Enjoying: This is as complicated a movie as I know. As with Jonze's earlier feature, Being John Malkovich, you'll be tempted to try to figure it out as you go. If you haven't seen it before, I suggest that you resist the impulse. Just watch the movie. But do watch for a turning point, where suddenly the movie stops being some complicated metafilmic thing. The voiceovers stop. The flashbacks (and flashbacks within flashbacks!) stop. The movie relaxes into a simple, straightforward, old-fashioned thriller. Adaptation in at least four senses succeeds.

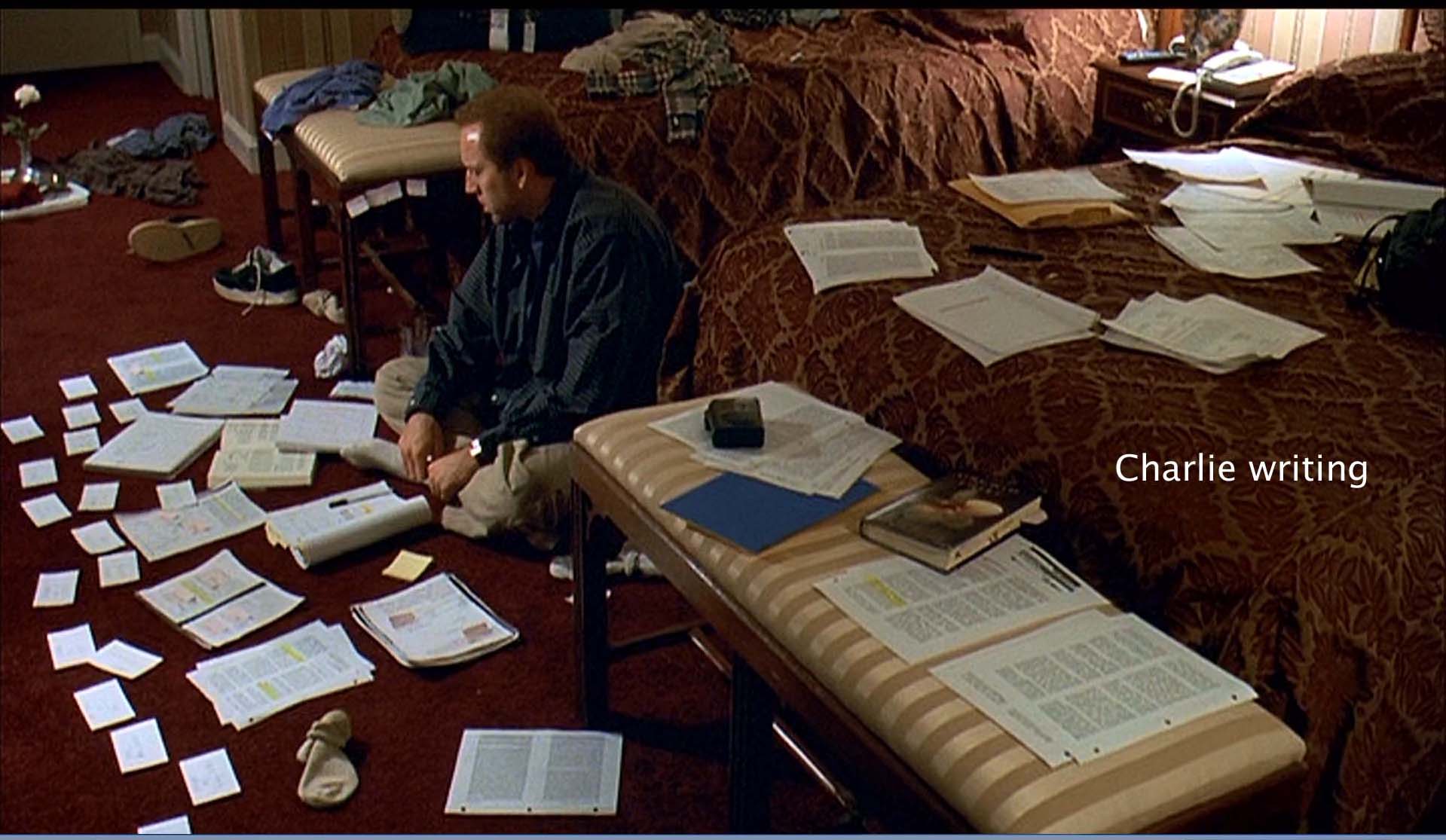

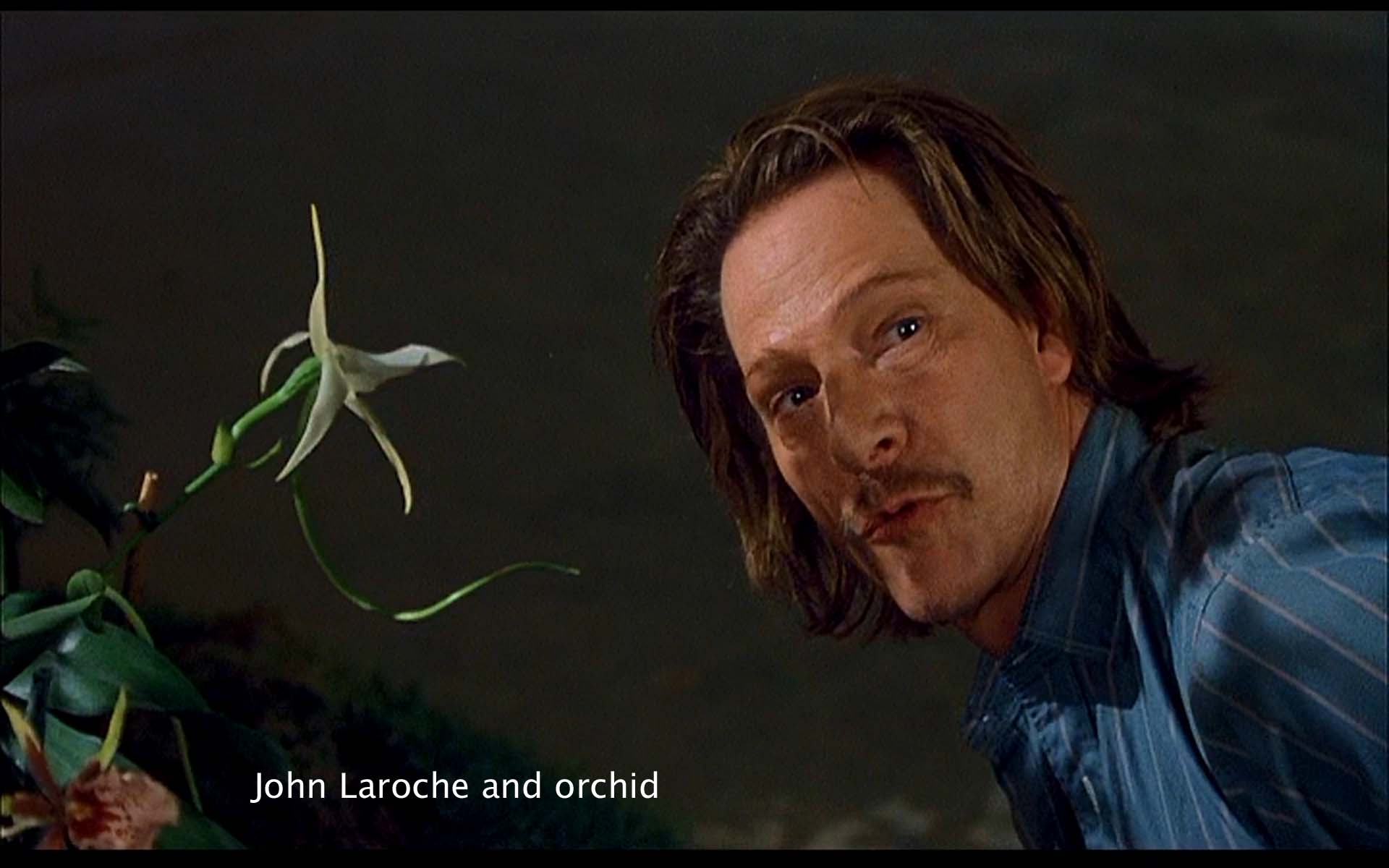

The movie begins with screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (Nicolas Cage) trying to adapt a non-fiction book about orchid thieving by Susan Orlean (Meryl Streep) into a movie and trying, fitfully, to establish a relationship with his girlfriend Amelia. Meanwhile Charlie's devil-may-care brother Donald (also played by Cage) succeeds fabulously in sex and in writing a moneymaking screenplay. Cross-cut with Charlie's flailings are Susan's trips to Florida and her meetings with John Laroche (Chris Cooper), the orchid thief and her own search for the "Ghost Orchid," ever so faintly suggestive of a female body with legs spread. All this she does, while Laroche delivers long monologues on botany, sexuality, evolution, his philosophy, and so on.

The turning point in the movie comes when Charlie allows Donald in, so to speak. In the first part of the movie, Charlie has nothing but contempt for Donald's screenwriting efforts. When his own agent, Marty (Ron Livingstone) tells him he thinks Donald's script is "amazing," Charlie is dumbfounded. He no longer resists. He attends the screenwriting seminar given by Robert McKee (Brian Cox) that he had so contemptuously dismissed when Donald recommended it. There he gets McKee's advice to salvage his efforts (which we have been viewing! for how many minutes?) by putting on a jazzy ending. "Wow them in the end, and you've got a hit. Find an ending."

Acordingly, Charlie brings Donald to New York and has Donald read his tortured script. Donald says they have to meet and investigate Susan Orlean. He springs into action. He meets her and reads her correctly (Charlie having only been able to have sexual fantasies about her). "She's lying." Donald spies on her and finds her continuing relationship with Laroche. He now is developing a porn site on the Internet that includes Susan Orlean, New York sophisticate and staff writer on what is reputedly the best magazine in English, The New Yorker.

On Donald's insistence, the twins travel to Florida, and from there Charlie's metaphysical mess becomes a fairly straightforward thriller, complete with Florida gator (a deus ex machina, such as McKee had warned against, or more properly alligator mississippiensis ex machina). No more voiceovers and flashbacks. Just suspense, gunshots, a car crash, and the boy-gets-girl finale. "This is good," and Charlie concludes the picture and his screenwriting in voiceover—to hell with what McKee says. And to hell with his own wishes: the movie has all the things he said at the beginning he didn't want: drug running, chases, guns . . . It is, as he says, "plot-driven."

Before this turnabout, Susan offers a game-changing insight. Charlie reads from her book: "There are too many ideas and things and people, too many directions to go . . . . the reason it matters to care passionately about something is that it whittles the world down to a more manageable size." "So true," sighs Charlie." What Charlie cares passionately about is finishing his screenplay, and he is willing to subordinate himself to Donald, to whittle himself down, to gain that end. Desiring something passionately makes the world "manageable, you can compromise (adapt) to get it, and Charlie can finish his script.

But this whittling down his "movie about flowers" is not necessarily a good thing. When Susan turns to sex and drugs with Laroche, this intelligent, capable woman in a drug-induced stupor finds a monotonous dial tone "amazing." She wishes she were an ant, she allows a picture of herself on his porn site, and, when she is finally trapped, she says, "I did everything wrong. I want my life back. I want it back before it all got fucked up. I want to be a baby again. I want to be all new."

It's always a good idea to pay close attention to the opening and closing shots. Here the closing shot is clear enough. Simple flowers wax and wane in the midst of modern life; they are seen against speeding car traffic. They have adapted. But there is more: after the closing credits, there is an excerpt from Donald's screenplay for The Three: "We're all one thing . . . . That's what I've come to realize. Like cells in a body. 'Cept we can't see the body. The way fish can't see the ocean." The three characters in Donald's crazy screenplay are one person, and so are Charlie and Donald one person. The film ends with a final metafilmic touch: "In loving memory of Donald Kaufman." To top the joke, in 2003, both Charlie and Donald were nominated for the Oscar for best screenplay based on an "adaptation" of previously published material.

This is a meta-film. That is, it is a film in which its own substance as a film, the physical film that we are watching, becomes part of the film. The first part of the film shows us (in voiceover, later tabooed by McKee) Charlie struggling to write the screenplay. "Do I have an original thought in my head?" is the first line. But this is Charlie working up the screenplay for the movie which we are in fact watching. No wonder Charlie mentions the ouroboros, the snake devouring its own tail. "I'm ouroboros. I've written myself into my screenplay. It's pathetic." The ouroboros is a metaphor for Adaptation itself: this is a film that feeds on itself. As you can imagine this meta- ness has caused much excited fluttering of the critical mind (me included). The Times critic, A. O. Scott, wrote, this is "a movie about its own nonexistence." This kind of thing delights critics, because it produces an uncanny effect.

The film becomes meta- with its opening shot, which is not a shot at all. We view a black screen and hear Charlie's despairing voice as he lists all the things he thinks others think about him: "I'm bald." "I've got a fat ass." (Later, the screenwriting teacher Robert McKee will shout, "God help you if you use voiceover in your work, my friends . . . It's flaccid, sloppy writing." But Charlie uses it all the time.)

The second sequence takes us onto the set of Being John Malkovich and what is perhaps that film's most inventive shot. We see the filming of what John Malkovich sees when he goes through the "portal" into his own mind. He sees everything, every person, every spoken word, even every written word, as "Malkovich." But in the context of this film, what we are seeing is the contents of Malkovich's mind being brought onto the screen, exactly what Charlie Kaufman cannot do in this film. (As the writer of Being John Malkovich, of course, he was highly successful at doing just that.)

The next sequence is Charlie's lunch with Valerie, the studio executive (Tilda Swinton). Even though she tells him he is a genius, he sweats with anxiety as he tells her what he wants to do to adapt Susan Orlean's book. He wants to make a movie about flowers with none of the usual Hollywood stuff of guns and drugs and car chases. Yet this is exactly what he settles for when, finally acknowledging what he passionately cares about, he accepts his world's being whittled down (and he achieves success!).

In short, the whole movement of the movie is to get Charlie to adapt: to write his screen play and to get his romance going with Amelia.

In the last analysis, then, this is a movie about expressing, getting the thoughts out of your head into actions or onto pages. It's a movie about combining, combining Charlie and Amelia and combining Charlie's thoughts into a completed movie. Or we could speak of mating as Laroche might. Or we could use the word the film uses, adaptation.

It has four senses in this movie, count 'em, four. One, Charlie is to "adapt" Susan Orlean's book into a screenplay. Two, adaptation has a very large evolutionary sense: it includes Charlie's imaginings of a film that has in it "all human history," billions of years, or LaRoche's monologues about evolution. Adaptation, he says, is "a profound process." Adaptation is what natural selection selects; it is what makes life itself evolve. Three, you need to adapt to the thing you are to mate with, something Charlie has a lot of trouble doing. Laroche describes it in his very sexy description of how each flower is adapted to the "lovemaking" of the insect that will pollinate it, and how each insect is adapted to its flower. The flower with a 12-inch nectary is pollinated by an insect with a 12-inch proboscis. Their lovemaking makes "something large and magnificent." And four, Charlie has to adapt to what Valerie, the studio exec, and Marty, his agent, want. He has to adapt to Hollywood (as Donald so easily does).

Adaptation is a key word in this movie. Another key word is "amazing." When you hear it you should remember that it now means astonishing, but it used to mean perplexing or baffling—hardly inappropriate for this movie. Keep both meanings in mind. Laroche promises to give the Seminoles something "amazing," but that turns out to be thievery and a drug-growing business. Charlie tells his agent that he wants to show people how "amazing" flowers are. Says insensitive Marty, "Are they amazing?" But he thinks Donald's crazy script is "just amazing. He's goddamn amazing at structure." Susan, stoned, thinks a dial tone is "amazing." And in her final conversation with Charlie, Amelia describes the puppetry in Prague (another smallness) as "amazing." At the end of this movie, as at the beginning, we get a reference back to Jonze and Kaufman's previous movie, Being John Malkovich. As in Amelia's image, "amazing" ceases to be amazing. It becomes part of the whittled-down world. Instead of being really amazed, we adapt.

That is a bitter theme, hard and sour. Is it true for you? You'll have to speak for yourself.

In a very intelligent essay about Adaptation, Lucas Hildebrand writes, "The primary relationships in the film are not between people but between people and their fantasies, and between writers and their own texts." This movie goes into the protagonist's mind and puts its contents on the screen. Often they turn out to be pure fantasy. (Hence, Charlie's acts of masturbation—another kind of "whittling down.") Really, all three of the Jonze/Kaufman movies, their total oeuvre (as of 2010), develop that tactic (as do many of Jonze's music videos and especially the neat Adidas ad he did with Karen O.) We begin with some kind of discomfort or pain, we go into the sufferer's mind, and from there we fly out into fantasy. And isn't that what we do when we go to the movies? And isn't that a kind of whittling down, settling for illusion, something less than real satisfaction? Isn't that adaptation?