Start with the title. It says a lot about what follows. Eyes without a Face (Les yeux sans visage): this film has many shots of eyes, eyes staring into other eyes, eyes beneath a tense, sweating brow, eyes above a surgical mask, above bandages, behind the smooth, plastic mask the heroine wears. Eyes give us knowledge, and knowledge, in this film, gives power and prestige, even a certain invulnerability.

We often cannot see the faces. We cannot tell what thoughts or feelings are behind those eyes or, sometimes, even who is behind them. Eyes are a source of knowledge, but faces are our very identity, our being. In a sense, you can read this film as contrasting eyes with faces, knowledge with being.

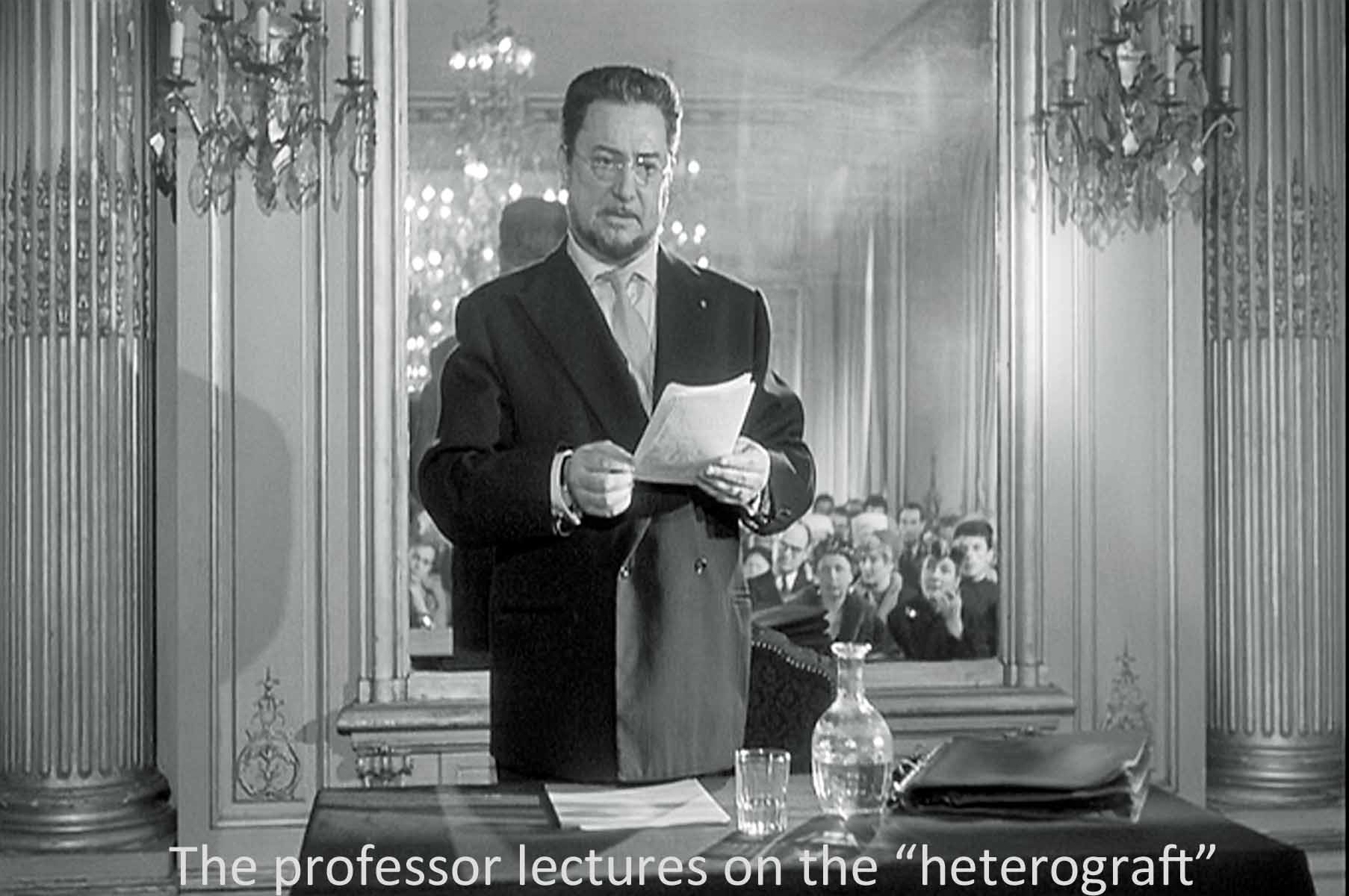

Knowledge here comes in the form of the power of a doctor and his use of medical terminology that goes over heads of us laypeople. (Remember the fun Molière had in Le Malade imaginaire with doctors’ mumbo-jumbo.)

Knowledge and being: that’s the essence of the doctor-patient relationship, isn’t it? The doctor has a fund of knowledge that he or she is supposed to apply dispassionately to the patient. The patient just wants to go on living in good health—to be. And in this film, compassionate being trumps dispassionate knowledge.

All of us have a certain fear of medical science. After all, doctors know and foretell the worst things that can happen to us. (Think of the “white-coat" effect, the rise in blood pressure in the doctor’s office.) This film plays on that fear—after a familiar horror movie opening.

After the eerily lit road under the credits, the first thing we see is in fact a face, the face of Louise (Alida Valli). We don’t yet know her name or anything about her except that she is having trouble seeing. (Later, we will realize that she is having trouble seeing morally as well as visually.) She is driving a car, she is anxious and tense, then we see that she has in the back seat of her cheap little “deux chevaux” a crumpled figure in a trenchcoat and hat. The darkness, the road, the strange lighting—this is as much a film noir as a horror movie typical of the genre.

Louise proceeds to dump the thing in the trenchcoat—and now we see it’s a corpse—in the Seine. Louise’s face gives her an identity. The corpse has no face and no identity. In fact, we shall shortly see her mis-identified.

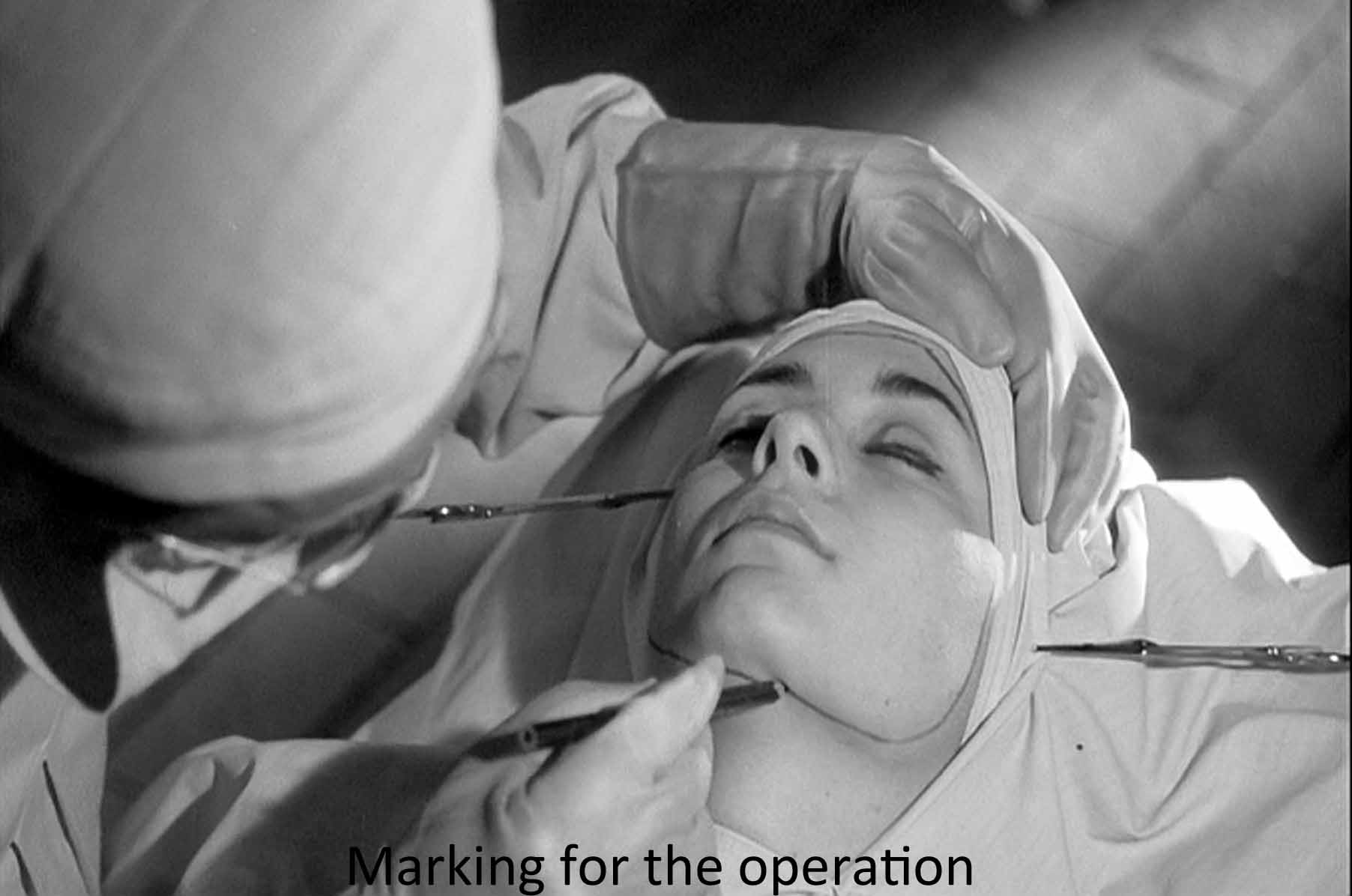

Cut to a lecture hall and many faces in the audience, then, finally, the rather forbidding face of the lecturer: Professor and Doctor Génessier (Pierre Brasseur). He is describing the “heterograft,” the taking of tissue from one person and giving it to another. As he finishes his talk and leaves, he is summoned to the morgue to identify a body. The police are puzzled. This corpse had a mutilated face and blue eyes, like the professor’s daughter when she disappeared two weeks previously, but why naked, why in a trench coat? And the facial wound looked as though a scalpel had done it. But the professor (falsely) identifies the corpse from the opening scene as his daughter who disappeared two weeks previously. As he leaves, the professor brutally dismisses a man who pleads that this might really have been his daughter—whom we learn later the doctor has murdered.

Once home, he goes to visit his daughter Christiane (Edith Scob). She is hidden away upstairs in an all-white room with doves and music, in an all-white peignoir. She hides her face in her pillow—we never see it, although her father does. He orders her to get in the habit of wearing her mask, which Louise dutifully brings. It is smooth plastic like the face of a store mannequin, and the effect is scary. Behind it we see her eyes, eyes without a face.

Her doctor-father promises he will “succeed,” and I think most of us surmise what he wants to succeed at, especially after we see Louise go to the student quarter and pick up a young woman. Certainly Christiane figures it out as she tiptoes around the house and peeks at what the doctor and Louise, his devoted nurse/assistant/secretary/mistress(?), are up to. Incidentally, we learn that the doctor “succeeded” with Louise, restoring her face, leaving only a scar on her neck that she conceals under a pearl choker.

The doctor promises his daughter, “You will have a real face,” “un vrai visage.” Joan Hawkins has found that “vrai visage” was a phrase used during the Nazi occupation of France in World War II, a motto posted on the office dealing with Jews. “Nous combattons le juif pour redonner à la France son vrai visage.” We fight the Jew in order to give back to France her true face (Hawkins 70). The doctor reminds Ms. Hawkins (and me and others) of the Nazi doctors like Mengele who experimented on prisoners in the name of racial purity. Linking this father to the Nazis takes a jab at the autocratic father of French tradition and the cinéma de papa that the Cahiers critics made fun of.

The doctor is, however crazy, devoted to his daughter. He is consumed with guilt at having caused the auto accident that cost her her face. (He was “driving like a lunatic.”). And he is not simply heartless. We see him being kind to a boy and his mother in his clinic. This is a complicated father-figure.

That patient was a boy, though, unlike the young women the doctor mutilates. Does that matter? Horror movies always play on our psychological fantasies, and it’s not hard to identify the fantasy behind this one. We must repair this damaged female by pasting a body part on her. In dreams and fantasies—and horror movies—the face often stands for the gender-identifying parts further down. Analysts call this “displacement upward.” Yet to repair one woman, we must damage others. Women are inevitably damaged. The mother-figure, however, Louise, has been successfully repaired, and now she can participate in damaging other women—the students she picks up. A complete woman is dangerous. At the end, when Christiane tries to stop the carnage, she stabs Louise precisely in the scar left from the operation that gave her back a face. In that same vengeful ending, the doctor loses his face. Poetic justice.

In the last, telling shot, Christiane frees the caged dogs on which the doctor has been experimenting, to which she has been kind, and she frees the doves that have mirrored her own captivity. She walks off surrounded by doves—and doves are sacred to Venus, the goddess of love. In her robe, she looks, to my eye, rather like the statues of St. Francis one sometimes sees in gardens, a robed saint with birds. It is her compassion that brings both mercy to a victim and justice to the medical killers. As so often in horror movies, the idiotically risky and bumbling efforts of the police and her fiancée have accomplished nothing.

To some extent, Christiane balances her father. He is dispassionate; she is compassionate. He is merciless; she is merciful. At the end she is a goddess of love, who dispenses both mercy and justice. But the film is not that simple. Earlier, in a curious sequence, she had shown kindness to the dogs her father experiments on. But, in the moments after, she did not release the victim about to be operated on, perhaps because that victim screamed when she saw Christiane’s mutilated face. She went had gone along with the mutilation of this girl when she thought her father would “succeed.” It is only when she decides that he cannot succeed that she foils his plans and brings down justice on the two murderers. Her need to be drives both actions equally. She is a complicated character, and this is a complicated film, not just a “horror movie.”

Director Georges Franju did not make many feature films, at least many that are well-known. He is probably most famous for having founded with Henri Langlois the legendary Cinémathèque Française. It (and Langlois’ collection on which it was built) survived World War II, when the Nazis decreed that all films made prior to 1937 should be destroyed. After the war, it became the headquarters for the Cahiers critics and later the nouvelle vague filmmakers. Next to Eyes Without a Face, his best-known film is the documentary Le Sang des Bêtes (The Blood of Beasts, 1949), a documentary on some of the slaughterhouses of Paris. The film is bookended with scenes of the outskirts of Paris with railroads and junkheaps and flea markets. The scenes in the slaughterhouses are both sickening and poetic like the Grand Guignol scenes in Eyes Without a Face. It is a stunning film and, believe me, one viewing is enough to make you a vegan.

But Eyes Without a Face itself is enough to guarantee Franju a place in the pantheon of film greats. It is a horrifying, but also a lovely and poetic film, a complicated challenge to medical and patriarchal power, and, finally, a tremendously satisfying movie experience.