Blue = liberté. But Kieślowski treats liberty ironically in this film. It begins as an auto crash kills the famous composer-husband, Patrice de Courcy, and Anna, the young daughter of the heroine, Julie Vignon, who survives the crash. (She is played wonderfully by Juliette Binoche expressing non-expression through most of the picture.) Severely injured, she is hospitalized. (When she finally wakes up, Kieślowski does an amazing shot of her eye with a 200 mm. lens.) Overwhelmed with grief, she breaks a window to distract a nurse, and tries to commit suicide, but she cannot. On her discharge, she cuts herself off from home, belongings, a lover, locale, memories, history, desire, relationships, even casual relationships—everything. She is as pure an instance of liberté as any Libertarian or survivalist could wish. And it doesn’t work.

You will want to note what makes it fail—sexuality. Immediately after she recovers from the crash, Julie invites into her bed Olivier, a man who has long been in love with her (Benoît Régent). That interlude, tender though it is, has no effect. She gets rid of everything, including Olivier, and retreats into anonymity in an anonymous apartment near the Rue Mouffetard in the heart of Paris. (Ironically, for a woman trying to lose memory, this is a street with a rich history that dates back to Roman times and beyond.)

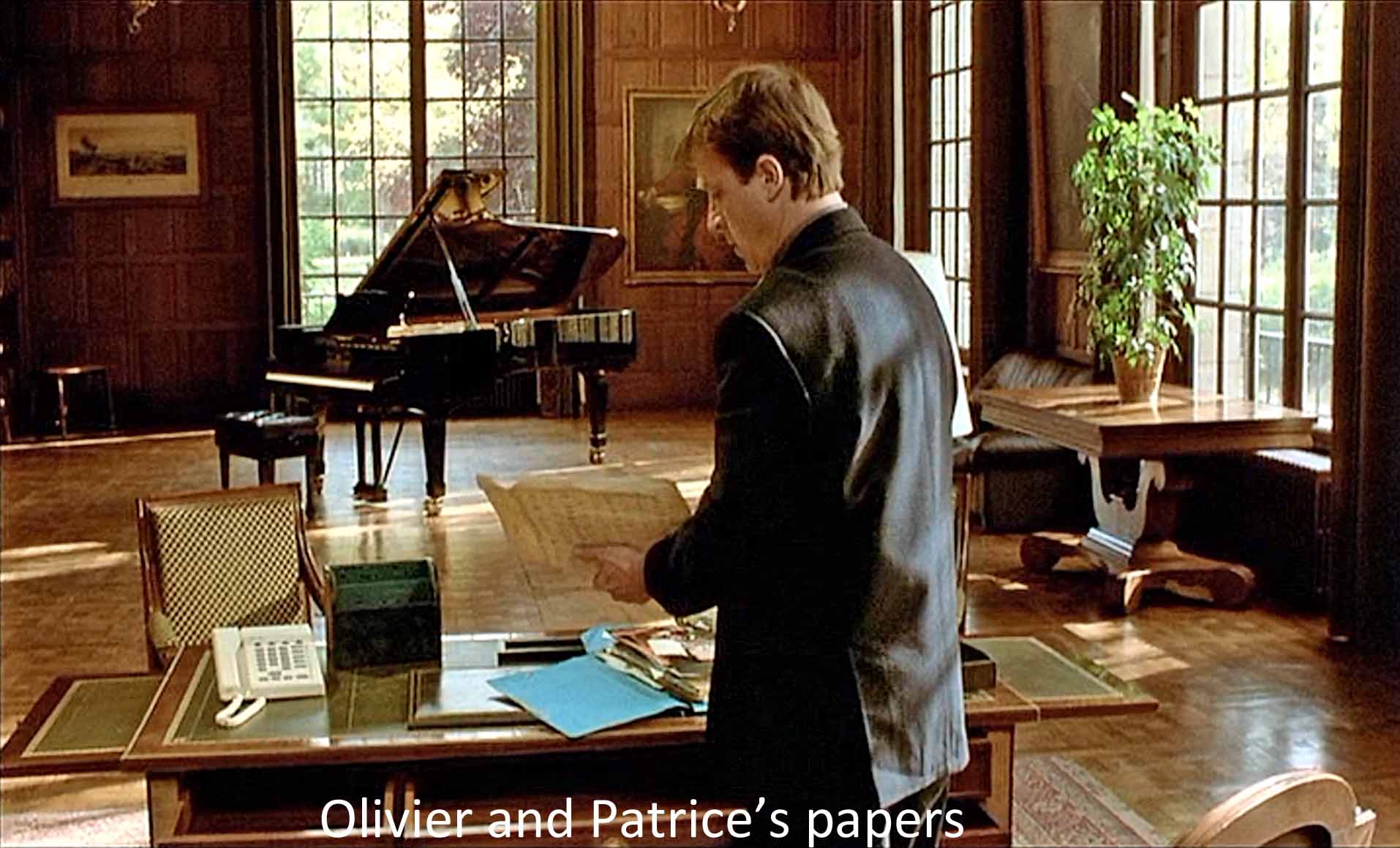

There she lives in isolation, until she is befriended by Lucille, a sex worker who lives downstairs (Charlotte Véry). In Julie’s apartment, a rat gives birth to a litter. (Is it seven baby rats like the seven puppies or the seven survivors in Red?) A borrowed cat and Lucille help her end her involuntary mothering, but Julie is deeply distressed by the episode. Lucille in turn issues a distress call in the middle of the night that drags Julie into a world of outré sexuality. At Lucille’s sex club, she happens to see a television show featuring Olivier who had been her husband’s assistant. From Olivier’s showing her husband’s papers, she learns that he had had a mistress for the four years before his death, a mistress whom he loved. Julie hunts down the mistress, Sandrine, a lawyer (Florence Pernel). She is pregnant with Julie’s husband’s child, and that changes everything.

I don’t believe there are such things as spoilers so I will tell you that it is sexuality that brings Julie out of liberté and back to life. But it is sexuality in the broadest sense, including procreation. It is sexuality in the sense spoken of by Paul in I Corinthians 13, the text with which the movie concludes: "Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not [love], I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. And though I have the gift of prophecy and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge, and . . . have not [love], I am nothing."

Love vs. liberté. That Biblical text (in its native Greek) is the chorale from the great piece that Julie’s husband was composing at the time of his death, Concerto for the Unification of Europe. The film is ambiguous about Julie’s contribution to the work. She may have written part or even all of it. But now, in the finale, she and Olivier complete it. And it is with the Concerto and the passage from I Corinthians and Julie’s connecting with Sandrine and Olivier and the unborn baby that the film ends.

That is a broad outline of the film, and, if you haven’t yet seen it, I suggest you stop reading here. What follows won’t make much sense.

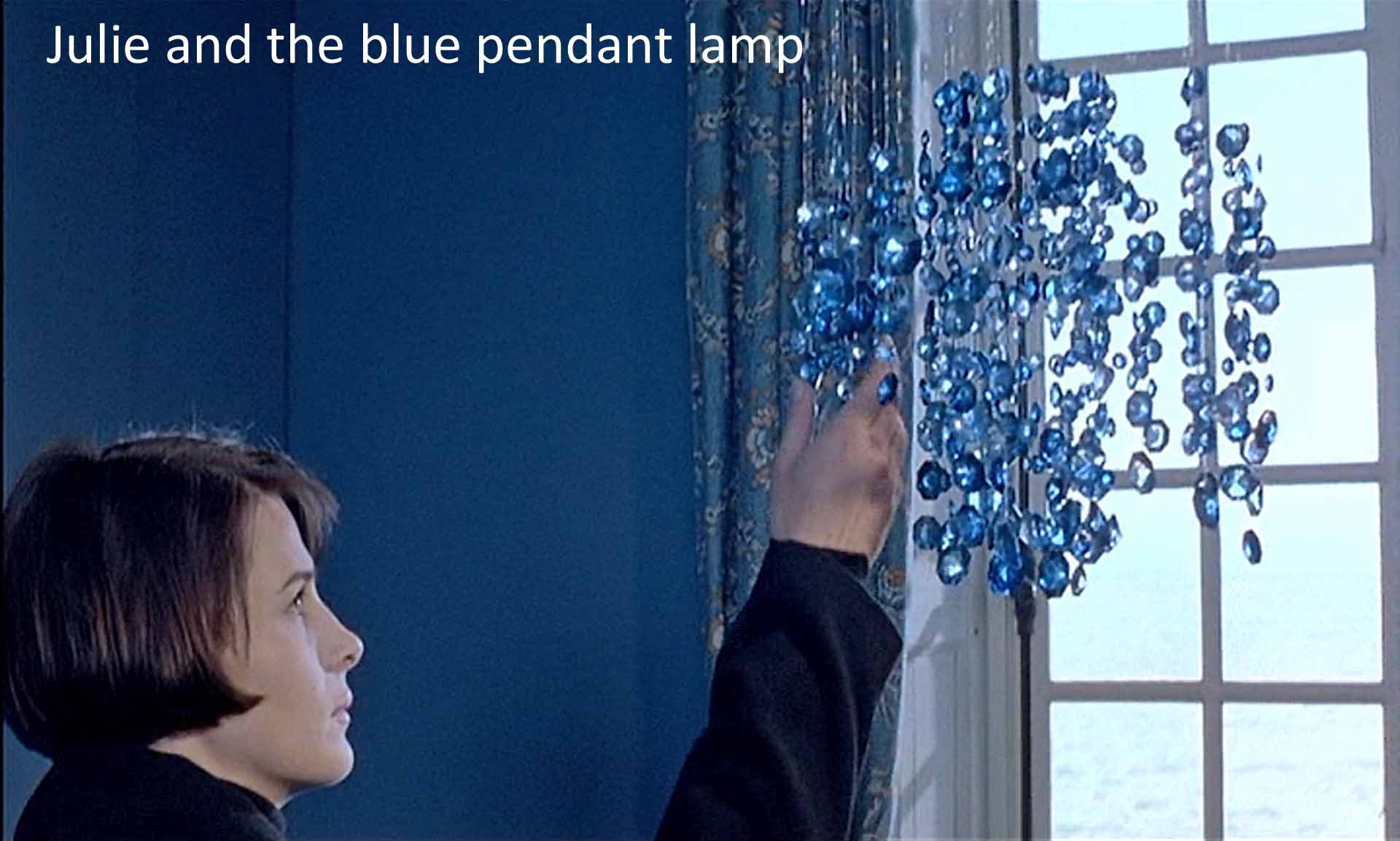

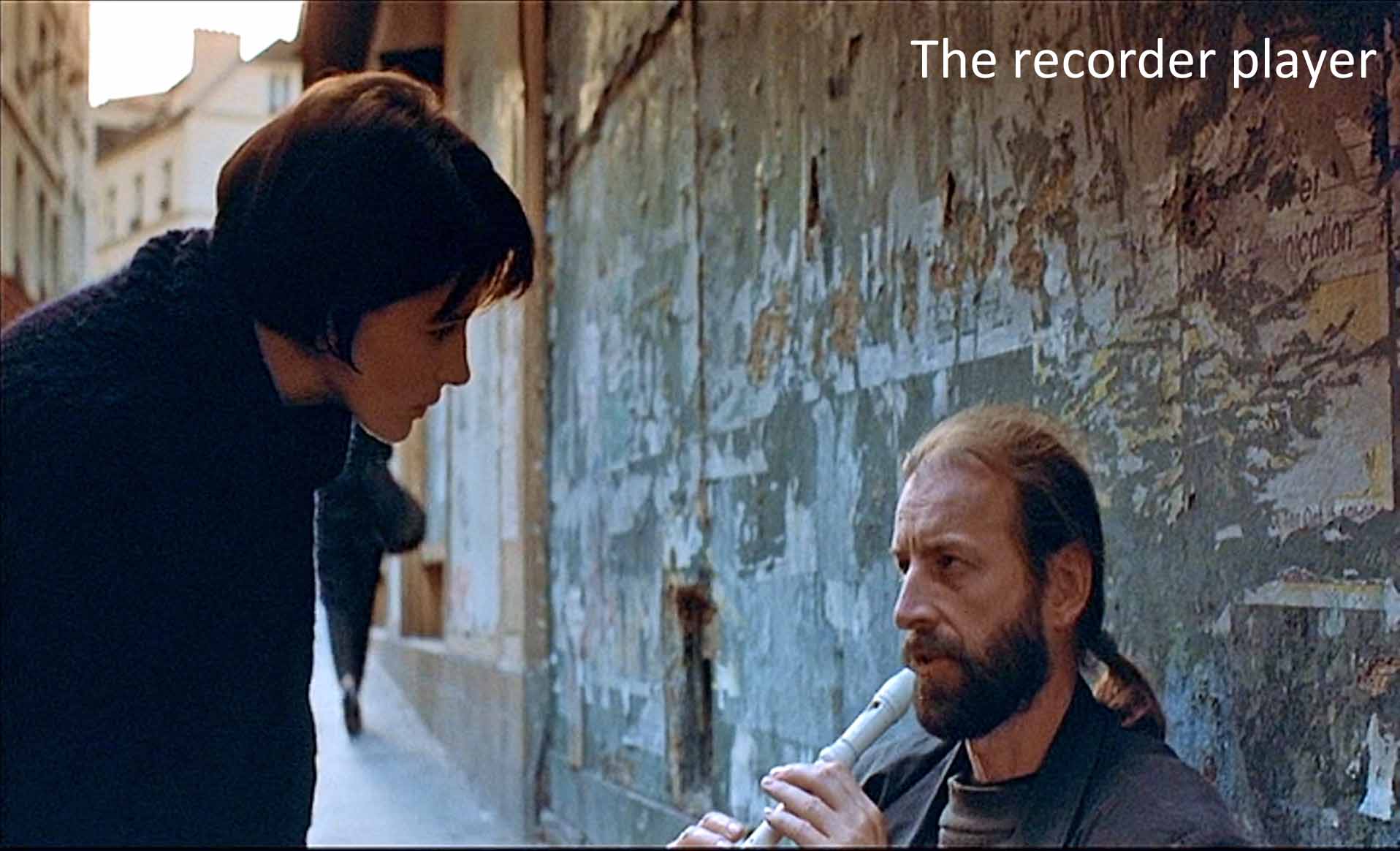

This film is thick with why’s. Some actions, of course, we can understand as motivated by the character and her situation: the rejection of Olivier; the destruction of the musical score; the retreat to Paris; the search for Sandrine; the final acceptance of a new family. But there are many incidental episodes not essential to the main action of loss and acceptance of loss. Why the blue pendant lamp? Why the street brawl? Why the old woman and the green recycle bin? Why the boy Antoine, first on the scene of the crash? Why the joke about the laxative? Why the sugar cube? Why the man playing a recorder? Why the swimming pool? Why include Julie’s mother and her odd taste in television programs, the elderly bungee jumper? Why Lucille and the strip joint? Why is it there that Julie learns of her husband’s infidelity? Why is Patrice’s mistress pregnant? And on and on. There are dozens of these incidentals. Why are they there?

It seems patronizing to say it, but remember—despite the powerful illusion that we are seeing a photographed reality—that everything we see in a movie was chosen. Kieślowski (plus his constant collaborator Krzysztof Piesiewic) wrote these inessential details into the script, he chose to film them, and he chose to include them in the final edit. Why? I answer by trying to see how they enlarge and enrich some over-arching concept that I infer or imagine governed Kieślowski’s choices. In Blue, I think that concept is connection.

Columbia professor Annette Insdorf takes the same approach in her superb commentary on the Criterion DVD of Blue and in her book on Kieślowski. It’s difficult to sort out where my own thoughts begin and where they derive from hers. She notes many, many of these details by which Kieślowski fleshes out his basic theme. I don’t know a better way to alert you to them than simply to list some of them as space permits.

Religion. Kieślowski was raised as a Roman Catholic. In an interview, however, he said he was not a believer and had not entered a church for forty years. Nevertheless he has, he says, a “personal and private” relationship with God. Kieślowski’s God is, it seems to me, a kind of superbeing through which each of us connects with, potentially, every other human, for example, through the pendant cross that ends up with Antoine. Connection—the “Unification of Europe.” That is what you see in this film and indeed the whole trilogy.

Music. The Concerto for the Unification of Europe was composed by Zbigniew Preisner before filming began for an earlier Kieślowski film, No End (1984). The piece names Kieślowski’s theme of connection and evokes it in the film. It was to be played by twelve orchestras in the capital cities of Europe and played only once. Kieślowski himself professes no interest in music. He and Preisner (who has done all the music for his films) have fun attributing various bits of Preisner’s music in this and other Kieślowski films to a Dutchman, Van Den Budenmeyer, a fictitious composer, whom they have fobbed off on unsuspecting researchers. In Blue, the music is sometimes diegetic, but mostly not. It comes in and floods Julie’s image (often accompanied by a blue filter), suggesting how she is overcome by the past trauma that she cannot escape.

Sounds. Annette Insdorf describes the sound track in general as “dense.” Kieślowski heightens sounds such as the click of the stick-and-ball game the boy Antoine plays or the sound of the tires and the car crash in the beginning or the sound of the garbage truck crushing Patrice’s manuscript or the noise of the street fight or the noise in the swimming pool or the squeaks of the baby mice . . . But throughout, he amplifies the sound, like the music, and that is one way he makes the movie reach into us and connect. Also, and this is characteristic of Kieślowski’s style, sound precedes sight. We hear the automobile tire, for example, before we see it.

The circular. Often the sounds accompany the many circular images: the tire in the opening shot, the incongruous beach ball at the scene of the crash, Antoine’s ball-and-stick, a spoon, a coffee cup, the window to the courtroom, the necklace with a cross, Sandrine’s pregnant belly, and on and on. The circularity perhaps suggests things coming back (the bungee jumper), the traumatic car crash, the return of the repressed (or, more properly, the suppressed).

The four blackouts. Four times, when the camera is on Julie, Kieślowski cuts to black. These are not the usual cuts to take us to a new scene; the focus comes back to where it was. Rather these are all situations in which Julie is flooded by the things she has tried to suppress. These are still other forms of circularity.

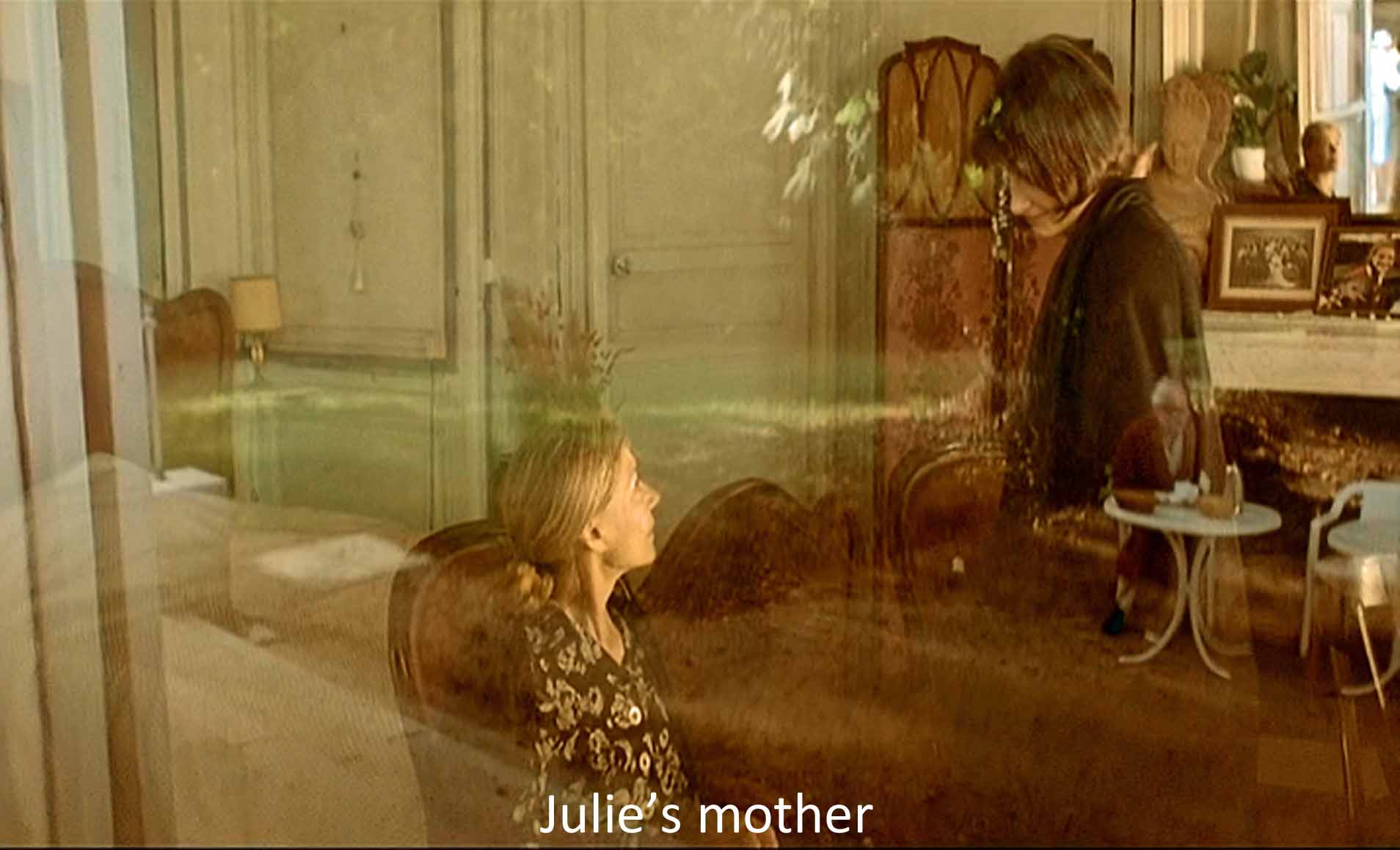

Julie’s mother. Motherhood comes up in several ways in Blue: the death of Anna, Julie’s daughter; the baby rats and Julie’s agony over them; the little girls at the pool; Sandrine's unborn baby: and, of course, Julie’s own mother. She is played by Emanuelle Riva, whose fame came with Hiroshima, Mon Amour (Resnais, 1959). This celebrated film also dealt with memory and forgetting, and Kieślowski’s casting Riva is a way of tying this film to that, as is Julie’s scraping her hand against a stone wall as the heroine of Hiroshima did.

Julie’s mother has become totally isolated behind glass, and we see her through reflections. She is in a hospital (as Julie was). She does not recognize her own daughter. She has lost her past (as Julie tries to do). She is glued to a television screen that yields her “the whole world.” But it is a world she watches and does not participate in. That is what Julie seeks for herself. The mother watches on her tv a tightrope walker and an old man doing a jump with a bungee cord. (Julie had seen a bungee jumper just before the televised funeral.) The old man bounces back, making the image circular: risk and survival, but Julie’s mother is inert—she is what Julie wants to be. Her state suggests the folly of Julie’s plan. It is our lot as humans to risk and hope we survive.

Glass. It separates us but lets us see one another, like Julie’s daughter looking out the rear window of the car or Julie seeing her mother behind glass or the hospital window Julie breaks. Blue has many windows, but many incidental other bits of glass, notably the blue glass pendant light that is Julie’s one link to her past (a link that connects her and Lucille). There are others, the glass television screens, the glass of the ultrasound screen, and then the final love scene with Julie pressed against glass. Glass offers both enclosing and opening. Glass both opens and denies ways to see and connect with others. The three television screens that we see open Julie to a world she tries to shut out.

Blue. It occurs in many ways in the film: the lollipop wrapper Anna holds out the car window; the folder with which Olivier retrieves Patrice’s personal papers; the blue lollipop; the blue pendant light; the swimming pool; Julie’s corrections on the score in blue ink . . . But it is never a symbol of liberté, freedom. Rather this is blue as in “the blues,” melancholy, cold, lonely—like Julie’s mind that blue sometimes floods.

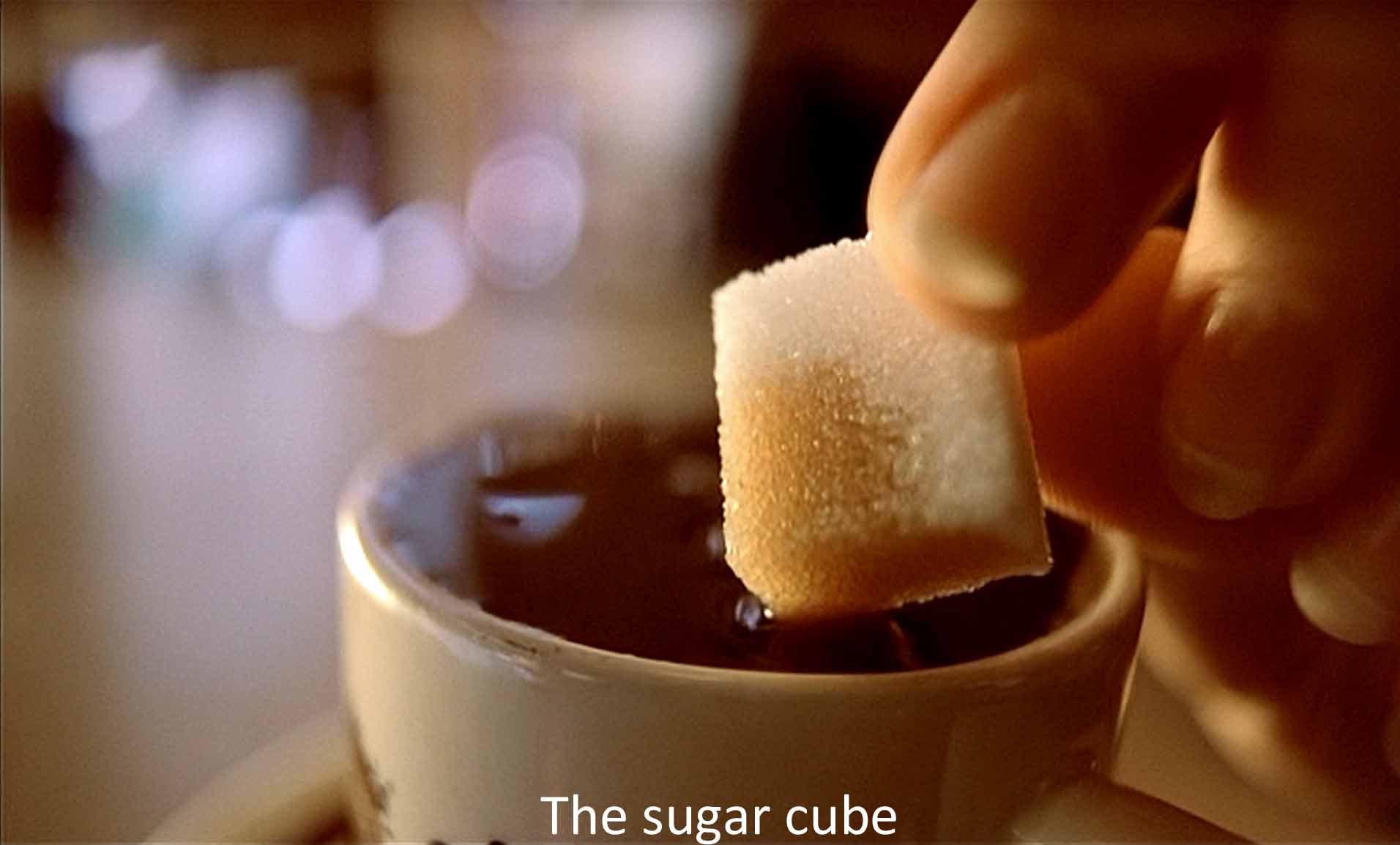

The sugar cube. One particular cutaway image has achieved a lot of attention thanks to Kieślowski’s twenty-minute video commentary on it. Julie holds a sugar cube touching her coffee so that the coffee soaks in. Then she drops the sugar in the coffee. Why devote a close-up to this? Why show it at all? In typical directorial fashion, Kieślowski talks about filming it, specifically finding a sugar cube that would take exactly five seconds to absorb the coffee, no more, no less. He explains the image as showing that Julie in her isolation focuses on little things. She is trying to limit her world to herself and her immediate environment.

OK, but I’ll suggest a different reading. I think the coffee soaking into the cube suggests the world—life—soaking into Julie despite her efforts. And when she drops the cube in the coffee, I think it presages her being herself absorbed and lost in the swirl of life. And I have the temerity to think the image is much more interesting understood that way.

It fits what Kieślowski says when he talks in that video about Julie’s dialogue with the street musician after the shot of the sugar cube. How can he be playing on his recorder her husband’s unpublished, indeed suppressed, music? It’s Kieślowski’s theme of the nearly supernatural connections between people. In the video, he says that the dialogue after the sugar cube shows that “different people at different parts of the world but at the same time think the same things. This theme is almost an obsession of mine, that people in different places and for different reasons think the same thing.”

That’s what the whole film and, ultimately, the whole trilogy is about, being caught up in the swirl of life, being connected in that almost supernatural way to other human beings: if I have not love, I am nothing.

In an interview given at Oxford University, Kieślowski spoke of his “deep-rooted conviction that if there is anything worthwhile doing for the sake of culture, then it is touching on subject matters and situations which link people, and not those that divide people. There are too many things in the world which divide people, such as religion, politics, history, and nationalism. If culture is capable of anything, then it is finding that which unites us all. And there are so many things which unite people. It doesn’t matter who you are or who I am, if your tooth aches or mine, it’s still the same pain. Feelings are what link people together, because the word ‘love’ has the same meaning for everybody. Or ‘fear,’ or ‘suffering’. We all fear the same way and the same things. And we all love in the same way. That’s why I tell about these things, because in all other things I immediately find division.”

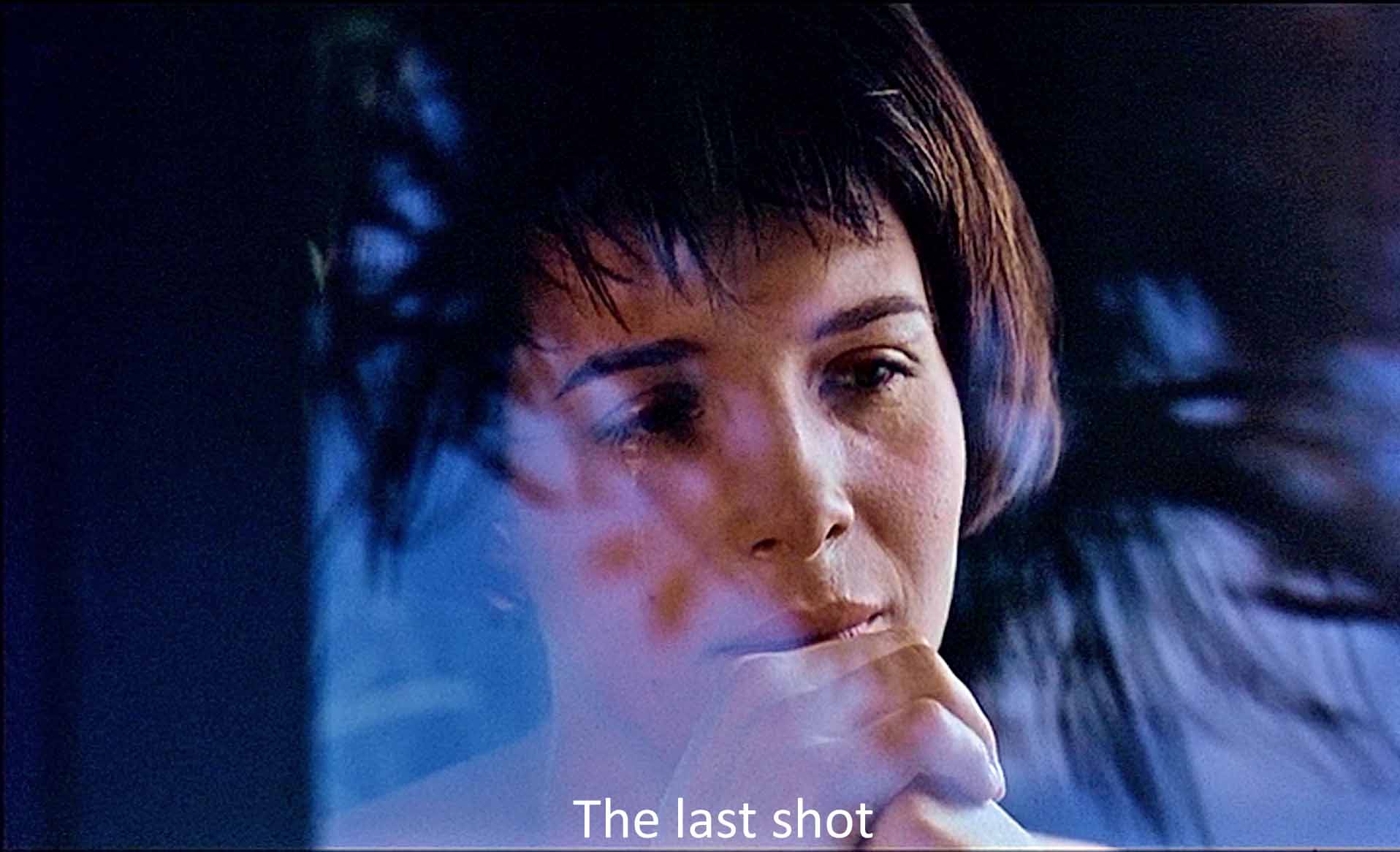

Thus, in the final sequence, Kieślowski gives us shots of those with whom Julie has finally connected: Olivier, Antoine, Julie’s mother, Lucille (in her strip joint), Sandrine looking at the ultrasound of her baby, and finally Julie herself, specifically her eye (that she would see films with). The sequence begins with Julie and circles back to her.

Is it a happy ending? Sort of. In that last long close-up of Julie’s face, in the final seconds, the corners of her mouth turn up. Binoche says she managed to smuggle that hint of a smile past Kieślowski. Whatever. The atheist Kieślowski finds redemption in our connections to other human beings, and Blue puts that redemption before our very eyes in a film that I think is, quite simply, magnificent.

Items I’ve referred to:

Abrahamson, Patrick (2 June 1995). "Kieślowski’s Many Colours". Oxford University Student. http://www.musicolog.com/kieslowski_manycolours.asp. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

Insdorf, Annette. Double Lives, Second Chances: The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieślowski. New York: Hyperion, 1999.

Insdorf, Annette. “On Blue.” Video included on Three Colors. Criterion Collection #587.