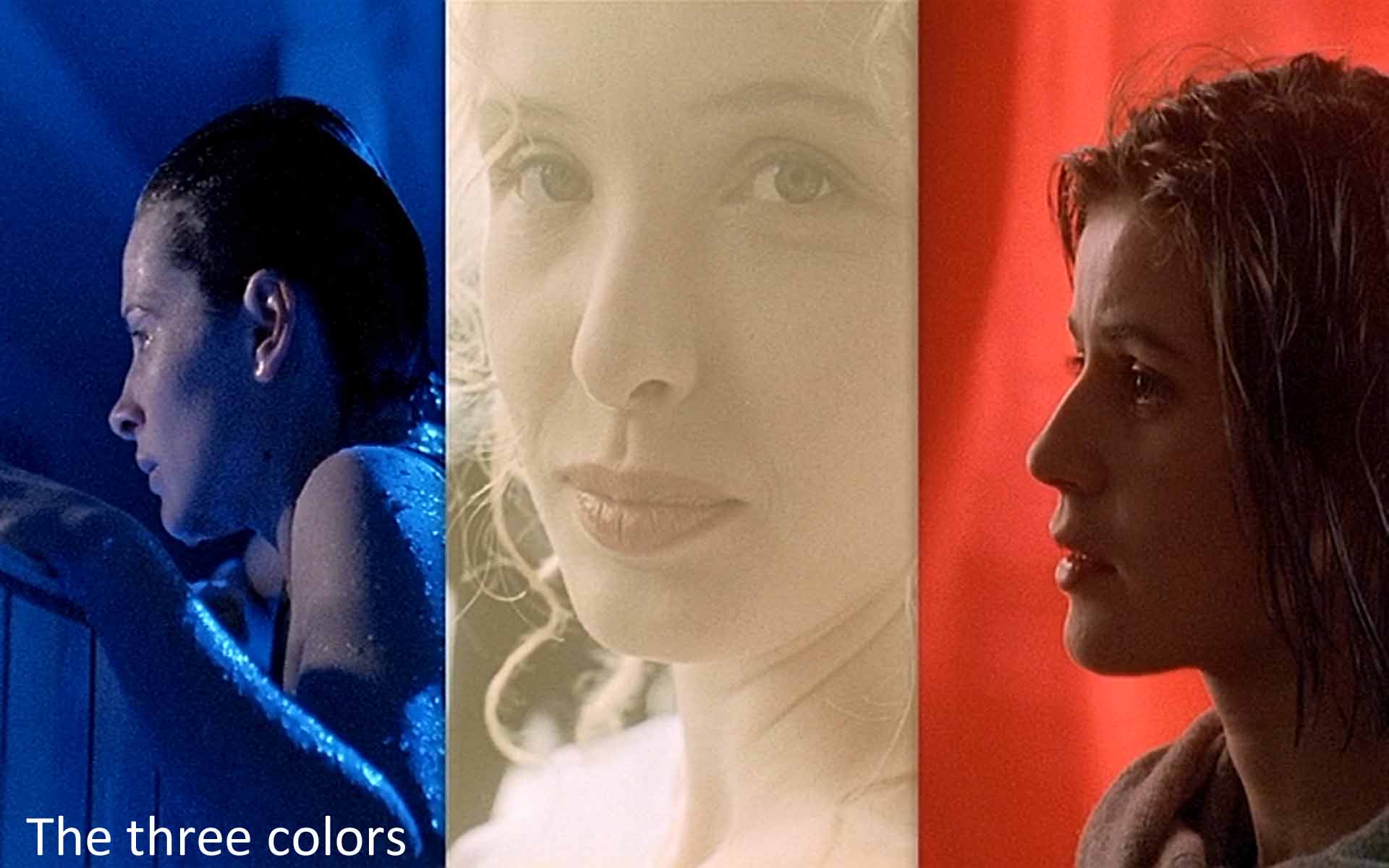

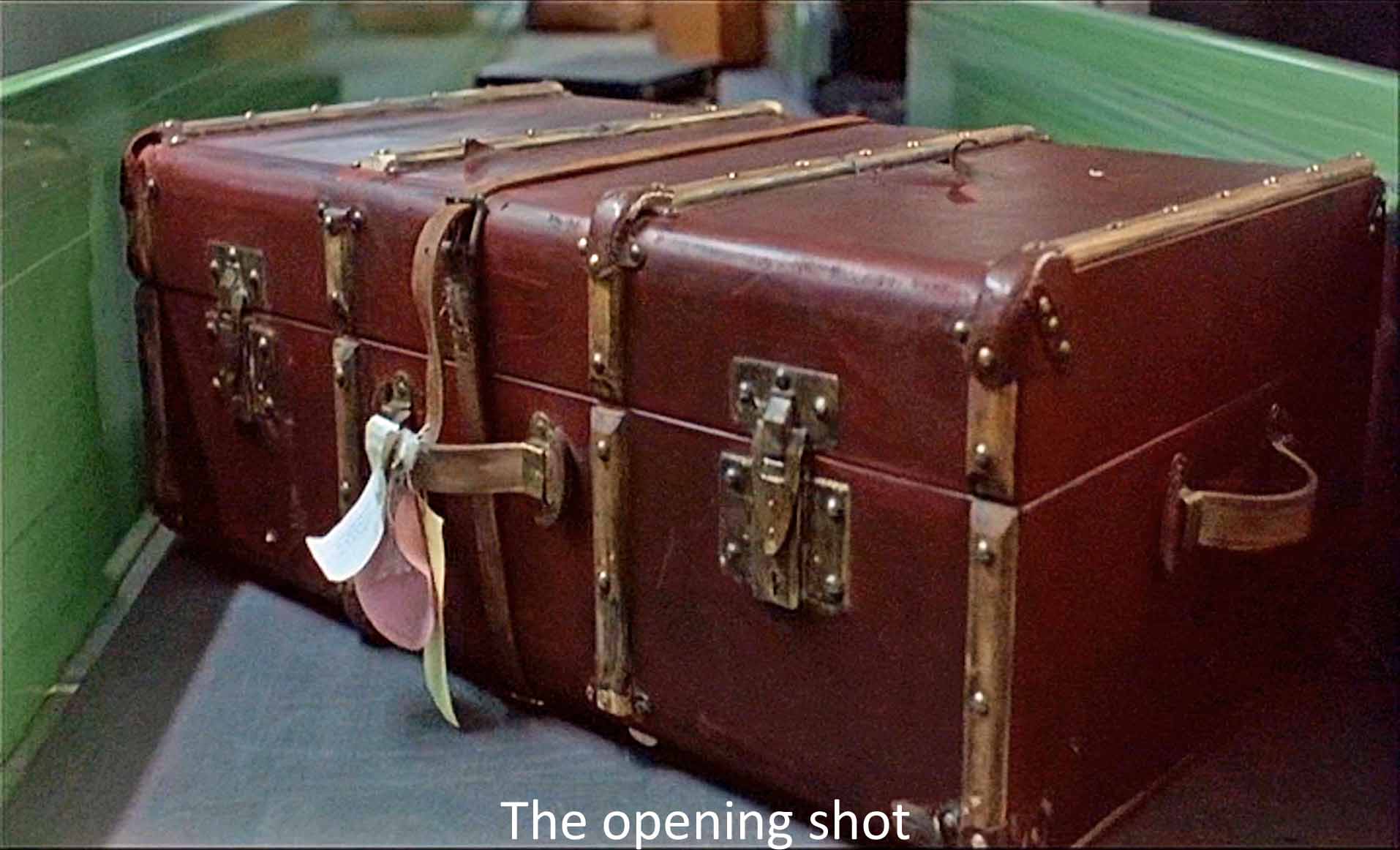

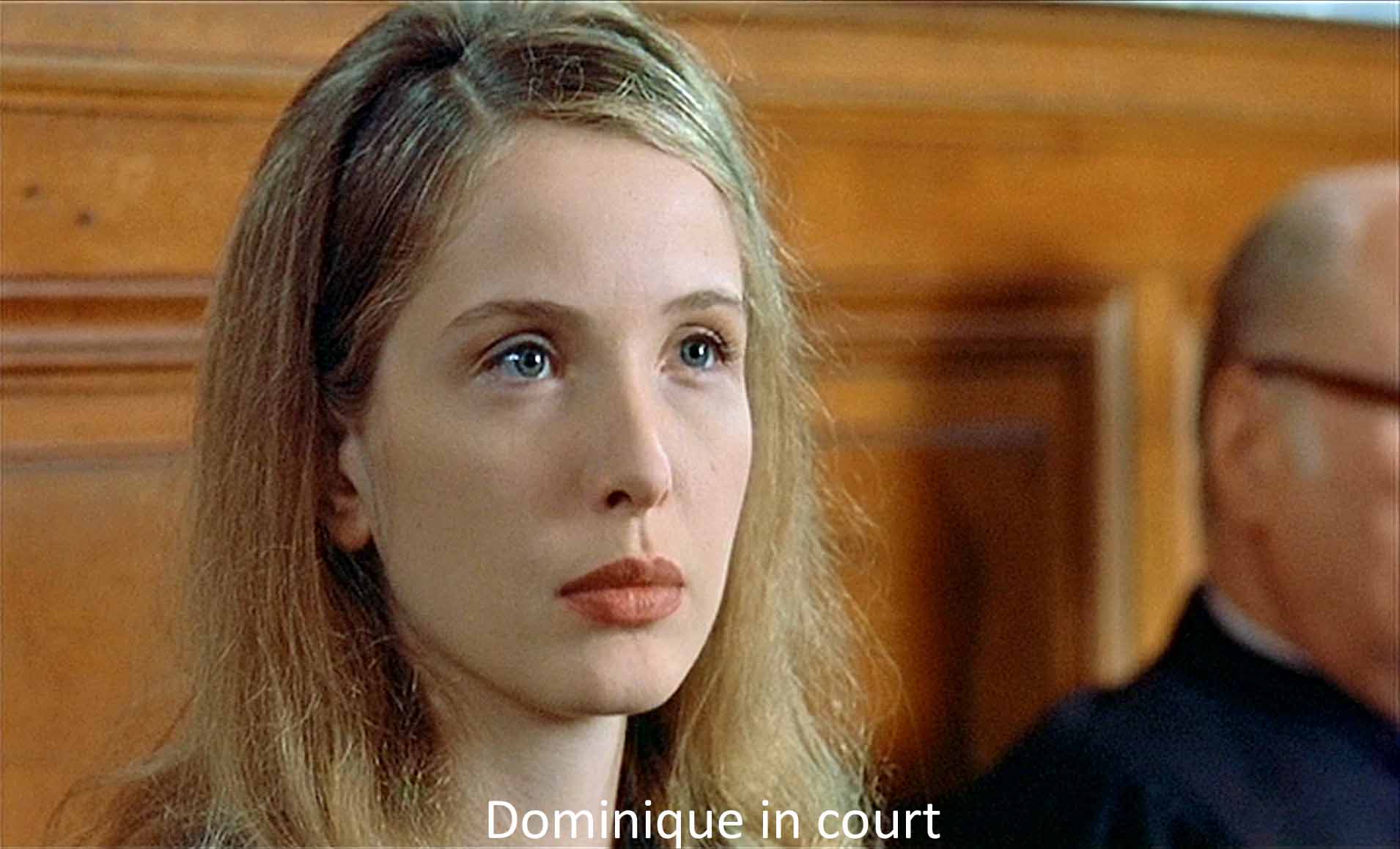

Polish emigré Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski), an award-winning hairdresser, owns a beauty salon in Paris with his wife Dominique (Julie Delpy). (Karol Karol translates as Charlie Charlie, and one needs to think of Charlie Chaplin when we are shown his shoes in the opening.) This shabby man is coming to divorce court where Dominique is dumping him, claiming (truly) that he was never able to consummate their marriage. (Kieślowski has said that the real subject of White is a woman humiliating a man.) She takes his money, the salon, his credit cards, their home, his belongings, his passport—everything except what’s in a battered old suitcase. When he hides out in their salon (and fails yet again to have sex), she starts a fire so that the police will arrest him. Karol resorts to playing Polish songs with tissue paper and his hairdressing comb in the Paris Métro. There, another emigré, Mikołaj (Janusz Gajos), recognizes a fellow Pole, befriends him, and sends him back to Poland, folded up in the suitcase. (Kieślowski makes this small trunk on the baggage carousel the opening shot—it’s important.)

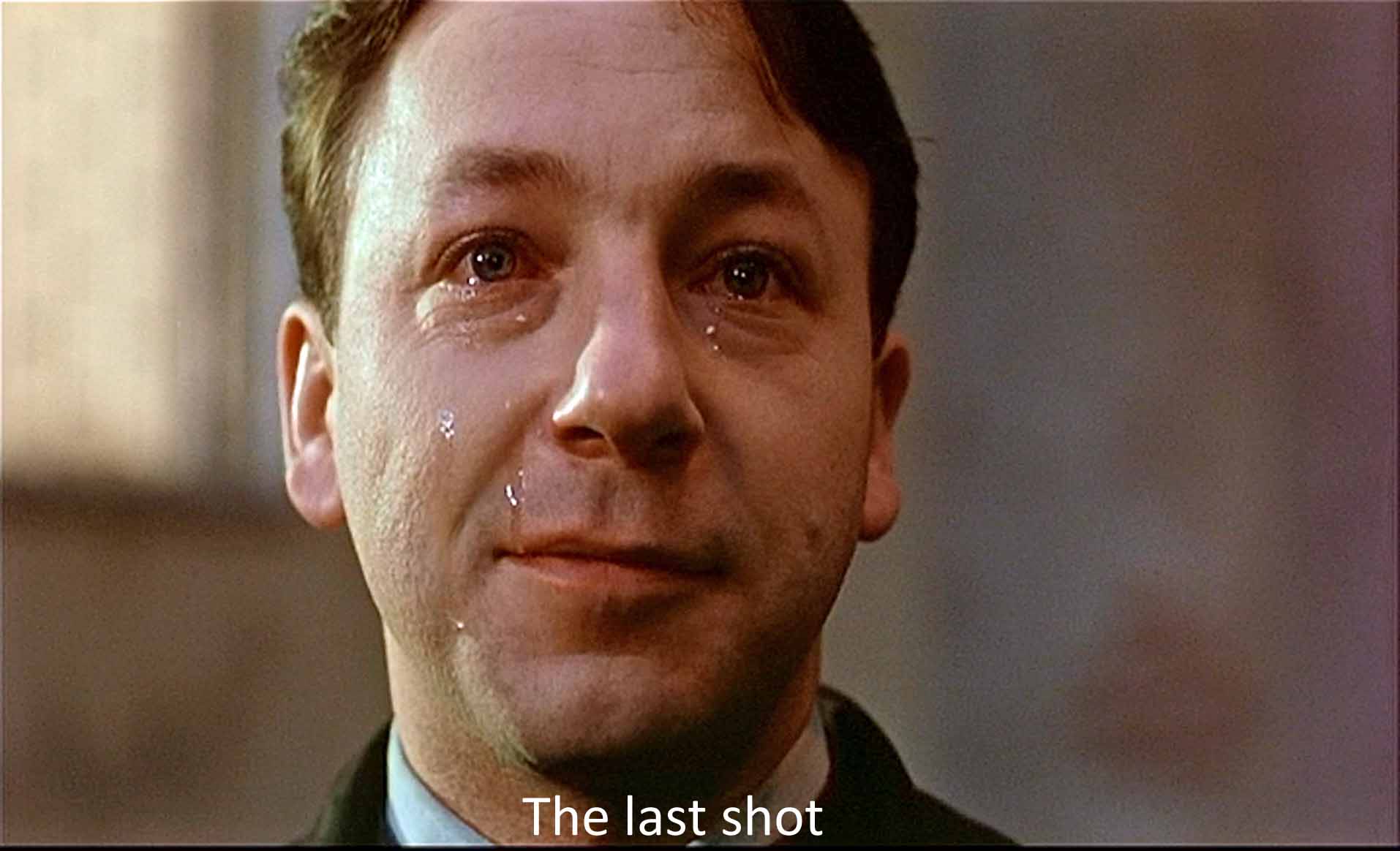

After a number of adventures, Karol becomes a rich businessman, one of the new plutocrats in post-communist Poland. He fakes his own death and lures Dominique to Poland to collect the riches he left her. The police arrest her for his murder. He too being subject to arrest, he has to hide. He can only stand outside the jail to see her through a window. (Kieślowski loves windows.) She signals by a little play in sign language that she does not want to get out of jail or leave Poland, she loves him, and she wants to remarry him. Tears roll down his cheeks, and he faintly smiles.

Kieślowski says this is an upbeat ending. Is it?

White stands for equality in the triad of French revolutionary values. Karol achieves equality in the end, but it is equality in the form of revenge. Revenge is an equalizer. It’s “getting even.” It makes the original wrongdoer and the original victim equal—but, here, at what a cost! And how odd to do it by the civil death of the revenger. This is a happy ending?

Columbia professor Annette Insdorf quotes a letter Kieślowski wrote to his producer about this ending: “I think this shot would make the end rise, and thus the film” (162). She summarizes the heroine’s sign language this way, “Her hands play out a little scene—no, she doesn’t want to escape from prison; she will stay so that they can remarry—as tears roll down Karol’s face. Kieślowski called this a happy ending because they both realize they love each other” (160). Oh?

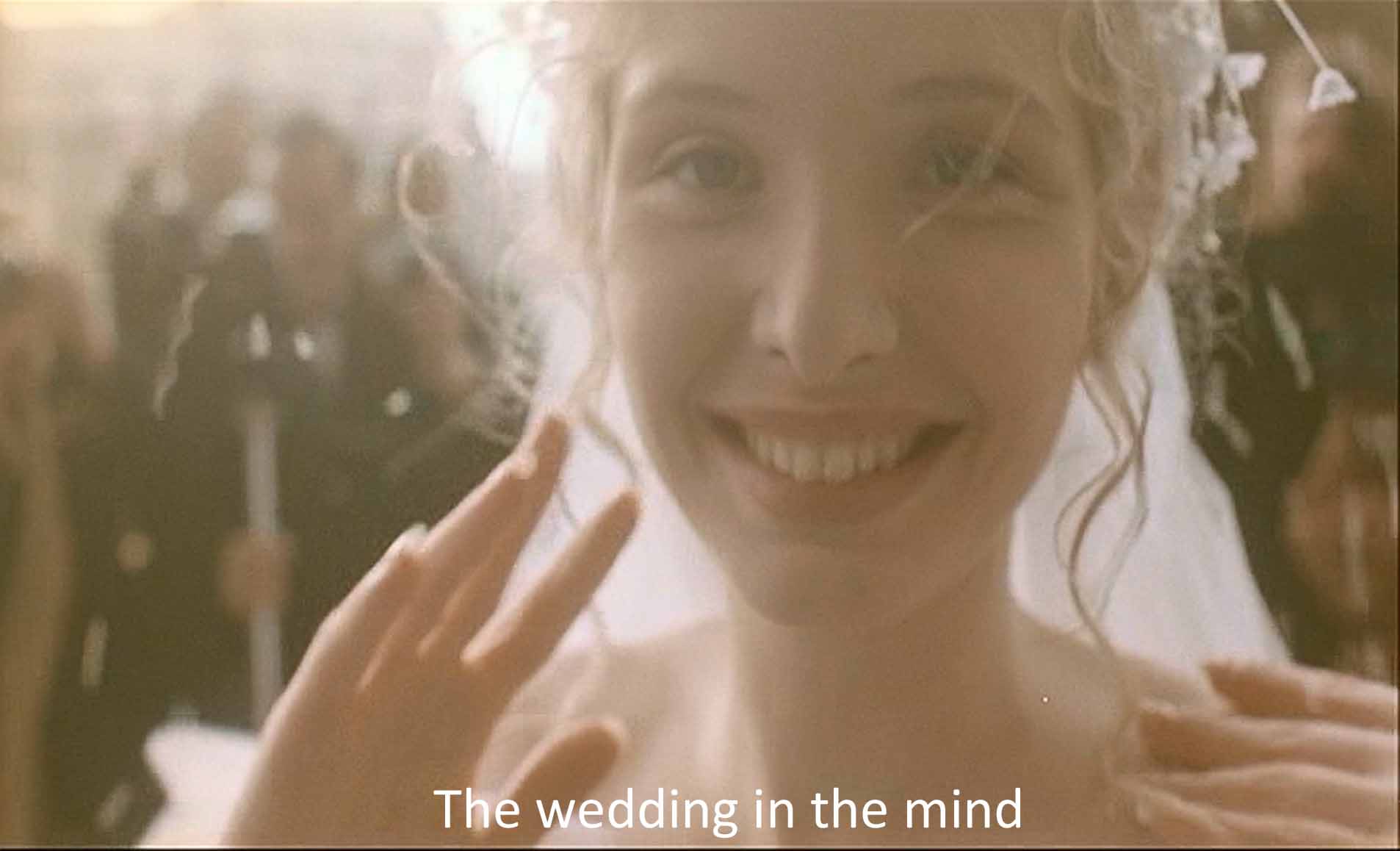

Insdorf quotes an unpublished paper: “They cannot reunite because he would have to `resurrect,’ to reveal that he didn’t die. He would be jailed and she would be set free” (Insdorf 162). In the end, then, he is imprisoned just as she is. They are equal, but through revenge and a revenge that injures in the same way that Dominique’s divorce suit in Paris did. The marriage at the end parallels the marriage at the beginning: sexless, the couple separated by law and by language. Hence Kieślowski repeats for the third time a flashback (flashforward?) of the wedding ceremony. Karol has recreated the marriage of the beginning, they are “even,” and Karol is right to cry about it.

One could argue otherwise that Karol does not “die,” because he does not fly off to Hong Kong—that was a feint. He remains in Poland. He can reveal himself and release Dominique and perhaps elude prison himself as one of the new plutocrats. After all, his lawyer says there is light (white) at the end of the tunnel. Who knows? I think Kieślowski wants to leave it ambiguous. He claims no more than that they love each other at the end. (Knowing how bitchy and dominating Dominique is, though, a cynical me can’t help wondering if her touching little play in sign language couldn’t be another ploy.)

That final mutual love seems a kind of rebirth or resurrection for Karol. For all three films in the trilogy, the regenerative power of love is a major theme. In Blue it was true. In White, Kieślowski makes it, of course, ironic.

In its non-ironic form, death-and-rebirth enacts one of the great mythic themes. Death-and-resurrection occurs in many of the great god-stories, Adonis, Tammuz, Mithras, Osiris, Persephone, Dionysus, and, of course, Jesus. Similarly, all the great epics have descents into an underworld, and at least figurative rebirths as a result, the Odyssey, the Aeneid, Beowulf, the Divine Comedy, Paradise Lost, Ulysses . . . And a host of lesser poems and stories have deaths and rebirths. Joseph Campbell included a journey into the underworld in his famous “monomyth” occurring at all times in all cultures.

Here Kieślowski makes death-and rebirth quite explicit. Mikołaj asks Karol to shoot him, and he does—but fakes it. The two of them then slide on the Warsaw ice like a couple of ten-year-olds—reborn as happy children, for the moment. Karol elaborately fakes his own death in order to trap Dominique, and then love brings him to life, but with tears. Then there are the figurative deaths-and-rebirths: Karol enters the underworld of the Paris Métro, then he seals himself in the “womb” of the suitcase, and he is dumped (reborn?) in the landfill, another underworld, where he is abused by thieves. The religious house of the peasant he buys land from is another kind of underworld in Campbell’s sense. Then Karol is reborn as a post-communist plutocrat, not only richer but smarter—and sexually potent.

Like the other films in the trilogy, White has a series of recurring ideas and images, “echoes” and “rhymes” within the film that give it an incredibly rich density:

Equality. Here it is surely ironic. White stands for equality in the triad of French revolutionary values. Kieslowski, however, has quoted an ironic Polish saying variously translated as, “Everybody wants to be more equal than everyone else.” “There are those who are equal and those who are more equal.” And Karol cries out in the French court, “Where is the equality here? Is the fact I don’t speak French any reason to refuse to hear my side?”

One of the major inequalities is the contrast between a posh Paris and a Warsaw impoverished by decades of communist economics: between rich France and poor Poland, between glamorous Paris and shabby Warsaw. Nothing in the film changes that.

White. It runs all through this film, varying from the heavenly to the basest: the pigeon shit, a white that falls from the heavens on a hopeful Karol; Dominique’s white wedding dress and her super-blondness (but dyed, perhaps a sign of her falsity); the toilet bowl where Karol vomits after the trial; Dominique’s car; the tiles of the Métro; the snow everywhere in Poland; the bust that looks like Dominique; the white glue that Karol uses to repair it, and no doubt many other whites. White is the color of purity, hence a "white" marriage is an unconsummated marriage. Similarly, tir à blanc, fire a blank, fire a “white” in French, is slang for a “dry” male orgasm. (Karol actually does fire a blank—at Mikołaj.) Conversely, after Karol’s and Dominique’s orgasmic climax in Warsaw, Kieślowski whites out the screen.

The music. In the Métro, Karol plays “The Last Sunday,” a sad “Polish tango,” and that tango music repeats throughout the Polish scenes. According to Wikipedia: “To ostatnia niedziela (Polish: “This is the Last Sunday,” 1935) is one of the long-time hits . . . A nostalgic tango . . . describing the final meeting of former lovers just before they break up, it was performed by numerous artists and gained the nickname of Suicide Tango, regarded as the perfect background music for shooting oneself in the head.” This tango repeats at many places in the film, styled for many different emotions, notably in the Métro, at the “Russian market,” when Karol and Mikołaj slide on the ice, in the peasant’s house, in Karol’s office, and so on.

The protectors. Two people help Karol in his resurrection. Mikołaj rescues him in Paris and sends him off to Poland. Once in Poland, once Karol starts his business, partly with Mikołaj’s money, Mikołaj becomes his chief aide and his stand-in when he fakes his death. He is like a father to Karol, a father whom, in the best oedipal tradition, Karol rescues from suicide. Then there is his brother Jurek (Jerzy Stuhr) who feeds him, nurses him, and tries to limit him to the hairdressing business. At the end, we see Jurek as a homebody, aproned and preparing bread and jam for Karol. If Mikołaj is like a father, Jurek is like a mother.

The comb. At first, it defines Karol as hairdresser, then as the lowest of street musicians. Finally, back in Poland with Dominique in prison, he looks through the comb. Is he seeing the bars of Dom’s prison? Or his own imprisonment? Or is he simply trying to see things differently?

The bust. As he leaves Paris, Karol buys a Watteauish plaster bust that apparently reminds him of Dominique. Just as the comb stands for him, the bust stands for her, first whole, then dumped and shattered, then patched up.

Birds. The pigeons at the Paris courthouse and the Warsaw dump, the pigeon that Mikołaj caresses in the subway—they are sometimes emblems of hope, sometimes emblems of the opposite.

The coin. In a short, “The Making of ‘White,’”, Kieslowski associates it with the furious urge to get rich in post-communist Warsaw. I think it is Karol’s link to France, stolen from him by a French telephone, won back by bullying a clerk in the Métro. He fights the airport thieves to keep it. At the Warsaw dump it defies gravity, serving as an omen of his ultimate success. Finally, he leaves it in the coffin with the Russian corpse as he pursues his revenge: no more link to Paris. Perhaps it refers to anything one is fierce about. The coin triggers two flashforwards, in which Karol imagines Dominique entering his apartment in Warsaw. Later, she will in fact, and they will have eminently satisfactory sex. He no longer needs the coin.

The wedding scene. Three times Kieślowski provides flashbacks to a wedding of Karol and Dominique (perhaps real, perhaps imagined). Apparently, it is a wedding in Paris, to judge from the background, pillars of the same court that granted the divorce. It is quite beautiful. It even has a sprinkle of white confetti to contrast with the pigeon droppings in the opening sequence. The first time we see this wedding it is Karol’s memory or wish as Dominique tears his marriage apart. The second time it is apparently Dominique’s, perhaps a moment of regret as she realizes how Karol has avenged her cruelty to him. But the third time, both appear in the scene—whose mind are we seeing? It may be either Karol’s or Dominique’s memory or fantasy. This final version gives us a truly loving and sexual kiss. Does this scene presage a happy ending, a remarriage? Perhaps it does, and we are seeing Kieślowski’s mind. But I think the scene creates an ambiguity, and I think he wants it that way. There are no tidy endings in this trilogy.

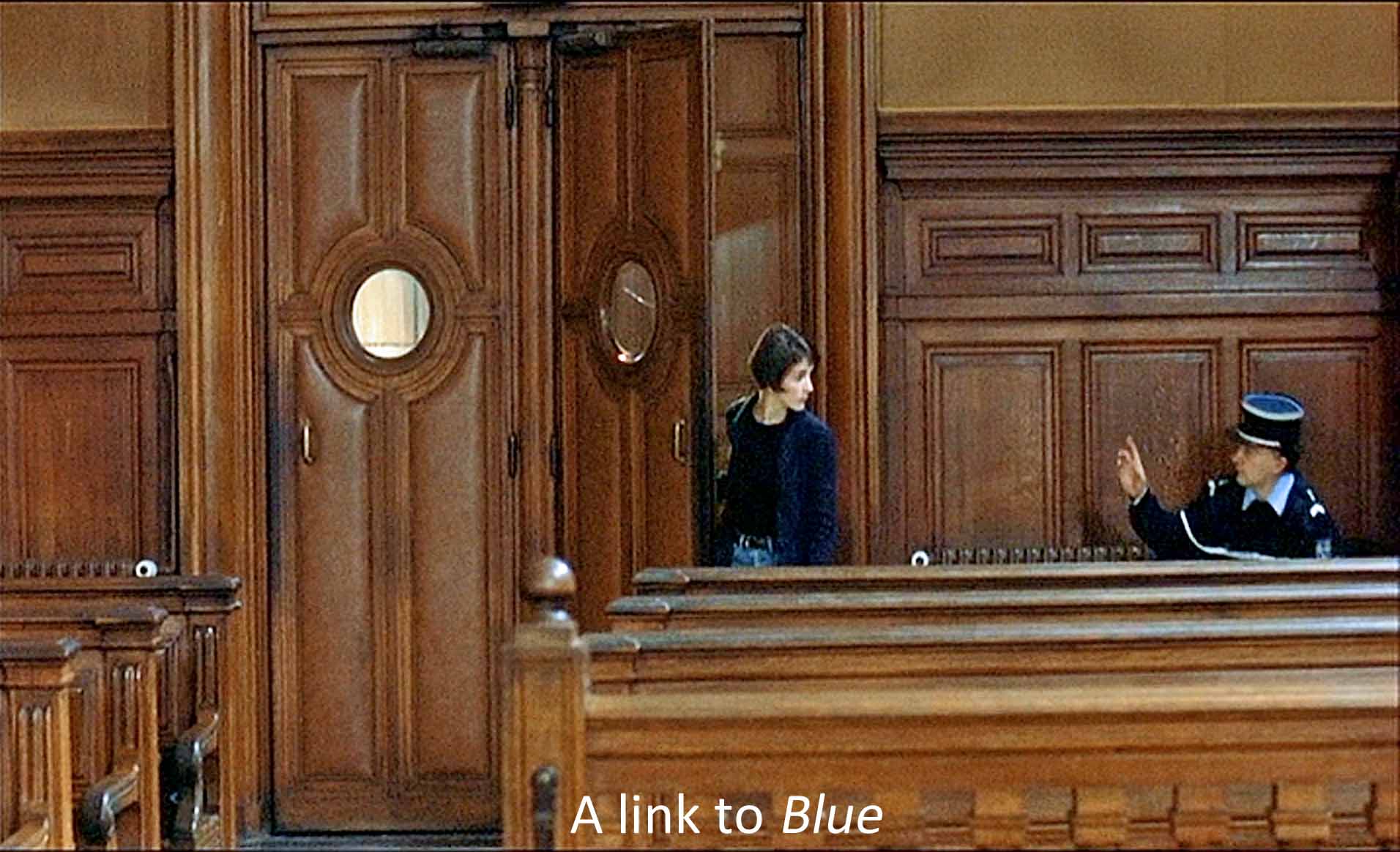

Windows. Kieślowski loves windows as both separating and connecting people: the window to the courtroom (which connects us to Julie from BLUE), the salon in Paris, Dominique’s window when she has sex, the salon in Warsaw, Karol’s spying on the land speculators, and on and on. A number of crucial transitions in White take place at windows.

The French lesson. Note the verbs Karol studies: to eat, to sleep, to leave—the basics but in the conditional. Note too how much his French has improved in his final meeting with Dominique.

Opera glasses. Twice Karol uses opera glasses to peer at Dominique, and both times they shift cinematographer Edward Klosinski’s camera into telephoto mode. We see through the opera glasses what Karol sees. We are complicit in his vision and in what he has done.

With this wealth of themes and recurring images, White is like the other films in the trilogy, densely rich in a Shakespearean way. One can pick any minute of the film and see in it things that reach backward and forward to the whole. One could describe that whole many ways. I think of White as a movie about equality in all kinds of complex senses: revenge, money, gender, marriage, and, as in all three films of the trilogy, love. But above all, I think of White as another of Kieślowski’s masterpieces.