Why do bad things happen to good people? The question is as old as 5000 BCE, the Old Testament Book of Job, and it is evidently with poor old Job that the Coen brothers started to work on their answer. Our 1967 Job is Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), a dull and inoffensive suburbanite who teaches physics in some Minnesota college.

Larry has moved his nutty, free-loading brother Arthur (Richard Kind) into the house. Arthur has a cyst on the back of his neck, and he spends all his time in the bathroom draining it. This sends Larry’s teen-aged daughter Sarah (Jessica McManus) up the wall, because she is obsessed with washing her hair and saving up for a nose-job. (“Nobody in this house is getting a nose job! You got that?!,” shouts frustrated Larry.) Otherwise, Arthur fills a notebook (the Mentaculus) with obscure drawings that constitute “a probability map of the universe.”

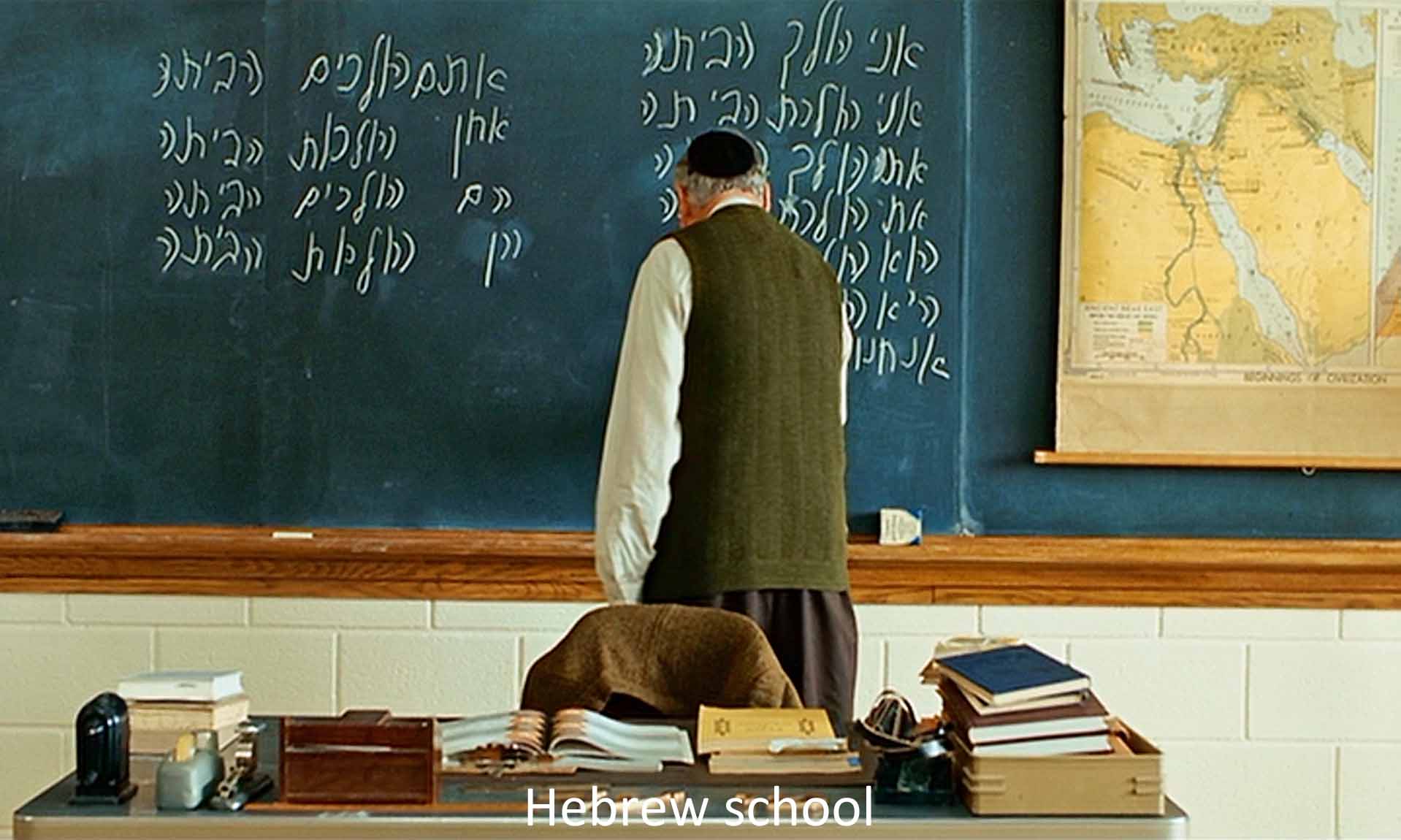

Larry’s son Danny (Aaron Wolff) is supposedly studying Hebrew to prep for his bar mitzvah, but he is really more involved with smoking and paying for pot. His only use for his father is to have him climb on the roof to fix the tv antenna so he can watch crummy television programs. Larry’s WASP next-door neighbor, a macho gun-toting type (Peter Breitmayer), threatens to build on Larry’s property line. Larry is up for tenure, but the chair of his department tells him the committee has been getting anonymous letters accusing him of “moral turpitude.”

As if all this did not suffice, Larry’s further troubles begin when his snide wife, Judith (Sari Lennick), announces that she wants a divorce so she can marry smarmy widower Sy Ableman—note the name, played by Fred Melamed). She has been having an affair with him (not sexual—she says. Hmm. And only in a Coen brothers movie would Fred Melamed be “the sex guy.”)

As the film goes on, Larry’s troubles snowball. His wife and her lover move him and brother Arthur out to the “Jolly Roger” motel (under the skull-and-crossbones flag, the sign of death). Someone from the Columbia record-a-month club keeps telephoning to collect from him. A Korean student Clive Park (David Kang) asks him to up a failing grade and leaves an envelope full of cash on his desk. When Larry tries to return it, the boy’s father threatens to sue him for “defamation.” Arthur gets in trouble with the police for homosexual soliciting, and Larry is saddled with big lawyer’s fees. He smashes up his car. At the same moment (why? “the just and the unjust”?), Ableman is killed in an auto accident. Larry’s grief-stricken wife expects Larry to pay for the funeral. Exploring “new freedoms,” Larry finds himself smoking dope with another neighbor’s sexy wife.

Finally, as his son, although stoned, manages to get through his bar mitzvah, Larry’s wife, moved by the ceremony, hints at a reconciliation. His chair tells him he has gotten tenure. Things begin to look up for Larry.

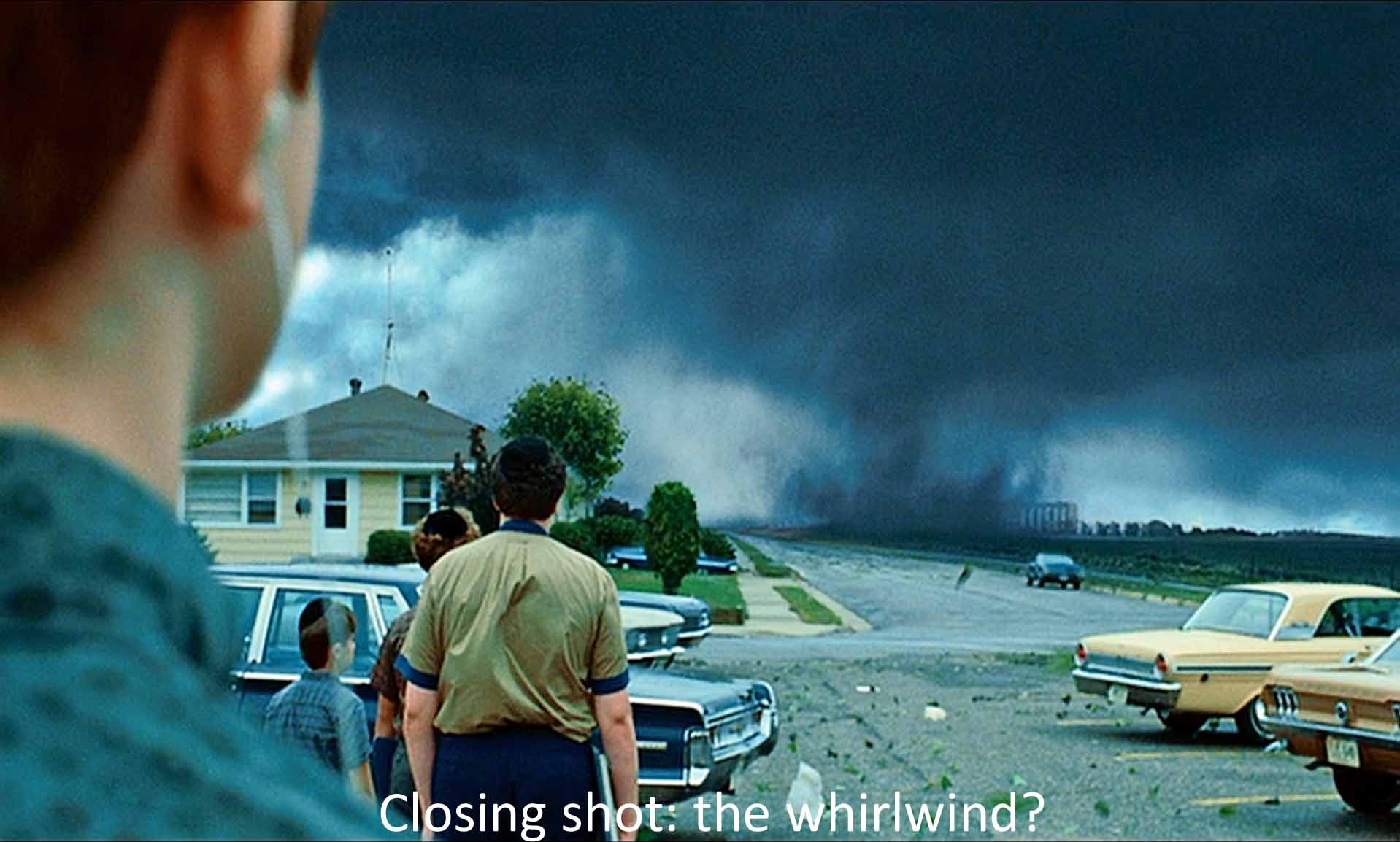

And then he fails. Confronted with a lawyer’s bill for $3000, he takes the Korean boy’s money and changes the grade. No sooner has he done so than the phone rings. It is his doctor who, ominously, wants to discuss his chest x-ray results with him. Meanwhile at his son’s Hebrew school, a tornado descends. God answering from the whirlwind as in the Book of Job? Certainly this final shot echoes the opening shot of snow falling, which itself tells us right off the bat who runs the weather.

Larry has failed some mysterious moral test—apparently—and here are the consequences. Again and again, the hero, his wife, his son, his daughter, and his students are questioned—tested. The movie abounds with tests. We begin with Larry’s pot-head son studying Hebrew for his bar mitzvah, which will be a test of his ability to read from the Torah. That’s cross-cut with Larry’s physical exam. Larry faces the test of getting tenure. Then we see his students trying to follow impossible math and physics in preparation for their exam.

His wife and Ableman test how grown-up Larry will be in response to their request for a Jewish ritual divorce. The Korean student’s bribe poses a moral test as does the seductive next-door neighbor. So too does his macho neighbor with his trespassing. And throughout there is the ultimate question, How will this good man, Larry, cope with all these bad things happening to him?

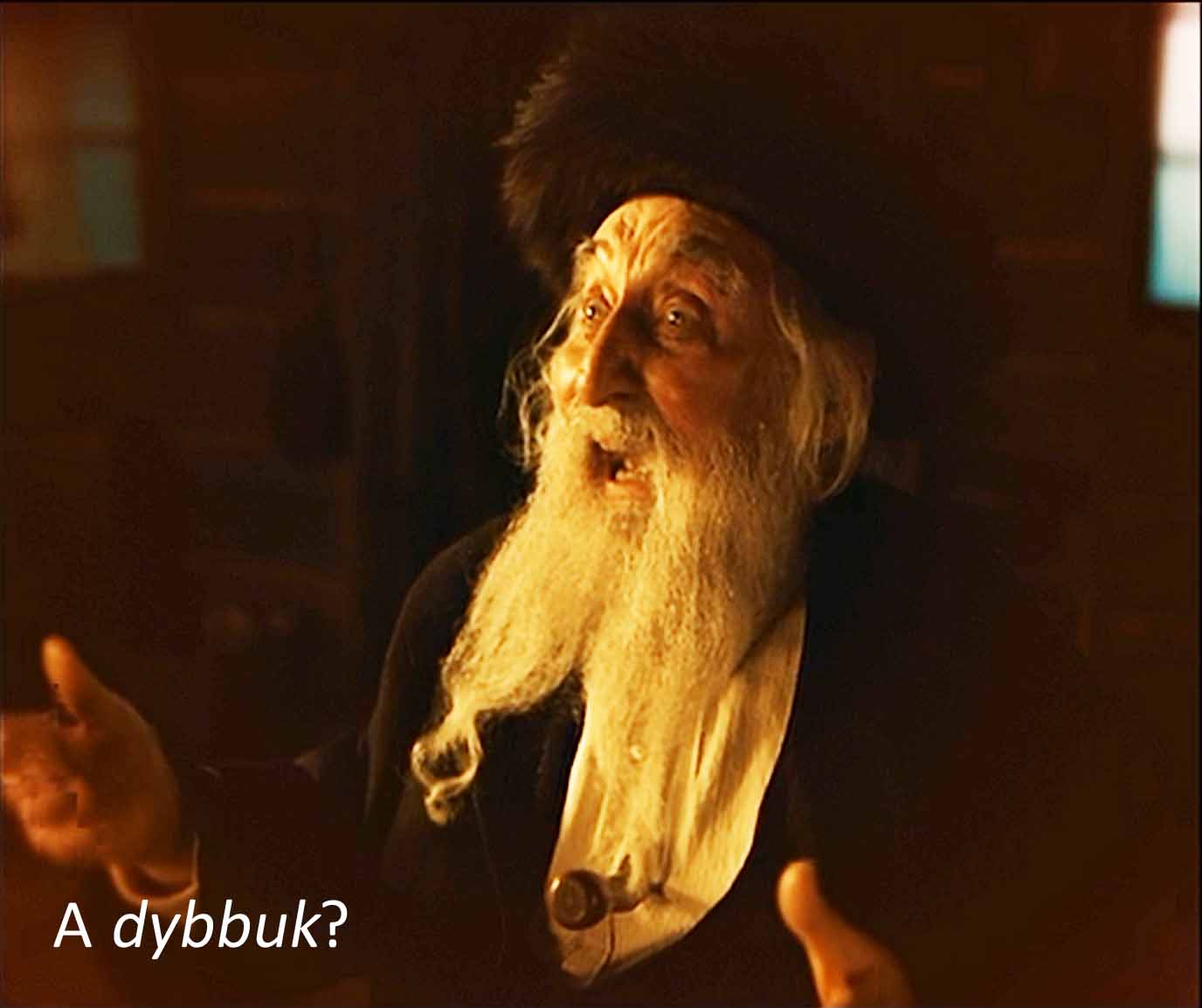

All this testing began with a folktale which incongruously begins the movie A Jewish peasant and his wife are visited by an old, old man (Fyvush Finkel, a legendary actor in the Yiddish theater). He had helped the peasant when his cart broke down, and the husband had invited him into the house, but the wife thinks the old man is dead and their visitor is really a dybbuk, a malicious ghost. To test the creature, she stabs him in the belly. He begins to bleed. Is he a man? Or is he an evil spirit who will bring down bad things on this family and their descendants (who may include our hero Larry)? We’ll never know. The Coens say the folktale has nothing to do with the rest of the movie, but that's just the Coens smokescreening. What this seemingly unconnected folktale has introduced are the three core themes of this movie: worshipping God in a ritualistic (obsessive-compulsive) way; bad things inexplicably happening (are they by God?); and a constant testing that is painful, even killing.

These last two are the great themes of the Book of Job. Job’s God answers, in effect, Who are you to question me? I am all-powerful. I do what I please. If I choose to test you, I will. Get used to it. “Then the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind and said ‘Who is this that darkeneth counsel by words without knowledge. Gird up now thy loins like a man; for I will demand of thee and answer thou me’” (Job 38:1-3). All-powerful—that’s why the movie begins and ends with weather.

Consider us demanded of. How will we understand this movie? How will Larry and all of us cope with woes and testing? To muddle through, these humans deploy various systems for solving the mystery of human suffering: medicine, that is, Larry’s physical exam; the Torah encoded in the mystifying Hebrew language; Larry’s mathematical physics; the Kabbalah; the touchy-feely psychology that Sy Ableman puts out; secular law and religious law; dreams of sex or escape; the rules of a record company; the record title Santana Abraxas that brings in Gnosticism—Abraxas is a Gnostic deity that Jung enthused about; the ritual of the bar mitzvah itself that leads to reconciliation; the mysterious message of the third rabbi. Even doing nothing—as Larry insists to the record club man: “I didn’t do anything!” Even that is a tactic for dealing with suffering.

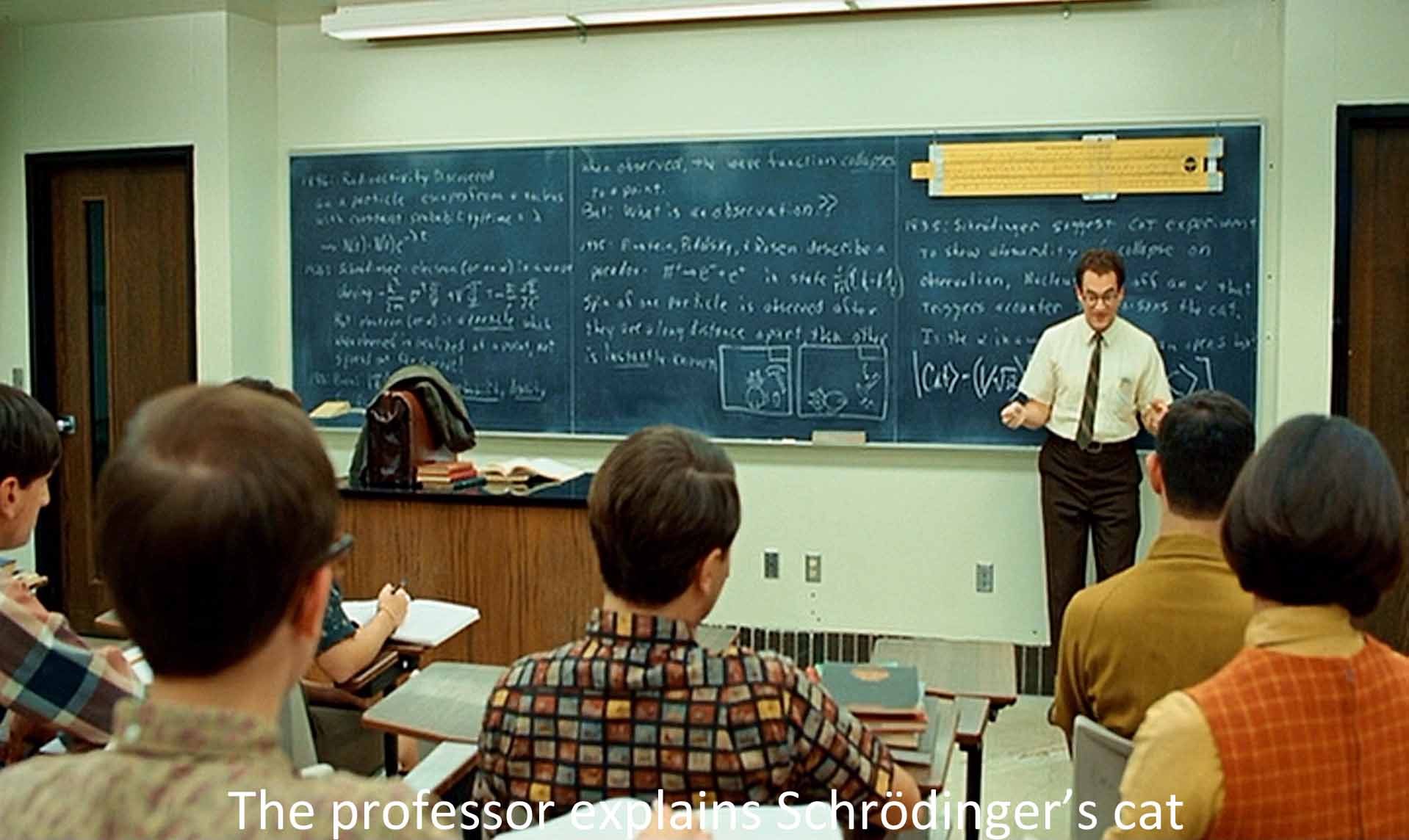

As a whole, this film fits a traditional Jewish genre, the story of a schlemiel. Then there are embedded in it the various Jewish fables, “that well of tradition to draw on . . . stories that have been handed down from people who had the same problems” (recommended by a woman with braces on her legs). The Coens provide fables like the cryptic folktale that began the film or the puzzle of the goy’s teeth or the riddle of Shrödinger’s cat: Larry frantically scribbles equations on the blackboard, but the upshot is that we don’t know whether the cat is dead or not dead. Larry develops the ultimate fable in a giant blackboard full of incomprehensible math: “The Uncertainty Principle. It proves we can’t ever really know what’s going on. So it shouldn’t bother you. Not being able to figure anything out. Although you will be responsible for this on the mid-term.” How delightfully Kafka-esque. (Another Jewish teller of tales with a dark and comic outlook much like the Coens’.) All these systems, says the film, people use to understand and cope with what seems a perverse, capricious, but all-powerful deity. And they fail.

A Serious Man is about suffering, about testing, but also about the fallibility of human beings using various systems to cope. The film relentlessly associates Jewish traditions with repellent old men and women—mortality staring us in the face. All the mortals in A Serious Man know less than they think they do. Larry’s doctor first pronounces him healthy, but later calls with a scary message about his health. Larry bores his uncomprehending students with all his math. The rabbis are no help. Rabbi Nachtner concludes his mysterious parable of the goy's teeth: “Helping others, couldn't hurt.” But, when Larry asks, “What happened to the goy?,” he answers “Who cares?” Larry tries logic to show the Korean how inconsistent his claim of defamation is, but the Korean outploys him by saying simply, “Accept the mystery.”

If anybody in A Serious Man has the answer to bad things happening to good people, it is the Coens themselves. They have a mannerism that generates many of the puzzling details in their movies, details that puzzle us as the mystery of suffering does. They like to make images out of verbal phrases. For example, Uncle Arthur has a cyst on the back of his neck that he keeps draining. That makes him a pain in the neck. Larry takes care of his brother, acting out, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” The movie proper begins (after the folktale) with two images of ears, that is, things going in one ear and out the other. Larry’s son makes him fiddle with the tv antenna on the roof, and I suppose that makes Larry a fiddler on the roof hoping for a message from above. He watches from the roof (long enough to get sunburnt) nude Mrs. Samsky sunbathing. That echoes the biblical story of David and Bathsheba (2 Samuel 11). Jessica’s constantly washing her hair translates into her trying to get her pesky uncle and brother out of her hair. Larry has a dream in which Ableman bangs his head against the blackboard. Presumably Sy is trying to knock some sense into Larry’s head. In Rabbi Nachtner’s story, the goy has a message (in Hebrew) on his teeth. Since he is not a Jew, he is surely “lying in his teeth,” i.e., lying boldly. The Nazi or KKK slogan, “Kill all the Jews” gets translated into Larry’s dream of his WASP neighbor’s hunting Jews. “I’m going to the Hole,” says his daughter—I’m not sure I want to translate that. Larry’s plea to the record company man, “I didn’t do anything,” summarizes his behaviour throughout: he doesn’t do anything to get tenure, to keep his wife, to have sex with the neighbor, to correct his son or daughter, or to be sent the Columbia records. The tornado that threatens Danny at the end echoes, “Then the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind.” There are no doubt many more of these verbal-to-visual puns that I didn’t catch. As in Barton Fink, they have much to do with the Coens’ notion of making a film, starting with their extra-careful script. In the beginning was the word. The word is made flesh, as it were. The Coens are creators, and if there is a God in A Serious Man, it is surely Joel and Ethan Coen.

Five times A Serious Man gives us the answer to the question it and the Book of Job ask: how do you act toward an all-powerful trickster God who makes bad things happen to good people? The first comes even before the picture starts, with the epigraph from the medieval rabbi Rashi: “Receive with simplicity everything that happens to you.” Later the Korean father dismisses Larry’s logic by saying, “Accept the mystery.” Then the three rabbis (versions of Job's three “comforters”) provide versions of this answer. The naive junior rabbi (Simon Helberg) says, see the wonder in things, get a new perspective. Nachtner, the oily senior rabbi (George Wyner) answers with the incomprehensible story of a message in a goy's teeth. He ends by quoting himself: “Nachtner says, look. The teeth, we don't know. A sign from Hashem? Don't know. Helping others . . . couldn't hurt.” “Hashem doesn't owe us the answer, Larry. Hashem doesn't owe us anything. The obligation runs the other way.” And finally the ancient Rabbi Marshak (Alan Mandell) addresses Larry's pot-head son who has managed to get through the bar mitzvah though stoned. The old man recites the opening of the Jefferson Airplane song that has been running all through the movie: “When the truth is found to be lies / And all the hope within you dies . . . Vot den?” He lists the Jewish members of the Airplane (balking at the goy) and ends by giving the kid his forbidden Walkman. The ancient teacher says simply, “Be a good boy.”

Anyway, that’s the answer: no answer. Why do bad things happen to good people? They just do. Try to be a good human being—that’s the best you can do. “Couldn’t hurt.”

And do the Coens themselves provide their own, sixth answer in the “Easter egg” at the end of all the credits? “No Jews were harmed in the making of this picture.” Which follows upon the more usual, “No animals were harmed,” a curious and questionable juxtaposition. But both are claims the brothers did no harm.

And they didn’t, even though this is the most autobiographical of all their films, although, of course, the Coens, with their own trickiness, dismiss the idea that the film is autobiographical or that the opening folktale has anything to do with the rest of the movie. They just put it in to set the mood. (Give me a break!)

But they went to a lot of trouble to shoot the film in Bloomington MN, the Jewish suburb where they grew up. (They had to mount tv antennas on all the houses that now have cable, and they had to digitally remove trees that had gotten bigger.) Larry’s house has the same layout the Coens grew up in. And many of the minor characters have the names of people the Coens grew up with, the boys who hang with Danny or Mrs. Samsky. The Hole, where Sarah goes, is a University of Minnesota sports bar. The lawyer recommended for Larry, Meshbesher, has a particularly annoying tv ad. The brothers were, like Danny, fond of Larry Storch and “F Troop” on tv. But in interviews they deny the autobiographical stuff.

Why are artists so reluctant to let us see how their minds work? Is it like Sherlock Holmes? When you see how it’s done, it will look absurdly simple? Maybe. But all the artists I know get very uptight if someone tries to analyze their work or their thought processes. An explication like this will be most unwelcome.

Sorry about that. It seems to me that people come out of a movie like this saying, Why was that folk tale there? What does the tornado mean? Why the business with the tv antenna? With the sexy neighbor? And so on. People want to make sense of a film, that is, they want to see how the different elements (particularly the most puzzling) fit together. (You see questions like these all the time in online discussions of movies.) And this questioning is not so different from Larry’s or Job’s trying to make sense of a world in which bad things happen to good people and the being in charge (the director, so to speak) seems arbitrary and capricious.

Like Barton Fink, then, this film is also about filmmaking as well as about world making. And as always with the Coens, what started out as a slightly perplexing but very funny movie ends up by being not just funny, but dark, quirky, and very, very profound.