When I first saw this movie, I thought it was pretty straightforward. A dowdy daughter invites her mother, a famous and glamorous concert pianist, for an extended visit. They quarrel, the daughter accusing her mother of having been a neglectful parent. The mother leaves. The daughter regrets the quarrel and invites her again.

The mother, Charlotte (Ingrid Bergman), was The Artist, self-indulgent, totally focused on her career as a pianist and her playing (ignoring her daughter so as to practice six hours a day and go on tours). Her daughter Eva (Liv Ullmann) was the loving one, tending her husband, mourning Erik, her dead four-year-old, nurturing her disabled sister, and trying to get through to her narcissistic mother. If Charlotte represented Art, Eva represented Love, not erotic love, but mother-love.

Well, yes, but Eva torments her mother by bringing up all her failures as a parent—is that nurturing? In her next-to-last soliloquy, she blames herself for bringing up “an old hatred” and driving her mother away. “She can never forgive herself,” says her husband. Fair enough! Eva’s nurturing is ambivalent. Its underside is hatred.

But even this knot of human relations would be too simple for Ingmar Bergman. Autumn Sonata is more complicated than bad Charlotte and good Eva or even good-bad Eva. Rather, Bergman pits two character-types against each other. Eva is a mother-figure who needs to nurture others and therefore needs people to be dependent on her. Charlotte is the strong and energetic Artist, who uses others (like her agent or her lovers or her husband) to serve her art. That incompatibility between mother-love and art forms the core of our human failings and, so Bergman would say, our misery. And this has to do with Bergman's own psyche. He was intensely in love with his mother as a child, and intensely devoted to his art as an adult.

Ingmar Bergman created this film in Norway, during his furious, self-imposed exile from the arrogant tax authorities in Sweden. And it embodies his angriest meditation on the relation between Art (his filmmaking?) and Life (obligations, demanding people like the tax authorities). But I would trivialize this fine, fine movie by such a reading. Bergman would not be Bergman if he were not subtler than that.

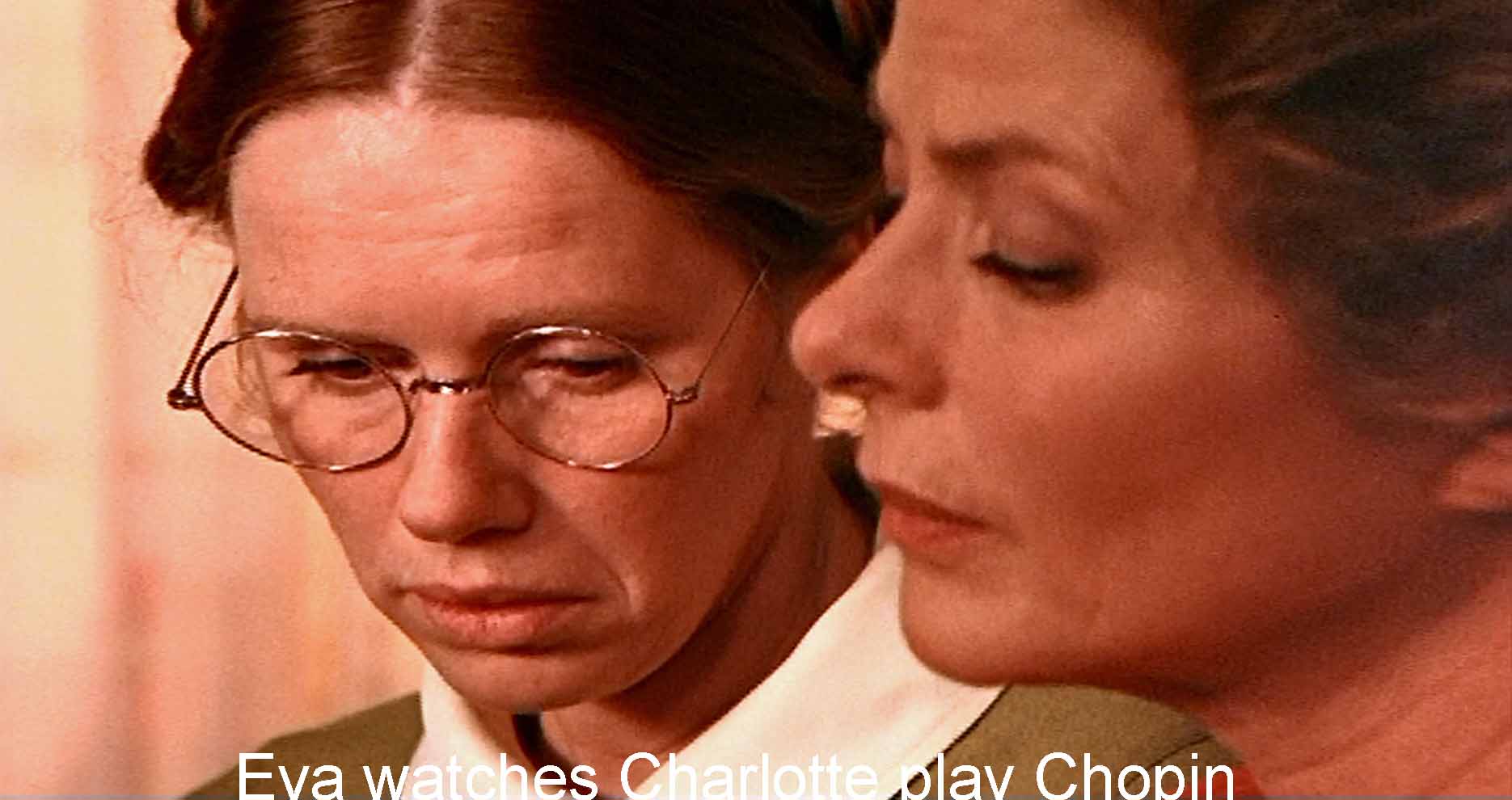

This is a film about a mother and a daughter, and the daughter's trying to contact the mother. There are two cruxes when each behaves cruelly to the other. One involves music, said in the film to bring out the human heart: Eva and Charlotte play a Chopin prelude. The other involves words, and surely, speech also brings out the human heart: Eva accuses her mother of terrible parenting; Charlotte defends herself. The mother uses music to hurt the daughter; the daughter uses words (and film—flashbacks) to hurt the mother. The whole film rests on dialogue, but then there are those powerful close-ups of faces (Bergman’s art). Music and film represent Art, and words represent human love (or the failure of love), and the two spheres are, in Bergman’s work, utterly separate and antagonistic. This is a film about words and music and how the words don’t always go with the music.

Although Bergman himself describes this film as “a story in three acts,”; Bergman expert Peter Cowie suggests that Bergman structured this film, as its title suggests, in the four movements of a classical sonata. That makes sense to me, and as I divide the film, the first movement introduces its major theme, the mother-daughter, parent-child relationship—call it Love or Life with a capital L.

Eva is married to Viktor (Halvar Björk), a quiet older clergyman who is anything but victorious. They had had a child, Erik, but he drowned. Now Eva has moved her younger sister Helena (Lena Nyman), severely disabled by cerebral palsy, into their house, and Eva is pleasing and fulfilling herself by taking care of Helena.

The opening scene tells us what this film is about: humans contacting humans. It also establishes one of the recurring concerns of the film, one of the ways people contact each other, words (and, as we shall see, their failure). The action begins with Eva sending a letter to her mother, Charlotte, inviting her for an extended stay. also, in the opening scene, Viktor establishes himself as what he will be throughout the film and especially in the opening and closing scenes, a sympathetic, understanding audience—us. He watches his wife without her knowing—as we watch her, and he explains what she is doing, writing her mother. And he smiles ironically, as if he knew how this was going to work out.

Second scene: Charlotte drives up in her white Mercedes. She is a famous concert pianist, but delighted at the prospect of a restful stay with her nurturing daughter. She gets enthusiastic hugs from Eva (another form of contact, touch), and the two look happy indeed. Charlotte’s face falls, however, when she learns that Helena is there, but she tries with good grace to hold her (and to understand what she says, but only Eva can interpret her tortured speech—words again).

In the second movement, we get the other major theme, Art with a capital A. After a chummy family dinner, Charlotte gets Eva to play a Chopin prelude, which she does—awkwardly. Eva then insists that Charlotte play it. She does, but she cannot resist becoming the consummate artist; she cannot not interpret the prelude brilliantly and so humiliate Eva. (Bergman's fourth wife, a concert pianist, was doing the playing.) Another theme: Art with a capital A. (And fittingly Ingrid Bergman’s acting becomes quite amazing: with only her face, she expresses affection for her daughter, a bit of contempt for her playing, discomfort at her contempt, being moved by the prelude, and wanting to play it herself, the right way—or am I reading in?) Art is the ultimate way people can express their deepest feelings and contact—touch—one another (as Chopin and Charlotte do and Eva does not). But this is not real touch, real love.

The third movement turns back to the contrasting theme, words or Love or Life, specifically, how Charlotte, as a mother, failed her daughters. After an affectionate chat with Eva, Charlotte gets ready for a cozy night’s sleep, settling down with a trashy novel by a former lover—more words. (The paperback has Bergman’s picture on it!—an inside joke that links Bergman’s filmmaking to words.) But Charlotte has a nightmare: a hand touches her hand and cheek; apparently it is Lena’s hand. Frightened, she can’t get back to sleep and goes downstairs. Eva joins her, and they begin talking—words.

Eva now accuses Charlotte of being a dreadful, uncaring mother, as she apparently was. Bergman gives us flashbacks of Eva’s life as a little girl. (Linn Ullmann, Bergman’s and Ullmann’s daughter plays the part.) The flashbacks show us Charlotte ignoring her little girl to practice six hours a day, Charlotte leaving for long tours, Charlotte showily showering affection on her return. (Interestingly, in this movie of intense close-ups of faces, Bergman uses long and medium shots for these pictures of the past, perhaps to emphasize the coldness they describe, perhaps to show the distance from the present.) Eventually, Eva furiously accuses her mother of ruining her life, destroying her self-esteem as a teenager, ending an early affair, demanding an abortion, and meddling in her current marriage. Deprived of concertizing by her health, Charlotte apparently turned all her energy toward re-making her daughter.

After all this, Charlotte lies on the floor to ease her back pain in the same baby-pose as Helena, suggesting how Eva needs her mother to need her so that she can be her nurturing self. Charlotte says, “Sometimes, when I lie awake at night, I wonder whether I’ve lived at all.” “Only through music did I have a chance to show my feelings.” The scene ends with Helena pulling herself out of bed and futilely screaming, “Mama, come!” For all three of these women, mothering failed.

It’s a cruel, harrowing scene with Eva tormenting Charlotte and Charlotte trying to justify herself. It seemed to me to reveal the anger under Eva’s seemingly devoted nurturing. I could not help remembering the wry opening of Philip Larkin’s famous lyric:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

I see Eva and Charlotte (and Viktor) each working out what I’ve described in my psychological writings as an identity theme. By that I mean a style of being and doing that derives from early childhood experiences and relationships with our parents, but mostly mother. It is a personal style inscribed, I believe, in our brains before we have language to describe it. I think it determines not so much what we do, although some of that, but how we do it. It is an individual style that permeates everything we do or say. In this film, Charlotte’s identity theme is her art—her performance in concerts and pretending in life. (I’ve argued that the creativity of the artist comes about when a medium, here the piano, becomes meshed in an individual’s identity theme.) Charlotte is happy and energetic and, she says, giving of herself when she performs on the piano. She is self-centered and self-indulgent and trivial when she is not performing.

Eva’s identity theme is nurturing. It is what she feels compelled to do, what fulfills her, and what she feels happy doing; it is how she defines her marriage, her mourning of her dead child, and her life. When she can’t nurture, she turns nasty, as in this cruel scene with Charlotte when nurturing turns into its opposite.

And even Victor demonstrates an identity theme: he watches his wife without her knowing; he interprets the events. He is a sympathetic, understanding audience. He is also one of Bergman’s ministers whose faith is shaky. As he says, “Unlike you [Charlotte] and Eva, I am diffuse and uncertain.”; The perfect audience—he has no axe to grind.

In the fourth movement, Charlotte has left and she and Eva put their splintered lives back together, Eva nurturing, Charlotte performing. On a train to Paris, Charlotte nuzzles (touch) her agent Paul (Gunnar Björnstrand) and justifies herself, concluding that she has always given freely of herself in her art. Yet she ends the conversation by looking doubtfully at her reflection in the train window.

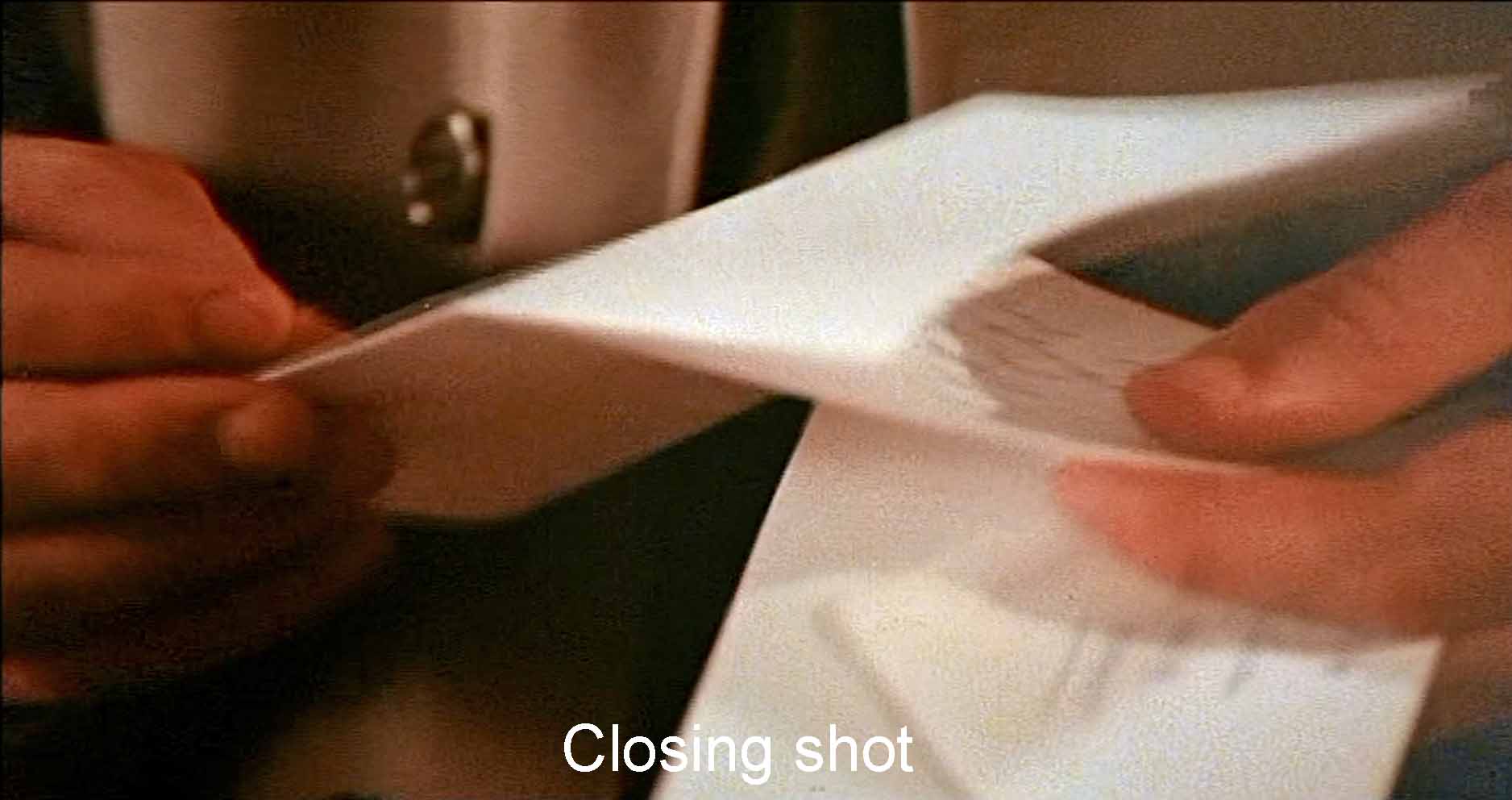

Simultaneously, Eva, in front of Erik’s grave, contemplates suicide but also says: “There is a kind of mercy after all. I mean the enormous opportunity of getting to take care of each other, to help each other, to show affection.” “Poor little mama, she says, casting Charlotte, tough Charlotte, in the role of one of her dependents. Now the nurturing Eva, she writes a conciliatory letter to her mother, which Charlotte apparently reads (despite Eva’s claim that she might not). In the final shot (out of sequence), Viktor folds that letter up for mailing (touch, this time a hand touching words).

Besides music and words and Art and Life, other thematic threads run through this film about human contact.

Love In a way, this whole film is about love and attempts at love and the failure of love. The characters talk and talk about love, notably when Viktor tells Charlotte that Eva has told him she is incapable of love (presumably, because she had no mother-love as a child). “I was quite ignorant of everything to do with love,”; presumably because her parents never touched her.

Death Death frames this film. It begins by showing us the death of Leonardo (this is a film about art!), Charlotte’s lover or husband of eighteen years. It ends with Eva thinking about suicide as she stands in front of her dead son’s grave. Throughout, everything about Eva is rendered in an autumnal palette, brown, yellow, olive green. Charlotte expresses herself in a white Mercedes and a bright red gown (and red, Bergman has said, is the color of the human soul).

Touch Again and again the characters speak of touch or, more often, not touching. During the quarrel, Charlotte sadly notes, “I can’t recall my parents ever having touched me." There are hugs when Charlotte arrives, and she forces herself to embrace Helena. Then she has a nightmare: Helena strokes her cheek. Much later, at Erik’s grave, Eva will speak to her dead son, “Are you stroking my cheek? Are you with me now?" Viktor wants to tenderly touch Eva as he walks past her at the dining room table but thinks better of it. In the final shot, Viktor’s hands touch Eva’s words as he folds up her conciliatory letter to her mother. Then, too, we see Charlotte’s hands touching the piano keys. Touch involves both Life and Art. By touch, humans could bridge the basic incompatibility of human beings, but, in Bergman’s world, they probably don’t.

Time. It is omnipresent in this film, and not just in Bergman’s favorite shots of a clock face. The relation between Eva and Charlotte involves the influence of the past on the present, of parenting and childhood on the adult. Eva and Viktor cannot stop thinking of their dead son—even giving reluctant Charlotte a slide show of him. Bergman uses a peculiar style of cutting in this film. We go from one scene to the next without knowing how much time has elapsed or why we are going where we go. The film delves into past time but leaves us with hope for a better future between Eva and Charlotte. And music—music is an art made of time itself.

Autumn Sonata—it is beautifully complex, as complex as the musical form that gives it its name. I see this and other films of what I think of as Bergman’s fourth phase as perilously close to a soap opera (for more on phases, click here). Tempting as it might be to read the film as purely a drama between an unloving mother and a resentful daughter, it is so much more than that. As always with Ingmar Bergman.