern medium treated in a

singularly unmodern style—a medieval film. It is medieval in the trivial sense of

being set in Sweden of the fourteenth century. More importantly, it is a

traditional Dance of Death, a Totentanz or morality play. The whole film moves

towards that ultimate moment when the allegorical figure of Death, robed in black

like a monk, carrying scythe and hourglass, leads the characters away in a dancing

line under the dark, stormy sky. (This legendary shot, strangely, was unplanned.

Bergman seized the moment, pressing crew members into service as the silhouetted

characters.)

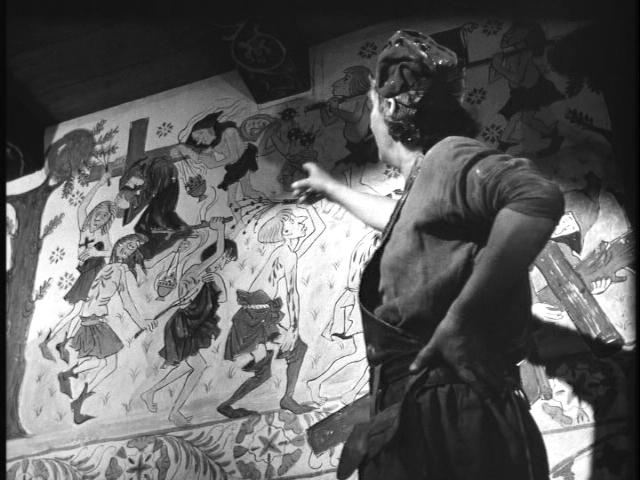

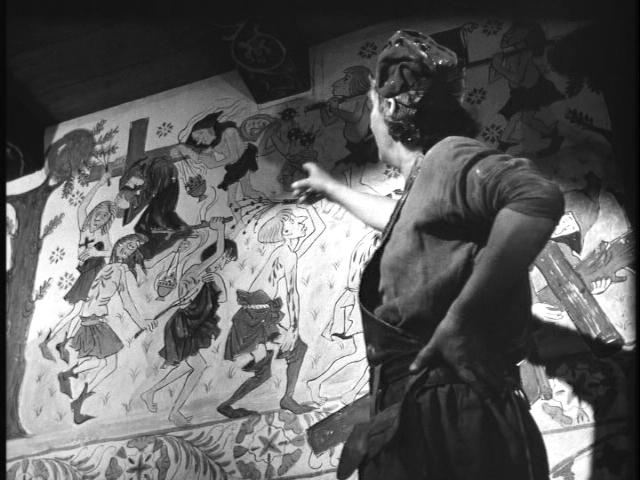

Most important, Bergman shows us, as medieval artists did, what modern critics

call a “figural” reality, which we can understand only by seeing that it

prefigures something beyond itself. “My intention;” Bergman writes in a note to

the film, “has been to paint in the same way as the medieval church painter;” and

lo and behold! he has done just exactly that. Most important, Bergman shows us, as

medieval artists did, an allegorical, iconic reality, in Erich Auerbach's term, a

figural reality which can be understood only by seeing that it figures forth

something beyond itself.

prefigures something beyond itself. “My intention;” Bergman writes in a note to

the film, “has been to paint in the same way as the medieval church painter;” and

lo and behold! he has done just exactly that. Most important, Bergman shows us, as

medieval artists did, an allegorical, iconic reality, in Erich Auerbach's term, a

figural reality which can be understood only by seeing that it figures forth

something beyond itself.

It is hard to imagine more than half a century later the astonishment this film

created when it was released in the U.S. Reviewers for the media confessed they

were baffled (and annoyed) by it. Academic critics like me were amazed and

delighted to find a film that asked such serious questions as, Is there a God?

Why does He allow plagues and death? What is religion? And answered them! For many

of us, it was the first time we had seen such a thing.

The Seventh Seal pictures a Crusader's quest, not in some faraway Holy Land, but

in his own fourteenth-century Sweden. After ten years of holy war, the Crusader,

Antonius Block, has returned home, weary, bitter, and disillusioned. On the shore,

he prays but elicits only the ominous black figure of Death who steps out of a

series of striking dissolves to claim him. The Crusader, however, challenges Death

to a game of chess, and Death agrees. If the knight wins, he escapes Death, and so

long as the game goes on, he is free to continue his quest: to gain certain

knowledge of God and to do one significant act during his lifetime. As Death and

the Crusader play at intervals through the film, the knight moves on a pilgrimage

through Sweden, the land ravaged by the Black Death.

he prays but elicits only the ominous black figure of Death who steps out of a

series of striking dissolves to claim him. The Crusader, however, challenges Death

to a game of chess, and Death agrees. If the knight wins, he escapes Death, and so

long as the game goes on, he is free to continue his quest: to gain certain

knowledge of God and to do one significant act during his lifetime. As Death and

the Crusader play at intervals through the film, the knight moves on a pilgrimage

through Sweden, the land ravaged by the Black Death.

I think Bergman wants us to draw some obvious modern parallels to his medieval

characters. He has written, “Their error is the plague, judgment Day, the star

whose name is Wormwood. Our fear is of another kind but our words are the same.

Our question remains.” Our plague is the threat of atomic annihilation or a war of

religions. We too have our soldiers and priests. In 1956, Bergman called them,

“communism and catholicism, two -isms at the sight of which the pure-hearted

individualist is obliged to put out all his warning flags.” Nowadays, we face the

religious fanaticisms of East and West.

Yet we would be limiting Bergman's achievement to call this film only a realistic

portrayal of the fourteenth century or a parable for the age of the bomb. He is

going beyond a mere Dance of Death. After all, all humans everywhere have always

lived with death. Bergman asks bigger questions. His Crusader asks, If death is

the only certainty, where is God?

The knight's quest gives us the answer, although he himself never seems to learn

it—or to learn that he has learned it. Accompanying this abstract idealist is his

foil: his positivistic, materialistic, hedonistic squire. He doesn't question. He

assures us the only reality is the body. The Crusader, however, wants more. He

wants certainty about God, for “to believe without knowledge is to love someone in

the dark who never answers.”

The Crusader and his squire acquire followers. The squire rescues a mute woman

from rape by Raval (Bertil Anderberg), a seminarist, that is, a lower-order of

cleric, who is now a thief, robbing corpses. It was he who had urged them to go on

the Crusade in the first place. The Crusader and his squire see a trio of actors

put on a bawdy skit which is interrupted by a procession of flagellants and by a

smith's wife's running off with one of the actors. The Crusader meets Jof and Mia,

actors, and their baby Michael (the squire having earlier saved Jof from being

tormented by the seminarist in the tavern). The cuckolded smith now joins the

knight, the squire, and the actors on their journey. They also pick up the smith's

wife (whose actor has feigned death only to be cut down by the real Death). As

they ride through the dark and terrifying woods, they see a witch about to be

burned. The Crusader resumes his game with Death and, by distracting him, allows

Jof, Mia, and the baby to escape. Knight, squire, smith, smith's wife, squire,

squire's woman—all climb up to the castle where the knight's wife, Karin, serves

them a meal. Then Death comes, the silent woman speaks, and the grim reaper

gathers them in. In the distance, Jof, who can see visions, sees the other

characters in that final Dance of Death against the horizon.

The Crusader's quest is ended, and he has achieved his one significant action:

rescuing Jof, Mia, and the baby. Yet what the Crusader found at first was an

altogether different kind of humanity: people who believe only in God as a

scourge, the cause of plagues and death, and who punish in their turn.

Religion for them becomes suppression, cruelty, persecution, the burning of

innocent girls as witches, the gruesome realism of the crucifixes in the peasants'

churches. In one of the grimmest scenes on film, Bergman shows us a procession of

flagellants: a line of half-naked men lashing one another; monks struggling under

the weight of huge crosses or with aching arms holding skulls over their bowed

heads; the faces of children who wear crowns of thorns; people walking barefoot or

hobbling on their knees; a great gaunt woman whose countenance is sheer blankness;

slow tears falling down the cheeks of a lovely young girl who smiles in her

ecstasy of masochism. The whole thing echoes the church painter's repulsive

murals. The procession interrupts the jolly, bawdy “art” of a trio of strolling

players and halts while a mad priest screams abuse, shouting out the ugliness and

mortality of his audience, long nose or fat body or goat's face. Glutted with

hate, he joyfully proclaims the wrath of God, and the procession resumes its

dogged way over the parched, lifeless soil.

Religion for them becomes suppression, cruelty, persecution, the burning of

innocent girls as witches, the gruesome realism of the crucifixes in the peasants'

churches. In one of the grimmest scenes on film, Bergman shows us a procession of

flagellants: a line of half-naked men lashing one another; monks struggling under

the weight of huge crosses or with aching arms holding skulls over their bowed

heads; the faces of children who wear crowns of thorns; people walking barefoot or

hobbling on their knees; a great gaunt woman whose countenance is sheer blankness;

slow tears falling down the cheeks of a lovely young girl who smiles in her

ecstasy of masochism. The whole thing echoes the church painter's repulsive

murals. The procession interrupts the jolly, bawdy “art” of a trio of strolling

players and halts while a mad priest screams abuse, shouting out the ugliness and

mortality of his audience, long nose or fat body or goat's face. Glutted with

hate, he joyfully proclaims the wrath of God, and the procession resumes its

dogged way over the parched, lifeless soil.

Such is religion, Bergman seems to say, to those who see God as hater of life.

Art (as represented by a surly, tippling church painter) becomes the

representation of death, both physically and allegorically, to gratify the

people's lust for fear. The painter assures us, “I paint life as it is.” Living,

as shown in a grotesque scene in an inn, becomes a sardonic, “Eat, drink, and be

merry.” Cinematically, Bergman identifies this side of the ledger by great areas

of blackness in the film frame and often by slow, somber dissolves form shot to

shot. Musically, the sound track treats even scenes of merrymaking with the Dies

Irae theme. In his notes to the film, Bergman tells how,

As a child I as sometimes allowed to

accompany my father when he traveled about to preach in the small country churches

. . . . While Father preached away . . . . I devoted my interest to the church's

mysterious world of low arches, thick walls, the smell of eternity, . . . the

strangest vegetation of medieval paintings and carved figures on ceiling and

walls. There was everything that one's imagination could desire: angels, saints

. . . frightening animals . . . All this was surrounded by a heavenly, earthly, and

subterranean landscape of a strange yet familiar beauty. In a wood sat Death,

playing chess with the Crusader. Clutching the branch of a tree was a naked man

with staring eyes, while down below stood Death, sawing away to his heart's

content. Across gentle hills Death led the final dance toward the dark lands.

But in the other arch the Holy Virgin was walking in a rose garden, supporting the

Child's faltering steps, and her hands were those of a peasant woman . . . . I

defended myself against the dimly sensed drama that was enacted in the crucifixion

picture in the chancel. My mind was stunned by the extreme cruelty and the extreme

suffering.

The Seventh Seal finds another God for us—or at least another certainty than

death—not in the wormwood-and-gall institutional religion of suffering and

crucifixion, but in the simple life of the strolling actor and juggler named Jof

(Joseph), his girl-wife Mia (Mary), and their baby. As if to make the low parallel

to the Holy Family even more clear, Jof plays the cuckold in the troupe's little

Pierrot-Columbine skit.

Jof is also the artist. He is given to visions, and Bergman shows us one, “of

the Holy Virgin . . . supporting the Christ child's faltering steps.” Except for

the Crusader, Jof is the only one who can see the allegorical figure of Death. To

the Crusader's materialistic squire, for example, Death appears not as an iconic

figure but as a grisly, rotting corpse. Jof is a maker of songs whose simple

melodies provide the sound track for this, the credit side of the religious

ledger. Cinematically, Bergman gives us the holiness of life represented by Jof's

family in light, airy frames; quick cuts tend to replace the slow dissolves used

for the religion of death.

Yet even innocent Jof can be converted to a thief and a buffoon by the

death-forces. In the grotesque comic scene at the inn, he is tormented with

flames, forced to jump up and down on the board table in an exhausting imitation

of a bear, parodying his own acrobatic ability to leap beyond the ordinary human.

An artist stifled in his art, he responds by becoming a rogue: he steals the

bracelet that Raval had taken from a corpse as he makes his getaway.

This grim reductio ad absurdum proves, as it were, that death and the religion

of death cannot be the only certainty.  As the mad young girl about to be burned

for a witch tells the Crusader, you find God (or the Devil who implies God) in the

eyes of another human being. But the abstractly questioning Crusader says he sees

only terror in her eyes.

As the mad young girl about to be burned

for a witch tells the Crusader, you find God (or the Devil who implies God) in the

eyes of another human being. But the abstractly questioning Crusader says he sees

only terror in her eyes.

He seems for a moment to find his certainty of God in a meal of wild

strawberries and milk handed him by the gentle Mia, in effect, a holy communion of

life as opposed to the bread and wine consecrated to Death.

Medieval herbals interpreted plants allegorically, as having religious meaning.

Because the strawberry has its seeds on the outside, it can serve as an emblem of

perfect righteousness, and strawberries were associated with the Virgin. They were

“fruits of the spirit.” A psychoanalytic critic, however, might point to the milk

and berries as symbols for the nipple and its nurturing fluid. Bergman tends to

identify them in his films with a mammary or sexual life-force, as here.

Also, in doing his “one significant act,” the Crusader has performed the

service of the knight traditional in medieval art, not the colonizing of the Holy

Land but the protecting of the Holy Family. He leads Joseph, Mary, and the Child

away from the plague but through the Dark Forest. As the knight plays chess with

Death, he sees that the visionary Jof has recognized the Black One, intuited his

family's danger, and is trying to escape. To help him, the knight busies Death by

knocking over the chessmen, incidentally giving Death at least the chance to cheat

and win. In losing the game, the knight gives up his own life to let Jof and Mia

escape (in a tumultuous, stormy scene like paintings of the Flight into Egypt).

And yet, although the Crusader has pointed the way for us in the audience, he

seems not to have found it for himself. He persists in his quest for abstract

answers. He leads the rest of his now doomed band, the smith, the smith's

lecherous wife, the squire, and the squire's silent woman up from the seashore to

his castle. There, in a curiously emotionless scene, the Crusader distantly greets

his wife whom he has not seen for ten years. He admits his disillusionment but

tells her he is not sorry he went on his quest. With the chess game lost and death

near, he knows it is too late for him now to act out the importance of the family

himself, but he has learned its worth, although he does not realize its full godly

significance. As his wife reads the lurid images of Revelation viii: “And when he

had opened the seventh seal,” Death, whom they all seem to await, appears. The

Crusader asks once more that God prove himself. The silent woman opens her mouth

(the seventh seal?) and speaks, “It is finished,” the sixth of the seven last

words from the Cross. Death gathers them all in his cloak, filling the screen with

black. The mute girl's ecstatic face dissolves into Mia's as she huddles with Jof

and the baby.

In short, then, the film answers its question, If Death is the only certainty,

where is God?, by saying, You find God in life. The opening shots of the film set

up the contrast: first, a lowering, empty sky; then the same sky but with a single

bird hovering against the wind. Life takes meaning from its opposition to death,

just as Jof and Mia's simple love of life takes meaning from the love of death

around them—or as a chess game takes form in a series of oppositions.

Bergman made the chess game one of the central images of the film. It dictates

much incidental imagery such as the knight's castle or the “eight brave men” who

burn the witch. The playing (spela) of chess matches the playing (spela) of the

strolling trio of actors. Both are traditional images for the transitoriness of

life (juxtaposed, for example in Don Quixote, chapter 12 of Book II). All the

world's a stage, life is a play, and Death robs us of our roles. Life is a game;

Death jumbles—and humbles—the chessmen all together back in the box.

There are also some particular correspondences (somewhat confused for an

English-speaking audience by the Swedish names for the chessmen). The Crusader,

distinguished by his cross, is the king of the chess game: when he is lost, all

the rest are lost, too. It is not the knight but the juggler Jof who is the chess

knight (in Swedish, springare, the “leaper”). Only the king and the knight can

rise above the chess board, and in the film only these two men have visions that

go beyond reality. The juggler (chess knight) can at all times jump out of the

two dimensions of the board. Jof's powers as a seer are almost exactly parodied by

his tormentors' forcing him to jump up and down on the board table in the

grotesque scene at the inn. The only other chess man who can rise off the board

during the game is the king, and then only when he is castling—going home, like

this Crusader. All the pieces or characters, of course, in their own moment of

death, when they are taken from the board, can see beyond it.

Bergman's allegory is simple. Up means vision into a “higher” reality. The

witch, lifted up (on a ladder!) to be burned sees Death and emptiness. In effect,

she is cured from her satanic illusions into atheism. Skat, the lecherous actor,

when he climbs a tree, can then see Death. (In a wonderful moment, after Death has

sawed through Skat's tree, a squirrel jumps up on the stump—life goes on.)

These visions beyond the physical reality of the board, however, like the

Crusader-king's, are limited to the allegorical figure of Death. The

juggler-knight, the “leaper” (in Kierkegaard's “leap” of faith?) can see not only

Death, but also the holy life of the Mother and Child.

In other words, it is the artist who has the vision the Crusader seeks in

abstract answers to abstract questions. Even the church painter, although

committed to the world of the death-religion and to painting “life as it is,”

stands above things, on a scaffold. He is able to prefigure the events of the film

in the scenes he paints of a man dying in torment, of Death sawing down a tree

where a man has tried to hide, or of the Dance of Death which is the next-to-last

shot of the film.

Jof, however, is a greater kind of artist. He says his visions give “not the

reality you see, but another kind.” He hopes his Christ-like infant will grow up

to achieve what he calls “the impossible trick,” keeping the juggled ball always

in the air, above the board, as it were, in the realm of the supernatural.

Bergman himself is this kind of artist: he has called himself “a conjurer” working

with a “deception of the human eye” that makes still pictures into moving

pictures.

In The Seventh Seal, as in any great work of art, theme and medium have become

one. Bergman depicts the real world objectively, with tenderness and joy, also

anger, but he shows us a world in which reality signifies something beyond itself.

He lifts his film out of mere physical realism and makes his audience of chessmen

with tricked eyes see in their own moves something beyond the board. “My

intention,” Bergman wrote in a note to the film, “has been to paint in the same

way as the medieval church painter,” and lo and behold! we can see him doing just

exactly that.

Ways to enjoy: I’ve mentioned two already: paying attention to the two kinds of religion; watching for characters moving vertically off the ground. There are others. For example, be alert to the differences between the beautiful or handsome faces and the opposite, the uglies, and where they occur.

Ways to enjoy: One of the great charms of this film is its very realistic portrayal of medieval life and art, particularly in the desperate time of Black Plague. While Bergman’s dates are a couple of centuries off, his medievalism isn’t. Enjoy it.

Ways to enjoy: Notice the very gray gray scale in this film. There are some pure whites (the Knight’s hair, and some pure blacks (associated with Death), but most of the film is in gray. Appreciate that gray scale and the extraordinary desolation of the landscape. It all makes for the seriousness of this film.

prefigures something beyond itself. “My intention;” Bergman writes in a note to

the film, “has been to paint in the same way as the medieval church painter;” and

lo and behold! he has done just exactly that. Most important, Bergman shows us, as

medieval artists did, an allegorical, iconic reality, in Erich Auerbach's term, a

figural reality which can be understood only by seeing that it figures forth

something beyond itself.

prefigures something beyond itself. “My intention;” Bergman writes in a note to

the film, “has been to paint in the same way as the medieval church painter;” and

lo and behold! he has done just exactly that. Most important, Bergman shows us, as

medieval artists did, an allegorical, iconic reality, in Erich Auerbach's term, a

figural reality which can be understood only by seeing that it figures forth

something beyond itself. he prays but elicits only the ominous black figure of Death who steps out of a

series of striking dissolves to claim him. The Crusader, however, challenges Death

to a game of chess, and Death agrees. If the knight wins, he escapes Death, and so

long as the game goes on, he is free to continue his quest: to gain certain

knowledge of God and to do one significant act during his lifetime. As Death and

the Crusader play at intervals through the film, the knight moves on a pilgrimage

through Sweden, the land ravaged by the Black Death.

he prays but elicits only the ominous black figure of Death who steps out of a

series of striking dissolves to claim him. The Crusader, however, challenges Death

to a game of chess, and Death agrees. If the knight wins, he escapes Death, and so

long as the game goes on, he is free to continue his quest: to gain certain

knowledge of God and to do one significant act during his lifetime. As Death and

the Crusader play at intervals through the film, the knight moves on a pilgrimage

through Sweden, the land ravaged by the Black Death. Religion for them becomes suppression, cruelty, persecution, the burning of

innocent girls as witches, the gruesome realism of the crucifixes in the peasants'

churches. In one of the grimmest scenes on film, Bergman shows us a procession of

flagellants: a line of half-naked men lashing one another; monks struggling under

the weight of huge crosses or with aching arms holding skulls over their bowed

heads; the faces of children who wear crowns of thorns; people walking barefoot or

hobbling on their knees; a great gaunt woman whose countenance is sheer blankness;

slow tears falling down the cheeks of a lovely young girl who smiles in her

ecstasy of masochism. The whole thing echoes the church painter's repulsive

murals. The procession interrupts the jolly, bawdy “art” of a trio of strolling

players and halts while a mad priest screams abuse, shouting out the ugliness and

mortality of his audience, long nose or fat body or goat's face. Glutted with

hate, he joyfully proclaims the wrath of God, and the procession resumes its

dogged way over the parched, lifeless soil.

Religion for them becomes suppression, cruelty, persecution, the burning of

innocent girls as witches, the gruesome realism of the crucifixes in the peasants'

churches. In one of the grimmest scenes on film, Bergman shows us a procession of

flagellants: a line of half-naked men lashing one another; monks struggling under

the weight of huge crosses or with aching arms holding skulls over their bowed

heads; the faces of children who wear crowns of thorns; people walking barefoot or

hobbling on their knees; a great gaunt woman whose countenance is sheer blankness;

slow tears falling down the cheeks of a lovely young girl who smiles in her

ecstasy of masochism. The whole thing echoes the church painter's repulsive

murals. The procession interrupts the jolly, bawdy “art” of a trio of strolling

players and halts while a mad priest screams abuse, shouting out the ugliness and

mortality of his audience, long nose or fat body or goat's face. Glutted with

hate, he joyfully proclaims the wrath of God, and the procession resumes its

dogged way over the parched, lifeless soil. As the mad young girl about to be burned

for a witch tells the Crusader, you find God (or the Devil who implies God) in the

eyes of another human being. But the abstractly questioning Crusader says he sees

only terror in her eyes.

As the mad young girl about to be burned

for a witch tells the Crusader, you find God (or the Devil who implies God) in the

eyes of another human being. But the abstractly questioning Crusader says he sees

only terror in her eyes.